The budget of the European Union could function at half of the proposed cost to EU taxpayers while boosting economic growth, according to a new report, 50:50 for 2020, published in Brussels today.

As European leaders gather in Brussels for the second attempt at agreeing the block’s budget for the next seven years, the author of the report, Lithuanian economist Kaetana Leontjeva, says the EU’s proposals – that include €1.025tn of spending and retaining harmful tariffs and subsidy programmes, such as the Common Agricultural and Fisheries policies, have failed to respond adequately to the economic crisis.

The report, published by the New Direction think tank, proposes a radical alternative budget cutting overall costs by 52%. According to the report, the EU should be funded by a simplified revenue stream based on member states’ economic output, while shifting the focus of spending to trans-European infrastructure and energy networks.

Tom Miers, Director of New Direction, said: “Europe’s leaders are once again wrangling over the EU’s inflated budget. What they really need is to think big – or rather small – and work out what the EU budget is really for. A lot of the money is spent on vested interests and actually harms the EU and its citizens. This study brings some clear thinking on where the budget works, where it doesn’t, and how we could save a lot of money.”

The study’s recommendations include:

- Scrapping duties on trade

- Abandoning proposals for new EU taxes

- Abolishing the Common Agricultural and Fisheries policies

- Reforming competitiveness and cohesion budgets

- Cutting salaries and perks of EU bureaucrats.

50:50 for 2020

How the European Union’s budget could be cut by half

In Brief

The €130bn+ p.a. European Union budget is contested fiercely by member states and various interest groups. But much needed radical thinking by the European Commission has not been forthcoming. This paper examines the theory behind current and proposed revenue raising and expenditure, and proposes an alternative budget based on sound economic principles at half the cost to EU taxpayers.

I. The EU budget – where does it come from and can it be justified?

The EU budget is raised from three main sources: ‘traditional own resources’, mostly trade levies imposed by the EU (13% of the total EU budget), a proportion of VAT raised by the member states (10%), and a further contribution based on their Gross National Income (75%).

- Taxing trade harms both EU consumers and trading partners.

- Income from VAT gives the EU an incentive to promote higher taxes, leads to double taxation and complexity in the EU budget.

- The GNI contribution, by contrast, is proportionate to members’ per capita wealth and gives the EU an incentive to promote growth (including lower taxes).

In addition, the Commission is advocating additional taxes that it could apply directly, including on the financial sector, VAT, various energy taxes and corporation tax. But new EU taxes would likely increase citizens’ dissatisfaction with the EU, would probably add to the overall tax burden, and would reduce tax competition. In particular, there is no evidence that systemic risks in the financial sector can be overcome by a new tax. Instead, it would simply drive business away from the EU.

II. Expenditure – how it is spent and what impact it has

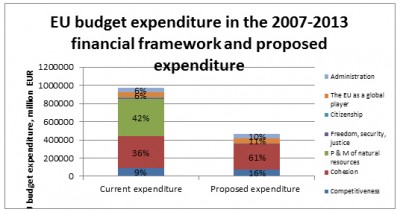

The main areas of EU spending are on competitiveness, cohesion (including regional development), and the preservation of natural resources (including the Common Agricultural and Fisheries policies). The EU also spends money on promoting citizenship, the EU as a global player (foreign policy) and its own administration.

Competitiveness hinges on competition rather than public expenditure, so the EU budget is not attributing the real obstacles to competitiveness. With R&D, for example, the real problem arises when knowledge is not turned into money, but rather low expenditure per se.

- Most cohesion spending is not compatible with competitiveness. It reduces incentives for development, distorts competition, crowds out private investment, increases government spending, encourages corruption and causes inflation.

- By contrast, spending on trans-European transport and energy networks can improve the single market and should remain intact. However, transparency of such projects should improve.

- The CAP does not ensure price stability in agriculture and hurts consumers with higher food prices and taxes.

- Instead of conservation and a sustainable use of marine resources, the CFP results in the depletion of fish stocks.

- Spending on administration has increased by almost a third in this period at a time when member states are trying to control their budgets.

III. Main Recommendations

Much of the EU spending is contradictory in purpose and damaging in outcomes. A streamlined budget would mean a spending cut of 52%, boosting national budgets and economic growth.

- Levies and other duties originating from trade are distortionary and should be gradually removed. The VAT-based resource should be removed, leaving only the GNI-based resource at a lower level. This would be enough to finance the whole budget as envisaged here.

- Introduction of new ‘own resources’ would be counterproductive, making the revenue system more complex and increasing the tax burden. Proposals for new EU taxes should be abandoned.

- EU spending on cohesion and competitiveness should be reformed and should focus primarily on trans-European transport and energy networks, ensuring the transparency of such projects.

- EU spending on preservation and management of natural resources – including the CAP – does not meet its core objectives and should therefore be discontinued.

- The increase in EU spending on administration has to be stopped by cutting the salaries, bonuses and lengthy holidays of the EU’s employees and reducing its overall workforce.