Poland will mark twenty years as a member of the European Union in 2024. In recent years, eurosceptic sentiments undermining the benefits of European integration have gained ground in Poland and Europe.

However, the facts contradict these claims: membership in the European Union benefits member states. This is also true for Poland, which will continue to benefit from remaining in the Community, even if it eventually becomes a net contributor.

Real Benefits of the Union

In public debate, the benefits of EU membership are primarily associated with the subsidies that Poland receives. However, the most significant for the Polish economy is the access to the common market, which is based on the four freedoms: the free movement of goods, services, capital, and people. This stems from the fact that free trade is a positive-sum game – all participants can benefit. This is achieved through the specialization of individual countries or regions, the development of labor divisions, and the ability to shift production to more profitable locations.

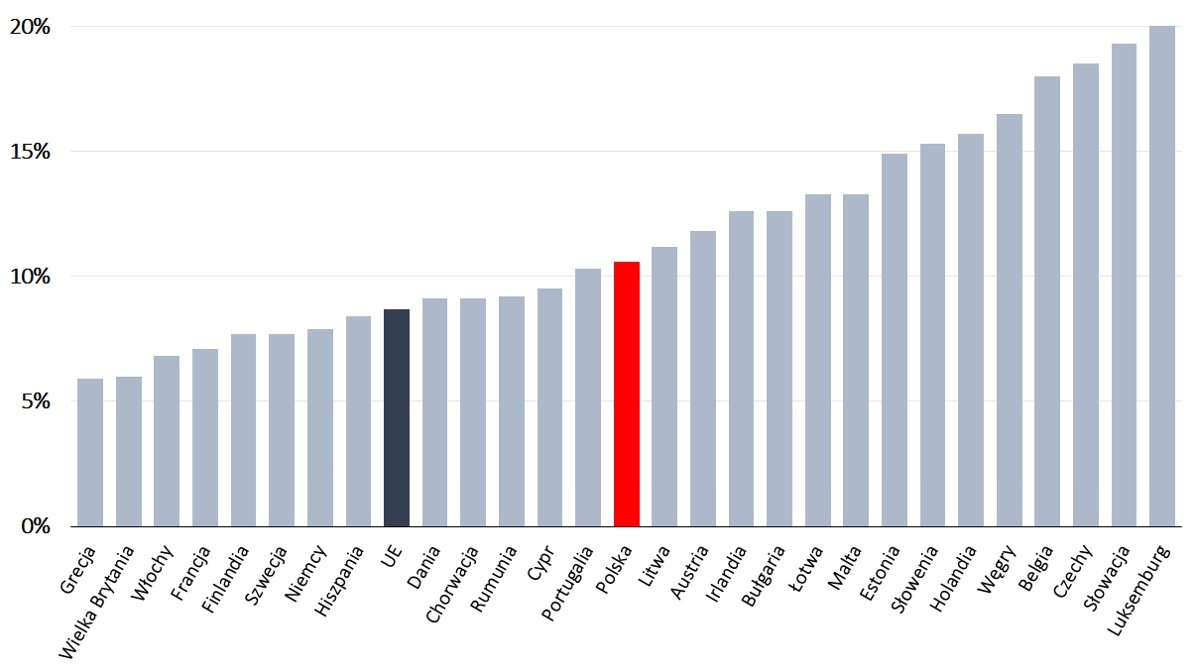

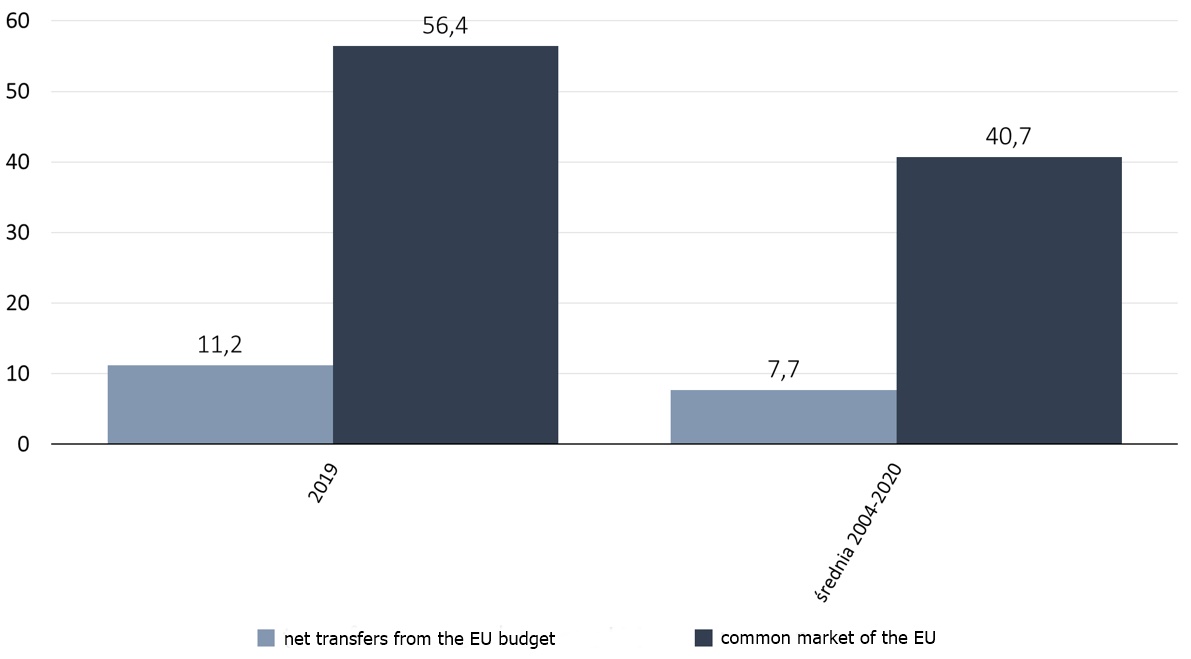

As Jan in ’t Veld points out, all EU member states have gained significantly from the common market (Figure 1). Poland gains five times more from access to the common market than from EU funds (Figure 2). Without the elimination of tariffs and other barriers, EU countries’ GDP would be, on average, 9% lower, and Poland’s GDP nearly 11% lower.

Figure 1. Benefits of Membership in the Common Market as % of GDP

Figure 2. Poland’s Benefits from Net Transfers from the EU Budget and the EU Common Mar-ket (in billion PLN)

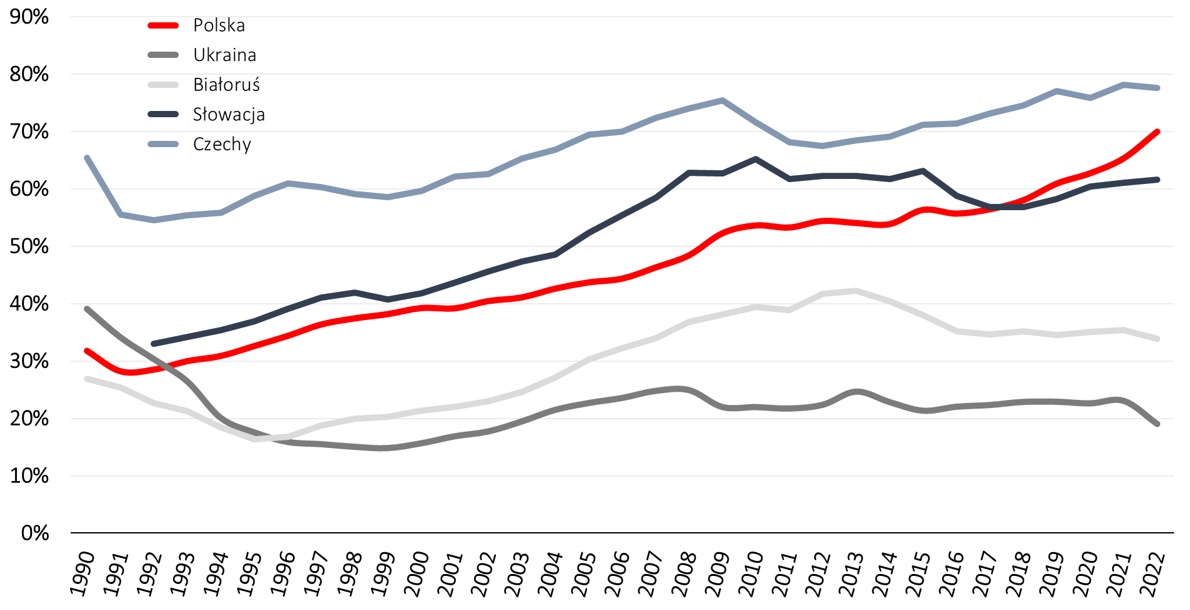

The systemic transformation and reforms initiated by Leszek Balcerowicz set the stage for the convergence of the Polish economy with the West. However, this modernization effort, rooted in economic liberalization, might have been squandered without the prospect of EU accession (examples include countries like Ukraine or Belarus that lacked such prospects).

Research shows that EU pressure supported economic liberalization and the development of the rule of law. When considering these institutional variables, Hagemejer, Michałek, and Svatko estimate that after 15 years of membership, Poland’s GDP per capita was over 50% higher than it would have been had the country not joined the Union. The EU expansion proved to be another source of wealth for former Eastern Bloc countries (Figure 3).

Figure 3. GDP per Capita PPP of Central and Eastern European Countries as % of Germany’s GDP per Capita PPP

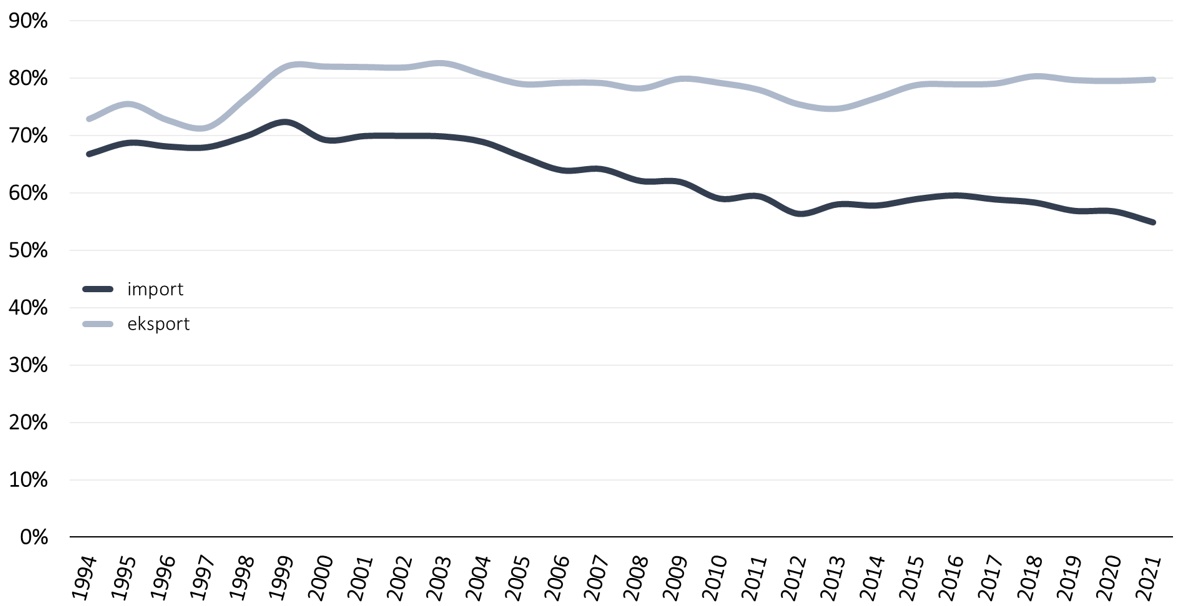

The removal of barriers in international trade has benefited Polish exporters and importers, as well as ordinary citizens who can purchase foreign products at lower prices. Even before the 2004 accession, trade with EU countries played a dominant role in international trade (Figure 4). Exports remain one of the main drivers of economic growth in Poland.

Figure 4. EU’s Share in Polish Trade

The common market also includes the free movement of people, which benefits both Poland and its citizens. Migration has helped reduce unemployment in Poland and created opportunities to export Polish products abroad. Moreover, these migrations often involve acquiring experience and knowledge (through work and study) that can be utilized upon return to Poland.

What About Regulations?

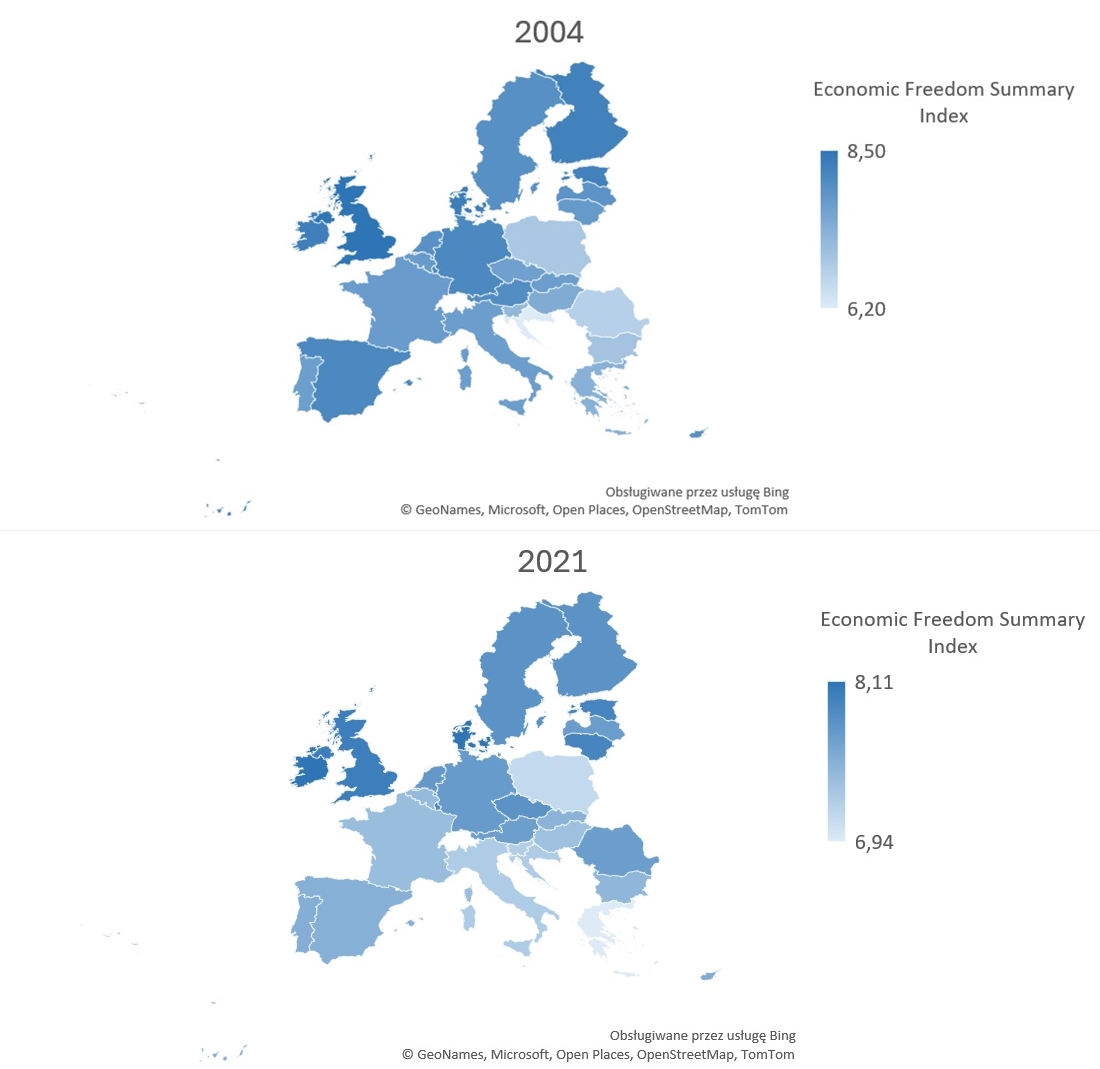

Critics often highlight the problem of EU regulations. However, an analysis of the Fraser Institute’s Economic Freedom Index reveals that member states exhibit diverse levels of economic freedom (Image 1). A certain convergence is noticeable, as the range of scores decreased from 2.3 in 2004 to 1.17 in 2022. This convergence has an important advantage: increased openness to international trade. The EU includes both ranking leaders (e.g., Ireland, Denmark, Estonia) and countries occupying lower positions (e.g., Greece, Italy, and Poland). This shows that Poland still has considerable room to expand economic freedom within the EU framework.

Image 1. Economic Freedom Levels in EU Countries

Eurosceptics, in their critique, often overlook the purpose of EU regulations. Harmonization of the single market often aims to reduce regulatory protectionism by individual EU states. This requires uniform regulations or mutual recognition of standards to allow products from one part of the common market to be sold freely in others. Nonetheless, protectionism remains a challenge for the EU. In defending interest groups, individual countries take actions that undermine the values of European free trade. The solution lies in building a broad liberal coalition to defend free trade, rather than advocating similar methods domestically or even leaving the Union.

In recent months, criticism of the EU has focused on the European Green Deal and climate policies. Once again, critics fail to recognize that other countries also plan to implement similar climate policies. Once again, the solution is liberalism: creating conditions in which the market and private initiatives develop environmentally friendly solutions and innovations.

Reforms Are Still Needed

Poland’s two decades of EU membership have been highly beneficial – regardless of the inflow of EU funds. There remains significant potential for development that can be unlocked through liberal reforms. Hopes that Poland could become a free-market champion after leaving the EU are misplaced – the scope of economic freedom in the UK has not increased post-Brexit. It is even more naive to believe this could happen in Poland, which ranks low in economic freedom within the EU.

A key challenge may be the declining significance of the European Union in the global economy. Howev-er, this challenge could be transformed into an opportunity for growth if it becomes a stimulus for further liberalization, unlocking the full potential of the Old Continent.

Written by Mateusz Michnik – FOR Junior Economic Analyst