The tax system has a profound impact on a country’s economic growth for two reasons. Firstly, in developed countries, taxes typically amount to the equivalent of one-third to even half of the GDP. Such a high level of taxation affects taxpayers’ economic activity. Secondly, for the state to collect taxes, it must maintain appropriate regulations defining the tax base (what to tax) and rates (how much—as a percentage or as an amount—must be paid from a given base).

These regulations influence decisions regarding, for example, the form of contracts between individuals, the legal form of business activities, or how savings are invested. Moreover, the complexity and variability of the rules generate additional uncertainty for payers concerning whether they must pay a tax at all, and if so, at what rate, as well as whether their situation might change in the near or distant future.

The overall level of taxes (taxation in relation to GDP) depends primarily on the size of government spending—although states also derive income from other sources, such as owned assets, and incur debt to cover deficits. It is not possible in a market economy to finance all public expenditures this way, which often reaches 50% of GDP. Without addressing the expenditure side, it is therefore impossible to reduce the overall level of taxation.

However, tax regulations can be changed without reforming expenditures. A well-designed tax system allows taxpayers to easily calculate and pay their dues and provides funds to finance public expenditures. Conversely, a poorly designed tax system is a burden on taxpayers and discourages them from productive activities, such as working and investing.

What negatively distinguishes Poland from other countries is not so much the level of taxes, although it has significantly increased in recent years and is higher than the OECD average, but the lack of neutrality, complexity, and variability of the system.

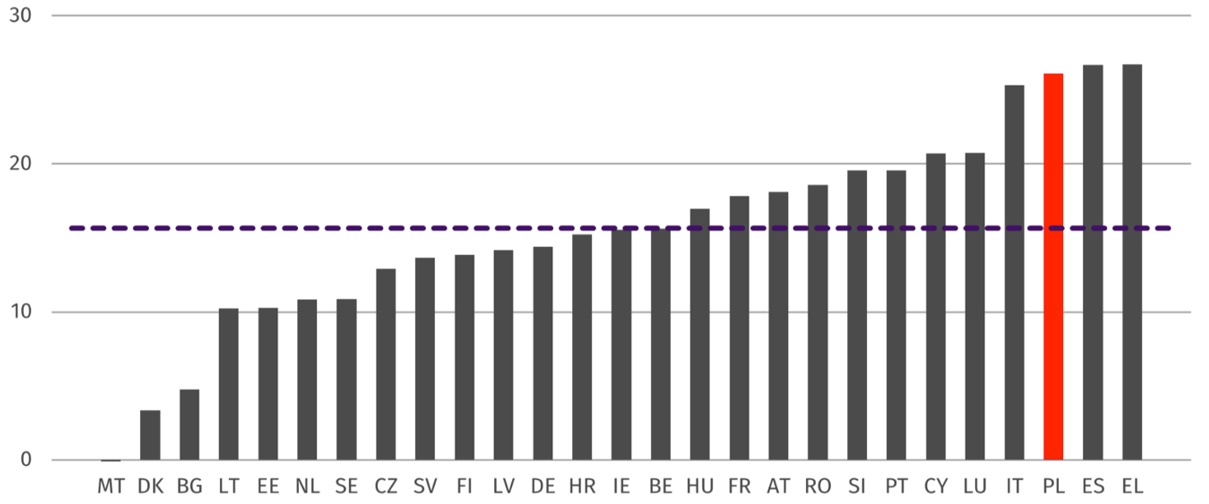

One of the key problems is the lack of system neutrality, which favors or penalizes selected industries or companies. The differentiation in VAT rates may serve as an example. In 2020, according to estimates of the Centre for Social and Economic Research, VAT revenues were over 26% lower than potential revenues due to the use of reduced rates and exemptions, while the average for the EU was 15.7%.

Figure 1. Lost VAT revenue as a result of applying reduced rates and exemptions as a percentage of potential revenue. Source: CASE

In recent years, the Polish tax system has seen the introduction of various sector-specific taxes such as the bank tax, mall tax, and retail sales tax. These taxes were implemented under the pretext of compensating for lost income tax revenues due to alleged tax avoidance practices in these sectors, however without presenting any analysis to confirm the scale of this phenomenon.

Another significant issue is the complexity of the Polish tax system. Countless tax reliefs, preferences, and sector-specific taxes not only complicate the lives of entrepreneurs but also increase the cost of doing business. The World Bank’s Doing Business report indicated that in 2018, fulfilling tax obligations in Poland required as much as 334 hours, placing the country in a very poor second place in the EU in this regard. Furthermore, a report prepared by VVA and KPMG for the European Commission shows that the total cost of fulfilling tax obligations in Poland is the second highest in the EU relative to sales revenue.

All this is compounded by the instability of tax regulations. Frequent changes in the rules generate uncertainty, which discourages long-term investment. Often, significant changes to tax regulations were passed in November, i.e., less than two months before they came into effect on January 1 of the following year.

This was the case, for example, with the so-called Polish Deal – the laws that were to come into effect on January 1, 2022, were signed by the president on November 15, 2021. The process of public consultations for this wide-ranging tax reform was surprisingly short. Originally, consultations were to last only 14 days. This decision met with widespread criticism, as it did not provide enough time for thorough analysis and discussion of the proposed changes.

Consequently, the consultation period was extended to 35 days, during which the government received 80 often highly critical opinions totaling 840 pages, signaling that the reform project could be legally flawed. The document in which the government very generally addressed the submitted comments was only 10 pages long, which in turn attested to the indifference of critical voices by the creators of the changes.

After the government experienced the scale of the chaos of the reforms, which experts and representatives of business organizations had warned about, it began patching the so-called Polish Deal with regulations that were lower in the hierarchy of legal acts than the acts introducing the tax reform. Then, work began on the so-called Polish Deal 2.0, which entailed further changes and confusion. Mid-year, three methods of collecting advance payments on personal income tax were permitted.

The consequence of this chaos was also huge overpayments, as a result of which in 2023, taxpayers received the highest tax refund in history, which the government tried to propagandize as its success – billboards across the country read: “Thanks to the government’s PIT reduction, millions of Poles received a tax refund.” However, these refunds were a result of previous overpayments, which in the conditions of double-digit inflation were interest-free loans taken by the state from taxpayers.

Solutions for the Polish tax system should aim to increase its neutrality, simplicity, and stability. This means eliminating numerous reliefs and preferences, abandoning sector-specific taxes, simplifying the system of calculating and collecting taxes, and reducing the system’s oppressiveness. It is also necessary to increase the standards of public consultations when introducing tax changes and to extend the vacatio legis period to give taxpayers more time to adjust to new regulations. If the government wants to encourage Polish companies to increase investment, which is crucial for economic growth, it must take actions that will make the Polish tax system more taxpayer-friendly.

Continue exploring:

How PiS Regulated Lives of Poles

Freedom and the Trap of Identity Politics with Yascha Mounk [PODCAST]