INESS Policy Note 3/2012

Radovan Ďurana, August 2012

Quo vadis Pension System?

Summary

- The reform of the pension system will not eliminate large deficits in the foreseeable future

- Due to pension reform, the pensions of hundreds of thousands of people who are now economically active will fall by tens to hundreds of euros

- More reforms to follow, further decrease in pensions is very likely

- The pension system should be fully restructured, partial changes of its parameters are rather insufficient

A major pension reform was approved in a fast track procedure. The expense of this fast track procedure was not only the violation of legislative rules by the new parliament and government, but also lack of understanding of the long-term impact of this reform. The reform was approved in a bully-like approach with short sighted result. It cuts the need for financing of the deficit of the Social Insurance Agency from the state budget by roughly one third for the duration of the next 10 years. The government seems not to care what happens afterwards. This, however, should be of interest to all young working people, since not only are they going to end up paying higher contributions, but also, very likely, they will receive smaller pensions. In this paper, we critically comment on the reform of the first and the second pension pillar.

First pillar offers promises, but no guarantees

During the previous government of PM Radičová, a pension reform was proposed which took into consideration the demographic forecast and was supposed to keep the deficit of Social Insurance Agency (SIA) under control. The proposal offered relatively sustainable deficit of 1-1,5% of GDP[1].

Original measures, respective measures published in the IFP study:

– Gradual increase of the pension age from 2016 ( approximately 65 years between 2040 -2050)

– Changing the replacement ratio (increasing solidarity)

– Indexation of pensions by the pensioners’ inflation

– Decrease in the maximum contributions base (ceiling) to 3 times the average salary once the consolidated budget is reached (currently 4 times)

– Decrease in the growth of pension´s value when number of pensioners grows

The new government in its reform hasn’t discovered anything new. Instead of decreasing the ceiling for contributions base, it increased it to 5 times the average wage. The proposed relation between growth of pensions and the number of pensioners disappeared completely, which left the reform without the parameter that kept it sustainable (it took into consideration the negative demography trend and, therefore, the ratio between contributors and receivers). The new government also copied the model of the indexation by pensioners’ inflation (including the populist idea to index it by a lump sum) and gradual increase in the pension age. They cut down the contribution to the second pillar (from 9% to 4%) and transfered the cash flows in favor of the first pillar, which will lead to future growth of pensions expenditures from the first pillar.

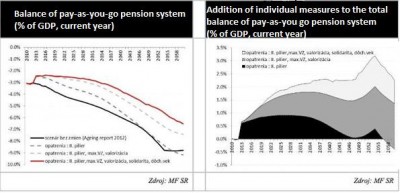

Despite this „reform effort“, based primarily on increased contributions, the long term balance of the pension system appears tragic. During the legislative process, neither the Ministry of Finance nor the Minister of Labour, published the long term balance. It was published informally by the head of the IFP on his facebook profile[2]. According to this chart (see below), the deficit meets solid 6% of GDP between 2050-2060. The current deficit, even including the „large“ second pillar, reaches 2,5% GDP. So, despite certain improvement (compared to most recent projections), the reform had not been so brilliant.

Source: Facebook profile of Martin Filko, head of IFP

(left chart black line – deficit before reform, red line – after reform)

Temporarily, the increase in the pension age and changes in the indexation support lowering deficit. Later on, these positive effects diminish due to negative demography (aging of population). Setting up the first pillar in such environment (fast aging population) means increase in the pension expenses, by 2060 the first pillar should redistribute 11-13% of GDP, compared to 8% in 2012. Once this point is reached, the pension system changes into a scheme where single economically active person will have to pay pension to a single pensioner and therefore this scheme could be called: „support your own pensioner“.

The first pillar is characterized by frequent changes and lack of guarantees. The average Slovak finds themselves in a very difficult situation. To define their own optimal pension strategy they must always start with predicting political risks and possible changes in both pillars. The lack of stability is a typical feature of Slovak pension system. The present, and probably also the future, leveling of pensions is a good example.

Source: Shooty, published with artist’s approval

Leveling

In case general public and politicians do not want to get rid of „safe, reliable“ pay as you go pillar, which “guarantees” the minimum replacement rate of pensions, they need to prepare for the leveling (equaling) of pensions. What the parliament recently approved is just the beginning.

The roots of the low trustworthiness of pension system could be found in its historical background. At the end of 2007, the parliament and the legislation kept promising that by 2015 the pensioner who paid contributions from treble average salary should also receive treble pension, when compared to a person who contributed from average salary (and therefore would receive average pension). Later, the first PM Fico government raised the maximum base for social contributions to 4 times the original amount (besides the unemployment and the sickness contributions). The second PM Fico government went even further when it raised the maximum contributions again, but this time to 5 times the original amount. Part of this reform was also lowering the maximum amount of pension to 2.3 of pension received from average salary contributions (see Box 2). Increasing solidarity in this case meant decreasing monthly pension by tens to hundreds of euros, depending on the income (Box 2). The victims of this reform were people with income over 1.25 time the average income. In 2010, there were 323 000 people in this category.

| Development of the pensions in Eur for selected income groups ( average salary in Slovakia – 800 euro) | ||||

| Monthly salary for the 40 years of employment | 1050 | 1200 | 1500 | 2000 |

| Pension under the Labor Minister Kaník (set up in 2007) | 525 | 600 | 750 | 1000 |

| Pension after PM Fico reform 2012 (in effect from 2018) | 515 | 560 | 650 | 800 |

| Decrease in pension | -10 | -40 | -100 | -200 |

This example illustrates the calculation of pension supposing there is no change in salary of an employee for 40 years, as well as no change in the average salary in economy. Should we use the dynamic variables, the result would be the same.

And what happens to „savings“ resulting from decreased high pensions? The government will not use the „saved“ money to decrease the deficit of SIA, but will use it for a permanent increase of lower pensions instead (this was meant to happen also in the Labor Minister Kaník set up, but it was meant only as a temporary measure lasting until 2015). This approach could be called solidarity, but only on condition that this solidarity included those who could not work more during their pre-pension age. In fact, the pension will also grow for those who intentionally avoided pension contributions, those voluntarily unemployed, housewives, etc.

From 2050 onwards, the expected deficit should reach 6% of GDP (which is currently almost the annual revenue received from the VAT – Slovak best earning tax), and, therefore, it is rather likely that the first pillar deficit is going to be decreased again by a similar method. It is, however, not possible to keep decreasing high pensions permanently due to the constitutional restrictions. Therefore, it is highly probable that in the future the government will also decrease the pension of average salary earners, not only high salary earners. Prepare for the possibility that in 20-30 years our current pension system will be considered generous[3].

This criticism should not be interpreted as a call for highly meritorious pension system. The merit is an inevitable characteristic of defined contributions of the pay-as-you-go pension system, but it is impossible to be executed in such an environment where one employed person needs to pay pension to one pensioner. The social system should be solid, which is in direct contrast with merit, which we consider undesirable (this is false logic: if I pay high taxes I should have the entitlement to state benefits, free education, high pensions, etc.., regardless of my income and wealth). The merit belongs to the commercial sector of individual insurance. The more I contribute, the higher the compensation then.

What is to be done with the first pillar? – proposal of measures

1) Change the system. Trigger a discussion about the meaning of contributions base form of the pension system where a leveling of pensions occurs and will occur, and consider a transition to defined benefit system financed from general taxes.

2) Increase the retirement age at a pace of 3 months per year from 2013 and when the retirement age of 65 is reached, re-evaluate the usefulness and speed of increase.

3) Apply the indexation of pensions according to pension inflation immediately (let us not wait 5 years for its full application). The extent of the indexation should be limited by the growth of collected contributions.

1) Change the system

It is not pleasant to compare a pension system to the Augeas stable, though in reference to the demographic trend and economic instability, the current PAYG merit system is not suitable for Slovakia. The incessant transfers from surplus funds of the Slovak Insurance Agency to pension PAYG fund can be considered a sign of disorder, too. The same is true for the Reserve Solidarity Fund, which has never been treated as a reserve. Regular changes and lowering of requirements increased the opacity and unpredictability of the system.

The first proposal is a paradigmatic change, abolition of the insurance-contribution principle, which, in the present days, promises some hardly achievable goals. From where we stand, a more fitting solution seems to be a gradual return to the benefit system, which will not simulate the insurance character and merit falsely, but will concede a solid allowance to the citizens without any property and income. In Slovakia, the merit of social systems does not motivate to pay contributions, which has been proved, besides other things, by the preference for self-employment jobs or contracts with no contributions paid. As for a higher standard, everyone should save up for themselves individually[4].

As we know, neither the previous coalition nor the current government is willing to discuss anything like this. Hence, we propose some politically debatable adjustments to the present system. These will not lead to such a high deficit, and thus will moderate the impacts of the current system on the future mostly not-yet living generations (for which we currently plan 6% deficit). Therefore, the objective is to set the present system so that in the period of the next 40-50 years it will not generate such a significant deficit as it happened after the already passed amendment. In contrast with the current government, we think that it is not the present deficit, but the future one that is a crucial problem. Current pensioners are not essential from the standpoint of the evolution of this problem. Those who are important, are the working people, to whom the unachievable is promised.

1) Age of retirement leave

Increasing the retirement age is necessary as of tomorrow. There is no legislative obstacle why the age of retirement leave should not be increased as of tomorrow[5]. Just the opposite, there is a great number of reasons in favor of this increase – the life expectancy in retirement age = the time for receiving our pension has risen by more than a year for both men and women since the adoption of Kaník’s[6] reform. For this reason, the suggested growth by roughly 50 days per year is inadequately slow. Latvians will increase the age of retirement leave from 65 years old at a pace of 3 months per year, whereas the Czechs by 2 months every year. For the present thirty-year-old people, the age of 65 will no longer be held, and 67 will appear instead. When moving by 3 months per year, the age of 65 for the retirement leave would come true in 12 years. Obviously, simplification of employing and flexibility of labour market is an indispensable complementary condition, so that such an environment is established where new jobs emerge (for the reasons see indexation below the chapter).

Indexation

The indexation by a fixed sum should be abolished and the indexation based on pension inflation should be established as of tomorrow. The indexation should be limited by the the nominal growth of income from contributions. The indexation by a fixed sum[7] planned for the next 5 years represents a transfer of resources from the “rich” pensioners towards the multitude with lower pensions. As a matter of fact, the parliament approved the real decrease in a part of pensions (even if it does not call it that way) just by a change in indexation. Decreasing pensions is one of the most serious steps (measured by political difficulty to pass such a change) in the modification of the pension system. These resources will not be used in order to decrease the deficit of the pension system, but for the indirect increase of lower pensions -without any analysis. The objective of the required pension distribution has not been set-up either (What is the ideal of this government? – all pensioners with an equal pension?) The government is not interested in whether a low pension has been caused by passivity, unwillingness to work, or whether it was an effect of health complications.

There is no good reason for a transition to indexation by pension inflation in the same gradual 5-year-taking way. In 2012, the budgeted deficit of pension system was 1.8 billion euros. Recently legislated reform will increase the contribution burden for tens of thousands of employees by hundreds of euros, whereas for hundreds of thousands to tens of euros. An immediate implementation of pension inflation would slow down the indexation of pensions in terms of single euros. Therefore, immediate indexation by pension inflation could hardly be considered too austere, especially when the purchasing power of pensioners could be preserved.

A discussion about the indexation is necessary, but the decision, which macroeconomic variable should the formula include is less significant than the fact that the indexation is in no way limited by an increase in contributions, which are paid by working people. If the working generation faces high unemployment, the average salary and a number of working people do not increase (or if a government is not willing to increase the transfer among generations), hence if income contributions do not grow in nominal terms, what shall be the source of pensions indexation? Is it possible to increase pensioners’ income when the working population does not have higher income? This is the reversed facet of the pay-as-you-go system, which is usually overlooked or even forgotten. This PAYG system is favored among many when there are 5 people working for one pensioner. Nevertheless, once the situation is changed, pensioners neglect the fact that it is the working population that conditions their welfare, not the government. During their working life they have paid high contributions, and now should the purchasing power of their pensions decrease? The truth remains that the PAYG system has the form of a pyramid game as pensions of the currently working people will not be paid out from the profits of their contributions, but from the contributions of participants of this game who have not been born yet. Strangling the present as well as the future labor force by high contributions and taxes may likely result in scoring an own goal.

Second pillar

Why is the second pillar important?

The parliament approved the decrease in the contributions rate to the second pillar from 9% to 4%. Such change should increase the future demands on expenses of the first pillar. Nevertheless, a brief look at the chart on page 2 indicates that the evolution of the deficit shall be in contrast to the expectation. It can be explained by a shift of positive effect of savings pillar beyond 2060[8]. Hence, by 2040, the PAYG system “will be supported” by higher revenues due to a higher income from contributions (an effect of the smaller second pillar), better demography (a higher estimate of the number of working people in 2040) and mainly by a lower number of new entrants into savings scheme due to opt-in set up (change from opt-out).

This does not mean that the lowering of contributions for the second pillar is the right step. Surely, the second pillar has a great deal of shortages, and basically it is only regarded as the third best solution. The first solution would be bestowing the responsibility for pension saving upon the public, and the second one would account for compulsory savings, though in a substantially less restricted, less regulated environment with a possibility to put aside the savings in correspondence with the needs of the saver. The current setting is hardly understandable from many standpoints. You can try to answer the question why a person, with 4000 euro income per month, should save compulsorily from his whole salary in funds with an uncertain outcome, while, let us say, they are paying off a mortgage for the house they live in? Or, what is the difference between the pillars when the first promises a salary based on the future contributions, while the second does the same on the basis of the future taxes (in 2010, according to OECD, roughly a half of savings were invested in government bonds)? The second pillar needs to be essentially reformed, yet in a different way then it has been done to date.

Despite any shortages, the second pillar should be preserved, for it serves its two basic purposes. In one way, it restores the personal responsibility for wellbeing during pension age. This is a process that takes tens of years. The present setting of the second pillar, in which a saver has minimal incentives to actively manage their savings, which is due to the transfer of all powers and liabilities to the DSS[9], prolongs the process in which a person “gets used” to the personal responsibility. From this point of view, the second pillar can bear some fruit in the form of a more active approach of savers in the course of tens of years (it is for this reason that nowaday’s research carried out about financial literacy shows such poor results. Understandingly, a mass of savers do not understand the risks and opportunities of the investing process, as the government has set up for them the DSSs, which should possess the skill.) The “getting-used” to saving and to your own responsibility will be brought about gradually, and the first payments from the funds will play an important role in this regard. Diminishing the importance of saving is, in this respect, counterproductive. Of course, in the minds of people a small amount of money devaluates the savings scheme to a sort of a bonus, which will not be taken away immediately by the State. Nevertheless, compared to Hungary, the second pillar has survived, we should just remember that its substantial reduction occurred at the deficit of SIA, which is less than a half in comparison with the projection in 2060.

In contrast to immediate decrease of contributions to 4%, the parliament also approved a gradual increase of contribution to 6%, which will perhaps come into force in 4 years’ time, and will reach the rate of 6% only in 2024. It can appear as a signal that the current government considers the second pillar an acceptable way of the reform of pension system. However, how does this signal match the implementation of the voluntary entry to the second pillar, which is an unambiguous expression of mistrust vis-à-vis the second pillar? It is the abolition of the automatic entry (with a long-term maturity for opting out) that is the crucial weakening feature of the reform of the second pillar. Decrease in the number of savers is a far more important issue as it defines the political strength of this scheme, slower growth of administrated volume of finance due to lower contributions is less important from this point of view. It is estimated that only 10 -15% of the new entrants to job market will enter the second pillar.

The second function of the second pillar is the fact that it lowers a high tax-contribution burden of workers (today roughly 50% of the cost of labor). The transfer of savings into the first pillar will be for a part of the population (with salary above the average one) de facto a tax, as it will not increase their pension claims, nor the claims of their heirs. The reform of the second pillar will decrease the level of freedom due to imposed higher taxation.

Voluntary contributions?

New feature has been added to saving scheme. Voluntary contributions (max. 2%) to personal account will be allowed with the tax shield limited to 2% of gross salary.

An improvement or not? In the situation where every well-informed taxpayer poses himself a question whether or not the second pillar will survive, this option should be deemed as an uninteresting offer. On the other hand, the voluntary contributions could increase the chances of the second pillar’s survival, as it will no longer be perceived as “a contribution stolen from the budget of the Slovak Insurance Agency”.

Bonds or stocks?

Side by side with the evaluation of the second pillar’s reform, there is almost no mention of “optional” switch of savers to guaranteed bond funds and of the abolition of the duty to keep index funds. Those are the steps underpinning “the conviction” of the current government of (un)importance of the second pillar.

The setting up of the second pillar could be described as a sinusoid. Former PM Fico government introduced guarantees, next government limited them to conservative funds and introduced index funds. The new Fico government decided to simplify the portfolio to guaranteed bond funds and equity funds without guarantees (index funds, the cheapest option for savers has been effectively cancelled without explanation). But the government does not like the current structure of savings, which are mostly in equity funds (don’t be confused with the name, even in these funds, the majority of savings lies in bonds and cash equivalents). Therefore, the managers of funds will have to contact the savers with the inquiring, whether they are willing to stay in a fund without a guarantee. The savings of those who will not answer “no” will be automatically transferred into a guaranteed fund. The way the government asks is not a coincidence. Most of the savers lack the knowledge and interest in management of their savings. Having no incentives, we can expect only limited number of answers. Thus, the government has decided on the saver’s behalf. It is a similar strategy to the one of the voluntary entry to the second pillar. Our aim is not to sell the not-guaranteed funds of the DSSs. Conversely, it is to warn about the non-conceptual approach towards the second pillar. The contradiction is encapsulated in the fact that the idea of the second pillar itself is primarily based on the ability of stock markets to appreciate invested resources and decrease the dependence of pension system on tax revenues in Slovakia. The investors in the age of an average Slovak saver are advised, according to the standard textbooks of investing, to control the appropriate share of stocks. Although equity funds do not meet (and never did) the lower limit of the “appropriate” share of risky equities, the government forces the inactive savers from these funds into the guaranteed ones. One must ask, why then the law that regulates savings contains a “safety fuse” which does not allow any equity, like risk exposure, after reaching 50 years of age.

How to proceed – an overview of proposed measures in the second pillar

The following proposals take into account the current political conditions and they attempt to enhance parametrically the existing setting – not to reform the second pillar from scratch.

1) Decrease the limit for contributions base into the second pillar to 2-3 times the average salary. This change would increase the taxable base and net cash of the savers. Employees with an over-standard income have a great deal of opportunities in order to appreciate their own resources (real estate, the education of their own children, and so on and so forth). The increase of the base for contributions makes sense for the first pillar (from the government point of view), but not in the second pillar, especially when there is no guarantee that the second pillar will not be dramatically changed or even abolished.

2) Abolish the duty to confirm the disagreement with the transfer of savings to the guaranteed fund. When the government considers the high share of savers in an equity fund to be a result of financial illiteracy, it should focus on this problem, and not force savers out into the funds with a low potential of appreciation.

3) Ease the regulation of the DSS, which will allow the creation of new more flexible subjects. As the right amount of payments is hard to define, we are in need of more competition. The limitation of regulation means also widening the investment options of the DSS.

4) Maintain the up-to-date valid provision, which will enable savers to opt-out from the second pillar in a suitable time period.

Conclusion

It seems that the government will be able to conserve the deficit of the first pillar at 2% of GDP for the next twenty years, whereas roughly 0.6% of GDP will be a consequence of the existing second pillar, and 1.4% will be caused by the unsuitable setting and by a high unemployment rate. A slowdown of the growth of the pension system deficit will result from an increase in contributions of the people with higher income, a reduction of the second pillar, and partially also a gradual growth of the age of retirement leave. Subsequently, it is inevitable that deficits should start to rise faster. Today, those who will retire in twenty years should re-evaluate their public pension expectations thoroughly. Postponing necessary balancing of revenue/expenditures of the system will mean higher costs of reform in the future. These will be either in the form of lower pension, higher contributions and an even later retirement age, or it can be a combination of all of them. The pension system continues to be an unsolved problem.

INESS, in Bratislava

30 August 2012

[1] the impact of proposed measures was calculated based on original demographic prognosis from 2008, new prognosis released in 2012 would amend the impact. Annually, employees participating in the second pillar transfer around 1-1,2% GDP in contributions to their accounts.

[2] The long term impact of the pension reform were first released together with the 2013 budget proposal in the middle of August 2012

[3] Currently after 40 years of average salary the pensioner receives €392, which is 62% of average net salary

[4] Lower pensions could, to a certain extent, have a positive influence on higher fertility, see for example a study concerning pension system and fertility

https://editorialexpress.com/cgi-bin/conference/download.cgi?db_name=IIPF66&paper_id=344

[5] As far as women are concerned, there would be a more complicated pattern influenced by the process of catching-up with men which is underway

[6] For the simplicity of the comparison we will use the indication of „Kaník’s settings“ and „when Kaník was in office“ for the versions of the law about Social insurance before 2008.

[7] Based on indexation formula (combining growth of average salary and inflation) the calculation of an increase of average pension will be done. The nominal increase at an average pension will be used to increase all the pensions.

[8] This fact was pointed out in a material of MF SR– Implicit commitments

[9] Pension fund managenent company