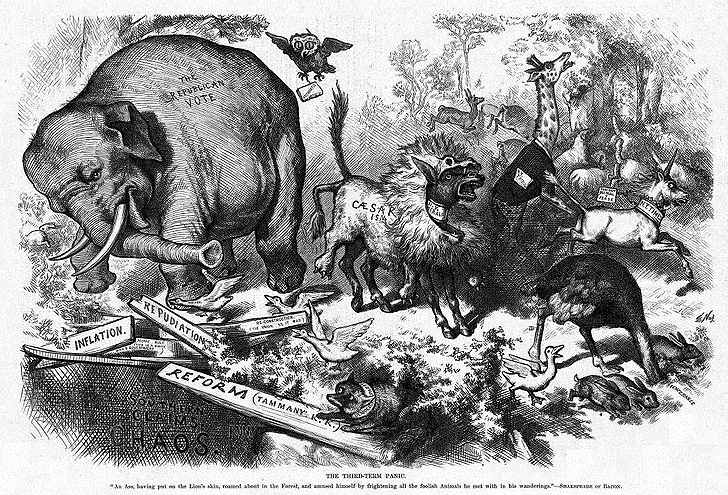

“Never use the language of the other party. For their language imposes their frame.” And if this frame is constituted by the concept of an elephant, it will weigh you down with its immensity, and your objection will only feed the beast and add it power. What may a liberal democrat say standing face to face with a several-tonne giant? That it grew too big? That its power disturbs the fragile social balance? It is all true, but the more we talk about it, the more people will notice that an elephant has the power which is probably worth following.

Elephants are mighty animals, and language is a tool determining politician’s power. Our manner of speaking may become a source of political power. It may also cause that we will become an elephant in a china shop. A thick-skinned animal that does not notice its strength and destroys everything around.

However, the reference to an elephant in reflections in what way the language shapes our political reality does not only stem from a network of metaphorical associations I have outlined in the introductory paragraph. The association of elephant’s power with the force of expressions we use came to my mind after reading a book by George Lakoff entitled Don’t think of an elephant, in which the American linguist presents characteristic features of conservatists’ and democrats’ language. However, the book by Lakoff is not a cold academic analysis of the language function in politics, but rather a warm guidebook in which a prominent professor of the University of Berkeley tries to show democrats a path to victory. In the period when Lakoff worked on this book, it could be thought that the conservatists mastered the indisputable receipt for success in subsequent elections. The directive “Don’t think of an elephant” formulated by Lakoff in the title (despite a direct reference to the Republican Party, whose coat of arms represents an elephant) sounds as abstractive in the context of the political rhetoric lesson as the idea of the American democrats’ victory. The book was published in 2004, that is in the moment when democrats were badly defeated in the elections. Thus the book, prepared as a kind of diary of political engagement of a prominent linguist in the electoral campaign, became a signpost for the democrats how to overcome the collapse, which the opposition usually feels after yet another lost elections.

The elephant from the title may be treated as a figure of auto-irony. On the other hand, in the immensity of its physicality it turns reader’s attention to the down-to-earth pragmatics. For in this peculiar guidebook of political speech Lakoff tries to combine transitory ideas and ideals with a tangible effectiveness of language utterances. This is why at the very beginning he voices a firm order that a reader has to stop thinking about an elephant. In the next sentence he explains that no one has ever managed to fulfill this prohibition. For a while attempting to obey this prohibition, we think intensively about not thinking and thus the idea of an elephant gets strengthened in our mind. It is due to this very mechanism of our brain operation “we should not use the language of the other party.” Using the words of our opponents we force our listeners to think in accordance with the values we are trying to undermine. If, for example we try to describe the essence of the modern-day “family crisis,” it is very difficult to escape from a conviction being put to our heads by the word “crisis” that the undergoing changes in social relations aim at solutions that are absolutely negative. In order to make people not afraid of the forthcoming new reality we need to propose a different manner of describing those changes. In other words, to change the reality, we need to change our language.

These are the tasks that Lakoff defines for himself, and his book is a compendium of a new language of American democrats. According to the diagnosis by the lecturer from Berkeley, conservatists have dominated the public language, efficiently covering their values in popular expressions, making it at the same time the binding social discourse. In what way can the compendium of American democrats’ rhetoric written almost ten years ago be helpful to a Polish reader? Jacek Wasilewski, the author of the introduction to the Polish edition of Lakoff’s book remarks that the book was published in Poland “in a very good time and it is at least inspiring.” Such a general view of the values of Lakoff’s work reduces his book to yet another manual of political persuasion art. For an American reader, its characteristic feature is the methodological ordering of language, which efficiently conveys American democrats’ ideas. For a Pole reading the book as political instructions, it remains mainly a collection of interesting examples, some of which have often already died away, and some not clear enough.

Let us have a closer look at the strategy of attributing democrats “an ugly face” described by Lakoff. This was done by conservatists, who thanks to “a few dozen years of work of their most prominent intellectuals, experts in language, writers, advertising agencies, and media experts made” people start thinking about liberal democrats as an elite party, separated from everyday life problems of an average man. In order to create such a negative image, representatives of the Democratic Party started to be called: “Hollywood liberals, limousine liberals, or latte liberals.” The mechanism of using the language to create a distance between the Democratic Party and its potential electors is here absolutely clear. Nevertheless, in the context of modern political life in Poland, negative expressions used to describe liberals seem to be merely cutting remarks towards political opponents. Comparing the results – as Lakoff emphasises – of “several dozen years of work” of the best American specialists with the productivity and colourfulness of modern-day language of Polish politicians, one may come to a conclusion that the results of the creativity of American experts in political marketing fade when juxtaposed with the imagination and vigour of our national language “producers” and engineers of social imagination. Expressions well-known to Poles as for example: “freaks,” “porno fatties,” “mohairs,” “lumpen-liberals,” “lying elites,” “educationians” surely constitute a much more intriguing material revealing the potential of human imagination and the vitality of political language. The examples quoted above may be of course treated also as proofs of the lack of moderation or even political degradation. However, irrespectively of the assessment of the language of Polish politicians, we have things to ponder over in our own country and we do not need to look at fellow democrats in America. Perhaps it may be so that the academic moderation of Lakoff makes that slogans he refers to not as strong as utterances of some Polish politicians. However the book Don’t think of an elephant has some potential that has made me spend on it more time than a normal reading would require.

A lecturer is hardly ever a good copyrighter. This is why the examples of reasoning presented by Lakoff seem to me not very interesting. The idea of framing, which can be presented in a simplified way as imposing your definitions of situations to your opponents, is very coarse (though efficient in the art of persuasion) in comparison with the concept of metaphor developed by Lakoff in his academic works. The main contribution in this aspect of knowledge about our language was to point to several underestimated (not noticed) dimensions of the metaphorisation process. First of all, according to Lakoff the metaphor is not limited to exceptional expressions, but it functions in everyday usage. It is so common that often we tend not to notice it in our colloquial language. Secondly, the metaphor is not only a domain of poetic imagination but it undergoes classification creating a coherent and practical manners of comprehending/expressing the reality.

Similar observations may be applied to the processes of framing. On the one hand we deal with imagination fireworks of spin doctors or other masters of linguistic manipulation. On the other, our everyday language is filled with “innocent” formulae that seem to be almost transparent but their influence on our manner of thinking and system of values is considerable.

A representative of the first kind of creativity in Lakoff’s book is for example the “death tax” slogan introduced by the conservatists. It appears each time when the issue of taxing the inheritance is discussed and it efficiently moves rational arguments to the background. The “death tax” is not only an expression that adds the negative dimension to the issue of taxing the inheritance, but also reducing it to something unpleasant or even immoral. When in Poland we sometimes speak of the necessity to make it clear that we are not camels, the above-mentioned frame forces the supporters of such a taxation to explain themselves that they are not scoundrels or grave robbers. Everyone prefers to stay away from such “pleasant” situations.

For me personally, a much more surprising reference to the source of framing of the manner of thinking about our financial liabilities towards the state was such an obvious expression as “tax burden” or its positive counterpart “tax benefit.” Focusing on this second phrase, Lakoff discovers quite an obvious truth that speaking of tax benefits implies the existence of some unpleasant burden. A man touched with this distress waits for a hero to save him from this uncomfortable situation. And he treats each person to increase the tax rate “as a bastard who tries to render the comfort impossible.” In the positive part of his argument, Lakoff tries to re-frame the thinking about taxes showing how to talk about taxes as a good investment, as a necessary contribution, etc. I find the affirmative concept of taxes not convincing, but this is a topic for another discussion. What is most important is the fact that Lakoff teaches us to look attentively not only where we find noise and colourful clowns, but also to observe these spheres of language which on everyday basis create the illusion of innocence.

The second discovery of the American linguist was the concept of the regularity and coherence of the language of metaphors, and as a result, of frames that are often (as you have probably already discovered) metaphors. The frame grows into a complex system of images that create a logical whole. What is important, this logic does not stem from a kind of imperative, but it is the property of our mind, which often ineptly but consequently aims at coherence of concepts (or at least cognitivists teach us so).

Due to this, Lakoff manages to draw a clear difference in the way of thinking about the state and society that is characteristic for conservatists and liberals. Generally speaking, conservatists’ manner of thinking about the state develops according to the frame of a “severe father.” It assumes that the state (the government or other governing bodies) perform the role of a severe father, while citizens can be divided into good and bad children. Those who are properly accustomed to life pay taxes and contribute to the general growth of welfare. The bad persons should be punished for not contributing enough to the development of the community. Citizens-children are brought up by the conservatists according to peculiarly understood Biblical rule that “whoever has will be given more and whoever does not have, even what they have will be taken from them.” The image of a severe parent stretches much further on all spheres of the state activity. The strict father is also a hard defender of the family, who not only revenges on those who made harm to individuals under his protection, but also he can, and as a father is fully entitled to do so, foresee the danger and attack in advance. For his children (citizens) he is also an embodiment of an ideal, a model to look upon for his family as well as other people. According to this frame, the president of the USA is also a father responsible for the whole world, which, to put it in a simplified manner, is divided into developed western countries and countries that have not yet matured and still remain children. If it is so, then according to the conservative vision of a family, those children have to be brought up using punishment and encouragement. For the world is generally speaking dangerous, and children are born weak and bad, which is why it is necessary to make them good citizens of our world.

Lakoff juxtaposes this image of the state so firmly anchored in our mind with the democratic-liberal vision of a protective and compassionate parent. The task of the parents (let me repeat of both parents) in this model is “the protection of children and bringing them up in such a way that they themselves will become good protectors. The protection involves two aspects: empathy and responsibility (for oneself and others). Empathy means that we want for others protection against harm, fulfillment in life, honesty, freedom, and open and two-directional communication.” On a general level, this model seems to be an attractive counter-proposal to the conservative model of a strict father. As a liberal, I find particularly close those passages, in which Lakoff writes about mutual responsibility, sincere, mutual communication, or the community of people who are given rights, but also mutual responsibilities (responsibility for others).

What is extremely important is also the remark that the possibility of helping other people requires taking care of one’s own affairs. However, in the concept of community as promoted by Lakoff, the image of parents who bring up their children in a responsible manner is recurring. It is obvious that models of young generation upbringing constitute an essential social issue that is worth tackling upon in ideological speeches. However, how does it relate to the establishment of proper relations between the state and its citizens? One may say that in Lakoff’s description the upbringing of a child appears as an element of the holistic understanding of a family model. His own lectures teach us that the logic of metaphors and frames is different. Relations between parents and children that constantly are referred to as model ones make this frame important for our perception of the state reality. In other words, the state stands for parents, and its citizens are children, which results in particular duties of either party of such a system. On the basis of the concept of a responsible and compassionate parent Lakoff derives the totality of left-wing programme, obliging the state to provide its citizens with health care, security, access to knowledge and information, the possibility to use the infrastructure, and even the knowledge how to be happy and fulfilled.

The above-mentioned examples of the state obligations towards its citizens seem to be justified in their totality. But the thing is that conservatists agree with many of them, suggesting maybe a different manner of acting, but still increasing at least partial responsibility of the state for the enumerated earlier spheres of social life. In what way do the American democrats differ from the American conservatists? The text by Lakoff states that key frames that make the difference include compassion and responsibility. Here we come back again to parents, as examples given by Lakoff freely intertwine the state obligations with those of parents. All values relevant in the process of upbringing (sic!) stem from the already mentioned frames created by the concepts of compassion and responsibility. Thus, for example “if you take care of your child, you protect it. Against what do you protect them? Surely against drugs and crimes. You also try to protect your children against driving a car without seat belts, against smoking, or toxic substances in food. Such a behaviour – according to Lakoff – enters politics in many ways, in the form of environment protection, employees’ and consumers’ protection, and protection against diseases.” In the quoted passage of the book Don’t think of an elephant, Lakoff confirms that relations between the state and its citizens are shaped by the notion of parents responsible for their children. However, this way of thinking does not correspond to the previously drafted frame of society consisting of citizens mutually responsible for one another. In other words, the partner model based on mutuality has its limits, which is revealed to us by the order of frames and metaphors used by Lakoff.

A compassionate parent does not suddenly stop the car so that his kid riding without a seat belt would harm himself and learn his lesson, such a parent will rather encourage his child to fasten it, and as a responsible parent he will not start the car until the child fastens his seat belt. I would like to make myself clear. In the case of small children, the responsibility to make sure that their actions are safe lies with parents.

However, citizens are not children and here is the point were the paths of Lakoff and people considering themselves as democrats go apart. One of the most important reasons for my dealing with the concept that Lakoff presented in his book Don’t think of an elephant is the fact that reading it made me aware of the one of the most basic differences in liberals’ way of thinking as juxtaposed with the way of thinking of conservatists and left-wing politicians (American democrats). Before I pass onto the presentation of the most basic conclusions, I would like to bring our attention to our national situation. The origin of this texts only partially stems from the reflections of the American linguist. The second source of my inspiration is the work of Łucja Iwanczewska – my colleague from the faculty. Describing the figure of Polish child-hero in the Polish culture of the 19th century, she summarises her reflections with an image that constitutes a diagnosis of the approach of Polish society towards reality and simultaneously pointing to its sources. This image is the traditional Polish nativity scene that penetrates our culture, both its high registers and everyday life sphere.

The leitmotif, which becomes a guide to the history of Polish fascination with the nativity scene in Iwanczewska’s text is the work by Lucjan Rydel Betlejem Polskie, about which a reviewer of “Gazeta Lwowska” wrote in the following way at the beginning of the 20th century:

“This work of enormous simplicity and sincere poetic inspiration is characterised with an unspeakable charm coming from a cordial Polish heart! It carries a viewer with the charm of words of a naive carol into his calm, angelic childhood, it presents him a splendid past of his nation, and further on all pains and all tears, and all defeats until the present day…”

The show written by Rydel warmed up Polish hearts throughout the whole 20th century, which was so difficult for our nation, to become after 1989 – as Iwanczewska emphasises – almost an obligatory show, “staged in every voievodeship. Thus Poles gained an opportunity to take part in a big national ritual, during which in front of the manger there are all Polish heroes, who give Jesus national souvenirs and symbols of fights.” The meaning of this march of Polish history in front of Baby Jesus is well explained by the words of one of the heroines, a citizen of the Grand Duchy of Posen, who says:

“The whole Poland with all its heroes finds refuge under the Mother’s coat, under the wings of the white eagle and stands face to face with Baby Jesus.”

For Iwanczewska, the procession of Poles to the manger becomes a practice confirming the state, in which “Poland as well as its heroes are, just as children, a project not yet finished, not yet closed (…). They are still waiting for adulthood that is not coming. Instead there is another regression that comes, another return to childhood.”

The conclusion formulated in such a way may refer to a transitory period, in which Poland finds itself unfortunately for over a century. However I think that this what Iwanczewska rightly recognises as one of the characteristic features of Poles is at the same time a mechanism quite common in other democracies, though may be not so clearly visible. Other nations also desire commanders, supernatural caretakers, fathers, leaders who will take over the responsibility. For being a child is quite comfortable and clever. It does not exclude the possibility of doing great, heroic deeds, but it does not oblige to bear responsibility for the results of our daily actions. If needed, we can always count of the intervention of an parent or at least his understanding.

On the other hand it is not that profitable. The frame of a parent, regardless if we speak of strict or protective parent, gives the state tools and right to “bring up” its citizens. It does not matter if the governing bodies act according to the rules of severe or compassionate father, in both cases they gain an exclusive right to decide what is good and safe for the citizens. For driving a car without fastened seat belt we may be punished with fines or encouraged to drive safely by means of various encouragements or teachings. However in the two cases we are put in a position of people who do not know, who have to be brought up, taught, or forced. Such a situation is an obvious attack on our freedom and dignity. However, it is not the end of the results of thinking with the application of the frame established by the relation parent-child.

The postulate of the necessity to bring up citizens condemns them for dumbness. Someone who does not know may speak, but his speech is of no significance. In such a situation the enlightened idea of mutual and sincere communication declared by Lakoff is not feasible. How may one speak of mutuality, when one of the parties is refused the right to present their arguments? In this very moment the coherence of the “family frame” of a caring parent promoted by Lakoff is destroyed. And the consequences of this destruction are not limited only to its identification within the analysis of the model proposed by Lakoff.

The idea of a father (parent) who teaches, knows better, is responsible, and listens to his child, but only in order to rectify thus naive, sometimes dangerous ideas leaves a deep mark in the practical functioning of political life in Poland (also in other countries). Of course, one cannot point to the centre of parental power as it depends on the person who is trying to define it. On the other hand it is not difficult to point to, at least partial, list of pretenders to the role of tutor of the nation. First of all, among different political options overusing the expressions “freaks”, “educationians”, “mohairs” etc. The mechanism of “patronising” society is much more visible in the division of the centre and province, in refusing people from poorer regions the right in discussions over methods of solving the problems of the Polish state. One does need to mention the still existing division into urban centres, middle class, or province inhabited by “groups that do not follow up.” And it is of no importance if we offend our opponents with the use of ideological epithets or if we bend over the hurt ones with care. In both cases we treat them as naughty or immature children that we may listen to but we do not need to take care of their words. After all, according to the slogan repeated for many years, “Poles are still not mature enough for democracy.” We should be all put under the protection of the severe father, whose role will best Bush Junior or of the good parent as suggested by Lakoff.

Paradoxically, the title of Lakoff’s book Don’t think of an elephant is a phrase pointing at the very centre of the idea of family community described in the book that is built on the basis of mutual responsibility and trust. The provoking formula on its cover is an introduction to a teaching, paternalistic in its character, not to speak (and by consequence according to the assumptions of cognitivism, not to think) with the language of our political opponents. Such an attitude constitutes however a base of fight for leadership, which on one hand reveals the patriarchal will of symbolic power over the entire society, on the other hand it paradoxically reveals childish fears against the acceptance of the fact of the existence of competitive models of reality. If we stop thinking of society as of a family, whose frames are defined by the relation parent-child, we will see that the scope of values created by the community goes beyond the duties imposed by the approach of compassion and responsibility, enriching us with respect towards other, which makes us not only more ethical people, but also stronger and more efficient. Regardless of the liking towards children, which is close to me, cooperation with adults is in the majority of cases much more effective. This is why we should never put anyone, even our opponents in the position of children. It is much better to live and think according to the metaphor, within which the state is a large family community of mature people who just differ from one another as it is normal in big families. Such a way of thinking about the state, in my opinion, differentiates liberals from both conservatists and left-winged politicians (democrats). But it is not because they perceive themselves as more mature but because they treat as mature both their sisters from the left-wing of the political scene as well as brothers from the right-wing. For it is better and more practical to think of an “other” as of an elephant that imposes on us frames that differ from our own that to refer to people who think in a different manner than we do with compassion proper to immature individuals or unhappy animals closed in the cages of their “mental limitations.” I appeal then: “liberal, don’t be afraid of thinking of an elephant!”