After 25 years, negotiations have concluded on a trade agreement between the European Union and Mercosur, a bloc of South American countries. It aims to significantly liberalize trade between the two regions by eliminating tariffs on 91% of goods, reducing the remaining ones, and removing non-tariff barriers. Moreover, according to the agreement, European sanitary and phytosanitary standards will apply to South American products if they are to be admitted to the EU market. In addition, a key component of the deal will be commitments stemming from the Paris Agreement.

If implemented, the agreement will enable free trade among countries with a combined population of 800 million, creating an opportunity to counteract slowbalization and the global trend of markets closing off to foreign competition. Unfortunately, the agreement faces opposition from interest groups led by farmers, as well as from both right-wing and left-wing populists, joined by political leaders such as Donald Tusk and Emmanuel Macron.

The Mercosur agreement is necessary – it will benefit European consumers and businesses. It is also highly relevant in the context of current global tensions, as it would help weaken Chinese influence in South American countries. Given its emphasis on climate commitments, environmental concerns appear overstated. As noted by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), trade agreements that include climate clauses can contribute to global reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. It is from these three perspectives – economic, security, and climate – that the EU-Mercosur agreement will be analyzed here.

Free Trade Benefits All Sides

Economists rarely agree on matters of economic policy. However, there are exceptions to this rule. One of the few topics on which there is near-unanimous agreement among them is international trade: a significant majority believe that free trade brings benefits. At the same time, when economists do agree on something, they are rarely listened to. Loud opposition to free trade arises with almost every new trade agreement. Before discussing the effects of the Mercosur agreement itself, it is worth recalling another case in which similar arguments were raised.

In 2016, European populists and protectionists (in Poland’s case: farmers, the Razem party, and Kukiz’15 party) protested against the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA). CETA was intended to significantly liberalize trade between the European Union and Canada. At that time, there were warnings about the collapse of EU agriculture or Canada dominating Europe. As it turned out, these fears were not confirmed by reality – both sides benefited from the agreement, and some European sectors significantly increased their exports. After five years of the agreement being in force, Polish flour milling exports to Canada rose by 1065%.

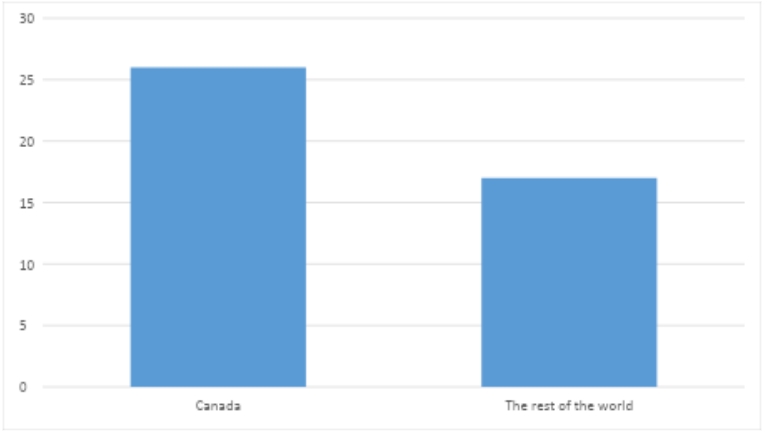

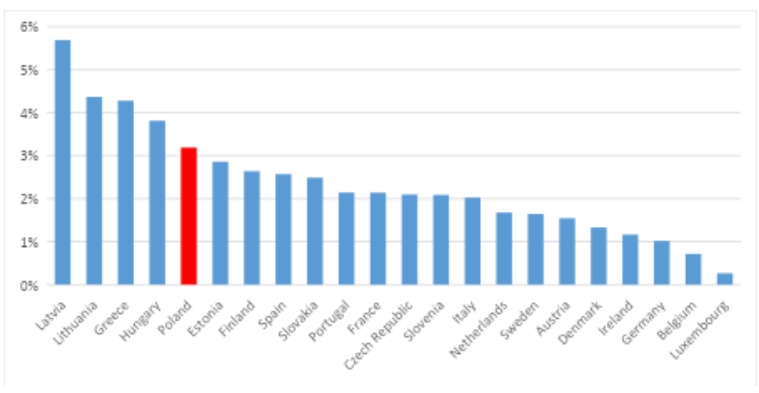

An analysis of the changes over those five years shows that the growth of EU exports to Canada was much faster than to other countries (see Chart 1). Additionally, the agreement increased Europe’s security. Thanks to CETA, cooperation in the area of critical raw materials has grown.

Chart 1. Growth of EU exports in 2016–2021 (in %)

Similar effects can be expected once the EU-Mercosur agreement enters into force. It will stimulate economic growth and save European companies €4 billion by reducing trade barriers. According to economists affiliated with the London School of Economics, the agreement will lead to GDP growth for both partners, by 0.1% for the EU and 0.3% for Mercosur by 2032. Naturally, the benefits will vary across countries and sectors – for instance, the Netherlands is expected to gain 0.03% of GDP by 2035, while Spain may see a 0.23% increase.

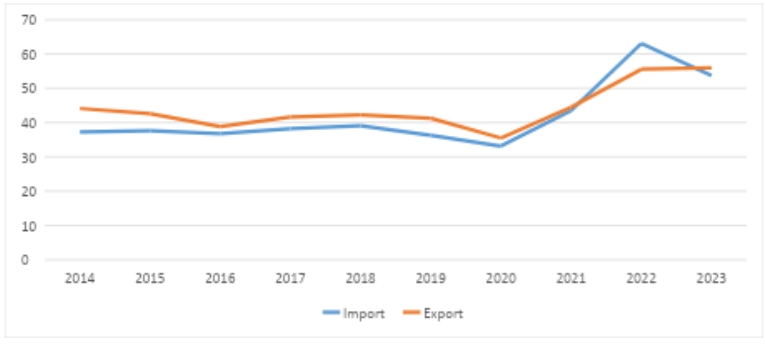

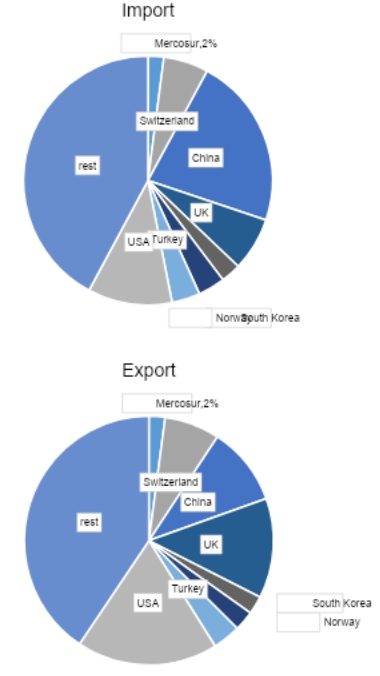

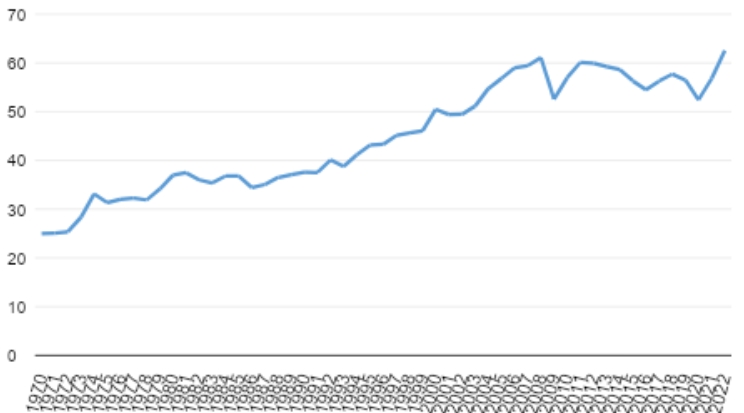

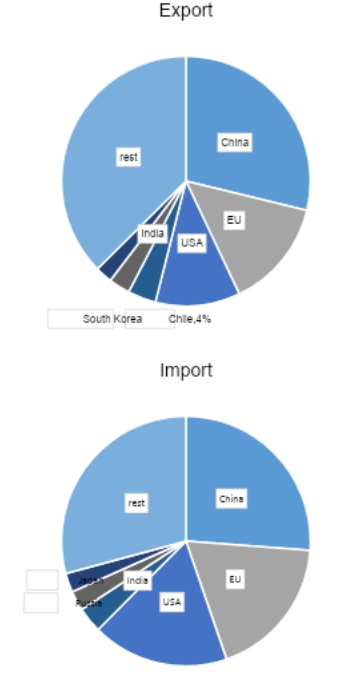

We should also avoid falling into mercantilist fears over the so-called deterioration of the EU’s trade balance – in recent years, the EU has usually run trade surpluses with Mercosur countries (see Chart 2), and these countries currently account for only 2% of the EU’s external trade (see Chart 3). Moreover, contrary to many narratives, trade deficits are not inherently bad. People may intuitively associate a trade deficit with economic loss. The truth, however, is quite the opposite: imports can support economic growth. There is no reason to fear that the agreement will lead to drastic changes, as trade with Mercosur countries can replace trade with more risky partners such as China or unstable African countries.

Chart 2. Trade between EU countries and Mercosur countries from the EU’s perspective (in billion euros)

As with CETA, concerns are being raised about Polish and European agriculture. Populists, farmers, and agriculture ministers from various EU countries want to block the agreement. However, their arguments rely on myths that must be exposed and countered. First, it should be noted that imported agri-food products will have to meet the same sanitary standards as European ones, and the agreement includes climate clauses, which partially level the playing field between South American and European farmers.

Moreover, trade liberalization in the agri-food sector will not be as extensive as in other industries – European farmers will still be “protected” by quotas and tariffs. It is true that European agriculture is in a weaker position than other sectors – it will be difficult to compete with the much cheaper agriculture of South America. At the same time, the agreement with Mercosur countries opens up opportunities to increase exports of processed food products and to reduce livestock farming costs thanks to lower feed prices. In addition, it will allow both partners to capitalize on their comparative advantages, which will improve the quality of life on both continents.

Chart 3. Share of individual countries in EU trade in 2021

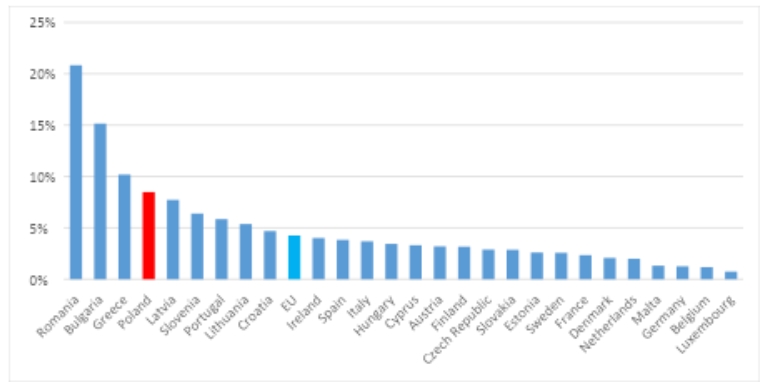

Moreover, in the case of Poland, the agreement could also serve as a stimulus for changes in the labor market and agriculture. Polish agriculture has long struggled with excessive employment and low productivity. Poland ranks fourth in the EU in terms of agricultural employment, with a rate twice as high as the EU average.

Although in 2022, farmers accounted for as much as 8.5% of the employed population, they generated only 3% of GDP. If the EU-Mercosur agreement were indeed to “destroy” Polish agriculture, some of those currently employed in the sector could redirect their labor toward much more productive uses. Instead of maintaining agriculture in an uncompetitive state through subsidies and regulations, politicians at both the national and EU levels should have the courage to state clearly that the sector needs liberalization. As the example of New Zealand shows, liberal reforms in agriculture can significantly improve the sector’s productivity.

Chart 4. Employment in agriculture as a % of total employment in 2022

Chart 5. Value added from agriculture as a % of GDP in 2022

Even if a small portion of the population were to experience minor losses due to the loss of a privileged position, the majority of citizens would still benefit from the agreement. It is also worth noting that the main beneficiaries will be the poorest. Research shows that international trade increases the purchasing power of those in the tenth income percentile the most – in Poland, this can be as much as 61%. The wealthiest also benefit from free trade, though to a lesser extent – in Poland, their purchasing power increases by 23%.

Considering that politicians from the Razem party oppose the agreement, it is worth highlighting one more fact: between 1950 and 2014, free trade increased workers’ leisure time by 19 to 91 hours. If leftists want Poles to work less, instead of proposing populist solutions such as reducing statutory working hours, they should join the front advocating for free trade.

Most importantly, the EU-Mercosur agreement will simply increase choice, both for consumers and producers. Consumers will be able to decide for themselves whether they prefer to buy Polish, French, or perhaps Argentine products. Entrepreneurs, too, will appreciate a broader range of options – in an era of supply chain disruptions, access to alternatives is especially valuable.

In Today’s World, We Need New Trade Agreements

The signing of a trade agreement between the European Union and the Mercosur countries also takes on serious political significance. In an era of slowbalization, a trade agreement connecting two continents offers a chance for economies to begin reopening once again. Chart 6 clearly illustrates the slowdown in the formation of a global economy. Unfortunately, governments are not making it easier to reverse this trend – they avoid signing new trade agreements and instead opt for protectionist interventions.

Chart 6. Value of international trade as a % of global GDP

Dani Rodrik argues that the retreat from free trade is not the result of protectionism, but rather of geopolitics¹⁸. This approach reveals a flawed assumption – free trade can, in fact, be a tool of international relations and great power competition. This is precisely the case with the EU-Mercosur agreement, as noted by numerous analysts. If we want the EU to carry more weight on the international stage in an era of protectionism and growing rivalry between the West and China, signing this agreement is essential. It can provide us with new potential allies, help reduce dependence on China, and, most importantly, expand the range of available supply chains.

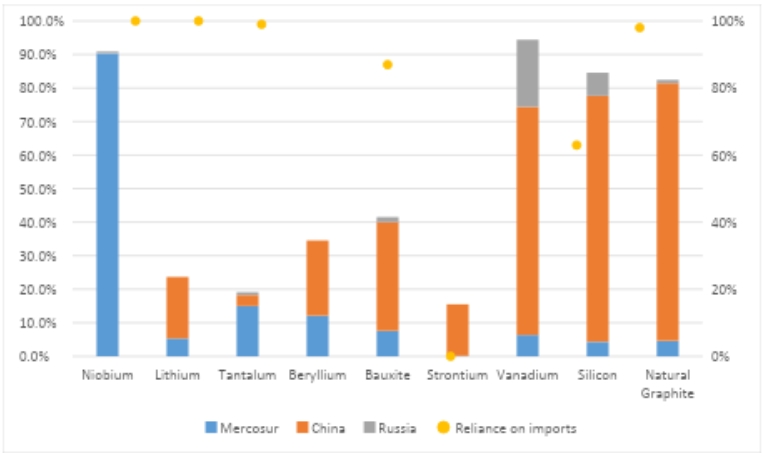

Tyler Cowen has pointed out that liberal cosmopolitans should also care about the security of global supply chains. In his view, they should not immediately fall into neomercantilist dreams of domestic production but must recognize the scale of complexity that cannot be fully understood or centrally planned²¹. From this perspective, the agreement can increase security – we will rely less on single-source products and gain a wider range of suppliers. This aspect of the agreement is particularly important: Mercosur countries have access to many raw materials essential for the energy transition and the development of a modern economy.

Strengthening cooperation with Mercosur can help reduce dependence on China and Russia in favor of politically closer Mercosur countries (see Chart 7). China and Russia are not the only problematic partners – for instance, 36% of the EU’s tantalum usage comes from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, whereas Brazil is the third-largest global producer of this resource. Deepening economic cooperation will help shift at least part of supply chains away from less stable countries to more reliable ones. It should also be remembered that this agreement is an opportunity to increase Europe’s presence in Latin America, both through purely economic relations and through expanded political cooperation. This is an immensely valuable objective, as other Latin American countries can also support Europe’s efforts to reduce reliance on China and diversify critical raw material imports..

Chart 7. Share of global production of selected critical raw materials and the EU’s reliance on imports

Source: FOR’s own analysis based on data from USGS and the European Commission (no EU import data available for beryllium and vanadium)

Deepening cooperation between the European Union and Mercosur countries has another important dimension – beyond purely economic security, it may also enhance political security. Some argue that we are currently witnessing a “Cold War 2.0”. Therefore, Europe needs to expand its list of allies and gain greater independence in shaping its foreign policy. A new Donald Trump presidency could pose serious challenges for the EU, yet closer ties with Mercosur countries would strengthen Europe’s global position. China has used the West’s years of inattention to expand its influence in South America, but after signing the agreement, the EU could gain more prominence in that region (see Chart 8).

Chart 8. Share of selected countries in trade with Mercosur in 2021

This is particularly important because China exports not only products to Latin America, but also its model of governance. As a result, the quality of democracy in Latin American countries has deteriorated. y strengthening economic cooperation—often in key sectors—China is embedding its political apparatus. China’s partners are likely to emulate it not only in domestic policy but also on the international stage. For years, China has been seeking “friends” in South America to support its efforts to build a new world order.

Bailey, Stezhnev, and Voeten developed a measure of “geopolitical distance,” based on ideal point estimations from United Nations voting patterns—the higher the score, the greater the geopolitical distance between countries. According to their analysis, the largest Mercosur countries are already fairly close to China (see Chart 9). Meanwhile, the geopolitical distance between these countries and Germany has increased since 2000. This is yet another argument in favor of deepening EU-Mercosur cooperation. For centuries, economists and thinkers—from Montesquieu and Immanuel Kant to Friedrich Hayek, Ludwig von Mises, and today’s Johan Norberg and Tom Palmer—have seen free trade and globalization as pathways to peace and understanding among nations.

Today, many economists recognize that international trade is shaped by political relationships, yet they devote less attention to how trade itself shapes the global order. Still, some research should give us cause for optimism—greater economic cooperation also strengthens political ties. When countries are more interdependent, they are more likely to act in each other’s interest. Moreover, strengthening the EU’s role in South America could help reverse the anti-democratic changes introduced by China. As it turns out, deeper integration among democracies reinforces democratic systems. The reflections of Tabellini and Magistretti should guide us toward a broad presence in Mercosur countries and the export of cultural and consumer goods, since it is through these that democracy is exported.

Chart 9. Geopolitical distance between country pairs

For the sake of the EU’s security as well, the swift signing of the agreement appears to be a necessity. In today’s world, where the president of the global hegemon—the United States—is a declared protectionist, it is important to present an alternative: free trade. As demonstrated in the previous sections, it will bring benefits to both sides. Moreover, these benefits will not be limited to the economic sphere, but will also extend to political aspects such as security and better institutional quality. Europe simply needs many raw materials, and Mercosur countries appear to be reliable and stable partners compared to other suppliers. Finally, deepening relations will help the people of Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, and Paraguay limit the influence of foreign regimes—chiefly China’s—and live in healthier democracies. This is also a benefit for Europe: in addition to fulfilling humanitarian goals, it will gain democratic partners.

Planet Can Benefit Too

There is yet another dimension in which the EU-Mercosur agreement is unnecessarily demonized: its impact on the climate. Green parties and other left-wing groups oppose the agreement, arguing that it will allegedly harm the climate and destroy the environment. However, the agreement contains climate clauses – countries are obliged to adhere to the Paris Agreement. Some voices claim that these provisions are insufficient and problematic – if a country withdraws from the Paris Agreement, it would be difficult to hold it accountable.

Given more nuanced factors, such as the prevalence of populism and anti-scientific climate views in South America, the climate change clause should be evaluated ambivalently. On one hand, it commits governments to some extent to take climate-friendly action. On the other hand, it appears insufficient and could benefit from the addition of penalties for non-compliance. Nevertheless, these shortcomings are not a good reason to reject the agreement altogether, but rather to improve it.

What will be the agreement’s impact on climate and greenhouse gas emissions? Opinions are divided. The IPCC report cited earlier points to the varied impact of international trade on emissions and notes that environmental clauses can help reduce them. A recent study found that the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) is likely to cause a significant increase in CO₂ emissions. However, the authors also point to the potential for emissions reduction through technological development.

Nonetheless, they do not address the role of climate and environmental clauses. As it turns out, environmental provisions in regional trade agreements have a statistically significant effect on reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Zakaria Sorgho and Joe Tharakan studied the impact of preferential trade agreements, categorizing clauses into climate-related and other environmental measures. The former directly addresses greenhouse gas emissions, while the latter refers to issues such as biodiversity or water management. They demonstrate that trade agreements with environmental clauses should incorporate climate goals, as this is an effective way to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. According to their calculations, including climate clauses reduces per capita emissions by 1.8% for carbon dioxide, 1.1% for methane, and 2.1% for nitrous oxide.

Before analyzing the forecasts on the agreement’s potential climate impact, it is worth examining the current situation. At present, comparing total emissions of the EU and the Mercosur bloc is difficult – EU emissions are nearly four times higher, despite their population being only about 50% larger than that of Mercosur. In terms of emissions per capita, the European Union and Poland – the enfant terrible of the EU’s climate transition – fare significantly worse than Mercosur countries (see Chart 10).

In Latin American countries, the environmental Kuznets curve may be at play, whereby emissions first increase with economic growth and later decline once a certain income level is surpassed. There are also political factors influencing this pattern – for instance, Brazil’s emissions increased during the presidency of Jair Bolsonaro, who was outspoken in his climate skepticism. There is a risk that Argentina, under President Milei, will follow a similar path. However, there is some consolation in the fact that he will at least be bound by the Paris Agreement and somewhat dependent on EU policy. There is also a reason to support Milei’s ambitious plans to expand nuclear power generation capacity. If anti-climate policies are introduced, this could be a small light at the end of the tunnel.

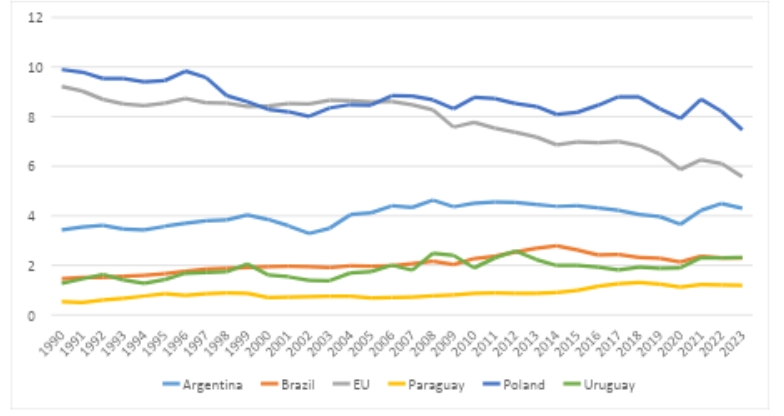

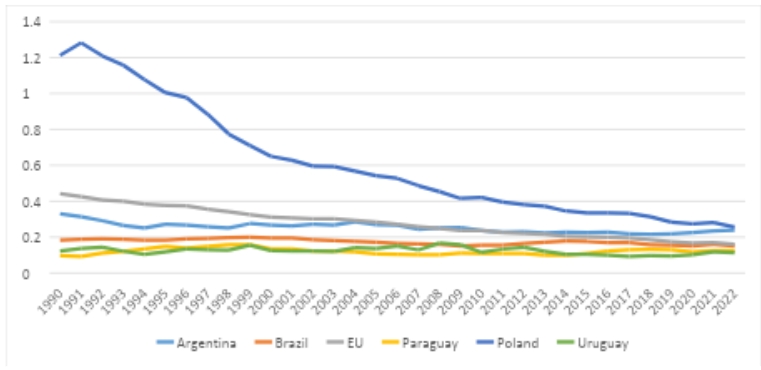

Chart 10. Annual carbon dioxide emissions per capita (in tons)

When examining the relationship between economic growth and greenhouse gas emissions (see Chart 11), one can observe some potential. In Poland (to a large extent) and in the EU, a phenomenon known as “decoupling” has occurred – the separation of economic growth from emissions. However, in the case of Mercosur countries, this phenomenon is not yet as strong – Brazil, in particular, remains a greenhouse gas–intensive economy. Although the trend is downward (over the long term, these countries are reducing the emission intensity of their economies), it is too slow and too unstable.

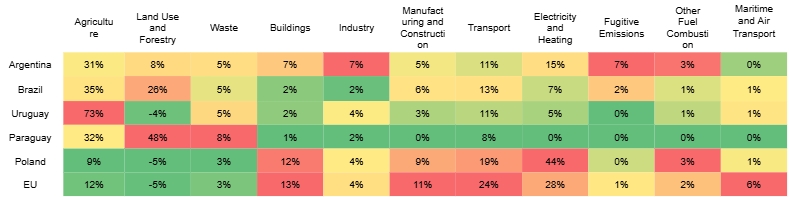

As experience shows, this process can be reversed through policy changes. In this regard, cooperation between the blocs may prove helpful – they can learn from each other and implement green solutions. Individual countries differ significantly in terms of their emissions profiles (see Table 1). This results from both environmental conditions and structural differences between the economies themselves, for example, the greater role of agriculture in South America.

However, this also creates an opportunity to export various solutions that improve performance while being environmentally friendly, such as the use of modern technologies in agriculture. We should also not be overly fearful of the carbon footprint of imports – trade between the EU and China led to the development of green technologies among Chinese exporters. It is reasonable to expect a similar effect again, especially since European consumers increasingly value the environmental impact of the products they purchase. Business actions can simultaneously benefit both consumers’ wallets and the planet.

Chart 11. Relationship between GDP and greenhouse gas emissions (1990 = 100)

Table 1. Share of individual sources of greenhouse gas emissions in 2021

Simulation studies conducted so far indicate a rather mixed impact on the climate. For example, Lattore, Yonezawa, and Olekseyuk show that 16 years after the agreement’s implementation, both regions are projected to emit 0.14% more carbon dioxide. However, the authors remain optimistic – they note that GDP is expected to grow by 0.17%, meaning an improvement in emissions relative to GDP.

As they emphasize, the improvement is global, since emissions would increase by only 0.01%, while GDP would rise by 0.03%. This could be considered a partial success, although they do not examine the impact of EU climate policies and are unable to predict the changes that may occur. Economic growth may lead to innovations that, in the future, contribute to a net-zero economy. A slightly more skeptical view is offered by Mercado Córdova, Jesús Alberto, and Yoonmo Koo – according to their calculations, in the case of extensive trade liberalization, emissions would increase by 0.31%, mainly due to changes in land use.

However, this issue is complex, as land use could expand regardless of the agreement. On the other hand, closer cooperation may also support environmental protection. Economists from the Bank of Spain share a similar perspective. They forecast a slight increase in CO₂ emissions but also note that climate clauses may lead to emission reductions in Mercosur countries. Experts from the London School of Economics likewise argue that the agreement could improve emissions intensity. According to their analysis, this effect would occur in the EU and Paraguay, while emissions intensity is projected to increase in Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay.

It is important to note that climate and environmental impact forecasts are highly uncertain—especially in the Americas, where methane and nitrous oxide account for a large share of greenhouse gas emissions. Many variables can influence how gases are released into the atmosphere. Nonetheless, the agreement between the European Union and Mercosur may strengthen factors responsible for reductions. It will impose obligations on policymakers and businesses, encouraging more environmentally friendly decisions. Given that many studies have shown improvements in emissions intensity, we should remain optimistic. Even if the agreement has flaws today, that is no reason to reject it. If necessary, more ambitious climate targets can always be introduced in the future.

Conclusion

Given the many advantages, it is irresponsible to continue delaying the EU-Mercosur agreement. Even when considering only the economic benefits, we should dismiss the demands of interest groups, particularly farmers. The agreement will benefit citizens of both blocs, especially the poorest. In today’s tense global environment, with the growing conflict between the West and China, increasing Europe’s influence in South America is essential, and this agreement will facilitate that goal.

Furthermore, it will enhance the security of supply chains, particularly for critical raw materials needed by modern economies. From an environmental perspective as well, the creation of such a large free trade area deserves support—projections suggest a decline in emissions intensity relative to GDP. We can also expect green technology development from South American exporters. While political shifts in South America may pose environmental risks, the agreement will allow the EU to more effectively influence the climate policies of Mercosur countries.

In light of this information, it must be stated plainly: signing this agreement is a necessity, and any further delay is shortsighted and harmful to Europe. In an era of widespread protectionism, the creation of such a large free trade area should give momentum to sensible solutions—solutions that revive free trade, from which all participants benefit.

References

[1] Umowa UE-Mercosur gotowa, Komisja Europejska, 6 grudnia 2024, https://poland.representation.ec.europa.eu/news/umowa-ue-mercosur-gotowa-2024-12-06_pl.

[2] A. Słojewska, Mercosur jest gospodarczą i geopolityczną szansą dla Unii Europejskiej, Rzeczpospolita, December 9, 2024, https://www.rp.pl/komentarze/art41553101-anna-slojewska-mercosur-jest-gospodarcza-i-geopolityczna-szansa-dla-unii-europejskiej; K. Paqué, More geopolitics and less protectionism, Friedrich Naumann Foundation For Freedom, April 9, 2024, https://www.freiheit.org/argentinien-and-paraguay/more-geopolitics-and-less-protectionism.

[3] Patt, L. Rajamani, P. Bhandari, A. Ivanova Boncheva, A. Caparrós, K. Djemouai, I. Kubota, J. Peel, A.P. Sari, D.F. Sprinz, J. Wettestad, 2022: International cooperation, w: P.R. Shukla, J. Skea, R. Slade, A. Al Khourdajie, R. van Diemen, D. McCollum, M. Pathak, S. Some, P. Vyas, R. Fradera, M. Belkacemi, A. Hasija, G. Lisboa, S. Luz, J. Malley (red.), Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, New York 2022.

[4] Free Trade, Kent A. Clark Center for Global Markets, March 13, 2012, https://www.kentclarkcenter.org/surveys/free-trade/.

[5] Factsheet: EU-Canada trade agreement (CETA), European Commission, https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu/eu-trade-relationships-country-and-region/countries-and-regions/canada/eu-canada-agreement/factsheets-and-guides/factsheet-eu-canada-trade-agreement-ceta_en.

[6] Ibid.

[7] J. Hinz, C. P. Brockhaus, S. Chowdry, H. Mahlkow, V. Thakur, An analysis of the implementation of the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA), European Parliament, November 2023.

[8] Fechner, T. Geijer, R. Luman, EU and Mercosur seal agreement following decades-long negotiations, ING THINK, 6 grudnia 2024, https://think.ing.com/articles/eu-mercosur-deal/.

[9] M. Mendez-Parra, E. Garnizova, D. Baeza Breinbauer, S. Lovo, J. Velut, B. Narayanan, M. Bauer, P. Lamprecht, K. Shadlen, V. Arza, M. Obaya, L. Calabrese, K. Banga, N. Balchin, Sustainability Impact Assessment in Support of the Association Agreement Negotiations between the European Union and Mercosur, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg 2020

[10] Lattore, H. Yonezawa, Z. Olekseyuk, El Impacto Económico del Acuerdo UE-Mercosur en España, Ministerio de Economía, Comercio y Empresa, September 8, 2021.

[11] Smith, Once again: Imports do not subtract from GDP, Noahpinion, 28 września 2024, https://www.noahpinion.blog/p/once-again-imports-do-not-subtract; A. Freytag, P. Levy, The Trade Balance and Winning at Trade, Cato Institute, October 3, 2024, https://www.cato.org/publications/trade-balance-winning-trade.

[12] Crédit Agricole, Czy umowa UE z Mercosur uderzy w polskie rolnictwo?, Kwartalnik Agrobiznesu, winter 2024, s. 9–10, https://static.credit-agricole.pl/asset/a/g/r/agromapa-202412_31458.pdf.

[13] Suraj, Polskie rolnictwo trzeba zaorać, a następnie posypać solą, Obserwator Gospodarczy, July 12, 2023, https://obserwatorgospodarczy.pl/2023/07/12/polskie-rolnictwo-trzeba-zaorac-a-nastepnie-posypac-sola-felieton/; R. Ditrich, Duże zatrudnienie w rolnictwie hamuje rozwój. To również problem Polski, Obserwator Gospodarczy, October 31, 2021, https://obserwatorgospodarczy.pl/2021/10/31/duze-zatrudnienie-w-rolnictwie-hamuje-rozwoj-to-rowniez-problem-polski/.

[14] Best, Freedom to Farm: Lessons from New Zealand, Cato Institute, June 20, 2024, https://www.cato.org/free-society/summer-2024/freedom-farm-lessons-new-zealand.

[15] Fajgelbaum, A. Khandewal, Measuring the Unequal Gains from Trade, „The Quarterly Journal of Economics” 131(3), 2016.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Stanowisko ws. podpisania umowy handlowej UE-Mercosur, Razem, December 5, 2024, https://partiarazem.pl/stanowiska/2024/12/09/stanowisko-ws-podpisania-umowy-handlowej-ue-mercosur.

[18] Velasquez, The Leisure Gains from International Trade, International Monetary Fund, January 19, 2024.

[19] Michnik, Wolna Wigilia – populizm pod choinkę, Komunikat 27/2024, Forum Obywatelskiego Rozwoju, December 6, 2024, https://for.org.pl/2024/12/06/komunikat-for-27-2024-wolna-wigilia-populizm-pod-choinke/.

[20] A. Kose, A. Mulabdic, Global trade has nearly flatlined. Populism is taking a toll on growth, World Bank Blogs, February 22, 2024, https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/voices/global-trade-has-nearly-flatlined-populism-taking-toll-growth.

[21] Słojewska, Mercosur jest gospodarczą i geopolityczną szansą dla Unii Europejskiej; K. Paqué, More geopolitics and less protectionism.

[22] Cowen, Why Liberal Cosmopolitans Should Worry About Supply Chains, „Social Philosophy and Policy” 40(3), 2023.

[23] Demarais, The bigger picture: The case for an EU-Mercosur free trade deal, European Council on Foreign Relations, January 15, 2024, https://ecfr.eu/article/the-bigger-picture-the-case-for-an-eu-mercosur-free-trade-deal/.

[24] European Commission, Critical Raw Materials Resilience: Charting a Path towards greater Security and Sustainability, European Union, September 3, 2020, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0474.

[25] Sierocińska, B. Michalski, Surowce krytyczne Ameryki Łacińskiej i bezpieczeństwo ekonomiczne Unii Europejskiej, Polski Instytut Ekonomiczny, Warszawa 2024; O. Guinea, V. Sharma, European Economic Security and Access to Critical Raw Materials: Trade, Diversification, and the Role of Mercosur, European Centre for International Political Economy, July 2023.

[26] Smith, Sizing up the New Axis, Noahpinion, 31 sierpnia 2024, https://www.noahpinion.blog/p/sizing-up-the-new-axis-3ce.

[27] A. García-Herrero, China’s growing presence in Latin America is a problem for the West, breugel.org, September 28, 2023, https://www.bruegel.org/newsletter/chinas-growing-presence-latin-america-problem-west.

[28] R.C. Berg, H. Ziemer, Exporting Autocracy: China’s Role in Democratic Backsliding in Latin America and the Caribbean, Center for Strategic & International Studies, 15 lutego 2024; K. Piazza, M. Lasco, China’s Role in Democratic Backsliding in Latin America: Mechanisms and Policy Recommendations, Global Americans Working Paper 2, May 24, 2024.

[29] Smith, T. Fallon, The importance of bona fide friendships to international politics: China’s quest for friendships that matter, „Cambridge Review of International Affairs” 37(1), 2024.

[30] Bailey, A. Strezhnev, E. Voeten, Estimating dynamic state preferences from United Nations voting data, „Journal of Conflict Resolution” 61(2), 2017.

[31] T. Palmer, The Moral Case for Globalization, Cato Institute, April 16, 2024, https://www.cato.org/publications/moral-case-globalization.

[32] Catalan, S. Fendoglu, T. Tsuraga, A Gravity Model of Geopolitics and Financial Fragmentation, International Monetary Fund, 13 września 2024; R. Campos, J. Estefania-Flores, D. Fureceri, J. Timini, Geopolitical fragmentation and trade, „Journal of Comparative Economics” 51(4), 2023; C. Bosone, G. Stamato, Beyond borders: how geopolitics is reshaping trade, Working Paper Series No 2960, European Central Bank, 2024.

[33] Kleinman, E. Liu, S. Redding, International Friends and Enemies, „American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics” 16(4), 2024.

[34] Tabellini, G. Magistretti, Economic Integration and the Transmission of Democracy, „The Review of Economic Studies”, 2024.

[35] Dupré, S. Kpenou, Key Insights into the Final EU-Mercosur Agreement, Institut Veblen, December 12, 2024, https://www.veblen-institute.org/Key-Insights-into-the-Final-EU-Mercosur-Agreement.html.

[36] Patt i in., 2022: International cooperation, s. 1499–1501.

[37] The agreement applies to countries in Asia, Australia and Oceania

[38] Tian, Y. Zhang, Y. Li i inni, Regional trade agreement burdens global carbon emissions mitigation, „Nature Communications” 13, 2022.

[39] L. Baghdadi, I. Martinez-Zarzoso, H. Zitouna, Are RTA agreements with environmental provisions reducing emissions?, „Journal of International Economics” 90(2), 2013.

[40] Sorkho, J. Tharakan, Do PTAs with environmental provisions reduce emissions? Assessing the effectiveness of climate-related provisions?, Working Paper 274, Fondation pour les études et recherches sur le développement international, October 2020.

[41] Ibid, page 29.

[42] Nugent, Argentina chooses US investor to spur nuclear-powered AI dream, Financial Times, December 21, 2024, https://www.ft.com/content/6e0ad76b-02e8-447d-afe1-da41be52d708.

[43] Liu, P. Lv, H. Zhao, Green innovation through trade: The impact of European Union emissions trading scheme on Chinese exporters, „Journal of International Money and Finance” 149, 2024.

[44] Lattore, H. Yonezawa, Z. Olekseyuk, El Impacto Económico del Acuerdo UE-Mercosur en España.

[45] Córdova, J. Alberto, Y. Koo, The environmental effects of the EU-MERCOSUR FTA in induced GHG emissions from LUCC and energy sectors, GTAP Resource #6955,Global Trade Analysis Project, 2023, https://www.gtap.agecon.purdue.edu/resources/res_display.asp?RecordID=6955.

[46] E.M. Susan, C. de Oliveira, J. C. Visentin, B. F. Pavani, P. D. Branco, M. de Maria, R. Loyola, The European Union-Mercosur Free Trade Agreement as a tool for environmentally sustainable land use governance, „Environmental Science & Policy”, 161, 2024.

[47] Campos, M. Suárez-Varela, J. Timini, The EU-MERCOSUR trade agreement and its impact on CO2 emissions, Economic Bulletin, Banco de España, 2022.

[48] Mendez-Parra i in., Sustainability Impact Assessment in Support of the Association Agreement Negotiations between the European Union and Mercosur, s. 88–89.

Written by Mateusz Michnik – Economic Analyst FOR

Continue exploring:

Who Will Win the Polish Presidential Election? with Adam Jasser [PODCAST]