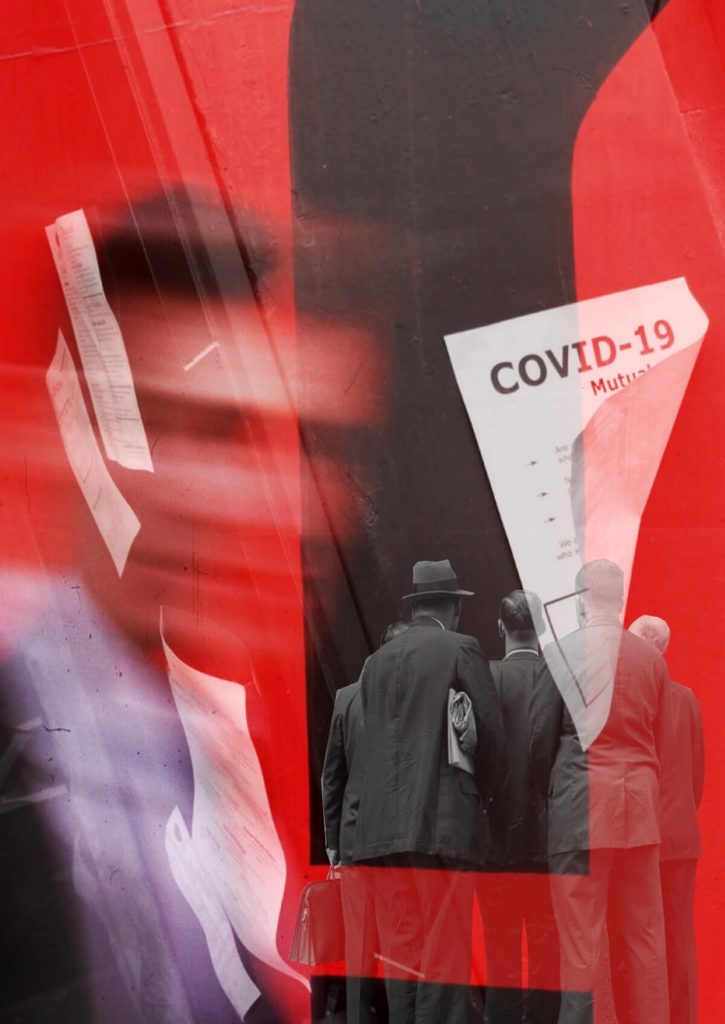

The COVID-19 pandemic triggered a boom in the use of digital solutions like Zoom or Microsoft Teams, enabling employees across the world to continue working at home, away from their now empty offices. Some companies have struggled to adapt, clinging to the hope of a speedy return to the old normal. Others, like Google, Microsoft, and Spotify, have been more open to change, announcing that their employees will be able to continue working remotely, indefinitely.

Remote work might well be on course to becoming the new normal of the 21st century. Historically, the locality of work, be it the home, the factory or the office, had an impact on women’s representation in the labor market and gender relations, both positively and negatively. What will be the long-term impacts of COVID-19-induced remote work on gender equality?

Women’s Remote Work Throughout History

It is not the first time in history for workers to make their income from their kitchen tables. The emergence of capitalism in Europe between the 17th and 19th century took place not in the factories but, for the most part, at home. Workers produced consumer goods on large kitchen tables or small workshop spaces attached to family houses. This work was mostly carried out by women and children who were unlikely to write biographies, leaving behind little historical trace.

Download full article:

MARIA SŁOMIŃSKA-FABIŚ THE EFFECTS OF COVID-19-INDUCED TRANSITION TO REMOTE WORK ON GENDER EQUALITY

Through limited existing records, depictions in literature, and even architectural clues, historians paint a faint picture of home-working women. These women operated on highly varied time schedules, juggling diverse sets of tasks, while also – compared to that of a factory worker – enjoying greater individual autonomy to decide their workloads and weekly outputs.

The emergence of the at-home industrial workforce was fueled by the expansion of global trade from the 1600s onward and raising individual incomes, thus a growing demand for manufactured goods1. Before the invention of the spinning jenny in the 1760s, the first consequential emerging industrial technologies were relatively small-scale and fitted better into the home than the factory.

Workers operated more like independent contractors than hourly salary employees, getting paid per finished product, often working longer hours than those in the factory. The economic historians Jane Humphries and Ben Schneider of Oxford University warn against glorifying the 18th century home worker2.

Dispersed across the country, they were vulnerable to exploitation from bosses. Unable to unionize quickly like factory workers could, they had little leverage to demand better pay.

The migration of productive labor from home and into the factory had far-reaching consequences, argue Humphries and Schneider, notably on women’s presence in the labor market. Despite its shortcomings, home-based work allowed women to engage in paid labor alongside domestic responsibilities, which men seldom took part in.

While by no means an easy task, women could contribute to the household income while looking after the family – a tricky balancing act, unsupported by the factory system. With industrialization, women’s participation in the labor market fell, increasing their financial dependence on men3.

Fredrich Engels believed the departure of productive labor from the home had a negative effect on gender relations4. He argued that women’s oppression originated from the specific structure of the family in a class society. In pre-class egalitarian societies, labor was divided by sex. Still, because much of productive activity happened in the sphere of the home, women’s positions in society were secured by their productive power.

Engels attributed the development of private property and migration of productive labor from the home into the factory as the main cause of the hierarchical relationship between the sexes, leaving women behind in the home to perform unpaid labor5.

1 The Economist (2020) “Home-Working Had Its Advantages, Even in the 18th Century”. Available[online]: https://www.economist.com/christmas-specials/2020/12/16/home-working-had-its-advantages-even-in-the-18th-century

2 Horrell, S., and J. Humphries (1995) “Women’s Labor Force Participation and the Transition to the Male-Breadwinner Family, 1790-1865”, [in]: The Economic History Review,No. 48(1), new series, pp. 89-117.

3 Ibid.

4 Pelz, W. A (1998) “Class and Gender: Friedrich Engels’ Contribution to Revolutionary History.” [in]: Science & Society, No. 1(62), 1998, pp. 117–126. Available [online] www.jstor.org/stable/40403691

5 Sandford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2004) Feminist Perspectives on Class and Work. Available [online]: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/feminism-class/