In recent years, the quality of law-making in Poland has significantly deteriorated. Practices such as ignoring procedures, bypassing public consultations, using the deputies’ initiative route for government projects, and last-minute insertions in the final stage of the legislative process have been a constant element of the political landscape.

These practices served for the rapid implementation of the ruling party’s will at the expense of the quality and transparency of legislation. While these practices were not new, they have particularly become widespread since 2015, a trend also confirmed by empirical data. This led to a further erosion of citizens’ trust in the state—and worse, it undermined trust in democratic processes.

The last eight years have predominantly seen a departure from creating evidence-based public policy-making—both in terms of formal legislative activity and soft practices. One of the new government’s first decisions was to abandon the creation of assumptions in the draft acts and the introduction of the possibility of skipping the stage of public consultations and collecting opinions from other state bodies. This allowed for “hiding” government draft acts from the public and presenting them at a very late stage of the legislative process, shortly before sending them to parliament.

The last two parliamentary terms also saw an increase in presenting government proposals as projects endorsed by a group of MPs from the ruling party—allowing bypassing of the government’s legislative process requirements. Such practice not only blurred the line between the government and the ruling party but also reinforced the belief in the possibility of freely using state resources to implement a political agenda. After all, what difference does it make whether ministry officials write a project for the minister or his colleagues from the parliament—as they all represent the same coalition… It is noteworthy, for example, that almost all draft acts concerning the judiciary, including the project on the National Council of the Judiciary, were submitted by groups of MPs.

Another observed phenomenon was the use of the so-called MPs’ insertions and the submission of key amendments unrelated to the subject of the drafts in the final stages of the legislative work. As once stated by the legal (back then) Constitutional Tribunal – the closer to the enactment of a law, the narrower the scope of amendments should be.

However, the creative work of MPs could, at the last moment, completely change the implications of the draft or introduce elements entirely unrelated to it—in both cases, it raised doubts about whether such law truly underwent the full three readings in the parliament as required by the Constitution. In the last Sejm’s term, there was a discussion about an amendment submitted by Adam Gawęda, an MP from the ruling party. At a meeting of the combined Public Finance Committee and Economy and Development Committee, where works on the law on export insurance were underway, he submitted an amendment unrelated to the subject of the draft – tightening the pharmaceutical law.

Politicians also abused the trust in draft acts presented as citizens’ initiatives, which in reality were endorsed by the ruling party. This practice aimed to lend controversial projects a “civic” and manipulate public opinion. It is worth mentioning the flagship proposals of Sovereign (formerly Solidary) Poland, such as the bill “in defense of Christians” or “in defense of forests“, aggressively promoted by politicians of this party spread throughout the ministries.

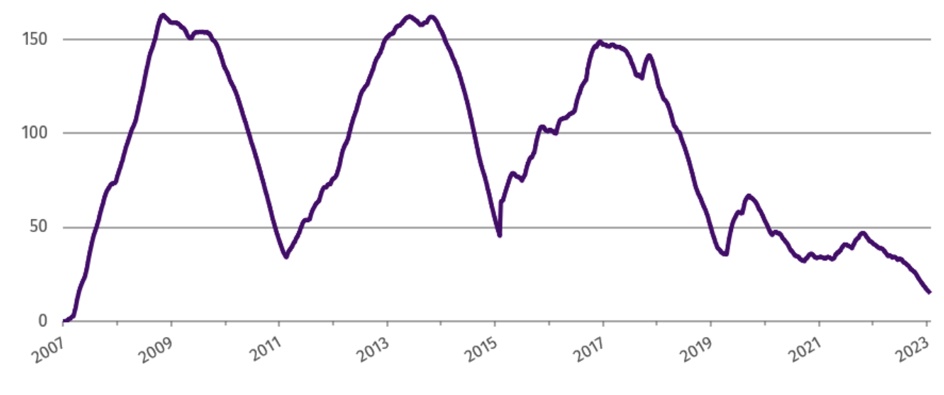

As a consequence of employing these practices, especially in the last parliamentary term (2019–2023), the average time for enacting laws was radically shortened. As we calculated, compared to previous terms, this period has almost tripled, achieving less than 50 days. These actions adversely affected the quality of the laws, increasing the risk of legislative errors, unintended consequences, and above all, negatively impacting the legitimacy of such enacted laws.

Graph 1. The average time between the first and third readings of an act in the Sejm from the sixth to the ninth term (in days) (12-month moving average). Own calculations based on parliamentary data.

Regarding the judiciary, it is worth noting that key projects concerning the judiciary were often based on false data. In the case of changes to the Constitutional Tribunal, the recommendations that formed the basis of the new law were developed in 2016 by a workgroup of lawyers assembled by the Speaker of the Sejm.

The result of the group’s work was an unreliable report, providing the ruling party with arguments to “reform” the Tribunal. The issue of changes in the National Council of the Judiciary was approached more carefully. For the first draft act (the only one prepared by the government), even an impact assessment was prepared, in which ministry specialists expressed sincere concerns about the effects of changes in the NCJ regarding the economic sphere. As a result, the project was withdrawn, and the author of the assessment faced professional consequences.

The recent government also caused a weakening of the staff responsible for legislation and the assessment of public policies. Bodies such as the Bureau of Research of the Sejm and the Government Legislation Centre were either led by members of the ruling party or served as a springboard to better positions for those who supported with their authority the unlawful decisions of the parliamentary majority. On one hand, this adversely affected the reliability of opinions prepared for draft acts, and on the other, it allowed the former parliamentary majority to maintain the appearance of legality and claim that these projects were evaluated objectively.

Almost half of the third decade of the 21st century is the best time to finally correct the process of creation of public policies and the legislative process—thereby restoring trust that the state operates lawfully, does not deceive citizens, and cooperates with them to solve their problems. Strengthening the role of social consultations, increasing transparency, and further digitalization of procedures are only part of the solution. We need ambitious, innovative, and perhaps unconventional solutions. If we want to become an exporter of judiciary reforms, why not increase the volume of this export with good law-making practices?