Concepts like cyberspace, cyber security, and cyber war are increasingly raised either in media, public discourses or in everyday life. The main reason is likely the high interconnection of cyberspace with the physical space, our daily life. We live a double life, one in the virtual space and the other in the physical one. What is the role of the state in this constellation? Are the characteristics of a state influencing the level of cybersecurity? This article aims to identify some of the factors impacting the cyberspace, present the approaches on cyberspace in the selected countries, effectuate the preliminary analyses of the selected data, and provide the individual interpretation of the results, correlations, and graphic representations.

The cyber domain is evolving, and along with the opportunities, we are witnessing the emergence of new security challenges from the cyberspace. The cyber-attacks can inflict grave risks, spanning from information leaks to actual physical damage. The importance of cyberspace had been recognized by a great number of states, recognizing it as the fourth operational domain. But what is the meaning of cyberspace and what are the factors contributing to cybersecurity? The present comparative research seeks answers to these questions, using various statistical analyses on the People’s Republic of China, Netherlands and Russian Federation.

The first section of the research focuses on depicting the main characteristics of the cyber security strategies of the states, chosen as a reference for the study, while the second section emphasizes the methodology used. The third section discusses the initial interpretation of the results for each country. Finally, the last section compares the results and verifies if there is a general factor that influences the cybersecurity of the selected states. The conclusion confronts the hypothesis set of the study with the results.

The Cyber Security Strategies

The term cyberspace is often defined with cybersecurity, cyber-terrorism and cyber-attacks. Guiora (2017, 17) made a clear distinction between cyber-attacks and cybersecurity. The first refers to the action of harming the state’s critical infrastructure, while the former illustrates the states’ contractual duty to protect the individuals from any attacks. If we are posing the question ‘Cybersecurity for whom?’ Guiora’s answer would be civilians, public infrastructure and overseas assets, public and private.

Many states have recognized the strategic importance of the cyberspace. Thus, they formulated a cybersecurity strategy which varies depending on their security culture and threat perception (Yarger 2008, 43-49). As an example, the Chinese government evokes sovereignty, as stated in the UN Charter: the states have equal sovereignty and the right to choose their path of development without foreign intervention in the internal affairs. China stands for the regulation of the cyberspace, in a form agreed by all the states, to protect the individuals’ rights and interests and to promote the digital economy and the cultural exchange (Shaohui, 2017). China believes that the arms race in the cyberspace is one of the main threats for the international security and stability, contradicting the principle of peaceful use of cyberspace. To defend itself from these threats, China introduced a backup force for the cyberspace (China Copyright and Media, 2016).

The strategy of the Dutch government is concentrated the most on the military dimensions of the cybersecurity, where the Dutch Ministry of Defense is tasked to eliminate the cyber threats and the cyberspace offers an opportunity to increase national security by using the cyber instruments for enhancing military and intelligence capabilities. The Defense Cyber Expertise Centre (DCEC) was created to foster the knowledge development of the cyberspace in cooperation with research institutions and businesses (Dutch Ministry of Defense 2012, 8-16). The civilian dimension of the strategy was designed on a triangle model, involving the individuals, the government and the private sector. The second strategy clarifies the roles and the relations between the actors involved in the cyberspace and the methods used for assuring the cybersecurity (National Coordinator for Security and Counterterrorism 2013, 18).

In the case of the Russian Federation, there is a terminological dissonance involved, as the concept of cyberspace is too narrow to cover all the aspects of cybersecurity. Thus, the concept of information space is employed, which deals with all the technical communication: the internet and other telecommunication networks. Also, because of its trans-national nature, Russia believes that the cyberspace regulation is almost impossible. T. Other priorities are the critical information infrastructure protection, development of the public-private partnership, the increase in the citizens’ digital literacy and strengthening of the international cooperation to formulate a global system of cybersecurity (Federation Council (Russia), 2014).

Methodology

The quest of this research is challenging, but it might help to understand better certain aspects of the cyberspace. This section will unpack research questions, select the variables and set the research hypothesis.

The Theoretical Framework of the Research

Aiming to identify the factors which are influencing the cybersecurity in the People’s Republic of China, Netherlands and Russian Federation, the Personal Freedom Index, the Democracy Index and the ICT Development Index (IDI) are used as independent variables. To illustrate the cybersecurity, the risk of malware infection is used as the dependent variable. The selected states have different national and foreign policies, levels of technology development and organizations responsible for the cybersecurity. They have different perspectives on cyberspace. To identify the factor of cybersecurity, the following hypotheses are tested:

A. The relation between Personal Freedom and the risk of malware infection:

H0: There is no relation between Personal Freedom and the risk of malware infection.

H1: The highest the Personal Freedom is, the highest is the risk of malware infection.

H2: The highest the Personal Freedom is, the lowest it the risk of malware infection.

B. The relation between the democracy index and the risk of malware infection:

H0: There is no relation between the democracy index and the risk of malware infection.

H1: The highest the democracy index is, the highest is the risk of malware infection.

H2: The highest the democracy index is, the lowest it the risk of malware infection.

C. The relation between the ICT Development Index and the risk of malware infection:

H0: There is no relation between the ICT Development Index and the risk of malware infection.

H1: The highest the ICT Development Index is, the highest is the risk of malware infection.

H2: The highest the ICT Development Index is, the lowest it the risk of malware infection.

Malware is a software which has malicious intent or effect. The malware family includes threats like Trojan horses, viruses, worms, adware, backdoor, spyware and others (Aycock 2006, 2). This article focuses only on the web-based attacks (online threats). The figures used to reflect the risk of online threats resulted from the frequency of encountered detection verdicts on users’ machines in each country, by the Kaspersky Lab’s web antivirus. The value illustrates the percentage of users from a particular country who experienced a malware infection (Garnaeva at al., 2015). The risk of malware infection is the dependent variable.

The Personal Freedom Index measures the degree in which individuals enjoy the civil liberties (freedom of speech, religion, and association and assembly). The freedom of expression, which includes control over the Internet Access, is one of the components of the Personal Freedom Index. The use of internet has tremendous importance as it is one of the main instruments to inform, express and interact with other individuals (Vásquez and Porčnik 2017, 9-14).

The Democracy Index measures citizens’ fundamental political freedoms and liberties, the government functioning efficiency, independent media and judiciary system and isolated anomalies (The Economist Intelligence Unit 2017, 52).

The ICT Development Index (IDI) is combining 11 indicators for monitoring the level, the progress, the differences and the development potential of the information and communication technologies (ICTs) in different countries. There are three factors of information and communication technologies development: access, use and skills. Combining these variables, creates an outcome, or an impact, which is the level of ICT development level in a country. The values resulted from combining those indicators reflect the stage of development of the information society (United Nations – ITU 2014, 36-37).

Data Processing, Corroboration, and Analysis

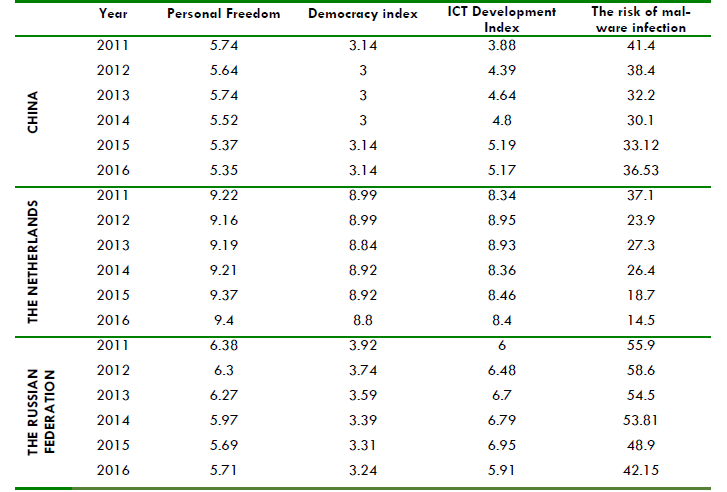

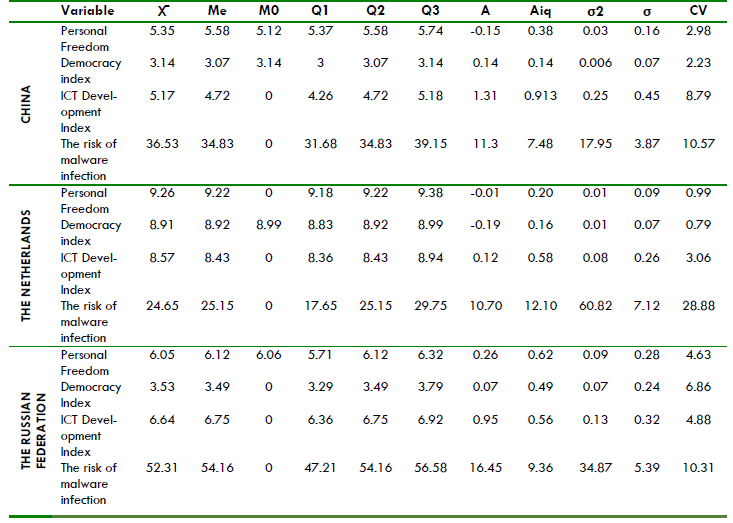

We have selected secondary data, gathered through desk-based research from various sources. The Personal Freedom Index was collected from the Human Freedom Index 2018 (Vásquez and Porčnik 2018, 121-301) a report co-published by the Cato Institute, the Fraser Institute, and the the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom. The Democracy Index was collected from the report issued by the Economist Intelligence Unit (2017, 25-27). The ICT Development Index was collected from different reports for 2011 (ITU 2012, 21), 2012-2013 (ITU 2014, 42), 2014-2015 (ITU 2016, 13) and 2016 (ITU 2017, 31) by the United Nations International Telecommunication Union. Finally, the Risk of Malware Infection was collected from the annual statistics issued by Kaspersky Lab at the for 2011 (Namestnikov, 2012), 2012 (Namestnikov and Maslennikov, 2012), 2013 (Funk and Garnaeva, 2013), 2014 (Garnaeva at al., 2014), 2015 (Garnaeva at al., 2015) and 2016 (Garnaeva at al., 2016) (see Table 1).

Table 1: The People’s Republic of China, the Netherlands and the Russian Federation

Next, the article provides the radiography based on the statistical distribution of the indicators. This model indicates the type of relationship between the variables (see Table 2). China’s cybersecurity level is the lowest among the selected countries. With a low statistical deviation of σ= 3.87, the level of cybersecurity in China is relatively constant in comparison with the other countries, the aspect which is also illustrated by the quartiles. Also, the mean of Me= 34.83 shows that the risk of malware infection has a tendency towards high values, which implies mostly low levels of cybersecurity. The high statistical deviation of σ= 7.12 shows that the Netherlands fluctuant level of cybersecurity and the mean of Me= 22.15 shows that the Risk of Malware Infection tends to oscillate from a relatively low level of cybersecurity (37,1 in 2011) to a high level of cybersecurity (18,7 in 2015).

Next, the article provides the radiography based on the statistical distribution of the indicators. This model indicates the type of relationship between the variables (see Table 2). China’s cybersecurity level is the lowest among the selected countries. With a low statistical deviation of σ= 3.87, the level of cybersecurity in China is relatively constant in comparison with the other countries, the aspect which is also illustrated by the quartiles. Also, the mean of Me= 34.83 shows that the risk of malware infection has a tendency towards high values, which implies mostly low levels of cybersecurity. The high statistical deviation of σ= 7.12 shows that the Netherlands fluctuant level of cybersecurity and the mean of Me= 22.15 shows that the Risk of Malware Infection tends to oscillate from a relatively low level of cybersecurity (37,1 in 2011) to a high level of cybersecurity (18,7 in 2015).

As a result, the interquartile range is the highest among the selected countries. The situation is different in the case of the Russian Federation, where we can identify a low level of cyber security, as the indicators show high levels in the Risk of Malware Infection with a mean of Me= 54.16. The value of the statistic deviation σ= 5.39 mid-range in comparison with the other two countries, which shows that although there have been registered some changes in this respect, they are not significant ones.

Table 2: Statistical Analysis of the Indicators

Interpretation of Measurement Indicators

Interpretation of Measurement Indicators

China, the Netherlands and Russia have different cyber profiles, due to their political culture, security perceptions and objectives in cyberspace. In each case, the correlation of three variables (Personal Freedom, Democracy Index and ICT Development Index) is tested. This study aims to identify the factors that influence the risk of malware infection.

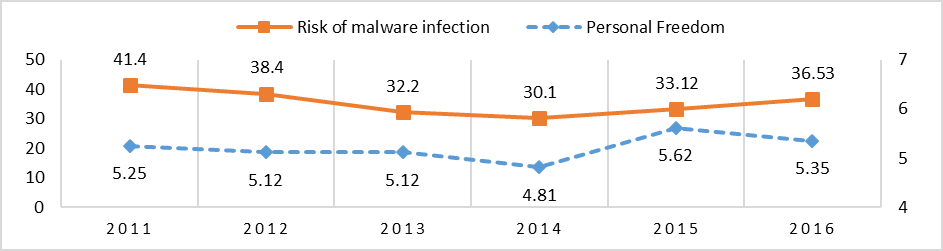

For China, the relation between Personal Freedom (independent variable – I. V.) and Risk of Malware Infection (dependent variable – D. V.) shows a weak positive correlation, with a value for Pearson coefficient of R= 0.31. The influence between those variables is seen in Figure 1, where we observe a decrease in the Risk of Malware Infection when Personal Freedom is decreasing between 2011-2014 and a reverse phenomenon between 2014-2016.

Figure 1: Risk of Malware Infection and Personal Freedom in China, 2011-2016

Sources: Kaspersky Lab; Vásquez and Porčnik, The Human Freedom Index 2018

Sources: Kaspersky Lab; Vásquez and Porčnik, The Human Freedom Index 2018

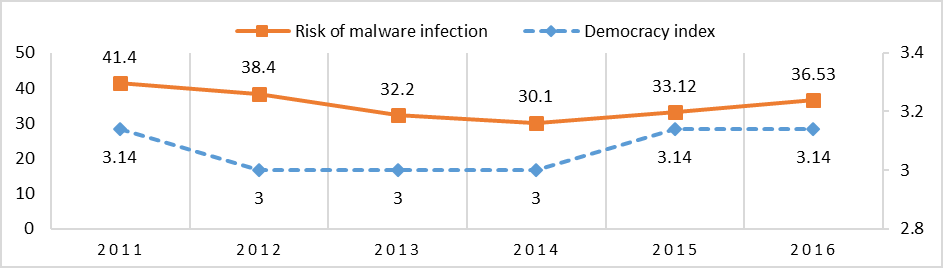

The second set of variables, the Democracy Index (I. V.) and the Risk of Malware Infection (D. V.) are correlated positively as well, with the Pearson coefficient of R= 0.45. The correlation graphic (see Figure 2) shows that the decrease/stagnation of the Democracy Index for the period 2012-2014 leads to a lower Risk of Malware Infection. With the increase of the Democracy Index between 2014-2016, the Risk of Malware Infection also increased.

Figure 2: Risk of Malware Infection and Democracy in China, 2011-2016

Sources: Kaspersky Lab; Economist Intelligence Unit

Sources: Kaspersky Lab; Economist Intelligence Unit

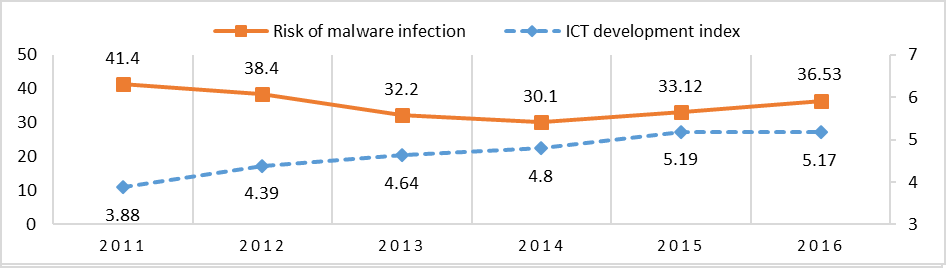

The last set of variables, the ICT Development Index (I. V.) and the Risk of Malware Infection (D. V.) have a strong and negative correlation of R= -0.64 (see Figure 3). One of the reasons why these two variables might not correlate is because the ICT Development Index has a constant growth, while the Risk of Malware Infection tends to variate.

Figure 3: Risk of Malware Infection and ICTs in China, 2011-2016

Sources: Kaspersky Lab; United Nations International Telecommunication Union

Sources: Kaspersky Lab; United Nations International Telecommunication Union

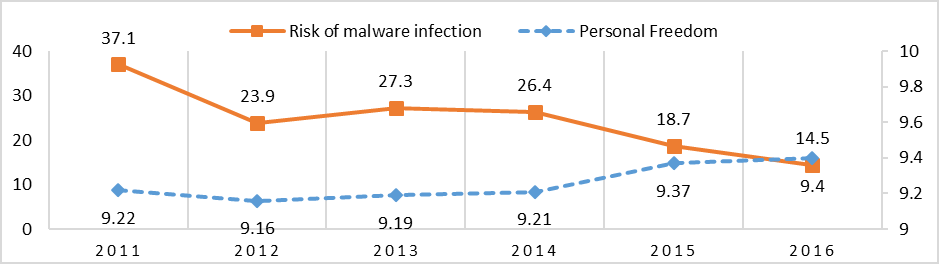

For the Netherlands, the first set of variables, the Personal Freedom (I. V.) and the Risk of Malware Infection (D. V.) indicates a strong and negative correlation of R= 0.-71. Figure 4 indicates a constant growth of the Personal Freedom, while the of Malware Infection has the tendency to decrease, with the exception of 2013, where it shows a growth.

Figure 4: Risk of Malware Infection and Personal Freedom in the Netherlands, 2011-2016

Sources: Kaspersky Lab; Vásquez and Porčnik, The Human Freedom Index 2018

Sources: Kaspersky Lab; Vásquez and Porčnik, The Human Freedom Index 2018

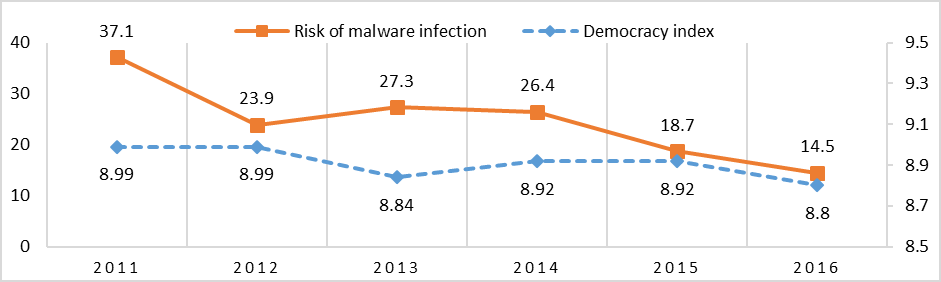

The relation between the Democracy Index (I. V.) and the Risk of Malware Infection (D. V.) shows a strong and positive correlation of R= 0.6. Figure 5 indicates that the Democracy Index is either oscillating or stagnating. The stagnating periods of the Democracy Index between 2011-2012 and 2014-2015 are correlated with the decrease of the Risk of Malware Infection. The value of the Pearson coefficient indicates that the decrease of the Democracy Index is correlated with the decrease of the Risk of Malware Infection.

Figure 5: Risk of Malware Infection and Democracy in the Netherlands, 2011-2016

Sources: Kaspersky Lab; Economist Intelligence Unit

Sources: Kaspersky Lab; Economist Intelligence Unit

The ICT Development Index (I. V.) and the Risk of Malware Infection (D. V.) are close to a null correlation of R= 0.02. Figure 6 shows that the Risk of Malware Infection has is oscillating, while the ICT Development Index has a relatively constant growth.

Figure 6: Risk of Malware Infection and ICTs in the Netherlands, 2011-2016

Sources: Kaspersky Lab; United Nations International Telecommunication Union

Sources: Kaspersky Lab; United Nations International Telecommunication Union

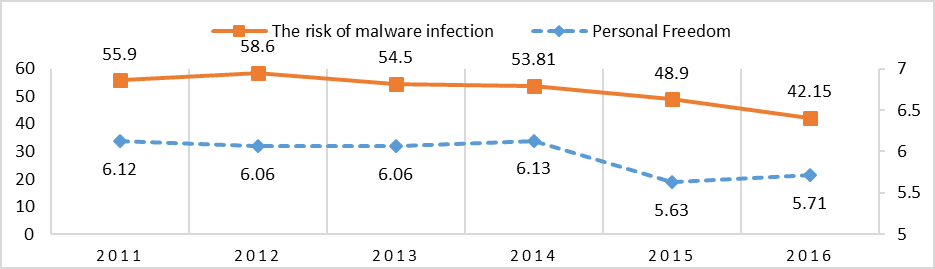

In Russia, the strongest correlation is between the Personal Freedom (I. V.) and the Risk of Malware Infection (D. V.) with R= 0.86. Figure 7 indicates that the decrease of the Personal Freedom Index is correlated with a decrease of the Risk of Malware Infection.

Figure 7: Risk of Malware Infection and Personal Freedom in Russia, 2011-2016

Sources: Kaspersky Lab; Vásquez and Porčnik, The Human Freedom Index 2018

Sources: Kaspersky Lab; Vásquez and Porčnik, The Human Freedom Index 2018

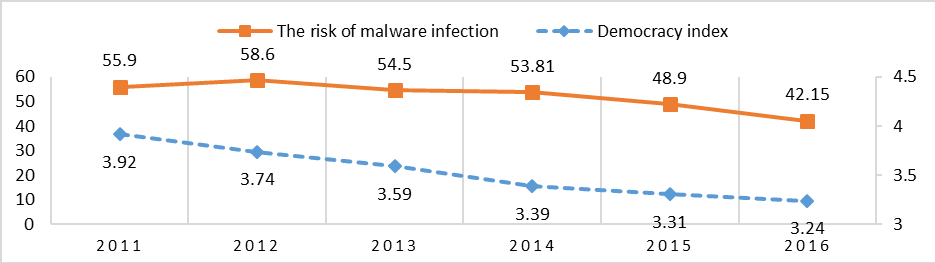

The correlation with the Democracy Index is strong and positive with R= 0.81. Figure 8 shows a continuous decrease of the Democracy Index correlated with a decrease of the Risk of Malware Infection. This indicates that the decrease of the democratic performance leads to higher cybersecurity.

Figure 8: Risk of Malware Infection and Democracy in Russia, 2011-2016

Sources: Kaspersky Lab; Economist Intelligence Unit

Sources: Kaspersky Lab; Economist Intelligence Unit

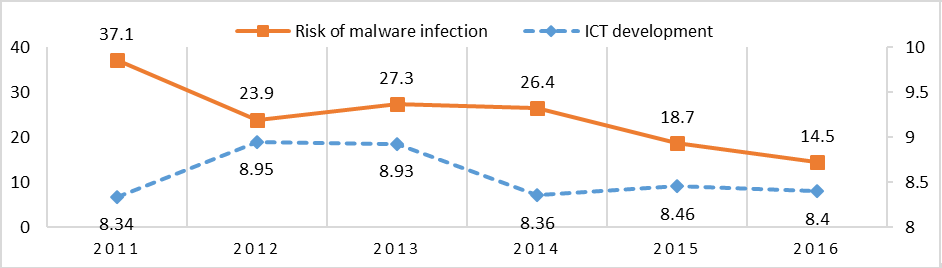

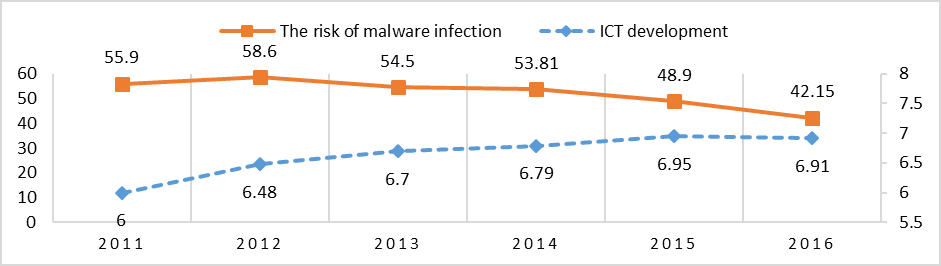

The last set of variables, ICT Development Index (I. V.) and the Risk of Malware Infection (D. V.) feature a strong and negative correlation with R= -0.64. The relation between the two variables is mixed (see Figure 9). In general, the increase of the ICT Development Index leads to the decrease of the Risk of Malware Infection, with an anomaly in 2012, where we observe that the Risk of Malware Infection increased, although the ICT Development Index increased.

Figure 9: Risk of Malware Infection and ICTs in Russia, 2011-2016

Sources: Kaspersky Lab; United Nations International Telecommunication Union

Sources: Kaspersky Lab; United Nations International Telecommunication Union

Further Considerations

Even though it is being advocated that it transcends the national borders and the state’s expertise, cyberspace bears tremendous importance for national security and is such influenced by the political culture. The design of the security strategy in the traditional operational domains (air, sea, land) is highly influenced by political culture and this research shows that this aspect is also valid for cybersecurity. The selected states are contrasting in the manner they frame the aspects of cybersecurity. Thus, culture is so powerful that managed to influence even an inherently technical aspect.

The correlation between the Personal Freedom and the Risk of Malware Infection is quite eye-opening as it indicates the impact that the political culture has on the cybersecurity. For China and the Russian Federation, the decrease of Personal Freedom leads to a decrease of the Risk of Malware Infection. This confirms the hypothesis ‘the highest the Personal Freedom is, the highest is the Risk of Malware Infection’ (A. H1). On the other hand, in the Netherlands the trend is reversed, namely ‘the highest the Personal Freedom is, the lowest is the Risk of Malware Infection’ (A. H2).

Although the cyberspace was built on self-governing basis, it quickly became necessary to adopt security and controlling measures. The states have a different view on what constitutes the cyberspace, thus they manifest a different strategy to secure it. Notably, this is often seen on the level of control imposed by states on the access and the activity on the internet through regulation and monitoring activities (Eriksson and Giacomello 2009, 209). Personal Freedom is only an element of the state control constellation in the cyberspace.

Many states, both democratic and totalitarian are already “controlling what their citizens can and cannot do on the Internet” (Cavelty 2014, 8). This study showed that for China and the Russian Federation, the control over the internet does not serve only to consolidate the state power, but it also used to increase the cybersecurity. On the other hand, in the case of the Netherlands higher freedom leads to stronger cybersecurity.

There was a strong and positive correlation of the Democracy Index for China and Russia, which confirms the hypothesis ‘the highest the democracy index is, the highest is the risk of malware infection’ (B.H1). In the case of the Netherlands there was also a positive correlation, which also confirms the hypothesis B.H1, which probably is resulted from the lack of constancy of the Democracy Index. Anyhow, the result is quite worrying as it indicates that the cybersecurity is built upon a weaker democracy. In the case of Netherlands, this result is contradictory with the previous one, aspect which shall be further analyzed.

The interesting correlation is related to the ICT Development Index, which has a strong and negative correlation for China and Russia and close to null for the Netherlands. The negative correlation for China and Russia indicates that ‘the highest the ICT Development Index is, the lowest is the risk of malware infection’ (B.H1). For the Netherlands on the other hand, there is no correlation between the two variables (B.H0). Still, it would be a major error to draw hasty conclusions in this case, reason why further research is needed.

Conclusion

The results lead to the conclusion that a factor which influences the cybersecurity is the political culture. All the states selected in the study have a different cultural background. The Netherlands features a stable Western democracy and the citizens are enjoying Western values. Russia has the Soviet Union and Slavic heritage. China is still influenced by its ancient Chinese culture, along with its present communist regime.

On top of that, each country views the cyberspace from a different perspective. Therefore, like the other security sectors, cybersecurity reflects a country’s political culture. Each country has a unique profile which matches the needs and the interests of that nation.

The article was originally published in The Visio Journal 3 (2018)

References

Aycock, J. 2006. Computer Viruses and Malware. Springer.

Cavelty, M. D. 2014. Breaking the Cyber-Security Dilemma: Aligning Security Needs and Removing Vulnerabilities. Center for Security Studies: 701–715.

China Copyright and Media. 2016. National Cyberspace Security Strategy. Consulté le November 20, 2018, sur https://chinacopyrightandmedia.wordpress.com/2016/12/27/national-cyberspace-security-strategy/

Dutch Ministry of Defence. 2012. The Defence Cyberstrategy.

Eriksson, J., and G. Giacomello. 2009. Who Constrols What, and Under What Conditions? International Studies Review, 206-210.

Federation Council (Russia). 2014. КОНЦЕПЦИЯ СТРАТЕГИИ КИБЕРБЕЗОПАСНОСТИ РОССИЙСКОЙ ФЕДЕРАЦИИ” [“The Strategic Concept of Cyber Security of Russian Federation”].

Funk, C., and M. Garnaeva. 2013. Kaspersky Security Bulletin 2013. Overall Statistics for 2013, https://securelist.com/analysis/kaspersky-security-bulletin/58265/kaspersky-security-bulletin-2013-overall-statistics-for-2013/#04.

Garnaeva, M., at al. 2014. Kaspersky Security Bulletin 2014. Overall statistics for 2014, https://securelist.com/analysis/kaspersky-security-bulletin/68010/kaspersky-security-bulletin-2014-overall-statistics-for-2014/.

———. 2015. Kaspersky Security Bulletin 2015. Overall statistics for 2015, https://securelist.com/analysis/kaspersky-security-bulletin/73038/kaspersky-security-bulletin-2015-overall-statistics-for-2015/.

———. 2016. Kaspersky Security Bulletin: Overall statistics for 2016.

Guinora, A. N. 2017. Cybersecurity. Geopolitics, law, and policy. London and New York: Routledge.

United Nations – International Telecommunication Union (ITU). 2012. Measuring the Information Society. Geneva: International Telecommunication Union.

———. 2014. Measuring the Information Society. Geneva: International Telecommunication Union.

———. 2016. Measuring the Information Society Report. Geneva: International Telecommunication Union.

———. 2017. Measuring the Information Society Report. Geneva: International Telecommunication Union.

Namestnikov, Y. 2012. Kaspersky Security Bulletin. Statistics 2011, https://securelist.com/analysis/kaspersky-security-bulletin/36344/kaspersky-security-bulletin-statistics-2011/.

Namestnikov, Y., and D. Maslennikov. 2012. Kaspersky Security Bulletin 2012. The overall statistics for 2012, https://securelist.com/analysis/kaspersky-security-bulletin/36703/kaspersky-security-bulletin-2012-the-overall-statistics-for-2012/.

National Coordinator for Security and Counterterrorism. 2013. National Cyber Security Strategy 2: From awareness to capability.

Shaohui, T. 2017. International Strategy of Cooperation on Cyberspace, http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2017-03/01/c_136094371.htm

The Economist Intelligence Unit. 2017. Democracy Index 2016. Revenge of the ‘deplorables’. London, New York and Hong Kong: The Economist.

Vásquez, I., and T. Porčnik. 2018. The Human Freedom Index 2018. A Global Measurement of Personal, Civil, and Economic Freedom. Washington, D.C: Cato Institute, Fraser Institute and Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom.

Yarger, H. 2008. “Towards A Theory of Strategy: Art Lykke and the Army War College Strategy Model.” In The U.S. Army War College Guide to National Security Issues, Volume I: Theory of War and Strategy, edited by J. R. Cerami and J. F. Holcomb, Jr., 43-49. Carlisle: Strategic Institute Studies.