High inflation has long been the most serious macroeconomic challenge our country has faced in recent years. It was far from being only economists who identified deep price instability as a major problem, as the wider public viewed the extraordinary rise in most prices in the economy with equal reluctance.

This bitter experience has thus reaffirmed a fact well known to economics long before that high inflation and the distortions in relative prices of which it is the perpetrator manifest not just economic but social and political costs of a wide range. If we are to avoid these unpleasant pitfalls in the future, it is not only desirable but downright necessary to understand what forces have been driving the inflationary wave to such high levels for such a long period.

In this respect, it would be useful to mention first the confusion that is not infrequently encountered, which arises from the failure to distinguish correctly between two different phenomena, namely changes in relative prices and changes in the general price level. The relative price is the price of one good in terms of another good. In any functioning economy, there must necessarily be continuous changes in relative prices, since the supply of and demand for various goods is constantly changing and it is therefore a desirable phenomenon. Inflation, on the other hand, is an increase in the general, i.e. overall, price level (in simple terms, most prices in the economy) and is a manifestation of macroeconomic instability.

In order to avoid some unfortunate misunderstandings, let us therefore explicitly declare that by inflation we do not mean a rise in the prices of a few, or in prices in only certain sectors of the economy, but a rise in prices that is deeply pervasive throughout the economy and does not affect only some of its sub-sectors.

How High Has Inflation Actually Been?

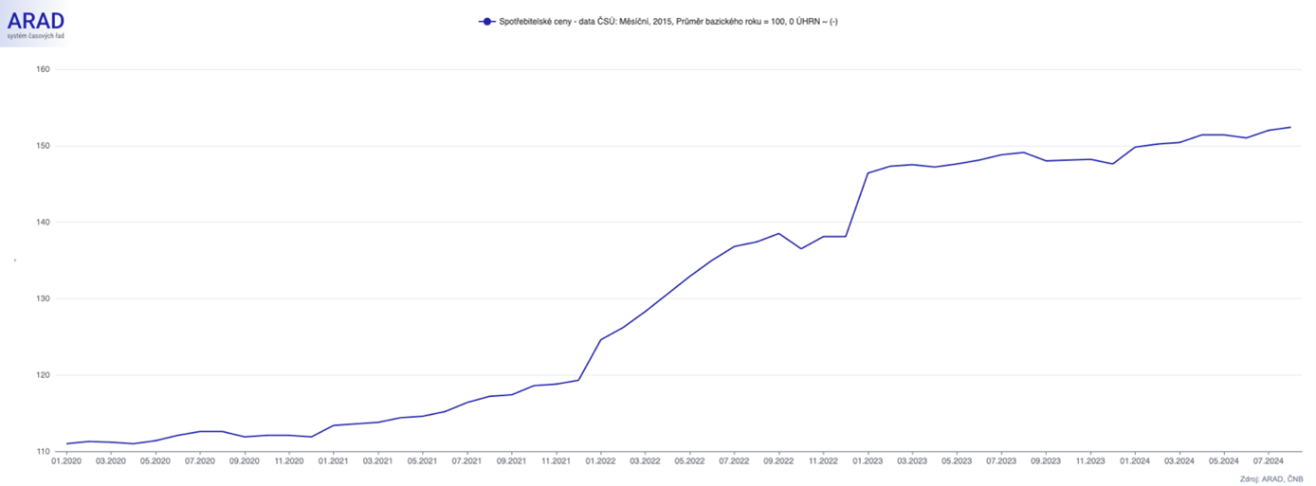

The price level as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI) increased by 37.3% in aggregate from January 2020 to August this year. This, in layman’s terms, means that the prices of most goods and services purchased by the average consumer in the Czech Republic have increased by about a third over the past four and half years. Meanwhile, the average inflation rate in the country over this period was 9.25%.

As the Czech National Bank (CNB) wrote in its Monetary Policy Report of late 2022, the period of exceptionally high inflation in the Czech Republic can be characterized by two main features. The first is the intensity of consumer price inflation itself, which is unprecedented in recent decades. The second characteristic feature of inflation is the breadth or spread of price increases across the items in the consumer basket, which is the measure of inflation. Thus, according to the CNB, the recent increase in inflation was not the result of a significant rise in prices for just a few items but was a widespread phenomenon.

Price level in the Czech Republic between 2020 and 2024

Source: Czech National Bank, ARAD. Note: Consumer price growth according to the Czech Statistical Office; monthly data, index: 2015, base year average = 100; aggregate; period: 01/2020-08/2024

The abnormally high rate of inflation was not, however, endemic in this country; on the contrary, it was present all over the world. In developed countries, it has even risen to levels last seen in the 1990s. This is the period when inflation rates were so high that they became the impetus that gradually prompted the world’s central banks to change their monetary policy regime, giving rise to the inflation targeting we know today.

Inflation in The V4 Countries

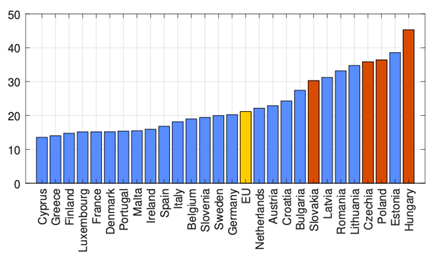

During the last inflationary wave, it was the Visegrad Four (V4) countries that consistently recorded some of the highest inflation rates. However, as outgoing CNB Board Member Tomáš Holub points out, the fact that the initial transition economies had the highest price level increases among the EU countries may be partly related to their real convergence.

Percentage change in the price level in individual EU countries between 2020 and 2024

Source: Czech National Bank (Dvořáková; Šestořád, 2024). Note: V4 countries in orange, EU average in yellow; period: 01/2020-01/2024.

The V4 countries share several important common characteristics that can be useful when examining their inflation trends. These include, for example, geographic proximity to Russia, higher energy intensity, less competition in retail markets, and lower initial GDP and price levels. Moreover, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Hungary are all very small open economies compared to the EU average.

The origins of the high inflation rates in the V4 countries were addressed in detail in a recent expert study by CNB researchers. Their findings indicate that in all these economies observed, external shocks have played a significant role in the recent rise in inflation rates. These included both demand shocks (e.g. the global trend of postponing consumption after the end of the COVID-19 pandemic) and supply shocks (e.g. the disruption of global supply chains and the impact of Russian aggression in Ukraine).

Global supply shocks, reflected in the rise in prices of energies and commodities triggered by the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and further accelerated by the war in Ukraine, have contributed substantially to higher inflation rates, especially in the period 2021-2022. In the case of the Czech Republic, however, the initial impulse for excessive price increases came from the rapidly rising core price component, the growth of which was driven mainly by domestic demand factors. It was only in 2022 that rising energy prices made a more significant contribution to the overall inflation rate in the Czech Republic.

This conclusion is not at odds with those put forward by the CNB study, as it also found that domestic factors played a very important role. It is these domestic factors that explain most of the differences in inflation rates between countries.

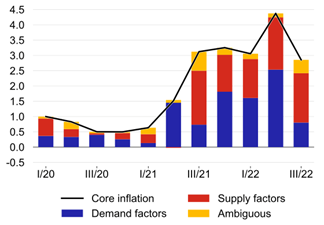

An earlier study by other CNB researchers from the end of 2022 shows that for most of the period from the beginning of 2020 to the third quarter of 2022, demand-side factors had a larger share in core inflation in the Czech Republic, but supply-side factors also had a crucial influence.

Percentage share of supply and demand factors in core inflation in the Czech Republic

Source: Czech National Bank (Brůha; Šolc; Tomanová, 2022). Note: quarterly data; seasonally adjusted; yellow columns indicate those inflationary pressures that do not fall directly into either of these two categories (e.g. inflation expectations).

Comparison with Abroad

Similar analyses have been carried out in other countries and by other research teams in recent years. A 2022 study by researchers at the European Central Bank (ECB) concluded that inflation growth in the euro area, as measured by the HICP adjusted for energy and food prices (HICPX), was mainly supply-side driven at the start of the third quarter of 2021. However, the importance of demand factors has gradually increased over time.

Adam H. Shapiro, a researcher at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, looking at elevated inflation (as measured by the PCE index) in the United States, in turn, presents the view that supply-side factors explain about half of the difference between annual inflation in 2022 and its pre-pandemic level. Demand-side factors then account for one-third of this, with the remainder attributable to those factors for which it is not possible to determine with such certainty whether they are supply- or demand-side.

Monetary Policy Response

It now remains to assess the monetary policy response of the Czech National Bank in light of the conclusions of the studies presented above. The CNB’s analysis from late 2022 emphasizes that, due to the significant contribution of demand factors to inflation in recent years, starting the monetary tightening cycle through the CNB’s interest rate hikes was the right strategy for restoring price stability. But this does not tell us much about whether the pace and timing of interest rate increases were right.

Nevertheless, another CNB study explicitly states that “central banks have not resorted to further tightening that could dampen inflation through monetary policy shocks.” With the benefit of hindsight, it is therefore evident that central banks did not raise their interest rates fast enough and to high enough levels, i.e. that their response to the rise in the inflation rate was far from optimal. It is telling that such a conclusion is now confirmed by some of the CNB’s top officials who were responsible for setting monetary policy in the Czech Republic.

The question now, however, is whether we will learn from the mistake of insufficiently restrictive monetary policy, partly justified by the allegedly purely cost-driven nature of the recent high inflation rate, in some future inflationary episodes. For, as Sir Karl R. Popper, one of the most distinguished philosophers of the last century, wrote in his book The Poverty of Historicism, “We will make progress if and only if we are ready to learn from our mistakes and realize our errors.”

Written by Stepan Drabek, analyst at CETA.

Continue exploring:

Slovakia’s Public Wages: Highest in V4, Exceeding EU Standards