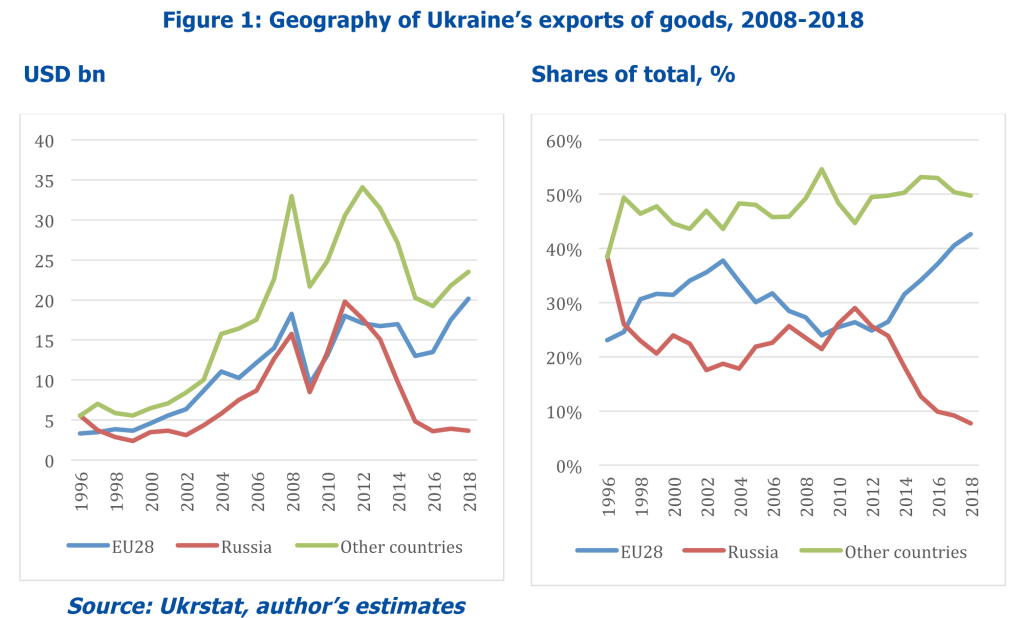

Ukraine’s dependence on the market for exports to Russia has been declining drastically since 2011 [See: Figure 1]. Until then Ukraine’s exports to Russia, the EU, and the rest of the world had been following similar paths.

Since then exports to Russia got onto its own downward trajectory due to Russian aggression against Ukraine. New sanctions by Russia towards imports for Ukraine introduced in late 2018 and 2019 are now set to reduce these export flows even further.

The new set of Russian sanctions applied in the implementation of President Vladimir Putin’s framework Decree #592 in October 2018 is multifaceted.

In November 2018, the Russian government imposed asset and capital restrictions on selected Ukrainian citizens and legal entities.

In December 2018, a ban on imports of over 200 product categories from Ukraine was introduced, and another ban for about 140 products followed in April 2019.

The list of affected products is quite broad, including agriculture and food products like wheat, sugar confectionery, and wine, as well as industrial machines and equipment like generators and dielectric transformers, base metals like tubes and pipes, apparel and shoes, wallpaper, and many others.

Altogether, the value of Ukraine’s exports of the banned products was USD 569 m in 2018 or 1.2% of Ukraine’s total exports. The expected losses are not significant in aggregate terms, although quite substantial for exports to Russia (16%).

The impact on the Ukrainian economy would have been much worse in earlier years (for example, in 2013, the value of the affected products was five times larger).

However, since then, the reorientation of Ukrainian exports to other world markets, especially the EU, has been profound: About 60% of products subject to the ban were not exported to Russia at all in 2018.

There are exporters for whom the bans are very painful, namely those who have been predominantly supplying the Russian market, and a quick reorientation for them looks very questionable.

The value of banned exports featuring predominantly exported to Russia (over two-thirds) in 2018 is USD 184 m, or one-third of the total.

The list of the products with the lowest reorientation potential includes primarily machines like DC motors and generators, liquid dielectric transformers, exports of which have been traditionally more oriented on the Russian market.

The exports of the remaining USD 385 m, already to some extent diversified, are likely to recover quite quickly through the reorientation to other markets, although potentially with lower profitability. On June 21, 2019, the Russian government issued a Resolution partly reversing its sanctions. The ban was temporarily released for eight products amounting to USD 117 m (or almost 21% of the banned products).

However, this temporary measure seems more like a response to the domestic lobbying efforts rather than a change in policy. For one type of liquid dielectric transformers, the “window of opportunity” for exports was opened for ten days only, from June 21 until July 1. For most products, the ban is relaxed for three or six months, and only exports of specific tubes remain unrestricted until October 2021.

Overall, the decline in the importance of the Russian market for Ukrainian exports is now of radical proportions. While in 2018 the share of exports to Russia had fallen to 8% (compared to 29% in 2011), in 2019 there is a further deep fall underway, with a 16% drop in the value of these exports compared to a year earlier.

The counterpart is primarily seen in the growth of exports to the EU, which has risen from a 26% share in 2011 to 42% in 2018, and more in 2019.

At the same time, exports to the rest of the world have been steadily increasing trend share of Ukrainian exports, rising from 40% in 1996 of the total to 50% in 2018.

In the next few years, there could be a recovery of exports to Russia, the sanctions might be removed. However, even if this happens, a profound lesson for Ukraine’s economic future has been learned.

Politically, Russia’s trade policy is seen to be damagingly erratic and protectionist, whereas the stability of the EU’s trade policy under the DCFTA with Ukraine is solidly entrenched (both legally and politicall)y.

In addition, trade in the rest of the world includes so many trade partners that this diversity is a further valuable insurance. For export-oriented businesses looking for strategic stability in export market prospects as a basis for investment decisions, the main parameters are thus clear.

The publication was prepared within the framework of the CEPS-led 3DCFTAs project, enabled by financial support from Sweden. Views expressed in this publication are attributable only to the authors, and may not be attributed to either the partner organizations of the project or the institutions to which they may be attached, or the Government of Sweden