In light of record-high price rises, inflation is a term that comes up a lot. For a long period of time, it had a slightly different meaning. Inflation was primarily used to describe a rapid increase in the quantity of money. It is not difficult to understand the link between money and prices.

However, as the word inflation has become so common in everyday life, that link seems to have been forgotten even by economic experts. So how is it that the word which refers to causes now means only consequences?

In the XVII century, an increase in the flow of gold from the New World led to a growing demand for gold storage services. It laid the foundations for the banking business. To protect their gold, people deposited it in a bank and received a paper note (banknote) as a guarantee to later recover their wealth.

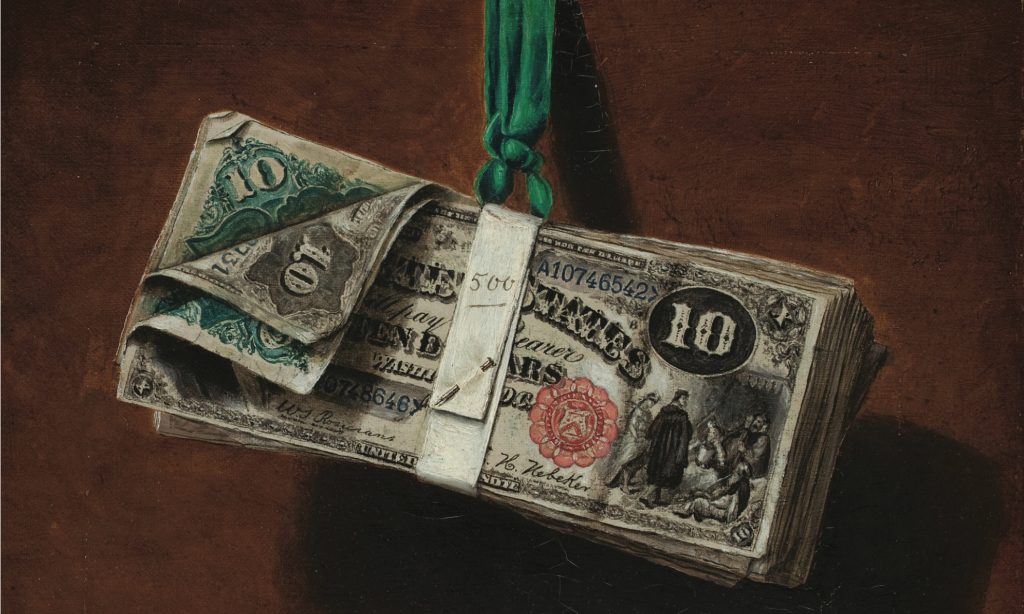

Since the value of these paper notes was more or less the same as the value of gold or silver at the time, in order to sell the gold or buy something with it, all one had to do was simply pass the note on to someone else. Thus, paper notes came to be used as a medium of exchange and accounting, as money.

As the gold storage business expanded, bankers realized that, with enough gold in their vaults, they could take on more liabilities than they could actually meet. After all, only a tiny proportion of customers would come and ask for all their assets at once.

Therefore, banks began to distribute credit. They even offered depositors interest on their holdings so they could attract more reserves. Finally, banks started to issue more and more banknotes, but the amount of gold in their vaults did not increase as fast.

In 1838, Daniel D. Barnard, a member of the US House of Representatives, pointed out that, in his opinion, the regulations at the time allowed banks to hold too little gold in reserve before issuing new notes. As a result, there was a concern that the volume of banknotes would “balloon” and, according to Mr. Barnard, would lead to “an ever-dangerous currency inflation.” Thus the term ‘inflation’ was born.

Webster, the oldest American English dictionary published in 1864, offered a definition of inflation that differs from the one we know today. It says that inflation “applies to currency” and means “an undue expansion or increase due to over-issue.” Thus, inflation originally meant an increase in the quantity of money, leading to its depreciation.

Eventually, the supervision of commercial banks’ reserves was entrusted to the central bank. However, instead of central banks simply supervising the accounts of commercial banks, they became a bank for banks. When there was a shortage of deposits that could be issued on credit, the central bank started to issue loans at the stipulated base interest rates.

However, this did not mean that the concept of inflation changed. For example, when the Federal Reserve Bank was established in the USA in 1913, the publications it published defined inflation as “the process by which additional currency is created through a process other than a proportional increase in the production of goods.” In other words, inflation was still considered to be a factor of price increases but not a synonym of a growth in the prices of products.

However, during the Great Depression (1929-1933), the economic theory advanced by the British economist John M. Keynes became more popular. According to this theory, the level of prices was not determined by the quantity of money but by a high aggregate demand. At that time, the proponents of the quantity theory of money, who talked about a direct relationship between prices and the quantity of money, aligned themselves with Keynesians and started to use the concept of “currency inflation.”

This shift in concepts was reflected in the 1934 version of Webster’s Dictionary. It defined inflation in a broader sense as “a disproportionate and sudden increase in the quantity of money or credit compared with the number of exchange transactions.” It then adds: “according to the law of the quantity theory of money, inflation always leads to a rise in the price level.”

As a result of the controversy over the consequences of an increase in the quantity of money, the concept of inflation became synonymous with the effects of inflation.

The shift in the meaning of the term ‘inflation’ is even better illustrated by the definition used by the Federal Reserve in 1978. It no longer identified the quantity of money as a factor of inflation:

“the most important factors contributing to inflation were the dollar’s depreciation, the substantial increase in labor costs, and adverse weather conditions.”

So, the word that initially accurately defined causes came to be used to refer to consequences.

Words affect and reflect the way in which we see the processes they describe. And while it is unlikely that the original concept of inflation will be restored, we should remind ourselves of its true meaning. It helps us to understand why we encounter a sharp rise in the prices of goods. Although the term ‘inflation’ now is only used to refer to the consequences of monetary policy, namely price rises, the ‘printing’ of money during the pandemic reminded us of what happens when money is inflated too much.

Written by Leonardas Marcinkevičius.

This article was originally published by IQ.

Continue exploring:

Sound Money Is Scarce Money. LFMI Opens Global Money Week in Lithuania

High Inflation in Poland Is Caused by Monetary Policy Council