Slovak politicians are full of talks about competitiveness and improving business environment. However, when it comes to action, they oppose even the most trivial and costless improvements.

In Slovakia, a self-employed person, or a company, have to start paying quarterly advanced income tax payments once they reach the EUR 2,500 annual tax threshold. If they reach the EUR 16,600 threshold, they have to start paying advanced income tax every month.

Paying the advanced tax is a bureaucratic burden, since an entrepreneur has to take care of the regular payments. But there is a bigger problem. An entrepreneur has to pay the advanced tax from her/his current income – but the payment size is set according to her/his last year’s tax. This can be a serious obstacle. If you are a small-time entrepreneur who received a big pay for a long-term project in 2018, you have to get ready for hefty advanced tax payments in 2019 – even if your income drops in that year. The state will pay back the difference between the advanced tax payments and the actual tax, but the entrepreneur will get the money back no sooner than in spring of 2020.

The EUR 2,500 threshold strikes us as useless and extremely low, therefore INESS proposed rising the threshold to EUR 10,000. This would mean around 30,000 companies would be excluded from the obligation to pay the advanced tax (but still leaving more than 16,000 subject to the obligation). The Ministry of Economy included this proposal in the draft version of their 2nd “pro-business package”, which they prepared to make doing business in Slovakia easier. Unfortunately, the Ministry of Finance, which has the final say on any measures regarding taxes, refused to pass it. According to the Ministry, such a change would come with budget costs. Had they spent more than 15 seconds thinking about this proposal, they would realize the cost is close to zero.

We are talking here only about cash-flow changes. The general tax obligation for companies would not change, just the flow of payments in time. How much would this cost? We did some rough estimates using the 2016 tax data from the private database Finstat, which collects open data on annual statements of all companies in Slovakia and compared it with the state budget in 2017.

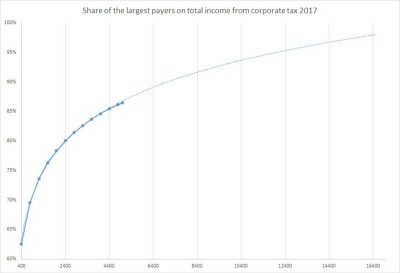

Budgeted corporate tax income (as self-employed persons fall under personal income tax, they were omitted, since no data is available in this regard) for 2017 reached EUR 2.56 billion. The 400 largest payers paid 63% of this sum. The 1,200 largest payers covered 74%, whereas the 5,000 largest paid 86% of all corporate tax income.

These numbers mean that the 30,000 companies which would cease paying advanced tax, have our proposal been accepted, cover only a negligible share of the total corporate tax income. As you can see in the simple chart trend line above, the companies which would remain advanced tax payers even after rising the threshold to EUR 10,000 cover around 97% of the corporate tax income.

Let’s be exceptional pessimists. We introduce two scenarios – one assuming that 5% of corporate tax income would be affected and the second one that 10% of corporate tax income would be affected by the threshold change. This means that Slovak treasury would have to cover EUR 128 million, or EUR 256 million during the year. These millions of euros would not be coming continuously to the state coffers, but would come in one chunk at the end of the year.

This means the state would have to finance the cash-flow gap with 3, 6, and 9-months treasuries. What is the current interest on Slovak government treasuries? Zero percent, sometimes even negative. So rising the threshold would not cost the budget anything.

However, we can suppose the zero interest era will not last forever. Therefore, let us paint two scenarios, one with 0.5% interest rate and another one with 1% interest rate on Slovak government treasuries.

|

Scenarios |

0.5% interest |

1% interest |

|

5% corporate tax income affected |

EUR 240 000 |

EUR 480 000 |

|

10% corporate tax income affected |

EUR 400 000 |

EUR 800 000 |

The most pessimistic scenario – one assuming 10% of corporate tax income – would be affected by rising the threshold, resulting in the state having to pay 1% annual interest on covering the cash flow, would cost EUR 800,000. That’s EUR 800,000 to improve the lives of 30,000 entrepreneurs. In reality, the cost would be even lower, close to zero.

Unfortunately, anything resembling the idea of less taxes is like plague stricken for the Ministry of Finance, which does not want to even consider the subject. But if the Slovak government is not able to improve the business environment even by resorting to the most trivial and virtually costless reforms, how can Slovak entrepreneurs hope for anything better?