2015, Paris. For a moment it seemed as if we have finally reached the last step in our quest to combat climate change. And why wouldn’t we feel that way?

The Paris Agreement was and is the only climate accord to date, which is a legally binding document, encompassing 196 countries with – somewhat – clear milestones to reach the desirable outcome: that is, limit global warming to well below 2, preferably 1,5 degrees Celsius, compared to pre-industrial levels.

It is not, however the only agreement nor the latest. But few could question its importance, even after the US withdrawal in 2020 under Trump. It wasn’t even the first time the American government felt like leaving.

“The Kyoto Protocol, adopted in 1997 and entered into force in 2005, was the first legally binding climate treaty. It required developed countries to reduce emissions by an average of 5 percent below 1990 levels and established a system to monitor countries’ progress. But the treaty did not compel developing countries, including major carbon emitters China and India, to take action. The United States signed the agreement in 1998 but never ratified it and later withdrew its signature.”[1]

For a more in-depth overview on the timeline of climate agreements, I advise visiting the following website.

COP26

As I have already said, neither Kyoto nor Paris were the only ones in a long list of climate talks, agreements and failed constructions. As of 2021, the Paris Agreement is the single most important of them, but this might change in the near future. COP26 is due this November, after being postponed due to the coronavirus pandemic.

“COP stands for Conference of the Parties. Parties are the signatories of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) – a treaty agreed in 1994 which has 197 Parties (196 countries and the EU). The 2021 conference, hosted by the UK, together with our partners Italy, in Glasgow, will be the 26th meeting of the Parties, which is why it’s called COP26. United Nations climate change conferences are among the largest international meetings in the world. The negotiations between governments are complex and involve officials from every country in the world as well as representatives from civil society and the global news media.”[2]

The COP26 has ambitious goals: reach net zero emissions by mid-century and keep global warming under 1.5 °C; it seeks to protect local communities and natural habitats; mobilise finance and raise $100bn every year to aid developing countries; finish and implement the Paris Rulebook. These goals need the cooperation of every Party (signatory) and even more – international firms, local businesses and civilians all have a part to play in this battle. There are certain targets and “tools”:

| Mitigation | reach net zero by mid-century, keep warming under 1.5 °C· update NDC’s for 2030 (emission targets)· phase out coal, ban financing for new coal plants

· expand the electric car market |

| Adaptation | prepare local communities, make them more resilient· protect vulnerable communities· Adaptation Action Coalition (intergovernmental alliance) |

| Finance | mobilise global finance, especially the private sector· reach a yearly goal of $100bn in aid for developing countries· financial decisions must calculate with their impact on the climate |

| Collaboration | the UN Climate Talks are consensus based, every opinion counts, every Party matters· finalise the Paris Rulebook· deliver on their promise to combat climate change |

And while these all seem rather inherently good and they must be achieved, sometimes reality differs from the political agenda, however advocable. The plan to phase out coal is a major aspect of the European Union’s own targets – part of the ’Fit for 55’ strategy –, but it faces a largely unspoken obstacle, Germany. We like to think of them as being on the forefront in every aspect, but the economic powerhouse is wrestling with the aftermath of a (in my opinion rushed) nuclear phase out.

Only a decade ago, a quarter of the electricity generated in Germany came from nuclear fission. The government set out to rid itself of it after decades of public opposition and the 2011 Fukushima Daichi meltdown, and while the goal itself is not flawed, they gave into public pressure, rather than planning ahead to maintain energy security.

Only last year, they had to install a brand-new coal fired plant, to replace the drop of energy output. And with the Nordstream 2 pipeline finished, there are talks that it plans to replace one fossil fuel with another, until it can fully support itself with renewables. This does not mean Germany is not planning on participating in these commitments – I merely wish to highlight certain discrepancies in this fight. But chasing a quick political win seems to have resulted in prolonged “doublespeak”, where the only prohibited word is nuclear, and everything else can be switched around as needed.

Another ’problem’ brewing is the pledge to developing countries. The amount is $100bn – and according to the UN, until 2019 only $79.6bn has been raised. It’s a big difference, and the biggest laggards are the US and Italy of the G7 group. In his UN speech, President Biden said he would go further, while Prime Minister Boris Johnson reminded Parties of the challenge to raise this amount. Other rich countries also failed to reach their targets, and even worse, most of this money is in the form of loans – developing/poorer countries are expected to pay it back later.

On the bright side, at the current UN General Assembly, both the US and China highlighted the severity of climate change, and there seemed to be an understanding between them regarding cooperation. To what extent will this play out later, sadly no one knows, and the pledges made here again, will fall short of the $100bn decided 5 years ago. But even then, political will is there – hopefully.

The Fault in the System

The most important variable in this whole equation is cooperation. The Paris Agreement and the COP26 guide both stress the paramount importance of consensus – if only because the legal framework and operation of the UN. But it cannot be said enough that understanding and help between nations is a huge boost for a global solution.

This opportunity, though, carries with itself an equally large vulnerability. You cannot help but notice that most publications, speeches, scientific papers and documents of any kind regarding this topic mention “only together”, “working with” and the word “we”. This shows that the consensus is on ’Consensus’. And yet, we keep falling short on our goals and targets, while time seems to be running out…

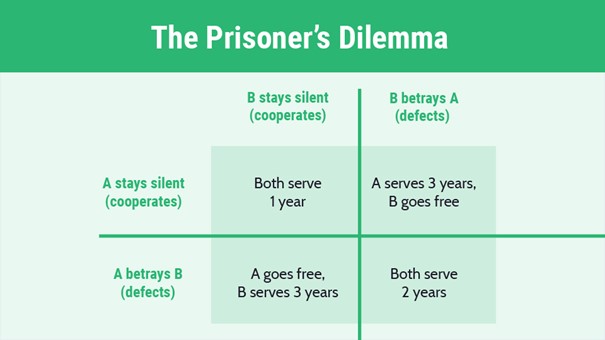

In game theory, there is a famous theoretical question, called the ’Prisoner’s Dilemma’, the basic premise is as follows: two suspects are given a choice – they can either confess about the other’s involvement in a crime thus betraying them, or they remain silent, meaning they cooperate with each other. The two of them are separated and they have no knowledge about the others answer, but they know the rewards for either choice. According to what they say, 4 scenarios are possible:

- A and B cooperates, and they serve 1 year each

- A and B both defect and betray each other, they serve 2 years

- A betrays B, resulting in A going free and B serving 3 years

- A cooperates and B defects, thus A serves 3 years

So what is the best strategy for either? Cooperation would yield the best overall result, 1 year each. But since going free is better than serving 1 year, in both cases defection results in the best personal outcome – thus making betrayal the dominant strategy, since serving 2 years is better than 3. The only way to serve 3 years is to cooperate when the other defects, making cooperation undesirable for a purely rational actor.

Now this payoff matrix can be also used to simulate an agreement between two countries. Cooperation means curbing CO2 emissions, while betrayal would mean keeping up the previous industrial output. With our existing knowledge, we can see how nations would opt for not altering the status quo and wouldn’t want to limit their economic growth for a clearly better overall outcome – as we have seen in the implementation of previous climate agreements.

The U.S. left the Paris Agreement because then President Donald Trump felt like it put a damper on the American economy. The major national economies are also hesitant to curb their growth willingly, while developing countries are justified to feel betrayed, if they are forced to lag behind, because other bigger economies wish to save the planet from the pollution they caused.

There are of course solutions to the Prisoner’s Dilemma, in which cooperation becomes the dominant strategy. One such solution is to repeat the ’game’, so the actors learn of each other’s behaviour – resulting in a so-called iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma. Another solution is the social and political institutions we built in the last couple thousand years. They clearly reward cooperation and penalise defection. Lastly, a behavioural bias towards cooperation has been noticed since the first iteration of this game. Through a kind of natural selection, primitive cultures shunned their members, if they acted against the ’group’.

Another way out is Porter’s Hypothesis: Michael Porter introduced the idea in 1991, that stricter environmental regulations can contribute to higher profits for companies and a cleaner world. In one study, they showed that a Nash-equilibrium could be reached, where both firms opted for the more expensive, but less polluting technology as a dominant strategy– given that the regulations are unyielding. In the conclusion, the authors rightly highlight the limits of the real-world application of this method, but they show that the theoretical framework is there.

Even more important is that without government intervention, the dominant strategy was the old technology – without any incentive to change, companies or even countries can go on without altering their ways, even though they might even see the error in them. This impetus to change can come from the national level, but it can also originate on a much smaller case – the individual.

Brand image and customer loyalty are above all else. Of course, it can be manipulated with clever ads and PR, but still, companies can give into public pressure, such as boycotts. It is possible to catch a polluting corporation in a pincer move, to attack it from above and below – just like with nations. The ’below’ part is somewhat obvious, the voter holds the seed of legitimacy, thus they can exert influence. The ’above’ part can be more elusive perhaps.

World Governments

Immanuel Kant wrote Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch in 1975 and it laid down the base for liberalism in international relations. He divided it into two parts, the Preliminary Articles, and the Three Definitive Articles. The former is to be taken immediately or with deliberate speed: no standing armies, no secret treaties, no independent nation should be inherited, bought etc.; the latter are supposed to be the guarantees for peace – republican constitutions, federation of nations under one law and world citizenship limited to conditions of universal hospitality.

In his mind, republics are more pacific than other forms of government and that a league of nations, functioning as a federation shall unite all, thus eliminating hostilities between nations. Any conflict of interest would be soothed in the framework of the federation.

Of course, liberalism has gone under substantial change since Kant, like neoliberalism and institutionalism for example, which believe similar concepts as neorealism, but draw different conclusions – namely that despite the anarchic state of international relations and the states being the main actors, cooperation can exist and that institutions are capable to supply the necessary “hardware” for global peace.

Other schools of thought, like complex interdependency, argue that the intertwined global market and trade relations make major conflict undesirable. It still leaves room for proxy wars and clandestine actions, but makes world wars even more unlikely.

Now, in the case of environmental regulations and climate accords, there is no concrete theory they seem to follow – states are the main actors, a realist or neoliberal point of view is applied, and legal documents can be instruments of collaboration, just like institutions like the UN, or more precisely UNFCCC. This also leans toward a liberal thought, institutionalism. Of course with news like these, where a nation state can and will go against a “higher power”, it will make us cynical of their usefulness.

Currently, no international organization can actually dictate the home affairs of member states. It can persuade or coerce with deals, but rarely could any of them function as a government regulating a company. We must strive to reign in divergent members nonetheless, or we could fall short of the tasks at hand, previously mentioned. Cooperation is key, but according to game theory, an external factor is needed, to make it a dominant strategy.

Of course, the complexity cannot be fully replicated in the Prisoner’s Dilemma, and real life becomes an iterated version – constant and repeated games give us a chance to learn the other’s strategy, but we keep running into the same problem, lack of serious effort. That’s why an external influence seems essential.

Realist theory says that nations are the ultimate players of international relations, but since the end of the Great War, we have seen gradual acceptance of liberal values, thanks to leaders like Woodrow Wilson, or the Fathers of Europe, after WW2 – Alcide de Gasperi, Jean Monnet, Robert Schuman and Paul-Henri Spaak. They were the right people at the right place and time. The collective experience of the horrors of the war gave them and the people of Europe such drive, that the Old Continent stepped into an unprecedented era of peace and prosperity.

Without the United States, it would have been near impossible – the Cold War and the European Integration showed that neither realism nor liberalism as they were, could understand the World completely. The fall of the Soviet Union, the War on Terror, the illiberal backsliding of certain member states might make us think liberalism has failed since, but with the ever-growing influence of the EU institutions in the sui generis entity, there seems to be a possibility of a powerful enough block, that could push against heavyweights like the US, China, and India.

I used the words ’powerful enough’ and ’push against’… The current state of climate talks feels more like a game of chess, rather than a global partnership. I took the framework of the Prisoner’s Dilemma – a rather realist modus operandi, even though I used it in the context of the largest ’liberal’ organization, the United Nations. Global Warming is something unprecedented, while well documented.

We have known of it for the last couple decades, but we’re yet to see real answers. We keep hearing about ’the last moment to save ourselves’, yet our leaders seem to stand in one place. More and more people realise we must do something, yet we buy the same products, leading to no pressure on companies to change.

Earlier I mentioned a ’two-pronged attack’ on nations, from the voters and international organizations. I would like to add a third – from within. It is up to us, to feel the need of a new way, to make our environment a priority. Our institutions are made up of individuals, so the only way to really bring about change is to give ourselves a brand-new perspective.

With this altered mindset, the democratic process has a chance to channel this into governments and into key decisionmaker’s seats. And liberal theory, with its emphasis on the individual and global partnerships, has an opportunity, to bring us together in a common goal. It’s not the only answer, but if we keep walling ourselves off from deeper collaboration, we won’t see the opportunities it could bring us. It’s in our best interest to find a working solution – fast.

[1] https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/paris-global-climate-change-agreements

[2] https://ukcop26.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/COP26-Explained.pdf