Recent economic shocks and the European Union’s focus on competitiveness have directed the spotlight on the dangers of global value chains. With its unique politics of ‘eastern opening’ and latecomer position to the globalized market economies, Hungary’s strategy in the geopolitical theatre raises many questions.

In the following, I will use an interdisciplinary approach to explain the Hungarian manufacturing industries’ global value chain exposures.

Introduction

Justification: Economic Complexity Index and Domestic Statistics

If we look at the Economic Complexity Index (ECI) and its subcategories for trade, technology, and research for Hungary, we can arrive at a mixed-feelings conclusion. First, the 14th position globally for such a small economy like Hungary proves that the European and Atlantic integration was successful and that the country effectively found its place in the global value chains which is considered key to boosting growth and productivity over time (Farmer & Teytelboym, 2017).

Second, the trade position would imply the extreme exposure of the economy, but the inclusion of the technology (31st) and research (29th) subsets shows an asymmetric and unstable structural layout (OEC, 2023). This exposes what Orbán’s regime tries to hide at all costs: they have steered the country into a middle-income trap and sacrificed the country’s development potential to fuel a minor economic expansion which could have been much greater and sustainable if they had left their ideological constraints behind.

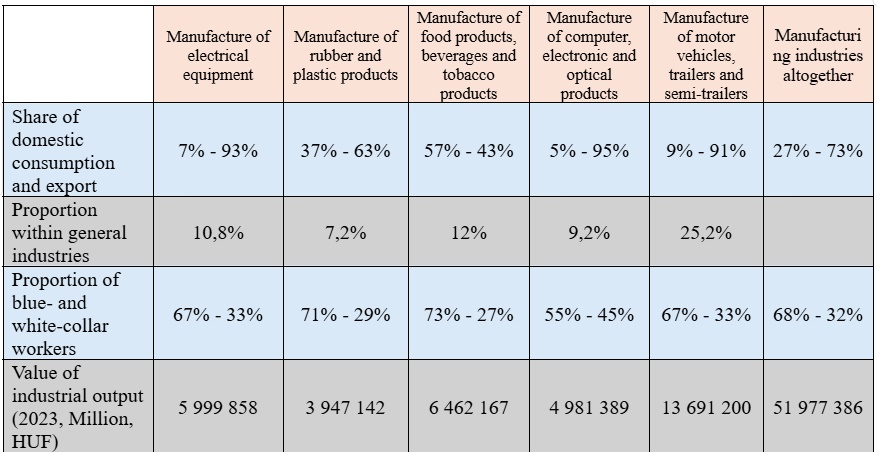

Domestically, it is worth looking at the position of the (general) industry in the Hungarian economy. The industry’s weight in the labor market was 22,8% in 2023 and its portion of the gross added value in the whole economy was 21,2%. Due to the extremely high share (36,1%) of all national economic investments it is safe to say that decision-makers see the sector as a key area (KSH, 2024b).

Secondly, we should take a glance at the statistics highlighting the importance of manufacturing industries. The manufacturing industry accounted for 19,8% of the economy’s gross added value (this is almost equal to the whole portion of the general industry in the whole economy: 21,2 %). Additionally, the manufacturing industries employ around 742.000 people which is 5% of all employed in the economy (KSH, 2024c).

The five observed sub-sectors have been chosen based on their weight within the sector of manufacturing industries (KSH, 2024a) and they are the following: Manufacture of food products, beverages, and tobacco products, Manufacture of rubber and plastic products, Manufacture of computer, electronic and optical products, Manufacture of electrical equipment and Manufacture of motor vehicles, trailers and semi-trailers. The listed have varying positions in the history of Hungary, some have extensive traditions, while some have appeared during socialism or after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. They also show different levels of exposure, employment rates and productivity.

Tendencies of the 1990s and 2000s

After the fall of the Soviet Union and the crumbling of the Iron Curtain, Hungary stepped on the path of transitioning from a centrally planned economy into a free-market economy. The main mechanisms of this process were the privatization of state-owned enterprises, economic liberalization and attraction of foreign direct investments (FDIs).

The openness towards FDIs did not just have the objective of pinning down the high levels of external debt inherited from the socialist regime but also signaled to Western countries that Hungary was planning to be a long-term partner of the core countries. Additionally, FDIs have brought infrastructural developments and channeled the country into the global production chains.

Secondly, privatization -an essential step of market and economic liberalization- has brought bittersweet consequences. Although it led to economic modernization, productivity increase, and stability, it has also caused massive job losses, deepened regional disparities and increased (foreign) dependencies.

European integration is seen as an essential factor in Hungary’s economic development. The early start of the accession process, which was fully realized in 2004 showed a clear economic path for both governments and investors. The EU membership also brought about predictable regulation and a stable political landscape which was perceived as an attractive environment for investments (Dudin, 2016).

While, the aspects introduced above, are the generalization of the most visible tendencies, all five manufacturing industries have experienced these effects to varying extents.

Takeaways and Examples from the WIOD Tables

From the World Input-Output Database, we can extract telling information about international trade (Timmer, 2015). From the magnitude of trade, we can arrive at conclusions on the degree and dimensions of dependencies that Hungary is exposed to.

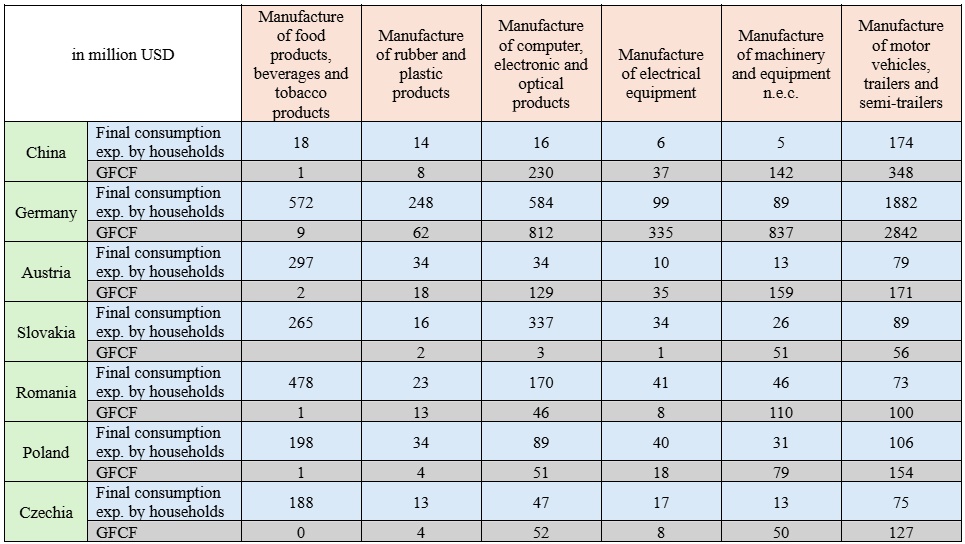

In the following, I will shortly list the most eye-catching vulnerabilities on both the import and export side. The included countries will be Germany and China (the two largest trade partners of Hungary); Romania, Slovakia, and Austria (the top three trade partners of the neighboring countries); and Poland and Czechia (the other two members of the Visegrad Four).

Manufacture of Food Products, Beverages and Tobacco Products

This sector can be considered as a black sheep among the five. Contrary to the others, the majority of the produced goods are sold domestically and the ownership of (agricultural and its manufacturing/processing) firms is mostly Hungarian. The most notable market for food and beverages is Germany with 137 million USD. It is followed by Austria with 43m USD and the Visegrád countries (Poland, Czechia, and Slovakia) with an amplitude of around 40m USD for all three. It is also important to mention the intense dependencies of the ‘crop and animal production related activities’ and neighboring countries’ manufacture of food. The sector does not show any relatively large import exposure.

Manufacture of Rubber and Plastic Products

In the case of the production of rubber and plastic goods, it can be observed that the sector is generally tied to the automotive industries’ relation between countries and sustains a general level of connectedness with surrounding semi-periphery countries. Since rubber and plastic are an essential input material for car-making, their circulation among these economies is explained by the heavy presence of the automotive industry in the Central and Eastern European region.

Manufacture of Computer, Electronic and Optical Products

As seen in the table above, the export rate of the goods produced in the sector is 95% percent, which is extremely high. Additionally, within the realm of import, the Asian countries take a much larger proportion than in any other sector. Here China takes first place with 2206m USD which is channelled into the same optical-electronic-computer product sector and also into the automotive industry. Korea also takes on a large portion of the dependency with 527m USD. Lastly, Germany’s role in the sector is -once again- central. Here, Hungary’s export exposure is 666m if we look at the combined amount of the 4 most important electrical manufacturing subdivisions, while the import exposure is 1125m USD with the corresponding German sub-industry only.

Manufacture of Electrical Equipment

Generally, it can be said that the trade of electrical equipment in the case of import is between 20 and 40 m USD for the Visegrád and neighboring countries; and that Germany’s position is representative of its overall importance with 263 m USD, where China’s role is marginal. The largest market for Hungarian-produced electrical equipment is Germany.

Manufacture of Motor Vehicles, Trailers and Semi-Trailers

The automotive industry, the backbone of the economy, shows extreme exposure. This is not just because of its intensity in the intra-subsector-trade with other countries, but also because of its interconnectedness with other manufacturing industries. The sector’s German import volume is close to 7156 m USD (from 8 branches of German manufacturing industry), while China’s influence is also notable with 755 m USD.

Besides, on the export side, China accumulates only 272 m USD worth of capital flow, while the German market moves 6088m USD. Additionally, on the export side, the economy’s exposure can be considered even more extreme with Austria’s 252, Czechia’s 349, Spain’s 643, Poland’s 199 and Slovakia’s 670 m USD intra-subsector trade volume.

Components of Final Demand: ‘Final Consumption Expenditure by Households’ and ‘Gross Fixed Capital Formation’

Lastly, by examining these two indicators we can conclude the general exposedness and importance of the subsectors. Here, ‘Final consumption expenditure by households’ shows the domestic demand for goods produced within a specific manufacturing industry, it reflects the consumer-driven aspect of national economies. On the other hand, ‘Gross Fixed Capital Formation’ (GFCF) illustrates the intensity of capital investments that are enhancing future production.

Generally, the conclusion can be made that the two largest investors (Germany and China) are more involved in mechanical industries and are willing to invest longer-term, while the surrounding countries have closer connections to agricultural and food-processing industries with especially strong links where production chains connect (mainly for computer-, electronic-, and optical products (Braun, 2020).

Policy-Making Background and Motivations

Semi-Periphery and Dependent-Market Economy Characteristics

The general semi-periphery characteristics within the framework of the world-systems theory are descriptive of Hungary. These cover that the semi-periphery includes traits of both the core and periphery countries (Baylis, 2023). Such nations are dominated by the economic interests of the core but have a relatively vibrant, indigenously owned industrial base. These countries accommodate industries that can no longer function profitably in the core and usually operate with low wages. They regularly show symptoms of inconsistent (political) institutional development, heavy dependencies on exports, and dual economic structures.

Additionally, specific literature within the varieties of capitalism approach (Nölke, 2009) describes dependent market economies (DMEs) as countries that show large dependencies on FDIs and foreign-owned banks, and where intrafirm hierarchies have a large influence on coordination mechanisms. Moreover, in such (semi-periphery) countries, the education and training system receives limited expenditures for further qualifications, and innovation is transferred in an ‘intrafirm’ way, within the proprietary transnational enterprises.

These economies are more dependent on the core countries than other periphery or semi-periphery countries. This thesis receives additional support from the data in the WIOD tables, which show that Hungary’s strongest links are with Germany and China and that the connections between neighboring (semi-periphery) countries are defined by the elements of the production chain possessed by the given neighbor.

Causes

The EU and the Single Market

The most definitive aspect of Hungary’s trade relationships is the European Union membership. Being part of this alliance positioned Hungary in a well-established and efficient economic arena. While the country entered the Single Market well-prepared, it did so without a long-term vision (see later at the middle-income trap).

The country’s membership has opened two large channels of financing and economic support, which have later transformed into the cornerstones of the Hungarian economy (Bottoni, 2023). The cohesion funds offered a cyclical and oven-ready kind of financing which has been realized as infrastructural and regional developments and led to economic growth and convergence. Secondly, the accession has brought the reduction of burdens for the inflow of FDIs.

By now, the Hungarian economy has fully integrated into the Single Market embracing its ups and down-sides. I would highlight two examples of this double-edged sword. The significant FDI inflow has facilitated massive infrastructure developments and elevated the general structure of the economy, but it has also led to increased regional disparities, which has created internal migration. Secondly, the internationalization and harmonization of regulatory burdens have created a pressuring situation for SMEs, who are struggling to open up to the international market.

Ideological Motivations and Foreign Policy

After the win of Fidesz-KDNP in 2010, Viktor Orbán announced the politics of the ‘Eastern Opening’ and the construction of illiberal democracy. The two are different but go hand in hand. The underlying motivation for accelerating trade with Eastern countries (especially China) was not just the reduction of Western economic dependencies, but also to converge the country towards ideologically similar states. This seemed especially necessary because the seeds of disputes between Hungary and EU institutions were not just planted but showed signs of springing.

Orbán did not have to look for long to find his counterparts. Hungary’s eastern orientation fits fully into China’s Belt and Road Initiative and Russia’s efforts to keep European countries in a dependent situation with its fossil fuel and energy supply. The pace of Eastern cooperation has accelerated as the relation between the EU and Hungary has inflamed.

By now the eastern orientation has reached its highest pace. As the EU funds have been brought to a halt because of rule of law investigations and other disputes, the Chinese corporations’ weight increased. The Chinese loans, constructions, and incoming factories are not just valves for pressure relief, which pressure was caused by the lost EU funds, but also an attempt to position Orbán as a heavyweight international actor to win over votes domestically.

Ideological Roots of the Manufacturing Industries’ Support

Domestic factors also influenced the industrial policy decisions of the regime. One of the organizing logics of the administration was that if they could guarantee prosperity and sustain the level of the welfare state, the power-grabbing of the government would be overlooked by the voters. To achieve this, the government believed if they could base the economy on a high employment rate, the (economic and welfare) security perception of the voters could increase and would be stable for a longer period.

The attraction of investments and boosting of manufacturing industries fits into this logic. The government attracted even more labor-intensive factories which required low qualifications. Simultaneously, they have transformed the social support system from a subsidy-based approach to one that uses tax-allowances. This incentivized the population of working age to enter the labor market to receive these supports.

With this, the administration stimulated both the supply and the demand side, therefore the rate of employment, added value, and industrial output all increased in the 2010s, and the program of a ‘work-based economy’ was fulfilled. Of course, this was not solely, the consequence of the Hungarian economic policymaking, but also the general prosperity of the decade. While this boost was visible both macro-economically for analysts and domestically for ordinary voters, the primary motivations of this strategy were quantity-oriented, rather than quality-driven and lacked any long-term planning.

Consequences

The middle-income trap is considered to be the greatest symptom of the absence of this long-term vision. The trap is observable in the case of emerging economies which “experience rapid growth from low-income to middle-income levels—fuelled by cheap labor, basic technology catch-up, and the reallocation of labor and capital from low-productivity sectors like traditional agriculture to export-driven, high productivity manufacturing—is often followed by lower growth” (Larson et al., 2016).

Michael E. Porter and the World Economy Forum have defined clusters of development that can be related to the middle-income trap and help explain the situation in Hungary. The four clusters are: factor-driven; efficiency (investment)-driven; innovation-driven and prosperity-driven economies.

According to the WEF’s Future of Growth Report (WEF, 2024), Hungary is positioned in the “upper-middle income” group which is in the realm of the efficiency-driven development cluster. The main characteristics of such countries are a strong industrial base, dependence on (foreign) investments, export orientation with flexible labor markets, strong infrastructure, and a skilled, but relatively cheap workforce. In such economies, the capital-intensive manufacturing industries are dominant, the production of standardized goods is at the forefront, and the streamlining of these products’ manufacturing is the main target. The technological development happens through the import of innovation.

The question arises: how to break the glass ceiling in such a situation? The path of transitioning from an efficiency-driven economy to an innovation-driven one leads through the enhancement of domestic innovation capacities. In the efficiency-driven cluster, the main driver of competitiveness is the products that have been developed with domestic innovation and those that are marketable internationally. The key to elevating to the next level is the introduction of an effective innovation policy, which is harmonized with the current characteristics of the economy: builds on regional strengths, and coordinated with other targeted policies, like education or industrial programs (Birkner, 2023).

This description naturally leads us back to the existence of global value chains. The limited mobility within the globally interlinked production chains may seem deterministic, but they do offer some room for maneuvering. With an innovation policy that builds on the current value chain positions, the locality of the factories could offer unique connection points to elevate within specific industries.

Here it is important to note that, the current administration sees the educational system as its sole goal is to supply the workforce for the existing economic framework and sees innovation solely as an input for competitiveness enhancement, and not as something inherently valuable.

Nevertheless, tendencies of cooperation between international firms and educational institutions have emerged (Audi’s secondary school in Győr or the MOME – Mercedes collaboration). Unfortunately, these cooperations often have the goal of closing the skill gap (supply of educated workers for the factories) or facilitating brain-drain (highly educated graduates emigrating).

Lastly, I would like to -once again- highlight the dependencies, caused by this economic policy bundle. The Covid-19 pandemic showed how vulnerable these lengthy and complicated supply chains are and with the gradual destabilization of the current geopolitical theatre, we can only expect more shocks to come (Koppány, 2020).

Recent Developments and Expected Trajectories

One of the great signs of the eastern shift was the announcement of EV and battery factories’ arrival in the country. With the attraction of electric vehicle manufacturing, the administration tries to balance out its heavy specialization in internal combustion engines (ICE), while with the batteries it tries to shorten its supply chains for the assembly of EVs (Szalavetz, 2022). This is parallel to the logic of reindustrialization and job creation. The reorganization of the manufacturing industry can be seen as a preparation to channel the workforce from ICE production to EV manufacturing and is also an evident example of an attempt to preserve the current structure of the economy in the long run (Greilinger, 2023).

The shift towards the East is also observable from a Western perspective. The Institut für Europäische Politik (IEP, 2024) has published a paper that raises attention to the distortion of the market environment and warns German firms to be cautious of this tendency. The paper approaches the problem from the direction of the rule of law and points out the Janus-faced characteristic of Hungarian economic policy.

On the one hand, the country attracted FDI through low labor costs and fiscal investment incentives, while on the other hand, a nationalization strategy was realized through massive market interventions (interference in competition law, discrimination of foreign companies, public procurement) to favor Fidesz-affiliated actors. This example illustrates the decreasing trust of Western actors which emerges as a concern for Orbán and his government. This mistrust provides an additional incentive for the administration to look to the east and to further diversify their FDI inflow.

Turning to a domestic aspect, the book of Balázs Orbán: ‘Hussar Cut: The Hungarian Strategy for Connectivity’ can be considered as the general principle of current state organization and as a collection of the regime’s geopolitical expectations. This is not just because there is no other official governmental strategy published, but because Viktor Orban himself includes these thoughts and logic in his speeches and interviews.

The author sees the twilight of Western (US) dominance and expects the global economy to shift towards the east (China). According to the book, the West’s (US and EU) attempt to counter this process is false and Orbán rejects all logic of decoupling and derisking (Orbán, 2023). Interestingly, the openness of the national economy is seen as a setting that should not be changed. Additionally, the risks (and potential losses) of a possible decrease of exposures are seen as larger than the existing dangers of extreme interconnectedness. However, Balazs Orbán includes two very important points that can be considered beams of hope. He extensively discusses the middle-income trap and resilience in a very technical and critical way.

Orbán states that avoiding the middle-income trap is essential to ensure the long-term prosperity of the country. He identifies different types of traps and presents the solution: a state that takes on an active role in coordinating and facilitating the rethinking of existing cooperations. He names seven strategical (loosely interlinked) goals/actions to offset this bad equilibrium. While the list includes elements that are mentioned above, like innovation systems and education, it also embraces the idea of avoiding premature industrialization, which suggests the continuation of the current policy, but at least, it envisions a very moderate and gradual rhythm of shift in economic policy.

The way Orbán is writing about resilience also proves this point. Here the expansion of the -above-mentioned- risk/exposure evaluation becomes central. While his main approach uses mostly institutional aspects and emphasizes the nature of statecraft, he also mentions a more technical element. Namely, that the derisking and decoupling procedures, are not just stripping the nations of the profit of existing interconnectedness but also bring about large amounts of transaction costs. This economic argument underlines the determination of the current administration to continue its deepening integration into Eastern trade relations.

Conclusion

As heavier problems are pressing the incumbent administration’s shoulders, we can conclude that no sudden change of practice is expected regarding industrial policy. While it is noble of the current administration to talk about economic neutrality, the main motifs of their narrative is the justification of the (economic, foreign, and EU) policy decisions they make and not what the expression would naturally mean: reducing dependencies and exposures.

Eventually, I would highlight a few elements that summarize the article’s main points. Although the deepening and widening of manufacturing industries’ portion in the economy was understandable, the lack of preparation for shifting upwards in value chains is not. The weight of ideological motivation in policymaking has grown over the importance of empirical data which leads to distortions and excessive side effects, and externalities. The industrial policy is only motivated by the competitiveness narrative and does not consider the dual shift of green and digital transitions.

With the continuation of the existing practice, the movement of the economy will only continue horizontally (between East and West) and not vertically (reaching higher levels in the value chains), and with that it is predictable that the coming shockwaves are not only going to have larger effects but also distances the country from brighter, safer future.

Bibliography and Additional Sources

Baylis, J., Smith, S., & Owens, P. (2023). The Globalization of World Politics: An Introduction to international relations. Oxford University Press. ISBN: 9780192898142

Birkner Z. (2023). Innovációpolitika és KFI-infrastruktúrák. Akadémiai Kiadó. ISBN: 978 963 454 942 0

Bottoni S., (2023), A hatalom megszállottja – Orbán Viktor Magyarországa, Magyar Hang Könyvek, ISBN 9786150177557

Braun, E. (2020). Kockázatok a Magyar Gazdaság Szerkezetében. Külgazdaság, 64(9–10), 62–89. https://doi.org/10.47630/kulg.2020.64.9-10.62

Bykova, A., Dobrinski, R. N., & Grieveson, R. (2023). Industrial policy for a new growth model: A toolbox for EU-CEE countries. Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.

Cserháti, I., Keresztély, T., & Takács, T. (2021). Versenyképesség és Foglalkoztatás AZ Autóiparban. Köz-Gazdaság, 16(1), 27–38. https://doi.org/10.14267/retp2021.01.04

Dudin, M. N., et al. (2016), Development of Hungary’s Manufacturing Industry in the Conditions of European Integration. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 6(5S), 48–52. Retrieved from https://www.econjournals.com/index.php/ijefi/article/view/2848

OEC. (2023). ECI rankings. The Observatory of Economic Complexity https://oec.world/en/rankings/eci/hs6/hs96?tab=ranking

Greilinger, G. (2023). Hungary’s eastern opening policy as a long-term political-economic strategy. AIES. https://www.aies.at/publikationen/2023/fokus-04.php

Gáspár, T., & Sass, M. (2023). ‘space-time dents’ in global value chains – the Hungarian case. Society and Economy, 45(3), 173–185. https://doi.org/10.1556/204.2023.00020

Gáspár, T., Sass, M., & Koppány, K. (2023). Foreign trade relations of Hungary with China: A global value chain perspective. Society and Economy, 45(3), 229–249. https://doi.org/10.1556/204.2023.00018

IEP. (2024). German Companies in Hungary. To adapt, endure, or engage?. Retrieved from: https://iep-berlin.de/en/projects/future-of-european-integration/democratic-backsliding-hungary-poland/german-companies-in-hungary/

Koppány, K. (2020). A Kínai Koronavírus és a Magyar Gazdaság Kitettsége. Mit mutatnak a Világ Input-Output Táblák? Közgazdasági Szemle, 67(5), 433–455. https://doi.org/10.18414/ksz.2020.5.433

KSH. (2024a). A hat legnagyobb feldolgozóipari alág termelésének volumenváltozása. Ksh Monitor – Ipar, építőipar. https://www.ksh.hu/ksh-monitor/ipar-epitoipar.html

KSH. (2024b). Az ipar helye a nemzetgazdaságban. Helyzetkép | 2023. https://www.ksh.hu/s/helyzetkep-2023/#/kiadvany/ipar/az-ipar-helye-a-nemzetgazdasagban

KSH. (2024c). Munkaerőpiaci folyamatok,. Foglalkoztatottság | Munkaerőpiaci folyamatok. https://www.ksh.hu/s/kiadvanyok/munkaeropiaci-folyamatok/foglalkoztatottsag

Larson, Gregory Michael, et al, (2016). The Middle-Income Trap: Myth or Reality?. World Bank Research and Policy Briefs No. 104230, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3249544

Mealy, P., Farmer, J. D., & Teytelboym, A. (2017). A new interpretation of the economic complexity index. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3075591

Nölke, A., & Vliegenthart, A. (2009). Enlarging the varieties of capitalism: The emergence of dependent market economies in East Central Europe. World Politics, 61(4), 670–702. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0043887109990098

Orbán, B. (2023). Huszárvágás: A konnektivitás magyar stratégiája. MCC Press. ISBN: 9789636440428

Porter, M. E. (2024). The competitive advantage of Nations. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/1990/03/the-competitive-advantage-of-nations

Szalavetz, A. (2022). Transition to electric vehicles in Hungary: A devastating crisis or business as usual? Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 184, 122029. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2022.122029

Timmer, M. P., et al. (2015). “An Illustrated User Guide to the World Input–Output Database: the Case of Global Automotive Production” , Review of International Economics., 23: 575–605

WEF. (2024). The Future of Growth Report 2024. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/publications/the-future-of-growth-report/

Continue exploring:

Despite Challenges, Incomes in Estonia Are Rising

Your “Dream” House – Affordable Living Prospects in Hungary and Budapest [Conference Summary]