On August 9, Andrzej Duda signed the bill introducing the widow’s pension. The widow’s pension is intended to be a new way of combining a retirement pension and a survivor’s pension.

Previously, a widowed retiree could receive their own pension or 85% of their deceased spouse’s pension (the survivor’s pension). The widow’s pension allows beneficiaries to receive their own pension or survivor’s pension along with an additional 15% (rising to 25% by 2027) of the other benefit. Although this measure is less expensive than the original citizens’ initiative (the program’s ultimate cost is expected to be 11.1 billion PLN[1] instead of 26.9 billion PLN annually), it still adds a burden to public finances during a time of poor fiscal health and the initiation of the excessive deficit procedure[2]. This is yet another government program that worsens public finances in a flawed, discriminatory manner, creating additional problems.

In this sense, it continues the methods used by PiS (Law and Justice Party) in its social policy, focusing on programs aimed at a broad audience rather than those in real financial difficulty. Moreover, the widow’s pension mechanism itself is problematic, raising legitimate concerns about the discrimination against men and the need itself for widespread support of retirees, whose financial situation is not as dire as proponents of the widow’s pension would have the public believe.

Widowed Budget

When introducing another program aimed at supporting retirees, it is essential to consider the reality of public finances – expenditures on pensions have long been the largest category of public spending[3]. Poland’s pension system is both costly and inefficient, riddled with privileges and politically motivated patches like the “13th pension,” the “14th pension,” and now the widow’s pension[4]. A significant problem is the low and unequal retirement age.

Maintaining the current levels of 60 years for women and 65 years for men poses risks to public finances and the quality of life for future retirees. The unequal retirement age is a double-edged sword – while only 75.8% of men reach retirement age compared to 93.3% of women, women have to live with lower pensions than men[5]. Poland remains the only EU country with an unequal retirement age and no plan to equalize it [6].

Meanwhile, Poles have a distorted perception of the pension system’s functioning, underestimating the percentage of public expenditures devoted to pensions. According to a 2021 survey, respondents believed that only 15% of public spending was allocated to pensions, while the actual figure was 34%[7]. This situation allows public opinion to be manipulated and encourages the political fight for votes using new benefits for seniors. The same survey showed that informed Poles were more likely to support pension cuts rather than increases[8].

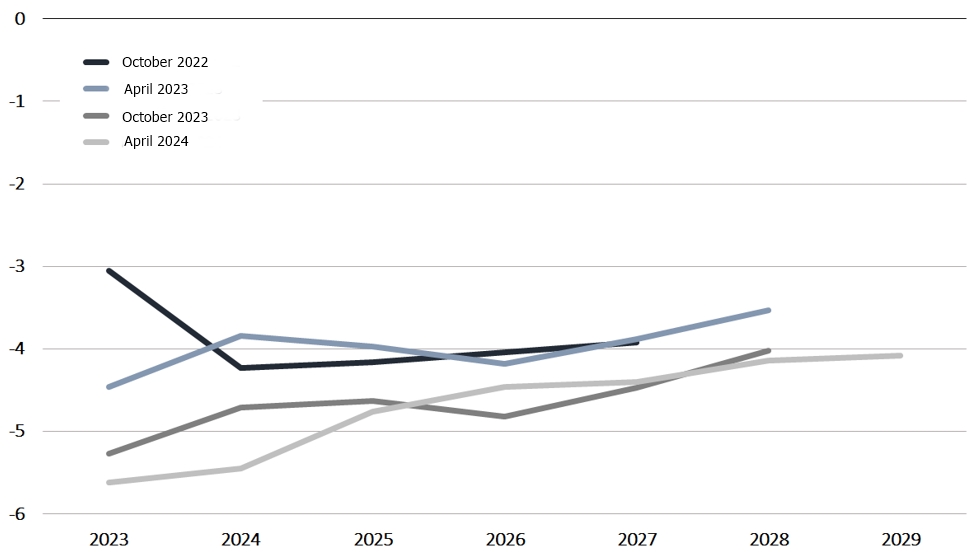

Although the program will be less costly than the original citizens’ proposal (just under 0.5% of GDP instead of 1% of GDP[9]), it remains an additional burden on Poland’s public finances, which are already among the most deficit-ridden in the European Union. Forecasts predict that deficits will remain above 3% of GDP for years (Figure 1) – the threshold for activating the excessive deficit procedure.

Figure 1. Public Finance Balance Projections as % of GDP

Myth of Poor Pensioner

Politicians propose these measures for a simple reason – excessive empathy. However, as in many other cases, relying on empathy (especially false empathy) in politics leads to harm and excessive costs[10]. Poles are seduced by the image of poor retirees who need generous support from the state budget. This leads to the acceptance of harmful solutions like pension privileges, the “13th pension,” and the “14th pension,” or a low and unequal retirement age.

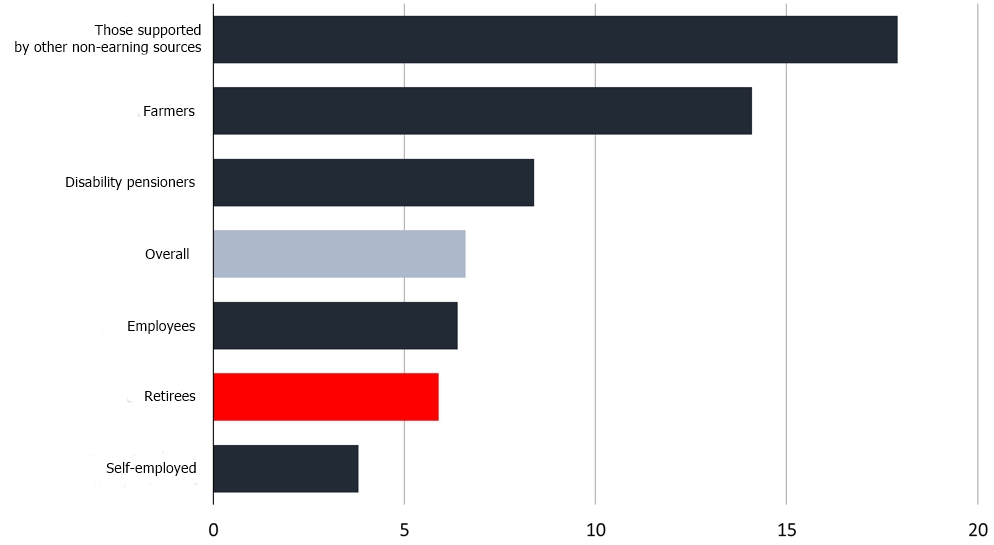

In reality, society’s perception of retirees’ standard of living is lower than it actually is. While retirees’ incomes are low, they are rarely at risk of extreme poverty (Figure 2). What is more, if politicians were genuinely motivated by helping others with public money, they should focus on younger individuals who are more at risk of extreme poverty. However, such solutions would not generate the same political support as gifting benefits to widowed retirees (or rather, mostly widows).

Even retirees living alone are not as threatened by poverty as working individuals[11]. Of course, they are relatively more vulnerable to poverty than retirees in marriages, but the widow’s pension does not solve this problem. Instead, it primarily benefits retirees receiving higher benefits due to the limits. The current cap of three times the minimum pension still appears too high for what is supposed to be supplementary support.

Figure 2. Extent of Extreme Poverty (%) in 2023 Among Retirees

What About Those Who Do Not Live to Become Widowed?

The widow’s pension also has other social drawbacks. In this regard, it is a continuation of PiS’s social policy – generous, politically motivated support reinforcing a conservative vision of family and society.

Firstly, by its nature, it discriminates against people in same-sex relationships, singles, and divorcees. In the latter case, it may even encourage staying in unhealthy or abusive marriages to retain future access to the pension[12].

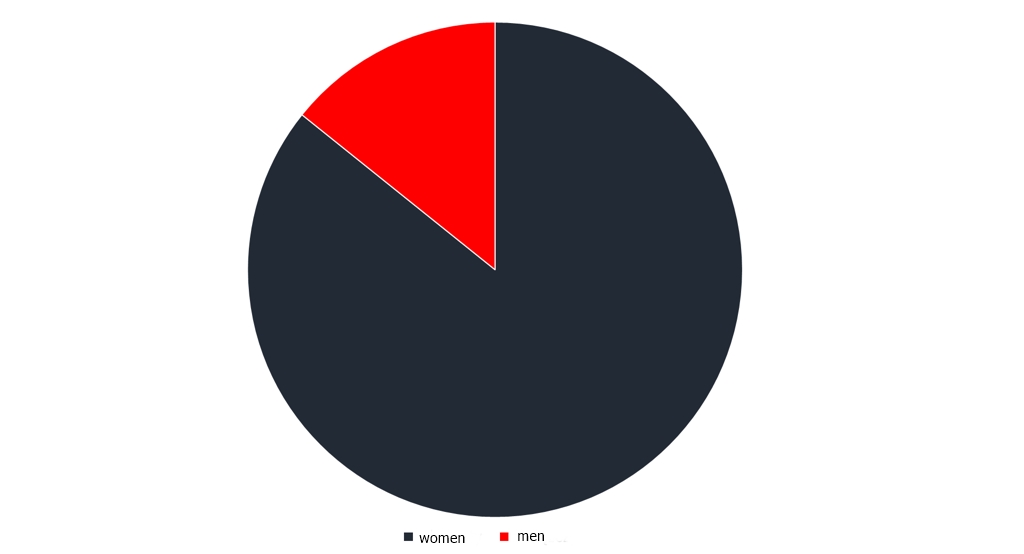

Secondly, the program discriminates against men – statistically, they live shorter lives than women. However, the widow’s pension would unequally entitle them to benefits: women could receive it upon being widowed at age 55, while men would need to wait until age 60[13]. This disparity, rooted in unequal retirement ages, further exacerbates inequalities – men will contribute even more to the pension system. Data shows that 85% of those eligible for the widow’s pension in 2025 will be women, highlighting systemic discrimination (Figure 3). Moreover, alternative solutions that could increase men’s lifespans, thereby reducing the issue of poor material conditions for widowed retirees, are ignored[14].

Figure 3. Eligibility for Widow’s Pension in 2025

Summary

The widow’s pension is yet another example of politically motivated public spending and ham-fisted attempts to patch up the pension system instead of carrying out comprehensive reform. The data suggests that retirees as a group do not live in conditions dire enough to justify additional benefits: they are no more at risk of poverty than the rest of the population, and a significant and growing share of public spending already goes to them.

Instead of considering prudent financial management, particularly during a budgetary crisis, the government opts for poorly thought-out patches to the pension system – patches that create further holes, such as increased inequalities between men and women in pensions.

References

[1] M. Myck, A. Król, M. Oczkowska, Renta wdowia: zmiany w systemie wsparcia wdów i wdowców uchwalone przez Sejm RP, CenEA Commentary, July 30, 2024, https://cenea.org.pl/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/rentawdowia_komentarz_cenea_30072024-2.pdf.

[2] M. Zieliński, B. Jabrzyk, The Bill from the State for 2023, Communication 18/2024, Civil Development Forum, June 25, 2024, https://for.org.pl/2024/06/25/komunikat-18-2024-rachunek-od-panstwa-za-2023-rok/.

[3] Ibidem.

[4] A. Suraj, System emerytalny w Polsce to chaos. Ta stajnia Augiasza wymaga posprzątania, Obserwator Gospodarczy, November 5, 2023, https://obserwatorgospodarczy.pl/2023/11/05/system-emerytalny-w-polsce-to-chaos-ta-stajnia-augiasza-wymaga-posprzatania/.

[5] J. Chabik, Wiek emerytalny – siedem argumentów za równością, Stowarzyszenie na rzecz Chłopców i Mężczyzn, March 15, 2024, https://schm.org.pl/blog/wiek-emerytalny-siedem-argumentow-za-rownoscia/.

[6] Ibidem.

[7] A. Kiełczewska, J. Sawulski, Postawy Polaków wobec płacenia podatków i roli państwa w gospodarce, Polish Economic Institute, Warsaw 2021, p. 17.

[8] Ibidem, p. 23.

[9] J. Misztal, Renta wdowia niewypałem? „Koszty nie do udźwignięcia”, Bankier.pl, July 18, 2024, https://www.bankier.pl/wiadomosc/Renta-wdowia-niewypalem-Koszty-nie-do-udzwigniecia-8783970.html.

[10] P. Bloom, Przeciw empatii. Argumenty za racjonalnym współczuciem, Wydawnictwo Charaktery, Kielce 2017, p. 127–142.

[11] K. Bech-Wysocka, J. Tyrowicz, Ubogi jak emeryt? Jak zmieniało się ubóstwo w Polsce i co nas czeka w przyszłości, Instytut Myśli Liberalnej, https://instytutmysliliberalnej.pl/ubogi-jak-emeryt/.

[12] P. Szumlewicz, Seniorzy lepszego sortu. Głos przeciwko rencie wdowiej, wyborcza.pl, August 1, 2024, https://wyborcza.pl/7,75968,31188830,seniorzy-lepszego-sortu-glos-przeciwko-rencie-wdowiej.html;

- Przyborska, Renta wdowia – taki sukces to porażka, KrytykaPolityczna.pl, August 5, 2024, https://krytykapolityczna.pl/kraj/renta-wdowia-taki-sukces-lewicy-to-porazka/.

[13] M. Krześniak-Sajewicz, Renta wdowia może dyskryminować mężczyzn. Ekspert wskazuje problem i apeluje do Senatu, Interia Biznes, July 30, 2024, https://biznes.interia.pl/emerytury/news-renta-wdowia-moze-dyskryminowac-mezczyzn-ekspert-wskazuje-pr,nId,7746792.

[14] J. Chabik, Renta wdowia? Lepiej jesień życia u boku ukochanej osoby!, Stowarzyszenie na rzecz Chłopców i Mężczyzn, July 12, 2023, https://schm.org.pl/blog/renta-wdowia-a-moze-jesien-zycia-u-boku-ukochanej-osoby/

Written by Mateusz Michnik – FOR Junior Economic Analyst

Continue exploring:

Instead of State Ownership in Economy: Investments Control, Golden Veto, Regulations

Your “Dream” House – Affordable Living Prospects in Hungary and Budapest [Conference Summary]