The Minister of Family, Labor and Social Policy, Agnieszka Dziemianowicz-Bąk, has once again declared that her ministry is working on a list of professions to be protected from the impact of artificial intelligence (AI), along with regulations that would limit or even ban the use of AI in certain jobs.

This move could turn Poland into an economic backwater and harm Polish citizens, including those working in the professions in question. At the same time, such regulations may contradict other government initiatives aimed at improving business conditions and encouraging the use of AI in the economy.

Despite concerns about the impact of technology on the labor market and society, there is little reason to fear artificial intelligence. Previous technological revolutions did not end in devastation, but in adaptation to new realities and increased general prosperity.

Moreover, the minister is focusing primarily on “creative professions that affect cultural and linguistic heritage.” This is a misguided approach, even from a neo-Luddite perspective — as a report by the Polish Economic Institute has shown, the cultural sector is not particularly threatened by AI. Once again, a left-wing minister demonstrates excessive conservatism — fearful of change, she seeks to block any progress.

Neo-Luddism Is Not Answer

In public narratives about artificial intelligence, people seem to fall into two extremes — overly pessimistic or overly optimistic. In the first, AI is expected to bring destructive consequences and enslave humanity; in the second, it is predicted to lead to a techno-utopia in which everyone lives in extraordinary abundance. Although these positions may appear contradictory, they often rest on the same assumption that AI will make human labor obsolete. We should begin by asking a simple question: Will technological change make human work unnecessary?

During the Industrial Revolution of the 19th century, parts of society, feeling uncertain about the future, began to fear technological progress. That is when the Luddite movement emerged — initially composed of weavers opposing mechanical looms. In later years, this mindset spread to other industries to the extent that “Luddism” came to represent opposition to innovation driven by fear of job loss. These beliefs spread so widely that governments had to introduce laws imposing harsh penalties for destroying machines.

In a way, the Luddites were right. Progress significantly transformed living conditions, creatively destroying the existing order and replacing it with another, centered around new kinds of jobs. This has been the nature of innovation since the dawn of humanity. The invention of agriculture “eliminated” foraging jobs and created farming jobs. The wheel reduced the demand for porters. The printing press decreased the need for manual book copying. Electricity and the Internet also drastically changed the labor market and how society is organized. The consequences of these revolutions were difficult to predict — they certainly had downsides, but the benefits clearly outweighed them. That is why it is worth taking the risk again.

Economists today do not agree on the impact of AI on the labor market. Daron Acemoglu predicts that AI will increase productivity growth by only 0.07 percentage points per year, while Aghion et al., using a similar methodology and empirical literature review, estimate the increase could be as much as 1.24 percentage points annually. Employment research also yields interesting results. One analysis of data from 30 Chinese provinces between 2006 and 2020 found that AI increased employment. Other scholars studying China argue that AI has a negative effect on employment in the short term, but a positive one in the long run. A firm-level study conducted in France between 2017 and 2020 also found that AI contributed to employment growth.

It may still be too early for definitive macro-level forecasts, but micro-level studies show a wide variety of outcomes caused by AI adoption. A consistent trend, however, is increased productivity. Given that we are still at the beginning of this technological revolution — and studies so far point to mostly positive effects, both micro- and macroeconomic — a stance of cautious sanguinity seems warranted. What is more, new jobs directly related to AI are only just emerging. According to the World Economic Forum, by 2030, there will be 170 million new jobs created, while only 92 million will disappear. It is highly likely that many people from younger generations will work in fields that don’t yet exist.

Fears that AI will replace humans may be an overreaction. People tend to underestimate the richness of the human mind. Its value lies not only in intelligence or accumulated knowledge. Hard-to-explain phenomena — even with interdisciplinary research — such as cognition, humor, curiosity, or boredom, may be comparative advantages that humans hold over artificial intelligence. ChatGPT might seem overwhelming when it passes high school exams or university entry tests. But when asked to invent something new, it can face serious challenges — it is a large language model that relies primarily on what already exists.

Gutenberg Press, iPad, and MidJourney

Minister Dziemianowicz-Bąk’s proposal should be rejected on both economic and historical grounds — major technological revolutions are difficult to stop. Her focus on creative professions related to culture and language appears misguided, even from a neo-Luddite perspective. The terminology she uses is vague and could be interpreted as a fear of AI entering the world of culture and the arts — writing, painting, creating, and journalism. This fear has manifested in numerous protests by creative professionals who view the use of AI in their fields negatively. A clear example of this can be seen in the conflict between artists and the creators of MidJourney and Stable Diffusion, who have been accused of copyright infringement and unfair competition, as well as in the reactions to the Off Radio Kraków experiment, in which some journalists were replaced by AI.

In reality, the issue is exaggerated — the Polish Economic Institute studied the exposure of various occupational groups and sectors to AI. It turns out that artistic professions are not high on that list, and the cultural sector as a whole is relatively resistant to AI. The push for special measures in this regard is more a case of technophobia and a desire to protect incumbent artists from new forms of competition. Technological change has always driven artistic transformation. The printing press made manuscript copying obsolete but also significantly boosted reading. The invention of iPods and the development of the internet drastically changed how people consume cultural goods — often reducing their price and lowering barriers for audiences.

We can expect another similar breakthrough in the arts, which may make it weirder, more abstract or absurd — but also more egalitarian and democratic. Nonetheless, the likelihood that AI will fully replace human artists remains low. Cultural economist Tyler Cowen sees a significant role for human creators even after a technological revolution — people do not just want to consume art; they care about the person behind it. As Cowen notes, Taylor Swift’s lyrics could theoretically be written and performed by AI, but her fans are fascinated by her as a person. Luddism has also been criticized by game studies scholar Krzysztof M. Maj, who sees AI as an opportunity to support creators, for example, video game developers will no longer need advanced graphic design skills. As he noted, technology can simplify certain conceptual tasks and allow artists to focus on more creative work.

In light of this, Minister Dziemianowicz-Bąk’s technophobia appears unwarranted. In trying to protect certain groups, she is in practice seeking to block inevitable changes that could benefit humanity. Focusing on creative professions in the context of the AI revolution is unnecessary — the real question should be how to support and adapt to these changes.

AI Regulation Will Harm Economic Growth

The ideas proposed by Minister Dziemianowicz-Bąk appear hasty and ill-considered — we are on the brink of an AI revolution, with new models still developing, and these technologies are here to stay for many years. What is more, artificial intelligence will become the foundation not only of future economies but also of global competition between states. Yet Dziemianowicz-Bąk already wants Poland to withdraw from this race — or at least to slow down.

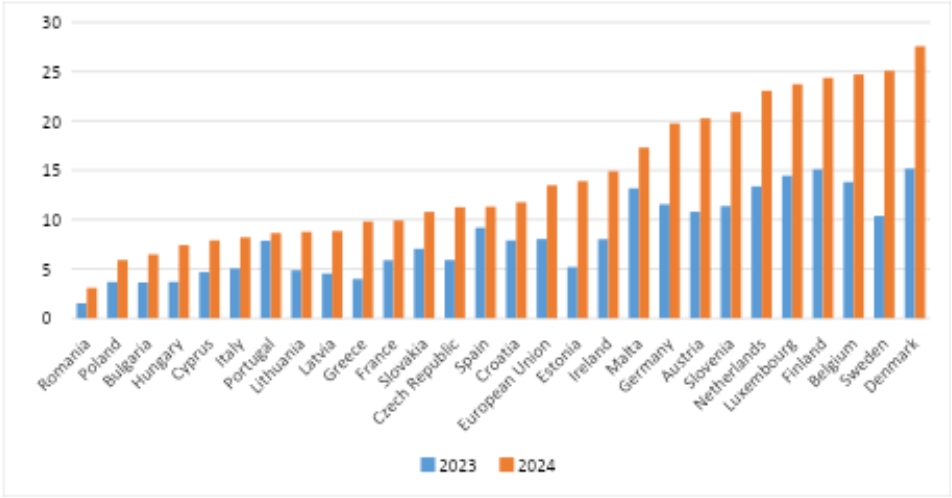

Current research and informed debate, unburdened by technophobic biases, should inspire cautious optimism. Poland may not have the capacity to develop globally dominant AI models, but it can still seize the opportunity offered by technological progress and adapt effectively to artificial intelligence. At the moment, we are lagging behind much of Europe in this area (see Chart 1), and Dziemianowicz-Bąk’s proposals could further worsen the situation. In our conditions, it is crucial to allow entrepreneurs the freedom to use AI in their business operations.

Such decisions are essential — otherwise, we risk withdrawing from technological and economic progress altogether. An aging population will reduce our ability to maintain economic growth. A determined effort to adapt the labor market and the economy as a whole to AI will help offset the negative effects of demographic decline. To achieve this, we must avoid overregulation and the confusion caused by premature political declarations.

Chart 1. Use of Artificial Intelligence in Businesses (in %)

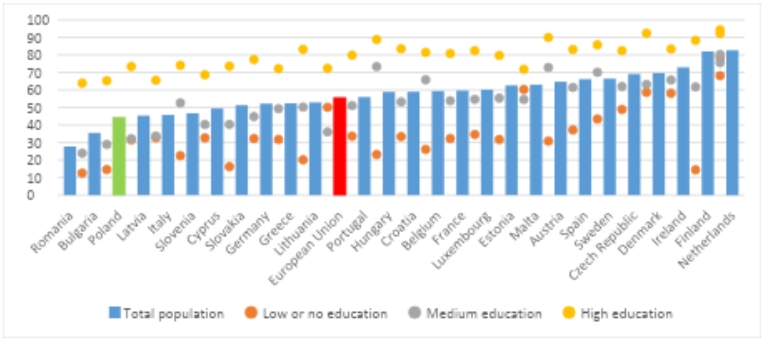

It also seems necessary to adapt education to change and to reduce the competence gap in digital skills. Currently, Poland presents itself low in terms of this knowledge (Chart 2). Artificial intelligence reinforces the need for radical reforms in the education system and increases the need to change the approach to teaching. It seems necessary here to change the curriculum and move away from the memory-based model – in the age of artificial intelligence, the ability to accumulate knowledge is not as useful as critical and analytical thinking.

However, this would require a change in the attitude of teachers, who have little desire to use AI in their teaching work. This transformation should take place in a bottom-up manner – this will allow a variety of solutions to emerge, and teachers themselves should be given training in AI applications.

Chart 2. Percentage of the population with at least basic digital skills

Conclusion

Agnieszka Dziemianowicz-Bąk is jumping the gun with her proposals for new regulations. Artificial intelligence and its business applications are still in the early stages of development, and premature overregulation could weaken the growth potential of the Polish economy. Under current conditions, Poland should embrace the arrival of another technological revolution and adapt accordingly.

Recent research shows that we should not fall into neo-Luddite fears — AI, in fact, supports workers and stimulates economic growth. We should also avoid technophobia in our discussions about culture. In this area, AI can assist artists, lower entry barriers, and diversify artistic expression.

Rather than regulating AI, Poland needs to adapt to change and promote the widespread adoption of artificial intelligence. To achieve this, we must not block its use but instead prioritize digital education and integrate AI into learning from an early age. Such an approach will help close the skills gap and support long-term economic development. Turning our backs on the AI revolution risks making Poland an economic backwater.

References

[1] K. Topolska, Całe branże zabezpieczone przed AI? Ministerstwo pracuje nad zawodami chronionymi, DGP Gazeta Prawna, 9 stycznia 2025, https://www.gazetaprawna.pl/wiadomosci/artykuly/9708230,cale-branze-zabezpieczone-przed-ai-ministerstwo-pracuje-nad-zawodami.html.

[2] Kancelaria Prezesa Rady Ministrów, „Polska. Rok przełomu“ – Premier przedstawił plan gospodarczy na 2025 rok, Serwis Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej, 10 lutego 2024, https://www.gov.pl/web/premier/polska-rok-przelomu–premier-przedstawil-plan-gospodarczy-na-2025-rok.

[3] K. Korgul, J. Witczak, I. Święcicki, AI na polskim rynku pracy, Polski Instytut Ekonomiczny, Warszawa 2024, s. 31–32.

[4] Michnik, Renta wdowia – kosztowna i politycznie motywowana łatka zamiast reformy systemu, Komunikat 21/2024, Forum Obywatelskiego Rozwoju, 3 września 2024, https://for.org.pl/2024/09/03/komunikat-for-21-2024-renta-wdowia-kosztowna-i-politycznie-motywowana-latkazamiast-reformy-systemu/; M. Michnik, Wolna Wigilia – populizm pod choinkę, Komunikat 27/2024, Forum Obywatelskiego Rozwoju, 6 grudnia 2024, https://for.org.pl/2024/12/06/komunikat-for-27-2024-wolna-wigilia-populizm-pod-choinke/.

[5] T. Cowen, Existential risk, AI, and the inevitable turn in human history, Marginal Revolution, 27 marca 2023, https://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2023/03/existential-risk-and-the-turn-in-human-history.html; M. Wolnicki, R. Piasecki, The New Luddite Scare: The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Labor, Capital and Business Competition between US and China, „Journal of Intercultural Management” 11(2), czerwiec 2019.

[6] D. Acemoğlu, The Simple Macroeconomics of AI, Working Paper 32487, National Bureau of Economic Research, maj 2024, https://www.nber.org/papers/w32487.

[7] Aghion, S. Bunel, AI and Growth: where do we stand?, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, czerwiec 2024, https://www.frbsf.org/wp-content/uploads/AI-and-Growth-Aghion-Bunel.pdf.

[8] Y. Shen, X. Zhang, The impact of artificial intelligence on employment: the role of virtual agglomeration, „Humanities and Social Sciences Communications” 11, 2024.

[9] M. Qin, Y. Wan, J. Dou, C.W. Su, Artificial Intelligence: Intensifying or mitigating unemployment?, „Technology in Society” 79, grudzień 2024.

[10] P. Aghion, S. Bunel, X. Jaravel, T. Mikaelsen, A. Roulet, J.E. Søgaard, How Different Uses of AI Shape Labor Demand: Evidence from France, 4 stycznia 2025.

[11] S. Noy, W. Zhang, Experimental evidence on the productivity effects of generative artificial intelligence, „Science” 381(6654), 13 lipca 2023; E. Ide, E. Talamas, Artificial Intelligence in the Knowledge Economy, Proceedings of the 25th ACM Conference on Economics and Computation, 2024.

[12] World Economic Forum, Future of Jobs Report 2025, Gemeva 2025, s. 18.

[13] Franceschelli, M. Musolesi, On the Creativity of Large Language Models, arXiv, 27 marca 2023, https://arxiv.org/abs/2304.00008.

[14] M. Fraser, Przelana czara goryczy. Artyści pozywają twórców Midjourney i Stable Diffusion, CyberDefence24, 17 stycznia 2023, https://cyberdefence24.pl/technologie/przelana-czara-goryczy-artysci-pozywaja-tworcow-midjourney-i-stable-diffusion.

[15] Korgul, J. Witczak, I. Święcicki, AI na polskim rynku pracy, Polski Instytut Ekonomiczny, Warszawa 2024.

[16] Ibidem, s. 31-32.

[17] Cowen, In Praise of Commercial Culture, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA 1998; T. Cowen, Create Your Own Economy: The Path to Prosperity in a Disordered World, Dutton, New York 2009.

[18] T. Cowen, Why everything has changed: the recent revolution in cultural economics, „Journal of Cultural Economics” 32(4), 2008.

[19] T. Cowen, Taylor Swift Will Always Be Bigger Than AI, Bloomberg,11 października 2022, https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2022-10-11/taylor-swift-and-beyonce-will-always-be-bigger-than-ai.

[20] K. Maj, Ajajaj, zgładzi nas A. I. Przeciw luddyzmowi XXI wieku, Open AGH, 2023, https://zasoby.open.agh.edu.pl/zasob/ajajaj-zgladzi-nas-a-i-przeciw-luddyzmowi-xxi-wieku-etee-2023/.

[21] M. Kotlarczyk, Polska potrafi! Jak możemy stać się liderem rewolucji AI w Europie, GDP Gazeta Prawna, 16 października 2024, https://www.gazetaprawna.pl/niemaprzyszloscibezprzedsiebiorczosci/artykuly/9634445,polska-potrafi-jak-mozemy-stac-sie-liderem-rewolucji-ai-w-europie.html.

[22] SpotData, Od kompetencji przemysłowych do technologicznych. Jak Europa Środkowa może wygrać swoją przyszłość w erze AI, 2024, s. 39–41, https://images.pb.pl/static/2024/aB0yesBKBE-od-kompetencji-przemyslowych-do-technologicznych.pdf.

[23] P. Łaniewski, 15 proc. polskich nauczycieli planuje w nauczaniu korzystać ze sztucznej inteligencji, edunews.pl, 29 czerwca 2024, https://www.edunews.pl/badania-i-debaty/komentarze/6697-15-proc-polskich-nauczycieli-planuje-w-nauczaniu-korzystac-ze-sztucznej-inteligencji.

Written by Mateusz Michnik, FOR Economic Analyst

Continue exploring:

Artificial Intelligence: Future Politicians

Responding To Elon Musk: Will Universal Basic Income Save Humanity?