Hungary’s right-wing government, since Fidesz’s first landslide victory in 2010 and their subsequent successes in 2014, 2018, and 2022, has been increasingly willing to put cultural issues, particularly gender and LGBT+, at the forefront of its campaigns.

Fidesz’s framing of the issue regularly contained the need for children’s protection rather than overt attacks on sexual and gender minorities, which was most apparent in their bill merging the stricter punishment of pedophile criminal offenses with curbing LGBT+ representation in print and digital media. As Prime Minister Viktor Orbán said in October 2020 “they should leave our children alone.” This campaign slogan fit into the election campaign of 2022, which was accompanied by a referendum initiated by the government to protect children.

In this article, after detailing the antecedents, the circumstances, and the outcomes of this plebiscite, a possible way of improving Hungarian LGBT+ people’s rights and acceptance will be presented.

Transgender People’s Gender Recognition Shut Down

As a forerunner of Fidesz’s focus on LGBT+ issues, in the new constitution dubbed Basic Law, which has been in force since 2012, they codified that only a man and a woman are eligible to enter into marriage, a provision not included in the previous constitution, approved after the fall of communism. The government’s more concentrated efforts to roll back LGBT+ rights in Hungary started in May 2020 by making it impossible for people to change their gender on official papers.

As per the bill, ‘biological sex’ replaced ‘sex’ on birth certificates, which is a person’s biological sex assigned at birth based on one’s primary sex and chromosomal characteristics. The bill also stipulates that one’s biological sex cannot be changed, as a consequence, transgender and intersex people may have to carry IDs and other official documents which do not fit their identity and/or appearance.

The non-governmental organization Háttér Society, advocating for LGBT+ rights, underlined that without appropriate official documents, transgender people “cannot access suitable healthcare services, must constantly explain themselves while applying for a job, renting an apartment, running errands at a bank or even paying by card at a store.”

The Constitutional Court of Hungary partly struck down the law due to the fact that it prohibited gender recognition even before it came into force, as it violated the principle of no retroactive legislation, consequently, those who applied before 29 May 2020, managed to gain recognition of their gender. However, in February 2022 the Constitutional Court ruled that the law itself, that is banning gender recognition from 30 May 2022 onward, was not unconstitutional.

Háttér Society, claiming that the provision violated the fundamental right to human dignity and the right to privacy, was appalled at the decision and turned to the European Court of Human Rights, arguing that the Hungarian court contradicted itself, since in 2018 they had concluded that “all people have an unalienated right to a name and bearing thereof which expresses their self-identification” as it formed part of the right to equal human dignity.

Effective Exclusion of LGBT+ Applicants from Adoption

Also in 2020, Fidesz changed adoption regulations, making it harder for single applicants (except for family members or spouses) to adopt a child requiring the case-by-case approval of the minister responsible for family policy, who as of now is the Minister of Culture and Innovation. The decision was heavily criticized, as it handed over a responsibility previously belonging to the child services to a political appointee. As same-sex couples are legally unable to adopt a child in Hungary, they can only apply as single individuals. However, this legislative change has made them dependent on the minister’s consideration, János Csák, Minister of Culture and Innovation.

That same day, the Fidesz-supermajority in parliament amended the Basic Law as well, doing so for the ninth time, including a passage in it stipulating that Hungary protects the institution of marriage as a voluntary union between a man and a woman as well as emphasizing that “the mother shall be a woman, the father shall be a man.”

The amendment also declared that “Hungary shall protect the right of children to a self-identity corresponding to their sex at birth, and shall ensure an upbringing for them that is in accordance with the values based on the constitutional identity and Christian culture of our country.“

In December 2022, the Ministry of Culture and Innovation was unwilling to publish how many adoptions by single people they had approved or rejected, saying that they considered expert opinions as well as the aforementioned provisions of the Basic Law.

Restriction on Representation for Children’s Sake

In 2021, another bill concerning LGBT+ issues caused upheaval. Act LXXIX entered into force in July 2021, the original objective of which was to facilitate the prevention, detection, and punishment of pedophile criminal offenses. By way of a last minute amendment, however, provisions related to the LGBT+ community were added as well.

As the LGBT+ advocate group Háttér Society points out, “the act amended the Child Protection Act, the Family Protection Act, the National Public Education Act, the Advertisement Act and the Media Act to introduce a ban on access of minors to any content that ‘propagates or portrays divergence from self-identity corresponding to sex at birth, sex change or homosexuality.'”

Products with such content can only be sold at a distance of 200 meters from the entrance of any educational, youth, or religious institution, and even if 200 meters away, they have to be in sealed packaging and separated from other goods.

The act passed with a right-leaning opposition party, Jobbik, crossing the aisle and supporting it, in spite of Fidesz alone having the votes needed. The European Parliament adopted a resolution condemning the act “in the strongest possible terms […], which constitutes a clear breach of the EU’s values, principles and law.”

While EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen called it a “shame”, the Hungarian government responded arguing that it “protects the rights of children, guarantees the rights of parents and does not apply to the sexual orientation rights of those over 18 years of age, so it does not contain any discriminatory elements.” In December 2022, the European Commission initiated an infringement procedure against the Hungarian government in connection with the act.

The Act’s Effects

According to Háttér Society, the law mainly led to voluntary censorship by media outlets, private and public institutions. Some TV channels may refuse to air content related to sexual and gender minorities or are forced to classify them as category V, meaning only suitable for audiences over 18 years of age.

Nonetheless, the exact meaning of the law is also questionable, as Dávid Vig, director of Amnesty International underscored at a conference organized by Republikon that its interpretation is not evident at all. Luca Dudits, communications officer of Háttér Society also explained in an interview with 444.hu that due to the vagueness of the law and the uncertainty around what LGBT+ portrayal playing a central role means, the practice of the National Media And Infocommunications Authority has not been quite consistent.

Moreover, based on reporting done by lakmusz.hu, as of January 2022, the authority has not penalized any broadcaster settled in Hungary, however, there have been six instances in which they have approached foreign authorities in connection with content published by media outlets settled outside Hungary. Their complaints were to no avail, all authorities dismissed their Hungarian counterpart.

Pursuant to the vaguely phrased law, in bookshops, LGBT-related content is required to be sold in separate packaging, which led to larger chains shifting its financial burden on publishers. What is more, customers have to ask for such books explicitly as they cannot be on display, another factor putting them into a financially detrimental position. In libraries, books dealing with LGBT-topics are also available only upon request. The act had significant effects on education as well: it set forth that only experts and organizations registered by a government agency may conduct sexual education in schools.

However, – as Háttér Society specifies – “for over 12 months now, no public body has been designated and there is no procedure for such registration. This means that currently teachers cannot invite any external programs to schools to talk about sexuality.” In summary, the actual realization of the regulations set by the law regarding LGBT+ representation has been incomplete and inconsistent at best, underscoring the argument that its objective was not what the government claimed it was.

Let’s Take It to People

The restrictions on gender recognition, adoption and the so-called “Child Protection Act” turned out to be merely the beginning. As Háttér Society claims, it “was part of a broader anti-LGBTQI campaign of the government that culminated in a referendum held on the same day as the national election.” In July 2021, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán announced that the government would propose to hold a referendum on child protection.

“This time, Brussels demands that we alter the acts on education and child protection. They denounce that it is not possible here what has become normal in Western Europe. Sexual education is carried out by LGBTQ activists in kindergartens and schools there. They want us to do the same, that is why Brussels bureaucrats are threatening us with infringement procedures, meaning that they are abusing their power” – said Orbán in the video, a reaction to EU officials lambasting Act LXXIX.

The government clearly framed its steps and the consequent referendum as a question of child protection rather than a human rights issue affecting a minority and free speech. The questions posed to Hungarian citizens reflected this approach:

- Do you support holding lectures on the topic of sexual orientation to underage children in public education institutions without parental consent?

- Do you support the promotion of sex reassignment treatments for underage children?

- Do you support the unrestricted exposure of underage children to sexually explicit media content that may affect their development?

- Do you support exposing underage children to media content showing gender change?

The fifth question proposed by the government, “Do you support making sex reassignment treatments available to underage children?”, was first annulled by the Curia, the highest judicial authority of Hungary, however, the Constitutional Court overturned that decision. But the Curia annulled the question again for the second time, compelling the government to contend with the four questions above.

The Hungarian Civil Liberties Union, a human rights NGO, believed the referendum to be unconstitutional, claiming that it encroached on children’s and parents’ fundamental rights, hollowed out the institution of plebiscite as it was not clear what the parliament was supposed to legislate on in light of the results, in addition, no referendum could be held on questions that violated the Basic Law. Nevertheless, the Constitutional Court rejected their motion and made way for the plebiscite to go ahead on the same day as the parliamentary election, 3 April 2022.

“To Invalid Question, Invalid Answer”

During the referendum campaign, closely intertwined with the parliamentary election, activist groups encouraged people to vote invalid, as did opposition parties. Péter Márki-Zay, the opposition bloc’s candidate for prime minister called the questions raised “stupid” and did not deem them a real issue. He ended up casting an invalid ballot and promised to revoke the act if elected.

In contrast, as the online news site Telex underlined, “the governing parties used taxpayers’ money to finance ads ‘for social purposes’ on TV to show a girl telling her mother that instead of writing a math test, someone came into her class and told her that she could be a boy if she wanted to.“

Two NGOs, Amnesty International and Háttér Society, joined by nine others, mounted a campaign called “Vote invalid” with the slogan “To invalid question, invalid answer” in order to fight back against what they described as “the government’s homophobic and transphobic politics.” The NGOs argued that “the wording of the question was manipulative on purpose: it attempts to exploit parents’ natural concern and protective intention to further their own political goals.”

During their campaign, they also cited opinion poll results supporting their claim that Hungarian people see through the government’s “propaganda” and in general are more supportive of LGBT+ people than what the government’s policies may suggest. According to a survey conducted in July 2021, 66% of people considered it right to include information about sexual minorities in school curriculums, and 90% were of the opinion that age-appropriate sexual education ought to be provided in school. What is more, 83% said that it is not true that one can become gay after hearing about it in school.

And Results Are…

First and foremost, the number of valid votes did not reach the threshold of half of eligible voters by any of the questions (4 107 652 to be precise), so the referendum was declared invalid despite the government’s efforts to maximize turnout by coupling it with a parliamentary election. Thanks to the campaign to invalidate the referendum, however, around 21% percent of Hungarians cast an invalid ballot.

If we compare the referendum results to the party list preferences at the simultaneous parliamentary election, 3 060 706 people opted for Fidesz-KDNP with an average of 3 676 642 citizens voting “no”, thus 600 000 more supported Fidesz’s position at the referendum than their party list nationwide. In turn, 1 947 331 people backed the opposition bloc compared to 1 744 883 invalid votes on average at the referendum.

As it has been pointed out, winning a referendum is considerably harder in Hungary than winning a parliamentary election due to the 50% threshold in the case of the former and the unproportional nature of the latter, which makes it possible for Fidesz to win a two-thirds majority in parliament, yet have a referendum defeated. In brief, their voter base was enough for such electoral triumph, but insufficient for a valid referendum result. As there were four questions to decide, the exact results varied depending on the question.

| 1. Do you support holding lectures on the topic of sexual orientation to underage children in public education institutions without parental consent? | |||||

| Valid | 3 910 436 (47,60%) | Yes | 300 282 (7,68%) | No | 3 610 154 (92,32%) |

| Invalid | 1 717 702 (20,91%) | ||||

| 2. Do you support the promotion of sex reassignment treatments for underage children? | |||||

| Valid | 3 880 381 (47,23%) | Yes | 158 447 (4,08%) | No | 3 721 934 (95,92%) |

| Invalid | 1 747 757 (21,27%) | ||||

| 3. Do you support the unrestricted exposure of underage children to sexually explicit media content that may affect their development? | |||||

| Valid | 3 872 161 (47,13%) | Yes | 180 785 (4,67%) | No | 3 691 376 (95,33%) |

| Invalid | 1 755 977 (21,37%) | ||||

| 4. Do you support exposing underage children to media content showing gender change? | |||||

| Valid | 3 870 042 (47,11%) | Yes | 186 938 (4,83%) | No | 3 683 104 (95,17%) |

| Invalid | 1 758 096 (21,40%) | ||||

After the referendum, the government emphasized the resounding majority of “no” votes, while opposition groups welcomed the invalidation, however, analysts also underlined the questionable nature of the plebiscite, as its actual use in terms of public policy and its legal consequences, even if it had been valid, were unclear.

What was clear, nonetheless, was Fidesz’s objective to keep controversial LGBT+ issues on the agenda in order to increase turnout and antagonize gender as well as sexual minorities. The hostility spilled over to the NGOs representing their interests too, afterwards, the National Elections Commission fined Háttér Society and Amnesty International for allegedly abusing their rights and undermining the referendum by urging people to vote invalid. This reprimand was later rescinded by the Curia, arguing that the NGOs were exercising their fundamental rights and the invalid vote was a legitimate way of expressing one’s opinion.

LGBT+ People in Today’s Hungary

As it has been already detailed, LGBT+ and so-called “gender” issues have been at the forefront of public debate in recent years, and the government has consistently approached them from a place of ignorance, disparagement, and vilification. Háttér Society published the results of an opinion poll conducted in the first half of December 2022, which examined Hungarians’ attitudes toward LGBT+ people. They emphasized a number of findings, the first ones being that Hungarians’ perception of LGBT+ people has not deteriorated despite the efforts of the government.

In 2022, half of respondents signaled that they had an LGBT+ acquaintance, a significant rise from a fifth of them in 2018, a fact proving that more and more Hungarians are comfortable coming out, according to Háttér Society . In contrast to the government’s policies, 72% said that people ought to be allowed to change their birth name and sex, 60% opposed censoring the portrayal of LGBT+ people on TV, and 62% agreed that it is the state’s duty to combat discrimination against LGBT+ people. In terms of parenting, 56% backed making adoption possible for same-sex parents, and two-thirds agreed with the statement that same-sex parents can be as good parents as their opposite-sex counterparts.

In another report from 2022 by Tárki Social Research Institute, they examined the acceptance of gay people over the course of two decades. In 1990, “three quarters of Hungarian respondents (75.3%) would not have liked to have homosexual neighbors, while by 2008 this proportion fell sharply (29.5%) and by 2018 it somewhat grew again (36.2%).”

They attribute this spike to the general growth in the rejection of different social groups: “Hungarian respondents in 2018 gave all the neighborhood categories a higher rejection rate than ten years ago, and of all the categories surveyed it was homosexual neighbors who showed the least increase in rejection (rejection rates rose most toward immigrants and Muslims).“

Notwithstanding, it is noteworthy that this data predates the government’s anti-LGBT+ campaign picking up steam. On the whole, it thus seems safe to assume that there are dots to connect between the government’s previous campaign against immigration and last year’s referendum, both of which focused on minorities perceived as other. Adding to this, researchers at Tárki found that “there is a positive correlation between the acceptance of immigrants and the perception of gay and lesbian adoption.”

The report also goes on to claim that “Hungary is one of the less accepting European countries, but at the same time Hungarian society as a whole can in no way be considered homophobic.” In comparison to other post-soviet, current EU member states, Hungarians’ acceptance of homosexuality in 2019 was just above average: in the Czech Republic, it was 59%, in Hungary 49%, in Poland 47%, in Slovakia 44%, in Bulgaria 32%, and in Lithuania 28%.

However, a slight generational divide can be observed in Hungarians’ attitude, just like in most Central and Eastern European countries: 65% of young adults (18-29 years old), 57% of 30 to 49-year-olds, and 37% of seniors (older than 50) find it acceptable. In sum, people younger than 50 tend to be accepting of homosexuality, furthermore, as Tárki underscored, this is also true about women, those with higher education, urban residents as well as people who do not attend religious ceremonies on a regular basis.

What Could Be Done to Improve LGBT+ Rights in Hungary?

All in all, it is a mixed picture when it comes to Hungary and LGBT+ rights. Although Hungary is a relatively accepting country in regional comparison and opinion polls paint the image of a rather tolerant society, the Fidesz government’s antagonistic approach and rollback of LGBT+ rights cannot be cause for optimism. In what follows, a number of recommendations will be offered to improve LGBT+ people’s rights and lives, starting from the ones that require the least legislative action and could be implemented immediately and concluding with long-term measures that would even entail constitutional amendments.

For starters, a positive change in the government rhetoric regarding LGBT+ people and the issues affecting them would instantly contribute to the creation of a social atmosphere that is more accepting and empathetic. From an administrative perspective, the restrictions on single parents’ adoption, which impacts same-sex couples who are only eligible to apply as single parents, could be circumvented easily if the minister for family policy, considering the recommendations of child services professionals, were to grant permission to all suitable single applicants as well.

In terms of sexual education, it would require no additional legislation to comply with the existing law and establish the official register for NGOs so that they are able to impart information and provide counsel to adolescents on sexual and gender identities. Education involving non-heterosexual orientations is already fairly backed among Hungarians, as per Háttér Society’s survey, “one in two respondents tended to agree with the statement that it is right for young people aged 14 to 18 to be exposed to the topic of homosexuality in the school curriculum.”

With respect to medium-term legislative prospects that only require a simple majority in parliament, the provision rendering it impossible for people to change their gender as well as Act LXXIX restricting the representation of LGBT+ people ought to be repealed (in tandem with the act restricting adoption). As already alluded to, Háttér Society claims that 72% support reinstating the availability of gender recognition with 60% being against the censorship of LGBT+ people on TV. These policies would only mean a return to the status quo before 2020, not mentioning the aforementioned amendments to the Basic Law.

However, since they are mostly symbolic with no actual effect on public policy (except for the stipulation of marriage only being between a man and a woman), and can only be altered with a two-thirds majority, it would be more feasible to focus on measures not necessitating the long-shot of having a supermajority in parliament.

Path Forward in Coming Decades

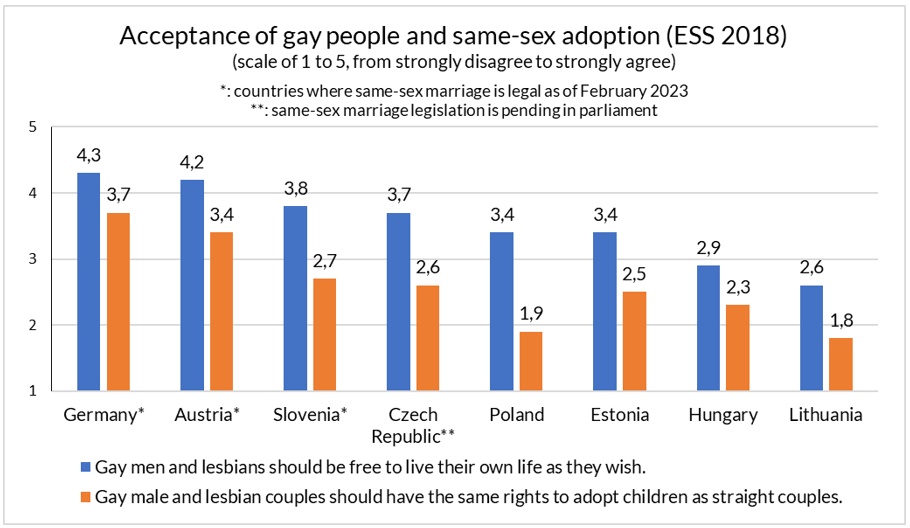

In my view, long-term legislative proposals to improve LGBT+ people’s situation should concentrate on childcare and the expansion of the rights encompassed by registered civil partnerships introduced in 2009. In comparison to other Eastern and Central European countries, despite having relatively low acceptance rates regarding homosexuality in general, Hungarians’ attitudes toward same-sex parents stands out in regional comparison based on the European Social Survey’s ninth wave carried out in 2018. For instance, despite the fact that in Poland (where civil unions are not legal) general acceptance is higher by 0.5 points, Polish support for same-sex parents’ adoption rights is significantly lower than in Hungary.

In addition, according to the European Values Survey in 2018, when asked if same-sex parents can be as good as any other couple, 8% agreed completely, 18% partially, 28% was neutral on the question, 24% disagreed partially, and 22% disagreed completely. This means that only 46% discarded the statement and the majority of Hungarians was supportive or had no particular opinion on the subject.

An important caveat is that all this data was collected before the referendum on child protection, however, there are no comparable figures available since then. For what it is worth, as already mentioned, Háttér Society claims that 56% of Hungarians backed same-sex adoption, and 66% said that same-sex parents can be as good parents as their opposite-sex counterparts.

This leaves an opportunity for broadening registered partnerships and closing the gap between its legal standing and that of marriage in terms of wealth distribution and inheritance for example. Another step would be making it possible for same-sex couples to take each other’s name and to be able to adopt each other’s or non-related children. It would be most advisable to implement these measures at the same time, in one legislative package.

The bill ought to be complemented by a campaign funded by civil rights and LGBT+ NGOs and supportive political parties, arguing for equality and fair treatment for all as well as focusing on the fact that by legalizing same-sex adoption, a great number of children in care homes or orphanages may find a loving family — an objective easily put into the context of supporting families and a “family-friendly Hungary”.

These changes would only require a simple majority in parliament and no constitutional amendment, nonetheless, they are likely to be challenged politically and legally and be met with opposition from conservative parties and activist groups. Yet, if polls are to be believed, a majority of Hungarians are at least persuadable regarding this issue.

What the most long-term goal would be is the altering of the Basic Law, requiring a supermajority, to remove the aforementioned stipulations on family and sexual and gender identity. Such step would open the gateway for marriage equality in Hungary (and the abolition of registered partnerships), which is deemed more difficult through the political path and not the courts, as exemplified in Slovenia where the introduction of same-sex marriage was defeated twice on referendums in 2012 and 2015, but was finally legalized in 2022 after the ruling of the Constitutional Court.

Nevertheless, such ruling in Hungary would be quite unlikely due to the government’s overwhelming influence on the judiciary branch, and if such a plebiscite took place in Hungary, it would probably be an uphill battle.

In the meantime, NGOs and political parties supportive of LGBT+ rights ought to keep up their efforts to improve Hungarians’ attitudes toward LGBT+ issues by fighting for fair media representation, appropriate sexual education as well as combatting laws that roll back fundamental rights.

Continue exploring:

We Are People, Not Propaganda: LGBT+ Human Rights in Lithuania

LGBT+ Intergroup as Antidote to National Homophobia, Transphobia