The paper focuses on the concept of populism in practice in the countries of the Western Balkans, mostly in Serbia, Montenegro, and Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the use of state institutions and government-controlled media to propagate populist narratives. The basic research question relates to the nature of this populism, in the context of the theoretical framework of the given term, as well as the future challenges of the region.

In order to answer the research questions, scientific methods of description, comparison, and classification were used, along with an extensive collection of available data. Through research and a comparative analysis of the nature of populist policies in the Western Balkans, it can be seen that these policies are basically very similar – they are multi-year populist policies that trace their roots back to the 1990s and the breakup of the former Yugoslavia, and that the most important path for these countries is their integration into the European Union, which, although very slow, is still possible.

However, a more serious approach to state policies and more significant support from the European Union is needed for a bigger step forward. Paper concludes that there are also other temporary alternatives to institution building and the fight against populism, like Open Balkans initiative or upgrading the CEFTA agreement (Central European Free Trade Agreement). These would be increasing the living standards in Western Balkans countries.

Introduction

“After Nikola Pašić, I will be someone who has been in power for the longest time,” said Aleksandar Vučić on April 3, 2022, at a press conference at which he declared his victory in the presidential elections in the Republic of Serbia. This is his second consecutive term as President after he spent one term as Prime Minister of the Republic of Serbia. A little further west, in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Milorad Dodik was elected a member of the presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina from the ranks of the Serb people.

Other countries in the Western Balkans are also characterized by the strengthening of the power and political influence of populist leaders from the 1990s, whose populist rule is increasingly taking the form of autocracy. One of the main reasons for the strengthening of populist movements in Europe, especially in a democratic turmoil such as the Western Balkans, is the creation of a growing gap between democratic ideals, ie democracy in its original form, and the actual events and functioning of democracy and political processes in society.

Thus, according to a survey conducted by the Faculty of Political Science at the University of Zagreb in 2012, 49% of respondents said that democracy is the best possible form of organization of the political system, but only 3% expressed satisfaction with the way democracy works in Croatia. Poorer functioning of democracy, together with other causes such as low level of education, financial crisis, and poor infrastructure is fertile ground for strengthening populism, whose basic characteristics are according to Lutovac (2022), appealing to the will of the people, first and foremost, and then challenging or undermining the institutions of representative democracy, as well as antagonistic attitudes towards elites and “dangerous others” who threaten the state and (or) the nation.

Concept of Populism

Populism is one of the longest-running features of politics and a political concept (Roberts, 2006) – on the left and on the right – sometimes more, sometimes less, without a clear global synchronization (Brubaker, 2017). The number of populist movements has been growing since 1990, which is why populism has been identified as one of the key political phenomena of the 21st century (Longley, 2022). Charles Postel (2016) calls it a stable current – with its proposals for making a more just and equitable society and under a variety of names — antimonopolist, farmer-labor, populist, democratic socialist, nonpartisan, progressive.

From Donald Trump to Brexit, from Hugo Chávez to Podemos, the term has been used to describe leaders, parties, and movements across the globe who disrupt the status quo and speak in the name of “the people” against “the elite” (Moffitt, 2020). It is used so often that it is sometimes unclear what it represents. That is why Serhan states that the term is meaningless, explaining that words like populist and nationalist, once confined to academic circles, have become fixtures in the lexicon. Countless books and articles have been written on the subject. The pope has weighed in on the matter as well, declaring populism an “evil” that “ends badly” (Serhan, 2020).

Therefore, one acceptable definition offered by Moffitt and Tormey (2013) is that populism is a “political style” or a way in which certain politicians behave, striving to achieve performance in the short term. Populism has been present; however, it was difficult to establish a consensus around this notion. In a review of theoretical literature, Deiwiks states that in the more recent literature there is agreement on at least two characteristics that are central to populism: a strong focus by populist leaders on the “people”, and an implicit or explicit reference to an “anti-group”, often the political elite, against which the “people” is positioned.

The usefulness of such a minimal definition is shown by looking at cases of populism in Russia, the United States, Western Europe, and Latin America (Deiwiks, 2009). This is just one of the key features of the growing populism in the Western Balkans, which will be the subject of this paper. The first focus on “people” means enabling, or more precisely restoring, the power of “people”, most clearly stated through the slogan “power to the people” (Roberts, 2015). The second characteristic refers to open hatred and struggle against a certain group – which is identified by populists as the one against the “people”.

There are various causes of populism, but it mainly comes down to the fact that institutions are not able to meet the expectations of citizens. That is why Kenneth M. Roberts (2015) believes that the story of populism should focus on the story of institutions – the political representativeness of political parties, civil society, and social movements.

Urbinati (2019) puts forward an interesting thesis that populism in power is a new form of mixed government, in which one part of the population achieves a preeminent power over the other (s), and that it competes with constitutional democracy in conjoining a specific representation of the people and the sovereignty of the people. It attains this meld by instantiating what he calls a direct representation, a kind of democracy that is based on a direct relationship between the leader and the people. Thus, populism depends on the state of institutions, but also on the state of democracy in a society.

Growth of Populism in Europe

Populist movements in Europe are gaining more and more support from voters every year (Boros et al., 2020). One of the reasons for its rise is the Great World Economic Crisis of 2008, and it is especially important to point out 2016 as a year that is important for the further rise of populist and anti-establishment movements in Europe.

Namely, Brexit (The Guardian, 2016) began that year, there was a migrant crisis (USA for UNHCR, 2016), terrorist attacks (USA Today, 2016), the strengthening of right-wing political parties (Kattago, 2019), and all this contributed to the development of populism not only in Europe but also in the world. According to The Foundation for European Progressive Studies (FEPS), more than 80 active populist parties were founded between 2015 and 2019, while according to their end-2018 poll, 30.3% of European voters vote for populists, while in 2017, that number was 26% (Ibid., 2020).

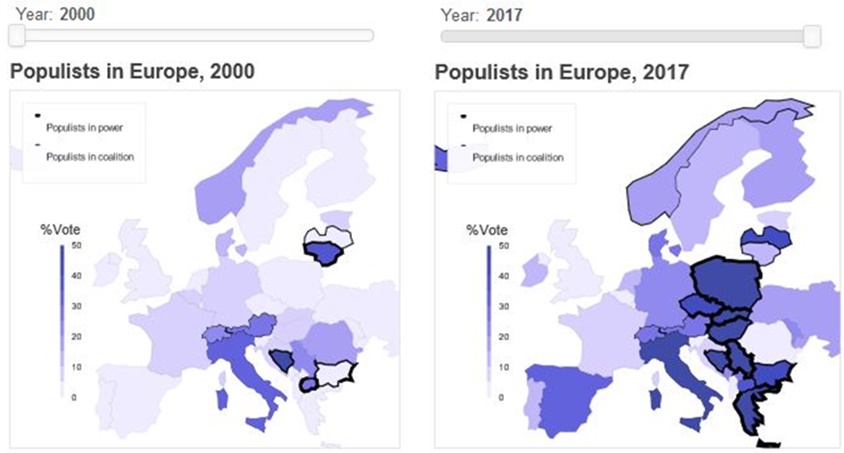

Figure 1 shows the actual strength of populist movements in Europe in 2017 compared to 2000, i.e., it is evident that populist movements in many countries have significantly strengthened compared to the period of 2000.

Figure 1. The growth of populism in Europe in the period 2000 – 2017

Source: Tony Blair Institute for Global Change (2017).

The future of populist movements also depends on how Russia’s attack on Ukraine, which began in February 2022, will affect the change of political forces in the world, ie, can this event, as some authors (NY Times, 2022) believe, bring the final victory of liberal forces over populist?

However, the situation in practice is currently significantly different. In Hungary and Serbia, a convincing victory was won by populist leaders – Viktor Orbán and Aleksandar Vučić (Starcevic, 2022), while in the elections in France, the candidate of the extreme right, Marine Le Pen, was very close to victory in the elections (France24, 2022).

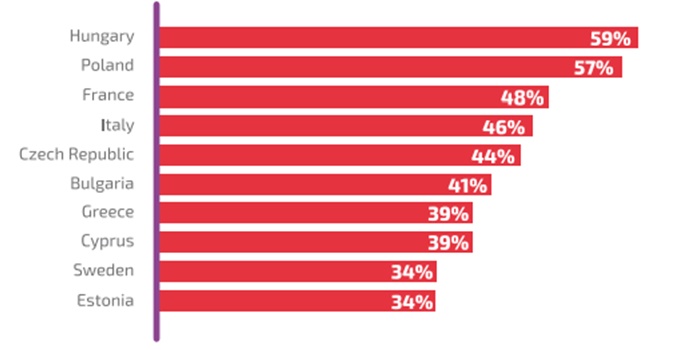

The report of the Foundation for European Progressive Studies entitled “The State of Populism in Europe in 2020” (Boros et al., 2020) shows us that Europe is increasingly leaning towards right-wing populist political parties (See Figure 2), so the results of research presented in this report show that Europe has support for left-wing populist parties is declining, while support for right-wing populist parties has increased.

The situation in which the world finds itself is currently further conducive to the development of right-wing populist parties. The consequences of the Coronavirus pandemic, global inflation, energy and economic crisis caused by the attack on Ukraine, supply disruptions around the world, the migrant crisis bring us a challenging time that populists could use to further strengthen their position.

Figure 2. Countries with the largest increase in support for populist parties in 2019

Source: Boros et al., 2020.

Populism in Western Balkans

Due to its democratic stagnation, political and economic crises, and the exodus of the population, especially the young, the Western Balkans are fertile ground for populist rhetoric. In the following, we will make a brief overview of the state of populism in Serbia, Montenegro, and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Populism in Serbia

When analyzing populism in Serbia and other countries in the Western Balkans, it is important to conclude that the weakness of democracy is one of the main reasons for the emergence of populist policies, and in order to understand the current political situation in Serbia and the inviolable rule of populist Aleksandar Vučić, the paper gives an overview of events that led to such developments.

After the disintegration of Yugoslavia, the main political character in Serbia was Slobodan Milošević. His rule was marked by the strengthening of nationalist rhetoric in which the idea of a Greater Serbia was propagated (MacDonald, 2018). Milošević profiled himself as the unofficial leader of all Serbs,[1] and in that, he had the support of the public, which was strongly influenced by state propaganda and the media he controlled (Fogg, 2006).

In a report entitled “Political Propaganda: All Serbs in a State: The Consequences of the Instrumentalization of the Media for Ultra-Nationalist Purposes”, Professor Renaud de la Brosse (2003) cites several reasons why the population of Serbia at the time was easy prey for nationalists:

- Disoriented population in the context of the general crisis (abandonment of the system of values and ideology of communism, difficult economic, political, and social situation, a lost population whose ideals have disappeared),

- Support for the regime by the main creators of public opinion (such as “Politika”, “Radio-Television of Serbia”, the Orthodox Church),

- State media is the main source of information for 90% of the population (lack of independent media)

- Impossibility of democratic change of government (under the monopoly of state power in all spheres of social, political, and media life, the opposition had no chance to win the election)

- Absence of critical spirit.

The non-existence of any alternative to the reality created by the government and the control of the media kept Slobodan Milošević and his ideology in power. As one of the soldiers of that ideology, at the end of the 1990s, Aleksandar Vučić appeared. He became the Minister of Information of Serbia in the government formed by Milošević’s Socialist Party of Yugoslavia with the Serbian Radical Party of which he was a member.

The results were the Public Information Law (Committee to Protect Journalists, 2000), which resulted in heavy fines for the media and the closure of several media outlets. As a prominent member of the Serbian Radical Party, Aleksandar Vučić has already been established as a nationalist and his statement “For every Serb killed, we will kill 100 Muslims”[2] is well known.

One of the key moments in recent Serbian history is October 5, 2000, when the regime of Slobodan Milošević fell and new – pro-European political parties led by Zoran Đinđić, which advocated Serbia’s European integration, came to power. However, the assassination of Zoran Đinđić, the Serbian Prime Minister at the time, led to disappointment among voters in Serbia and the loss of hope that democratic changes could be made in Serbia.

According to Kovačević (2020), this evident delay of Serbia in the process of democratization is caused by various factors that are fertile ground for populists and their ideas, which in recent years, especially with the coming to power and strengthening of Aleksandar Vučić’s policy, has become an integral part of political discourse in Serbia. The author uses Tagart’s (2004) model which explains the emergence of populism through clearly defined characteristics that need to be checked, emphasizing that populist movements, parties and individuals are characterized by the following characteristics:

- Hostility towards representative democracy.

- The concept of serving the “fatherland” and the “people”.

- Lack of basic values and principles and chameleon character.

- Spreading the atmosphere of extreme crisis.

- The important role of the charismatic leader.

According to Šalaj (2012), the central idea of populism is that society is divided into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups: honest people and a corrupt elite. Populists emphasize the idea of good and honest people who have been deceived and manipulated by corrupt, incompetent, and interconnected elites.

The role of the media in spreading populist ideas is important, especially in digital media in recent times. The lack of responsibility of the media for the presented content and their control by the authorities are an ideal combination for spreading populist ideas. Populists hide behind the majority, behind the people. They propagate the idea that they are on the side of the people in the fight against some others, enemies, and groups working against the people.

Table 1. Frequency of populism in the narratives of presidential candidates in Serbia (2017)

| Candidate | Percentage |

| Janković | 0.9% |

| Jeremić | 37,1% |

| Parović | 37.0% |

| Radulović | 30.0% |

| Vučić | 82,1% |

| Obradović | 46,9% |

| Šešelj | 46,6% |

| Popović | 44,1% |

| Stamatović | 45,5% |

| Čanak | 35.0% |

Source: Bešić, 2017.

In Table 1 we can see that all presidential candidates in the 2017 Serbian elections, except Janković, had a significant percentage of populism in their narratives, and convincingly the winning candidate – Aleksandar Vučić had the most.

A characteristic of populism according to Tagart is the spread of the atmosphere of extreme crisis. The media wholeheartedly help in that, and, as Perić and Kajtaz (2013) note, politics and the media are increasingly connected because politics establishes control over the media, primarily by providing them with financial support in various ways.

Thus, the research from 2018 established that two Serbian tabloids (Srpski Telegraf and Informer) had the words “war” and “conflict” on the front page as many as 265 times in the period from April 1, 2016, to March 31, 2017 (Janjić and Šovanec, 2018). In this way, the media creates the illusion of a great threat, danger to the people, constant plans of enemies of the state to attack the state, and the people, and then through the same media presents populist ideas about a president who does not allow anyone to attack the people.

Table 2 shows only some of the headlines of Serbian tabloids in the past years, but several conclusions can be drawn from this. First of all, Aleksandar Vučić pays a lot of attention to media control (Istinomer, 2018). By controlling the media, he also controls public opinion. Also, from the headlines of the tabloids in Table 1, we see the classic action of a populist – he simultaneously creates an atmosphere of imminent danger, and at the same time presents himself as the only savior, as a fighter for the people, for the truth.

Table 2. Covers Serbian tabloids[3]

| TITLE | TABLOID / NEWSPAPER | YEAR PUBLISHED |

| Only in informer! ISIL attacks Dečani | informer.rs | 2016 |

| Wahhabis reached the suburbs of Belgrade | novosti.rs | 2016 |

| The Hague rapes the Serbs again! Radovan Karadžić was sentenced to 40 years in prison on the 17th anniversary of NATO aggression! | informer.rs | 2016 |

| The Albanians are preparing a new “Storm” and a general attack on the Serbs: Vučić gave them a deadline to think three times until September 30! | objektiv.rs | 2022 |

| Americans are preparing to bomb Serbia again! Watch out now, as there will be a new war in B&H, and Serbia will stand with Republic Srpska | informer.rs | 2021 |

| If Vučić is there, the truth about Jasenovac will be known: The Ustaše wanted to change history, so they attack our president! | objektiv.rs | 2022 |

| Who and why attacks Aleksandar Vučić now that he has the highest support of the people? | telegraf.rs | 2017 |

Source: Authors.

One of the characteristics of populist movements is the important role of the charismatic leader. Starting from Nikola Pašić through Josip Broz Tito, Slobodan Milošević, Vojislav Koštunica to Aleksandar Vučić, the cult of personality has always been nurtured on the territory of the Republic of Serbia, regardless of the territorial and political organization of the state.

Thus, it is important for Serbia to mention, as Kovačević (2020) notes, that power often goes to individuals, and does not remain in accordance with constitutional powers, which shows the lack of institutionalized government. This is identified in the best way in the example of Slobodan Milošević, Aleksandar Vučić and, in part, Boris Tadić, who, regardless of their position, were central figures in political life in Serbia.

According to the analysis from 2017 (Jahić, 2017), in the period from 01.01.2016 – 31.12.2016, Aleksandar Vučić’s photograph appeared on the front page of the newspaper as many as 681 times, while his name was mentioned more than 150 times. At the same time, the opposition has almost no space in the daily press, except when it is written negatively about them. All this supports the claim that the media are an extremely powerful tool in the hands of the authorities in Serbia.

Also, Lutovac (2022) cites an example of a text written by Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić in the daily “Politika” entitled “Elite and Plebs” (Vučić, 2017), which is full of examples of populist communication. In the text, Vučić addresses the people, and the people are only those citizens of Serbia who support him. He attacks the elite, calling it a qualifying elite, which means those who criticize him.

As Lutovac (2022) points out, Vučić is rhetorically fighting for the poor and disenfranchised at the same time, and in practice, he is the one who generates poverty and disenfranchisement. He publicly promotes the idea of adhering to the European Union, and in practice, he shows his orientation towards the East and Russia.

Another characteristic of populism according to Tagart is its chameleon character. Thus, as Lutovac (2022) notes, the populist discourse in Serbia can, according to the needs of the leader, incorporate advocacy for the free market and competition at a given moment, and affirm the idea of equality and fair redistribution of economic goods in the next. Often in public, Vučić communicates in a conciliatory tone, with a lot of understanding towards everyone, even those he considers enemies, but at the same time, his closest associates go public with views that Vučić himself supports and initiates but does not want to declare about them in person.

Finally, populism in Serbia is closely linked to nationalism, nativism, and xenophobia (Ibid., 2022). In this case, the people are equated with the state, and every enemy of the people is also the enemy of the state. We can conclude that today the citizens of Serbia are hostages of the populist policy of Aleksandar Vučić. Today, the entire political, social, and media order in Serbia is in the function of keeping Aleksandar Vučić and his associates in power. By controlling the media, they create public opinion in Serbia and adapt it to their needs. It is not wrong to conclude that there is less democracy in Serbia today than in the time of Slobodan Milošević.

Populism in Montenegro

Montenegro gained independence in 2006. Until then, this country was in the state union with Serbia called Serbia, and Montenegro. First, Montenegro was ruled by the Democratic Party of Socialists of Montenegro or DPS, as the successor to the former Communist Party, whose most prominent representatives Momir Bulatović, Svetozar Marović, and Milo Đukanović were very close to Slobodan Milošević’s policy at the time.

That’s why Montenegro did not have ambitions for independence in that period, unlike other republics of the former Yugoslavia. However, after October 5th and the fall of Milošević, the DPS has positioned itself as the leader of Montenegro’s independence movement. All of this resulted in Montenegro’s independence in 2006.

Džankić and Keil (2017) analyze populism in Montenegro on the example of its most important party – the Democratic Party of Socialists (DPS), using the aforementioned Taggart framework. They state that, although the DPS per se is not a populist party, in the 25 years of their rule we find numerous elements of populism.

First of all, “othering” political opponents, the emphasis on the heartland, the back of the party’s ideological profile, the reproduction of the crisis, charismatic leadership, and chameleonic nature can be recognized in the DPS. These traits are often intertwined. Thus, during the 1990s, during the wars in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Croatia, the DPS was very close to Slobodan Milošević’s policy, supporting the activities of the Yugoslav People’s Army (Jugoslovenska narodna armija – JNA), and imaginary opponents were all those who were against these ideas. Due to that, the position of national minorities in Montenegro is significantly more difficult.

However, as Milošević’s power weakens, so does the ideology of the DPS. According to the authors (Džankic and Keil, 2017), from the 1997–2000 year, the perception was created among the supporters of the DPS and Milo Đukanović that the enemies are those who support Milošević. This is where the chameleon nature of the DPS rule manifests itself, as one of the most significant features of populism according to Tagarrt. Over time, this turned into an initiative for the independence of Montenegro, so the “enemies” became those who opposed it.

The authors state that the connection between the people and Montenegro as a homeland was at the center of the DPS’s political rhetoric. However, that also changed like a chameleon with political changes, first in Serbia, and then in Montenegro. First, in the 1990s, during its closeness to Slobodan Milošević’s policies, the DPS in Serbia supported the JNA’s (Yugoslav People`s Army) war activities, especially in Croatia, proudly pointing out that Montenegrin soldiers were engaged in what they called “war for peace”. However, with the fall of Milošević, and the strengthening of the idea of Montenegrin independence, the DPS changed its political orientation, emphasizing that Montenegro was a “hostage of Serbian politics”.

During that period, the DPS actively worked on the promotion of national affiliation, strengthening the bond between the people and the state and the “heartland” through language, state symbols, and the country’s path to the European Union. As in Serbia, so is the cult of personality in Montenegro. Thus, Milo Đukanović, like Milošević and Vučić in Serbia, has been the central political figure in Serbia for years and power and authority are always tied to the function he performs.

Populism in Bosnia and Herzegovina

Like many other things, populism in Bosnia and Herzegovina is very specific. Populism is closely connected with national affiliation, with constituent peoples and that is why Fejzić (2021) calls it ethnonational populism and states that it appears

“an implication of political reaction of party elites to important issues of a practical policy such as constitutional and political reforms, arrangements with international financial institutions, economic crisis, the disintegration of state integration into NATO, etc.”

It can be said that populism in B&H has several identities: national, religious, territorial and all that, as the author states, makes the state government in Bosnia and Herzegovina inefficient.

“Republika Srpska has embarked on a path of exit from Bosnia and Herzegovina from which there is no return” (ATV BL, 2020) Milorad Dodik said in February 2020, noting that “Republika Srpska has two choices – one of which is to allow itself to quietly disappear and collapse through a deadly package made by the international community and the Bosniak side in Sarajevo.”

We will observe populism in Bosnia and Herzegovina on the example of Milorad Dodik, currently a member of the Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina from the ranks of the Serbian people. He is the political party Alliance of Independent Social Democrats (SNSD) president. After serving as Prime Minister and President of the Republika Srpska entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina, he currently serves as a member of the Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina from the ranks of the Serb people.

It is characteristic of him, as well as of Aleksandar Vučić, that regardless of their position, he is the central political figure in the entity of Republika Srpska. His policy is characterized by secessionist threats, strong nationalism, and denial of anything to do with Bosnia and Herzegovina, even though he is a member of the presidency. He is another of a plethora of politicians who began their political careers in the 1990s as members of the Republika Srpska National Assembly, an entity whose entire wartime leadership has been convicted by the International Court of Justice of the most serious war crimes, including genocide[4].

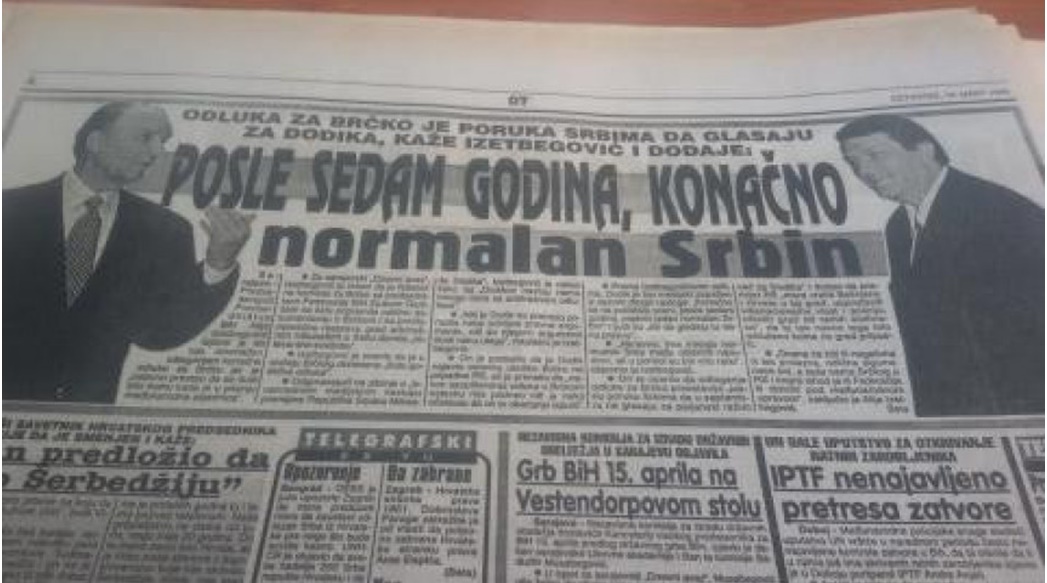

However, at the end of the 1990s, Dodik, as a true populist, recognized the change in the political situation, and softened his political views, which is why even the then President of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Alija Izetbegović, as well as the international community consider him a good political interlocutor (RTV BN, 2022; Associated Press, 2022).

Figure 3. Alija Izetbegović (for Milorad Dodik op.a.): “After seven years, finally a normal Serb”[5]

Source: RTV BN, 2017.

That is how Milorad Dodik began his political rise in Bosnia and Herzegovina. His policies in the coming years will be marked by a series of contradictions, which corresponds to the chameleon-like character of his populism (Associated Press, 2022).

As a sovereign ruler at all levels of government in the Republika Srpska entity, Milorad Dodik, by controlling the media, also controls public opinion, maintaining a state of constant crisis and danger, constant danger lurking for Republika Srpska, constant plans for some kind of attack. In that, he received wholehearted political and media support from neighboring Serbia, so the media are full of headlines like:

- NEW ATTACK ON THE REPUBLIKA SRPSKA We do not rule out the possibility of reacting (ALO!, 2021)

- GENERAL ATTACK ON THE REPUBLIKA SRPSKA AND THE RIGHTS OF THE SERBIAN PEOPLE (Glas Srpske, 2022)

- ATTACK ON THE TRUTH AND THE REPUBLIKA SRPSKA: Strong reactions to the ban on university professor Miloš Ković from entering BiH (Novosti, 2022)

- WAR SCENARIO FOR ATTACK ON REPUBLIC OF SRPSKA LEAKED: This is how the BiH Army plans to conquer it (Telegraf, 2016)

- DANGEROUS! USTAŠE AND NATO ARE PREPARING OPERATION ‘PRIJEDOR’! Croats are hitting Republika Srpska with “Kiowa” and “Hellfire” rockets! (Informer, 2016)

- THERE IS AN INTENTION TO DESTROY REPUBLIKA SRPSKA THROUGH WAR (Vesti, 2016)

In this way, the population is intimidated, the illusion of endangerment is created and an atmosphere in which only a populist leader – in this case, Milorad Dodik – can protect the population. However, the loss of support and the consequent loss of power is what scares populists like Milorad Dodik the most. In order to strengthen his position before the upcoming elections, Milorad Dodik started at least declaratively the action of withdrawing the Republika Srpska from the institutions of Bosnia and Herzegovina (WDR, 2021).

This was formalized in December 2021, when the Assembly of the Republika Srpska adopted conclusions (Al Jazeera Balkans, 2021) on the transfer of competencies from the institutions of Bosnia and Herzegovina to the institutions of the Republika Srpska. With the mentioned Conclusions, it is planned to establish the Army of the Republika Srpska, the Agency for Medicines of the Republika Srpska, to withdraw from the Indirect Taxation Authority of Bosnia and Herzegovina. This was condemned by both the international community and the opposition in the Republika Srpska, which is aware that such actions introduce the entity to a very unstable period.

Although he subsequently held public appearances in which he stressed that the process of transferring competencies from the state of Bosnia and Herzegovina to the Republika Srpska entity was underway, Milorad Dodik still showed that it was a populist move and postponed the implementation of the Republika Srpska Army Law (RTV BN, 2022).

Another populist element we identify in Milorad Dodik’s policy is the issue of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s membership in NATO. Although he does not miss the opportunity to say in public that Republika Srpska and he will never agree to Bosnia and Herzegovina’s membership in NATO[6], his party member Nebojša Radmanović, as a member of the Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina, signed the document Action Plan for BiH’s NATO membership and later stated that this was then the position of the National Assembly of the Republika Srpska[7].

From all the above, we can conclude the nature of Dodik’s populist policy. Its essence is that Milorad Dodik is telling the media what his voters want to hear, but that he is essentially doing the exact opposite. His plans and threats have so far remained declarative, with no concrete actions to implement, but as his political career draws to a close, it remains to be seen how far populist Dodik can go to stay in power and what his end game will be.

Present and Future Challenges

The Western Balkans region has problems with populism. The feature of these populisms is their combination with clientelism and corruption (Sotiropoulos, 2017). Based on the above, the populists in power in the Western Balkans can remain in power, creating a strong resource base that serves them to manage the entire society. In particular, the regime of Aleksandar Vučić in Serbia, Nikola Gruevski in Macedonia, and the politics of Milorad Dodik in Republika Srpska, or Albin Kurti in Kosovo have attracted international attention with scholars classifying their form of leadership culture from illiberal democracy to authoritarianism (Sotiropouloss, 2015).

There are several key challenges in the context of growing populism in the Western Balkans:

- Process of EU integration of the Western Balkans.

- Russian and Chinese special interests.

- The Open Balkans and the economic future.

When it comes to EU integration, the Western Balkans region currently represents a “hole” within the common EU market. Currently, five states are in the status of candidate countries – Albania, the Republic of Northern Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Turkey, while Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Kosovo are potential candidates. This creates difficulties in the process of building much-needed institutions that would oppose growing populism, but also safeguarding human rights, which were particularly violated during the COVID-19 pandemic (Jahić, Hasić, and Čavalić, 2021).

Currently, the EU integration of the region represents the biggest challenge, but also a chance to fight populism. The good news is that in July 2022, the European Union’s 27 members have agreed to open accession negotiations with Albania and North Macedonia. EU accession negotiations with Nort Macedonia and Albania have been pending sing 2020 because Bulgaria had blocked any progress for European Union accession talks with Nort Macedonia over linguistic and historical issues which also stalled Albania’s status, as the European Union treats it as part of a package (DW, 2022).

What is further worrying is the growing Russian and Chinese interest (Al Jazeera, 2021). Often, populist regimes, such as those mentioned above, seek to establish cooperation with Russian and Chinese companies, or banks, with the aim of realizing larger infrastructure projects or simply securing sources of funding. Russian interests are especially related to populism, there are even media agencies like Sputnik that openly spread Russian propaganda, which skews public opinion in the region (DW, 2021).

Ultimately, the rate of economic prosperity will determine the future of populism in the region. Currently, the Western Balkans region is growing slowly, creating fewer job opportunities, and leading to the departure of the workforce. According to Porčnik (2019), openness and regional economic integration in the Western Balkans must stimulate economic activity, investment, trade, create jobs, and increase participation in global value chains, which will increase productivity, improve economic growth, and reduce poverty.

One of the possibilities for better use of the region’s economic potential is the “Open Balkans” initiative formerly knowns as Mini Schengen- better integration of the region with the aim of the easier flow of people, goods, and capital. The problem is that this initiative is mostly propagated by populists, such as Mr. Vučić. It is therefore uncertain whether it can be institutionalized and deliver results in the long run.

Conclusion

Populism is a great challenge for all the countries of the Western Balkans. It does not help that populist movements are growing across Europe and the world. What is clear is that the populists benefit the most from current happening and the citizens of the countries where the populist’s rule have the least benefit. The paper presented the actions of some of the populist leaders. Some of these leaders have been active for more than 10 years, which shows the continuity of populism. So far, the only certainty that can help reduce populism relates to building strong institutions.

However, the question is whether it is possible to do that, understanding that there is a lack of EU support, i.e., EU integration is on a long stick. Populists are taking advantage of the current situation and continue to strengthen while preventing the development of sound institutions – all this leads to a vicious circle of populism in the Western Balkans. The only long-term solution is to speed up the EU integration process and ultimately integrate these countries into the EU.

In the meantime, it is also possible to work on trying to build regional institutions through the Open Balkans initiative or upgrading the CEFTA agreement (Central European Free Trade Agreement). The goal is to reduce the influence of populism in Balkan politics and to emphasize those policies that contribute to concrete changes – primarily through increasing the living standards of the citizens of this region.

References

[1] More about his influence on Serbs during the nineties is available in the United Nations International Criminal for the former Yugoslavia indictment for crimes committed in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, and Kosovo at the following link: https://www.icty.org/en/case/slobodan_milosevic

[2] Statement of Aleksandar Vučić: “For every killed Serb we will kill 100 Muslims”. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rDmwnfx3Ab4

[3] Some of the titles are: “An incurable disease is coming to Serbia”; “I am leaving if the people want it” (Vučić op.a.), “Everyone against Vučić”, “Our children are lurking as many as 60 sects”, “WAR” “The West overthrew Vučić”, “Vučić is giving up his mandate because of foreigners”, “Serbia is recorded and monitored by as many as 3,000 drones, etc.

[4] A list of all those convicted by the United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) along with all trial details, including verdicts, is available at: https://www.icty.org/en/cases/judgement-list.

[5] Apart from Alija Izetbegović, the then president of Bosnia and Herzegovina, who had a positive opinion of Milorad Dodik, he was also praised by other world officials during that period, so the then U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright said after the meeting with Dodik that “it felt like a breath of fresh air had blown through the room. More about the change in Milorad Dodik’s political views over the years is available at: “How Bosnia’s Dodik went from a moderate reformist to genocide-denying secessionist”, www.npr.org/2022/01/08/1071537135/how-bosnias-dodik-went -from-a-moderate-reformist-to-genocide-denying-secessionist

[6] An example from 2017: “Bosnian Serb leader Milorad Dodik said he will seek to block efforts for the country to one day become a member of NATO, insisting on military neutrality, in line with Serbia.” Available at: https://balkaninsight.com/2017/12/15/bosnia-serbs-oppose-nato-acession-bid-12-15-2017

[7] High Representative for Bosnia and Herzegovina Valentin Inzko stated in 2017 that “regarding the Membership Action Plan, the BiH Presidency has already decided on this issue in 2009. The then Presidency members, including the Serb Presidency member Nebojša Radmanovic from President Dodik’s own party, made this decision. In fact, it was Mr. Radmanović who signed BiH’s formal BiH application letter addressed to the NATO Secretary General in 2009, asking for BiH to be granted the NATO Membership Action Plan.” Available at: http://www.ohr.int/radiosarajevo-ba-interview-with-hr-valentin-inzko/

Al Jazeera Balkans. (2021, 10 December). The RS Assembly voted on the transfer of competencies from BiH to the entity. https://balkans.aljazeera.net/news/balkan/2021/12/10/danas-sporna-sjednica-entitetskog-parlamenta-rs-a

Al Jazeera. (2021, 11 October). As EU hopes fade, Russia, China fill voids across Western Balkans. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/10/11/with-no-eu-strategy-russia-china-fill-void-in-western-balkans

ALO! (2021, 23 December). NOVI NAPAD NA REPUBLIKU SRPSKU. Ne isključujemo mogućnost da reagujemo (Eng. New attack on the Republika Srpska: We do not rule out the possibility of reacting). https://www.alo.rs/svet/planeta/578705/republika-srpska-evropska-unija-napad/vest

Associated Press. (2022, 8 January). How Bosnia`s Dodik went from a moderate reformist to genocide-denying secessionist. https://www.npr.org/2022/01/08/1071537135/how-bosnias-dodik-went-from-a-moderate-reformist-to-genocide-denying-secessionist

ATV BL. (2020, 13 February). Republika Srpska je krenula na put izlaska iz BiH, s kojeg nema povratka (Eng. Republika Srpska has set out on a path out of BiH from which there is no return). https://www.atvbl.rs/vijesti/republika-srpska/republika-srpska-je-krenula-na-put-izlaska-iz-bih-s-kojeg-nema-povratka-13a

Bešić, M. (2017). Populizam u narativima predsedničkih kandidata na predsedničkim izborima u Srbiji 2017. godine. Belgrade: Institut društvenih nauka, Centar za politološka istraživanja i javno mnjenje.

Boros, T., Freitas, M., Gyori G., and G. Laki. (2020). State of populism in Europe in 2020. Brussels and Budapest: Foundation for European Progressive Studies, Policy Solutions. https://progressivepost.eu/wp-content/uploads/State-of-Populism-in-Europe-2020.pdf.

Brubaker, R. (2017). Why populism? Theory and Society 46: 357–385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-017-9301-7

Committee to Protect Journalists. (2000). Serbian Public Information Law: Full Text. https://cpj.org/reports/2000/08/serb-info-law/

De la Brosse, R. (2003). Political propaganda and the project “All Serbs in one state”: consequences of instrumentalization of the media for ultra nationalist purposes. The Prosecutor’s Office of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia. https://www.icty.org/x/cases/slobodan_milosevic/prosexp/bcs/rep-srb-b.htm

Deiwiks, C. (2009). Populism, Living Reviews in Democracy 1: 1–9.

- DW. (2021, 29 September). Western Balkans: Russia’s Sputnik skews public opinion. https://www.dw.com/en/western-balkans-russias-sputnik-skews-public-opinion/a-59357427

———-. (2022, 18 July). EU to open accession talks with Albania, North Macedonia. https://www.dw.com/en/eu-to-open-accession-talks-with-albania-north-macedonia/a-62516677

Džankić, J., and S. Keil. (2017). State-sponsored Populism and the Rise of Populist Governance: The Case of Montenegro, Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies 19(4): 1–16.

Fejzić, E. (2021). Populizam i nacionalizam u postdejtonskoj Bosni i Hercegovini: desnica, ljevica i zloupotrebe volje naroda. In V. Veselinović (ed.), Populistički duhovi vremena i izazovi demokraciji: studije o populizmima (250–267). Zagreb: Despot infinitus d. o. o.

Fogg, K. (2006). The Milošević Regime and the Manipulation of the Serbian Media. European Studies Conference, March 25, 2006. https://www.wm.edu/as//globalstudies/european/conference/pre-2009-conference-docs/fogg.pdf

France24. (2022, 25 April). “Victory” in defeat? Le Pen raises the far right’s glass ceiling, fails to crack it. https://www.france24.com/en/france/20220425-victory-in-defeat-le-pen-raises-far-right-s-glass-ceiling-fails-to-crack-it

Glas Srpske. (2022, 30 May). Општи напад на Републику Српску и права српског народа (Eng. The general attack on the Republika Srpska and the rights of the Serbian people). https://www.glassrpske.com/cir/novosti/vijesti_dana/opsti-napad-na-republiku-srpsku-i-prava-srpskog-naroda/413749

Informer. (2021, December 12). AMERI OPET MERAČE BOMBARDOVANJE SRBIJE! PAZI SAD, KAO BIĆE NOVI RAT U BIH, A SRBIJA ĆE STATI UZ SRPSKU (Eng. Americans are preparing to bomb Serbia again! Watch out now, as there will be a new war in B&H, and Serbia will stand with Republika Srpska). https://informer.rs/planeta/balkan/659418/srbija-opasnosti-ameri-slute-novi-rat-bih-novo-bombardovanje-beograda

———-. (2016, 25 March). SAMO U INFORMERU: HAG opet siluje SRBE! Radovanu 40 godina na 17. godišnjicu NATO agresije! (Eng. The Hague rapes the Serbs again! Radovan Karadžić was sentenced to 40 years in prison on the 17th anniversary of NATO aggression!). https://informer.rs/srbija/vesti/260552/samo-informeru-hag-opet-siluje-srbe-radovanu-godina-godisnjicu-nato-agresije

———-. (2016, 02 February). SAMO U INFORMERU! ISIS napada Dečane – Ekstremisti spremaju veliko zlo! (Eng. Only in informer! ISIL attacks Dečani). https://informer.rs/srbija/vesti/251247/samo-informeru-isis-napada-decane-ekstremisti-spremaju-veliko-zlo

———-. (2016, 2 September). OPASNO! USTAŠE I NATO SPREMAJU OPERACIJU ‘PRIJEDOR’! Hrvati udaraju na Republiku Srpsku ‘kajovama’ i ‘helfajer’ raketama! (Eng. Dangerous! Ustaše and NATO are preparing operation “Prijedor”! Croats are hitting Republika Srpska with “Kiowa” and “Hellfire” rockets!). https://informer.rs/vesti/politika/287215/opasno-ustase-nato-spremaju-operaciju-prijedor-hrvati-udaraju-republiku-srpsku-kajovama-helfajer-raketama

Istinomer. (2018). Decenija SNS: Godine strogo kontrolisanih medija. https://www.istinomer.rs/analize/decenija-sns-godine-strogo-kontrolisanih-medija/

Jahić, A., Hasić, M., and A. Čavalić. (2021). Human Rights during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Bosnia and Herzegovina, The Visio Journal 6: 21–33. http://visio-institut.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Visio-Journal-6-Aldina-Jahic-Merisa-Hasic-and-Admir-Cavalic.pdf

Jahić, D. (2017, 26 January). Naslovnice dnevnih novina u Srbiji: Horor, strah, užas, kraj … MediaCentar Online. https://www.media.ba/bs/mediametar/naslovnice-dnevnih-novina-u-srbiji-horor-strah-uzas-kraj

Janjić, S., and S. Šovanec. (2018). Najava rata na naslovnim stranama tabloida. Communication and Media XIII(43): 49–68. https://scindeks-clanci.ceon.rs/data/pdf/2466-541X/2018/2466-541X1843049J.pdf

Kattago, A. (2019). The Rise of Right-Wing Populism in Contemporary Europe. Tallin University.

Kovačević, D. (2020). Populizam u Srbiji nakon 5. Oktobra. In S. Orlović and D. Kovačević (eds.), Dvadeset godina 5. Oktobra (113–130). Belgrade: Faculty of Political Science University of Belgrade, Centar za demokratuju, Hanns Seidel Stiftung.

Longley, R. (2022). What Is Populism? Definition and Examples. ThoughtCo. https://www.thoughtco.com/populism-definition-and-examples-4121051

Lutovac, Z. (2022). Populizam u Srbiji. In V. Veselinović (ed.), Populistički duhovi vremena i izazovi demokraciji: studije o populizmima (209–229). Zagreb: Despot infinitus d.o.o.

MacDonald, B. D. (2018). “Greater Serbia” and “Greater Croatia”: the Moslem question in Bosnia-Hercegovina. DOI: 10.7765/9781526137258.00013

Moffitt, B. (2020). Populism. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Moffitt, B., Tormey, S. (2013). Rethinking Populism: Politics, Mediatisation and Political Style, Political studies 62(2): 381–397. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1467-9248.12032

Novosti.rs. (2022, 14 March). ATAK NA ISTINU I REPUBLIKU SRPSKU: Oštre reakcije na zabranu ulaska u BiH profesoru univerziteta Milošu Koviću (Eng. Attack on the truth and the R epublika Srpska: Strong reactions to the ban on university professor Miloš Ković from entering BiH). https://www.novosti.rs/planeta/region/1095979/atak-istinu-republiku-srpsku-ostre-reakcije-zabranu-ulaska-bih-profesoru-univerziteta-milosu-kovicu

———-. (2016, 26 January). Vehabije stigle do predgrađa Beograda (Eng. Wahhabis reached the suburbs of Belgrade). https://www.novosti.rs/vesti/naslovna/drustvo/aktuelno.290.html:587951-Vehabije-stigle-do-predgradja-Beograda

NY Times. (2022, 16. March). Will the Ukraine war end the age of Populism? https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/16/opinion/ukraine-russia-populism.html

Objektiv.rs. (2022, 25 July). Dok je Vučića, znaće se ISTINA o Jasenovcu: Ustaše bi da menjaju istoriju, pa napadaju našeg predsednika (Eng. As long as Vučić is there, the truth about Jasenovac will be known: The Ustaše wanted to change history, so they attack our president!). https://objektiv.rs/vest/1203046/dok-je-vucica-znace-se-istina-o-jasenovcu-ustase-bi-da-menjaju-istoriju-pa-napadaju-naseg-predsednika/

———-. (2022, 29 June). Albanci spremaju novu OLUJU i opšti NAPAD na Srbe: Vučić im dao rok da TRI puta razmisle do 30. septembra (Eng. The Albanians are preparing a new “Storm” and a general attack on the Serbs: Vučić gave them a deadline to think three times until september 30!). https://objektiv.rs/vest/1174186/albanci-spremaju-novu-oluju-i-opsti-napad-na-srbe-vucic-im-dao-rok-da-tri-puta-razmisle-do-30-septembra/

Perić, N., and Kajtez, I. (2013). Ideologija i propaganda kao masmedijska sredstva geopolitike i njihov uticaj na Srbiju, Nacionalni interes IX(17): 173–189.

Porčnik, T. (2019). Mini Schengen – Western Balkans`s Embrace of the Market. The Institute for Research in Economic and Fiscal Issues. https://en.irefeurope.org/Publications/Online-Articles/article/Mini-Schengen-Western-Balkans-Embrace-of-the-Market/

Postel, C. (2016). If Trump and Sanders Are Both Populists, What Does Populist Mean?. The American Historian. https://www.oah.org/tah/issues/2016/february/if-trump-and-sanders-are-both-populists-what-does-populist-mean/

Roberts, K. M. (2015). Populism, political mobilization, and crises of political representation. In C. de la Torre (ed.), The promise and perils of populism: Global perspectives (140–158). Lexington, Kentuky: The University Press of Kentucky.

———-. (2006). Populism, Political Conflict, and Grass-Roots Organization in Latin America. Comparative Politics 38(2): 127–148.

RTV BN. (2022, 18 April). Dodik ipak popušta: Odgađa usvajanje zakona o vojsci i porezima Republike Srpske (Eng. Dodik relented: Postpones adoption of law on army and taxes of Republika Srpska). https://www.rtvbn.com/4024301/dodik-ipak-popusta-odgadja-usvajanje-zakona-o-vojsci-i-porezima-republike-srpske

———-. (2017, 17 March). Kako je Alija hvalio Dodika (Eng. How Alija praised Dodik). https://www.rtvbn.com/3857026/kako-je-alija-hvalio-dodika

Šalaj, B. (2012). Što je populizam? Politološki pojmovnik: populizam. Političke analize: tromjesečnik za hrvatsku i međunarodnu politiku 3(11): 55–61. https://hrcak.srce.hr/file/209523

Serhan, Y. (2020, 14 March). Populism Is Meaningless. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2020/03/what-is-populism/607600/

Sotiropoulos, D. A. (2017). How the quality of democracy deteriorates: Populism and the backsliding of democ-racy in three West Balkan countries. LIEPP Working Paper n° 67. https://hal-sciencespo.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03458615

———-. (2015). An Inventory of Misuses of Democracy in the Western Balkans. ELIAMEP Working Paper No. 70. Athens: Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy.

Starcevic, B. (2022, 8 April). Pro-Russian Strongmen Win Re-Election in Hungary, Serbia. IR INSIDER. https://www.irinsider.org/easterncentral-europe/2022/4/9/pro-russian-strongmen-win-re-election-in-hungary-serbia

Taggart, P. (2004). Populism and representative politics in contemporaray Europe. Journal of Political Ideologies 9(3): 273–275.

Telegraf (2017, 6 July). Ko i zašto napada Vučića sada kada ima najveću podršku naroda? (Eng. Who and why attacks Aleksandar Vučić now that he has the highest support of the people?). https://www.telegraf.rs/vesti/politika/2866665-ko-i-zasto-napada-vucica-sada-kada-ima-najvecu-podrsku-naroda

———-. (2016, 21 September). PROCUREO RATNI SCENARIO ZA NAPAD NA REPUBLIKU SRPSKU: Ovako armija BiH planira da je osvoji (Eng. War scenario for attack on Republika Srpska leaked: This is how the Bosnian army plans to conquer it). https://www.telegraf.rs/vesti/2368002-procureo-ratni-scenario-za-napad-na-republiku-srpsku-ovako-armija-bih-planira-da-je-osvoji

The Guardian. (2016, 24 June). UK votes to leave EU after dramatic night divides nation. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/jun/24/britain-votes-for-brexit-eu-referendum-david-cameron

Tony Blair Institute for Change. (2017). European Populism: Trends, Threats and Future Prospects. https://institute.global/policy/european-populism-trends-threats-and-future-prospects

Urbinati, N. (2019). Political Theory of Populism. Annual Review of Political Science 22: 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-050317-070753

USA for UNHCR. (2016). Refugee Crisis in Europe. https://www.unrefugees.org/emergencies/refugee-crisis-in-europe/

USA Today. (2016, 14 July). More than 75% of terror attacks in 2016 took place in just 10 countries. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/world/2017/07/14/terrorist-attacks-2016-isis-10-countries/480336001/

Vesti. (2016, 20 September). “POSTOJI NAMERA DA SE RATOM UNIŠTI REPUBLIKA SRPSKA”. https://www.vesti.rs/Ivica-Da%C4%8Di%C4%87/Postoji-namera-da-se-ratom-unisti-Republika-Srpska.html

Vučić, A. (2019, 10 July). Elita i plebs. Politika. https://www.politika.rs/sr/clanak/433411/Elita-i-plebs

WDR. (2021, 28 October). Povlačenje Republike Srpske iz državnih institucija BiH. https://www1.wdr.de/radio/cosmo/programm/sendungen/radio-forum/region/rs-bih-kriza-100.html

Written by:

Admir Čavalić – PhD student at University of Tuzla, is economic analyst and the founder of Association Multi in B&H.

Haris Delić – MA in law studies, is a Senior Officer at University of Tuzla and member of Association Multi in B&H.

The article was originally published in The Visio Journal No. 7.

Continue exploring:

Slovak Government Continues to Forget about Poorest Citizens