The utopian fantasies projected onto the rapidly evolving cyberspace have given way to the realities of the assertion of age-old human instincts, clothed in new technology. New risks, vulnerabilities and threats are manifested in a complex security environment, where cyber-criminals are carving out their ecological niches, catering not only to the profit motive, but also to new ideologies, and frequently staying one step ahead of the capabilities of their victims or the traditional suppliers of security, the state. Their abilities, in a space which is a great multiplier of power, put them on par with groups or even states and their actions serve to undermine not only the consumer web but also the developing infrastructures of e-governance.

Introduction

The boundless optimism of the Information Age, accompanied by irrational exuberance in markets, as well as technologically savvy evangelists preaching a brighter future through technology, have served to accelerate the mass adoption of cyber technologies whose flaws and vulnerabilities present significant opportunities for random as well as deliberate breakdowns.

Regulators and users have a hard time keeping up with the evolving security landscape, made worse by emergent problems deriving from the interplay between complex systems, organizations and behaviours mediated by the communication afforded by cyber capabilities. The race between protectors and malefactors is always geared towards the latter in such a fluid situation, and the impetuousness of mass adoption and the effervescence in the adoption and diversification of the digital is steadily making things worse.

The easiest element to comprehend is the adversarial relations made possible by the cyber environment. Nations may attack each other’s militaries or legitimate targets through networks, state and non-state actors may perform acts of terrorism, cybercriminals may steal, disrupt or exploit and random virtuosos may sow chaos for personal gratification and promotion.

The harder elements are those which relate to the changes in our societies wrought from evolving cyber connections. Social networks and hierarchies are remade quickly and threaten the social fabric that was once limited by geography, transport and cultural barriers. Notions of privacy and intimacy are also steadily subverted, not just as an adaptation to the new possibilities, but also through cynical encouragement from those who see the profit to be made in this way. Law enforcement and protection are outclassed not just by the act of cyber disruption, but also from the way in which the legal realm has remained forty paces behind the reality of these issues. One should especially highlight the cross-border complexities engendered by the irrelevance of geography in cyber security problems. Jurisdictional issues abound, as well as complexities in trying to establish any sort of regulatory environment, with the apparent conclusion that countries may be “condemned to cooperate” at International levels for appropriate governance of these issues. This is easier said than done.

And, finally, we are forging full speed ahead into a situation where the average person may not be able to wash his clothing without an imprint in the digital environment, creating “valuable” data for some company or another, as well as opportunities for mischief. Driverless cars may be on their way, though one should maintain a level of technical and legal scepticism with regards to their mass adoption. Automated transport ships for global production and supply chains are also coming, and they will be easier to implement and possibly even easier to use to cause mass disruption. Vast amounts of data that we unwittingly create serve to generate an online persona that is less protected than our physical selves have ever been. And, more importantly, all of these changes are taking place in an environment so well connected, that one can scarcely imagine the couplings that may propagate an (un)intentional breakdown throughout the entire system-of-systems. Longing for simpler times is going to become more than a saying or a cliché under these conditions.

A Vulnerability Assessment

Our vulnerability to cyber disruptions of all kinds is staggering and increasing daily. Compounding these issues is the understandable lag between the capacity of organizations to formulate and adopt cyber protection and prevention strategies and adapt them to the rapidly changing environment. One must also underline the fact that cyber protection starts in-house, with each user and organization maintaining their first line of defence, both literally and figuratively, through elements of security culture. This is before one may even start to discuss what the state, the judiciary or some third party or the military may do for you, which is generally limited to responding to issues after the fact or proactively addressing a limited number of threats – particular groups, case files, targets, means of assault (embedded and unresolved vulnerabilities) and so on. There is also a significant asymmetry of information between cyber users and would-be cyber protectors. It is not enough to say that the military is using cyber capabilities to protect its country and its allies when actual system architectures are unique and no single organization can centralize expertise in all of these. An actor called upon to actively and passively protect both industrial control systems, administrative databases, communication lines and underlining infrastructure will do neither of those things correctly.

It is not enough to only run through a list of domains which have undergone a cyber transition of the first order and, sometimes, second or third orders (through the underlying cyber vulnerabilities of processes such as financialization, globalization, conglomeration, decentralization). We need to illustrate the boggling realities of cyber issues:

The first website launched in 1991, while, in 2016, there were 1.2 billion websites (Stevens 2018);

Microsoft believes that online data volumes will be 50 times higher in 2020 compared to 2016 (Boden 2016);

Digital content alone will have expanded from 4 Zettabytes annually to 96 Zettabytes, where a Zettabyte is 1,000 billion Gb (Ibid.);

The Internet of Things will take off, as 2 billion wirelessly communicating smart devices in 2006 will have become 200 billion by 2020, according to Intel Corporation (2017);

The recent craze in wearable devices for fitness or medicine already amounts to 310 million devices sold yearly in 2017 and 500 million in 2021 (Gartner 2017);

The hopeful disappearances of passwords in favour of biometrics have been exaggerated – 300 billion passwords will have to be secured in 2020 (Morgan and Carson 2018);

The 111 billion lines of code added to software each year will make it even more likely that simple human error, unanticipated interactions, planned or unplanned vulnerabilities will increase the risk to networked systems (Kerravala 2017);

90% of cars will be connected to the Internet in some way or another by 2020, up from 2% in 2012, and 20 million cars will be sold yearly with integrated cybersecurity defences on-board (Cybersecurity Ventures 2017);

In 20 years, over 45 trillion sensors will be connected to the World Wide Web, in every imaginable circumstance, from environmental surveillance to social and inside the body of patients or individuals in general;

Lastly, the area of the Internet which is not indexed by search engines and is as such labelled as “dark” is already 5,000-times larger than the visible Internet (Finklea 2017).

These phenomena have been termed the “expanding attack surface of the cyber environment,” which creates new opportunities for mischief and mishaps. Surprisingly, a Cisco study revealed that 40% of manufacturing firms still do not have a strategic approach to cybersecurity (Cybersecurity Ventures 2017).

One must also realize that, as sci-fi author William Gibson said, the future is here, but it is not evenly distributed. Cyber protection issues less penetrate some places or some domains therein. For instance, a less developed country will have found it easier to ensure rapid communications adoption of cyber, while finding it more challenging to upgrade its industrial base so that it may use the latest industrial control systems. This makes it less vulnerable, even as it remains less productive or efficient. At the same time, the lag may very well be recorded in the field of cyber protection, with countries rushing to encourage digitalization without a corresponding awareness of the dangers and the need to invest in security.

Our Brave New Future?

Our growing reliance on the cyber substrate used to coordinate society is also affected by key trends, some of them new and some old.

The first is the still extant democratization of digital skills and knowledge, combined with the low-cost barrier to take digital action. The rapid innovation in the field was engendered by the possibility that young people working “in garages” with few resources, could be able to generate and sustain disruptive technological change. While the maturing of the Internet era enterprises has reduced the extent to which garage firms are viable players, the possibility that motivated and skilled individuals can punch above their weight remains. This applies to hacking as well, where profit, ideology and daredevilry may inspire individuals or small groups to take on and win against many better-resourced organizations. The profound capacity of the cyber system to permit the proliferation of “weaponry” and other forms of pre-made cyber tools, as evidenced by the Wikileaks revelations of the CIA data breaches which saw its arsenal lost online, also raises the stakes in the field.

The second is the rise of “cloud computing.” This is not just the latest buzzword, but also a systemic transformation of staggering proportions, because, in the name of cost and efficiency, it divorces the end user from having to maintain his processing capability or data storage. This centralization makes sense in a world of perfect security, but it compounds the risks associated with the interruption of communication. A computer which is not connected to the Internet may continue to function and be usable. But a simple workstation connected to a centralized processing and data storage hub will be useless in the event of a communications collapse or attack against that critical node. The logic of cyber-attacks also changes, and their scope rises, as the first (and unintentional) cloud computing applications (email services) show, since a single attack may affect, as in the case of the recent Yahoo attacks, over 3 billion users in a single swipe. Any centralization vastly increases the potential payout of an attack or theft, while not necessarily raising its cost, as the consistent and constant revelations of security neglect show.

Thirdly, the ubiquity of cyber raises the number of targets, as well as the number of channels for the propagation of the effects of an attack. It is one thing to fear that one’s own devices may be hacked and damaged, or their data were stolen, and it is another entirely even to imagine the second and third order effects of a cyber-attack on a component for a tightly integrated critical infrastructure system physically spread out all over the world. The cascading disruption is difficult to anticipate, and potential victims find it hard to register the risk. For instance, a hacker may attack the control system of an oil pipeline, forcing a reduction in deliveries, thereby generating an energy crisis with the potential to affect numerous consumers.

Fourthly, the deteriorating state of existing infrastructures and systems leads to several possibilities. The first is that some of these systems may become intertwined with cyber issues in a way that mixes different generations of control systems, creating new vulnerabilities. This is especially prevalent in the energy and industrial sectors, where long-lived assets have gone through several upgrades. The second is that pre-digital systems are either neglected, excluded or replaced with the more efficient and productive systems, leaving a capacity gap which a cyber-attack will highlight. We can compare, for instance, the system of road transport as it is now, before the advent of the mass adoption of driverless cars, with the system that may develop in the future. Several economists have claimed that the success of driverless cars will lead to the rapid reduction of actual driving since insurance companies will incentivize the shift to driverless. At every step in the road to full adoption, the disruptive potential of a cyber-attack increases to the point where, from a relatively resilient system, which could even maintain itself in the context of a breakdown of the traffic light system or GPS navigation, we will have arrived at a totally unworkable system of driverless mass transport.

The Human Factor

Lastly, we must consider the human element of the cyber equation. There is a growing gap between the needs of the cyber security sector and the actual resources, which only a decade-long concerted effort at training, followed by continuing education programs, can cover. The cybersecurity-related employment needs of individual organizations far outweigh the needs of the organizations that create and manage the cyber tools which generate security issues. In the meantime, interesting choices abound for policymakers and various organizations. The tolerance of malicious hackers turned to “whitehats” is one. There is a general debate as to whether captured hackers belong in jail or on the payroll of the organizations they have hacked. Institutions like the military have to reconcile their standards with regards to discipline, indoctrination and leadership culture with the reality of the type of individuals they would have to employ: “The Americans with the best cyber talent may not meet military and appearance standards — they might be out of shape, overweight, have facial tattoos, or some other disqualifying factor” (Barno and Bensahel 2018). It quoted an argument along the lines that “the military needs an entirely new approach to the cyber domain that ‘effectively breaks all the personnel rules and shreds all accepted norms of rank, seniority, and deference that currently characterize what it means to be in the military’”.

If the military does not find enough talent it can mould according to its standards, and it may come to rely on civilian contractors, then it will be faced with many of the same problems that the intelligence agencies faced by outsourcing key data analysis operations, namely security risks related to security culture, ideology and the lack of control over individual contractors (the famous Edward Snowden, at the time of his data theft, was working as a private contractor). The military has other issues, specifically related to chain of command, the ability to move people around and to integrate with other services since cyber is now a domain of warfare. Putting some hackers in uniform may also be necessary “to legitimately and legally conduct offensive cyber operations — the kind of cyber-attacks whose cascading effects could readily inflict grievous harm and death. These cyber warriors need to be subject to the Uniformed Code of Military Justice, so they are held accountable for their actions and legally protected from liability. Putting them in uniform also clearly identifies them as lawful combatants under the Law of Armed Conflict, and, though it may seem quaint, offers them certain rights under the Geneva Conventions” (Ibid.).

The Burden of Cybercrime

While it may seem appealing to debate the issue of hybrid and asymmetric warfare and what cyber-attacks mean from the standpoint of warfare, the more prosaic field of cybercrime holds some of the best examples of the related dangers. It has been estimated that the cost of cybercrime would total 6 trillion dollars in 2020, up from 3 trillion in 2015, which is a staggering amount compared to a world GDP in 2017 of 78 trillion dollars (Cybersecurity Ventures 2017).

According to Harnish (2017), business falls prey to a cyber-attack every 40 seconds, which will drop 19 seconds by 2020 (). A new and important area of the cybercrime business is ransomware, which is a protection racket for the digital age. Ransom payments have reached 1 billion dollars annually, according to the FBI. Global ransomware costs exceeded 5 billion dollars in 2017, marking a 15-fold increase in just two years (Rosenstein 2017). The fact that 1.4 million phishing websites are created every month is also indicative of the breadth of the business.

The whole area of cybercrime, which easily fits into transborder organized crime and is hard to tackle for many of the same jurisdictional reasons, has been steadily professionalizing, thereby mirroring legitimate businesses (Fortinet 2013). Rather than doing everything by oneself, it is possible to contract with providers for any conceivable cybercrime service, including setting up attacks, creating bespoke attack tools, data theft, crashing systems and so on. There is also an organizational structure of crime-as-a-service, with executives, recruiters, infantry and help wanted ads. Meanwhile, new business models proliferate – pay-per-click, pay-per-install, pay-per-purchase, ransomware. One can rent, buy or lease botnets, remote access, exploit kits, crypters, source code. Finally, the money management side of things is also intertwined with white collar crime, which cybercrime often resembles.

According to the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3), the BEC (Business Email Compromise) scam has seen a 13-fold increase in identified exposed losses, worth 3 billion dollars, between 2015 and 2017, while Cisco reports place losses at 5 billion between 2013 and 2016 – “the average size of distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks is 4X larger than what cybercriminals were launching two years ago — and more than 42 percent of DDoS incidents in 2017 exceed a whopping 50Gbps, up from 10 percent of cases in 2015. Cybersecurity Ventures predicts that newly reported zero-day exploits will rise from one-per-week in 2015 to one-per-day by 2021” (Cybersecurity Ventures 2017, p. 13).

Cybercrime is related to other forms of cybersecurity issues. For one, it provides much of the tools, infrastructure, services and knowledge to conduct cyberterrorism operations or easily denied state cyber-attack operations. Avoiding fingerprints and also being able to perform operations without having to insource much of the work are appealing advantages. At the same time, we should remember that the effect of the crime itself is to undermine organizations by creating and cultivating exploits, whether through corruption or cyber-attacks. There is the possibility that, through anti-fragility, an organization hampered in this way may take the required measures to become more resilient, but we have already established that this should be the exception, not the rule.

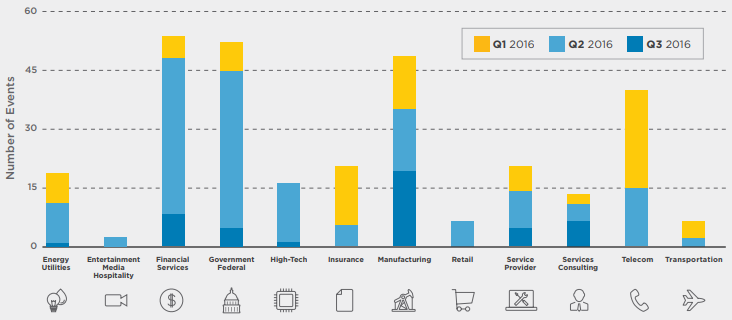

The European cybercrime scene mostly targets the most developed economies, especially companies in manufacturing, finance and telecom. According to the report, in Europe, “mean ‘dwell time’ — the time between compromise and detection — was 469 days, versus a global average of 146 days” (Carpenter and Wyman 2017, p. 13). The links between organizations and government are also not as good – only 12% of intrusions were discovered via notification from a state agency in Europe, as opposed to 53% in the US, which raises the question of whether the number of intrusions is severely undercounted. Figure 1 illustrates the main patterns of cybercriminals targeting European industries in 2016, to the extent that they had been detected. One can observe the concentration on government, finance, manufacturing and telecom, as well as the shifting interest of organized cybercriminals, moving from telecom in Q1 to finance and government in Q2.

Figure 1: Targeted malware detection across Europe during January-September 2016

Source: Carpenter and Wyman (2017).

Source: Carpenter and Wyman (2017).

Conclusion

It is vitally important that the authorities and other actors, such as the military, become proactive with regards to cyber threats, as concerns issues which only they are authorized to handle, such as prosecution, deterrence, regulations and offensive action, though some companies have been known to contract for retaliatory services.

However, companies themselves must take the first steps in their protection, whose main elements are, from a business perspective (Carpenter and Wyman 2017):

-

Seek to quantify cyber risk concerning capital and earnings at risk;

-

Anchor all cyber risk governance through risk appetite;

-

Ensure effectiveness of independent cyber risk oversight using specialized skills;

-

Comprehensively map and test controls, especially for the third-party interactions;

-

Develop and exercise incident management playbooks.

The development of cybercrime is a natural outgrowth of the expanding role of cyberspace in our lives and livelihoods. Along the way, the phenomenon has morphed into an enabler for terrorism and asymmetric warfare elements, contributing to their low traceability and high deniability. There is a dynamic at play where enforcement and protection remain one step behind the cybercriminals, sometimes in different jurisdictions as well, and this problem is compounded by the deficiencies of the security culture of the main body of potential victims (individuals, businesses and state entities). So long as the frontier of the emerging cyber environment keeps expanding outward, creating new interactions and multiplying them between stakeholders, as well as opportunities for those who would speculate the latest trends, this dynamic will remain.

The article was originally published in The Visio Journal 3 (2018)

References

Barno, David, and Nora Bensahel. 2018. “Strategic Outpost Debates a Cyber Corps.” War on the Rocks. February 20th. https://warontherocks.com/2018/02/strategic-outpost-debates-cyber-corps.

Boden, Pete. 2016. “The Emerging Era of Cyber Defense and Cybercrime.” Microsoft Secure, January 10th. https://cloudblogs.microsoft.com/microsoftsecure/2016/01/27/the-emerging-era-of-cyber-defense-and-cybercrime/.

Carpenter, Guy, and Oliver Wyman. 2017. “MMC Cyber Handbook 2018 – Perspectives on the Next Wave of Cyber.” Marsh & McLennan. https://www.mmc.com/content/dam/mmc-web/Global-Risk-Center/Files/mmc-cyber-handbook-2018.pdf.

Cybersecurity Ventures / Herjavec Group. 2017. “2017 Cybercrime Report.” https://cybersecurityventures.com/2015-wp/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/2017-Cybercrime-Report.pdf.

Finklea, Kristin. 2017. “Dark Web.” US Congressional Research Service Report. March 10th. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R44101.pdf.

Fortinet. 2013. “Cybercriminals Today Mirror Legitimate Business Processes (Fortinet Cybercrime Report 2013).” https://cybersafetyunit.com/download/pdf/Cybercrime_Report.pdf.

Gartner. 2017. “Gartner Says Worldwide Wearable Device Sales to Grow 17 Percent in 2017.” Last modified August 24th. https://www.gartner.com/newsroom/id/3790965.

Harnish, Reg. 2017. “What It Means to Have a Culture of Cybersecurity.” Forbes. September 21st. https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbestechcouncil/2017/09/21/what-it-means-to-have-a-culture-of-cybersecurity/#189651c4efd1.

Intel Corporation. 2017. “A Guide to the Internet of Things Infographic.” https://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/internet-of-things/infographics/guide-to-iot.html.

Kerravala, Zeus. 2017. “Cisco to Network Engineers: Get Comfortable with Software. It’s Here to Stay.” Network World. May 25th. https://www.networkworld.com/article/3198474/lan-wan/cisco-to-network-engineers-get-comfortable-with-software-it-s-here-to-stay.html.

Morgan, Steve, and Joseph Carson. 2018. “The World Will Need to Protect 300 Billion Passwords By 2020.” Cybersecurity Ventures. July 4th. https://3erczm2x84t2p8xnj226kmxx-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2018/07/cybersecurity-ventures-thycoti_70778.pdf.

Rosenstein, Rod J. 2017. “Deputy Attorney General Rod J. Rosenstein Delivers Remarks at the Cambridge Cyber Summit (speech).” https://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/deputy-attorney-general-rod-j-rosenstein-delivers-remarks-cambridge-cyber-summit.

Stevens, John. 2018. “Internet Stats and Facts for 2018.” Hosting Facts. July 10th. https://hostingfacts.com/internet-facts-stats-2016/.