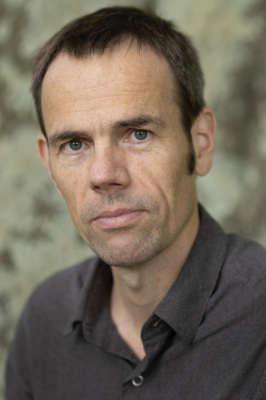

In this episode of the Liberal Europe Podcast, Leszek Jażdżewski (Fundacja Liberté!) welcomes Luuk van Middelaar, a political theorist and historian, a Professor of EU law at Leiden University, a political commentator for NRC Handelsblad, and the author of the prizewinning book The Passage to Europe. They talk about European resilience and solidarity, how the EU has responded to the COVID-19 crisis, and the importance of European public.

Leszek Jażdżewski (LJ): What has the European Union learnt about itself from the experience of the COVID-19 pandemic?

Luuk van Middelaar (LvM): The key lesson that the EU has learned happened at the time of great vulnerability and divisions among member states and a lack of solidarity. Right at the start of the COVID-19 outbreak in February and early March 2020, when EU countries scrambled for medical materials, everybody was trying to save their own citizens while patients were gasping for oxygen. It all started very bitterly. But there was also a very surprising turnaround.

In a matter of several months, European leaders made two very far-reaching decisions – one on the medical and another on the economic front. In terms of the former, the EU Commission was given mandate to purchase COVID-19 vaccines for EU citizens. Those days, it was all very bleak. People were afraid as they faced great uncertainty. The vaccine was viewed as the only hope – the light at the end of the tunnel. For national leaders to outsource this task of this life-saving vaccine to the European Commission was a big decision, which they made in June 2020. They realized – and German Chancellor Angela Merkel was very clear on this – that it was very important to do this together as a union, because otherwise the divisions and working only for oneself would repeat themselves.

The other far-reaching and almost revolutionary decision was made in the summer of 2020, when the EU leaders decided on the coronavirus recovery fund with EUR 50 bn to be distributed among EU governments for the societies that had been hit by the COVID-19 crisis. In a way, the EU was crossing a number of red lines. Luckily, in the face of the crisis, the EU has shown an unexpected resilience. This confirms what we have seen in previous crises (the Euro crisis is probably the best example) that when pushed, there is a kind of unexpected energy and resilience that can be mobilized for the EU to pull through.

It was a big lesson. What also strikes me as very important in terms of the COVID-19 crisis is the role the public opinion played in the political decision making. This is a rather new phenomenon. A public call for action came early on from Italy, which was severely hit by the pandemic, and Spain to mobilize the European Union – even though technically and formally speaking the EU as such does not have competence in the field of public health. The public insisted that this be changed. This call for political action drove decision making – a bottom-up approach that had not happened on such a scale before (including during the Euro crisis).

The reason for this strategy being successful was that this call for action resonated very well with, for instance, Angela Merkel, who realized that Germany could not afford to be the Ebenezer Scrooge of this crisis – of a story focusing only on discipline and everybody doing their own homework. Germany had to step in to provide solidarity – with Italy and Spain in particular.

LJ: Did this ‘turnaround’ happen due to the fact that COVID-19 acted as a ‘deus ex machina’? Or was it a lesson learned from the Euro crisis, during which Greece almost went bankrupt and was forced to leave the eurozone? What prompted this response of the European Union to be much timelier and more efficient?

LvM: The main reason for the response was faster and more direct this time around was the nature of the crisis, it being a public health crisis. Hundreds of people were dying in hospitals and nursing homes. The sheer magnitude of human suffering had made the argument of solidarity so much stronger. In contrast, something like the Euro crisis – even though it was really serious and concerned people’s wages – was more abstract. This is why during the COVID-19 crisis there was this powerful drive for empathy and solidarity.

What made this situation politically translatable (for the German Chancellor in particular) was the fact that this was a crisis that had affected everyone symmetrically. It was really the fault of Italy for being ill-prepared, when it happened to be the hotbed of the virus coming from China. These two elements were the strongest. These were, of course, backed up by expert opinions on the mistakes made during the Euro crisis, when the discourse of discipline, austerity, and severity was much stronger.

Clearly, this development points to certain changes in German public and expert opinion in the past ten years. It became the primary impulse for going to the rescue of people who were dying. This is what basically made this crisis so special for somebody like Angela Merkel. On behalf of Germany, she made a decision to engage in the corona dance – and the public opinion supported her in a manner of days, which in itself was very surprising. Even somebody like Wolfgang Schäuble (the finance minister during much of the Euro crisis who was a kind of a ‘boogeyman’ in a large part of the southern Europe, including Greece) quickly said that it was perfectly normal to give grants rather than loans to people who were struck by the COVID-19 crisis, because otherwise it would be like giving ‘stones instead of bread’ – in a sense that it would only increase the debt. So, there was a very strong emotional undercurrent in these decision, which I found very striking.

LJ: Counting from 2008, we had only two brief years that were not abound in crises. Should we adjust to this new reality? Should ‘crises’ still be referred as such? Or do we live in a new reality?

LvM: It is a new world. Since 2008, which I would consider to be the starting point of this process, even though it may seem somewhat arbitrary – we are experiencing the acceleration of history. 2008 was the year of Lehman brothers and the ‘almost’ collapse of the financial system, the ‘August war’ between Russia and Georgia, and the time when China emerged as a global power. Since then, Europe has experienced a series of shocks of various nature – economically, geopolitically, as well as issues related to migration and borders. There seems to be no end in sight.

There, of course, is the question of semantics – when do we stop talking about ‘crises’. However, what is important is that as Europeans we have to be ready for the road ahead, knowing that we will be struck by further acts of aggression and uncertainty – be it from the side of China, Russia, or, who knows, maybe the United States in a re-enactment of the Trump administration. We have to move away from a kind of naivety in our outlook as Europeans, when we though that we could ban the language of power, interests, and strategy, because – as the EU in particular- we were going to build a new world free of all these elements. This was a big mistake.

What we are seeing now is that these naïve views are being completely undercut. The war in Ukraine has been the most dramatic and convincing example that we need to catch up with this new world and get ready for it. What is interesting is that even in the responses to this new crisis we can see some of the lessons learned from previous episodes are being taken on board, and some of the EU’s responses to the war in Ukraine came about more swiftly and convincingly because of these past experiences of vulnerability.

For example, there was a rather radical decision of the EU to jointly purchase the vaccine to get the COVID-19 outbreak under control. During this new crises, national leaders (knowing they will be faced with shortages of energy, and gas in particular) came up with the idea to ask the European Commission to help collectively purchase gas for the countries who are interested in it. When this strategy was employed for the first time during the COVID-19 crisis, it took a lot of persuasion and time for it to come about as a collective decision. Now, it is already considered a part of the ‘treasure trove’ of the common European experiences, which we can use.

Recently, the head of the German Energy Agency commented on how to secure energy for winter and how to make it possible if we will, basically, need to ask people to turn the temperature down by a few degrees without having the police knocking on every door. The argument he made was interesting – he said that individuals will take their part of responsibility in contributing to a collective goal of either becoming less dependent on Russian gas (in the current case), or collectively coming on top of the COVID-19 outbreak (in the previous crisis).

LJ: How would you describe the response of the European leaders to the war in Ukraine so far? Do you think that the much-talked-about strategic autonomy did not materialize in this case?

LvM: The response has been fairly united, given very different starting points as well as different levels of exposure and interdependence with Russia. If we take the United Kingdom on the one hand, and Germany on the other hand, with France being somewhat in the middle between the two and try to map where they are in terms of their dependence on the Russian gas, the UK (together with the Baltic states, and Poland, to some extent) would be very supportive of Ukraine. Meanwhile, the German dependency on the Russian gas has been exposed. France has tried to play the role of a diplomatic actor, with President Macron believing until some point that the diplomatic could be found.

Italy was a very surprising actor, under the leadership of PM Mario Draghi. The country’s dependence on the Russian gas was similar to that of Germany. However, very early on, the prime minister took a hardline stance in regard to sanctions and on becoming independent of the Russian gas. Now, of course, Italy is ahead of its September election, and we shall see what happens then.

All in all, by seeing how these various stances, interests, and values come together in the EU decision making, we may come at a conclusion that the level of support for Ukraine has been unprecedented. It culminated in the decision to grant Ukraine a candidate status to the EU at the June 2022 European Summit. This would never have happened in January of the same year, before the war. The impulse of the war and a beleaguered country knocking at the EU door made the European leaders decide that it was time to open that door and to offer that prospect.

Even though, it may take a very long time for the actual membership to be achieved by Ukraine, as an act, it is not just a symbolic one, because there is a true promise that cannot be backtracked. As such, it was very well played, in a way.

When it comes to the ‘battle of narratives’ between solidarity and discipline, which was evident both in the Euro crisis and the COVID-19 crisis, in the case of the dramatic story of the Russian war in Ukraine it is safe to say that Ukraine and President Volodymyr Zelenskyy have masterfully won the battle of narratives in Europe. Some minorities aside (especially on the extreme or nationalist right – including in Hungary, I am afraid to say as well), overall, the story which is shared by the media and the public opinion is of heartfelt solidarity with Ukraine.

LJ: Can the European Union become a geopolitical player given the recent challenges? Will the ‘politics of doom’ painted by some political actors and used to frighten people change? Will the public opinion force their leaders to think in a more geopolitical manner?

LvM: The short answer is yes. The European public opinions are much more aware of vulnerable our societies are. We have experienced it with face masks and now, with gas and energy. There is much more political space for leaders to rally and persuade the public opinion, parliaments, etc., to take action before it is too late. And this is very important, because taking action before we find ourselves facing the abyss.

This ‘politics of doom’ have happened many a time in the recent past. Things have gone so far as to face an existential threat – for instance, in the case of the financial problems in Greece. Such an approach is risky, because it results in, eventually, being too late – when there is no longer enough space in the public opinion and, therefore, more political space, to look ahead and be more strategic about such issues as industrial policy (in the COVID-19 crisis) or energy (as is the case right now).

To survive and prosper in a world where we can no longer rely on global chains, we have to organize ourselves as a bloc – and, in the case of Europeans, as a union – to be able to weather the storm ahead. I personally hope that we, as Europeans, can act more strategically and that we are no longer systematically outwitted (be it by the Russians, the Chinese, or Trumpian Americans).

Find out more about the guest: www.luukvanmiddelaar.eu

The podcast was recorded on August 18, 2022.

This podcast is produced by the European Liberal Forum in collaboration with Movimento Liberal Social and Fundacja Liberté!, with the financial support of the European Parliament. Neither the European Parliament nor the European Liberal Forum are responsible for the content or for any use that be made of it.