The article covers the perplexities of the internet governance multistakeholder model, its meaning and implications. While relying on the well-established reference to three principal groups of stakeholders (states, business, civil society), the chapter includes discussion on different approaches to internet governance and reflects on arguments against the current model of setting standards and norms for cyberspace.

It contrasts the existing model of governance with challenges posed by international cybersecurity and protecting human rights online. The case study example focuses on the most recent challenges posed to the multistakeholder model by the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and its implementation by non-European legal persons operating on Europeans’ data.

The analysis is focused on the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) – a non-profit based in California, managing core internet resources, including the Internet Protocol (IP) and the Domain Name System (DNS). It concludes with a summary of perspectives for future development of multistakeholderism, referring to contemporary trends in meta-governance.

Introduction

Internet governance relies on multistakeholderism – a distributed policy making model based on voluntary cooperation of key actors, usually identified as states, business and civil society, operating “in their respective roles” (WSIS 2005) through “rough consensus and running code” (Clark 1992; Huizer and Crocker 1994). This approach, although neither new or unique to cyberspace, significantly differs from national lawmaking or international norm development.

While in both of those scenarios it is states who play a key role, internet governance grants national governments and institutions only a complementary function in setting and enforcing “principles, norms, rules, decision making procedures and programs” for the global network (Drake 2009,8).

While a similar, supporting rather than leading, role for states can be witnessed in many other areas of international law and relations, just to mention environmental protection, oil transportation, production of pharmaceuticals or banking, where much is left to good business practice, civil society input and/or consumer choice, the interplay of governments, companies and individuals is nowhere more complex, abundant and transnational than online. Likely due to three factors:

1) the complexity and scale of online interactions, with 3,6 million Internet users worldwide in 2017 (ITU 2018);

2) the global monopoly of few U.S. based companies (often referred to as “GAFA”: Google, Amazon, Facebook and Apple); and

3) the gross value of the online market (estimated at 2.304 trillion USD in online transactions globally in 2017) (eMarketer 2018, online) the lines between the roles of stakeholder groups are nowhere more controversial and disputed than in the online environment.

While many still praise the network’s unique governance model as key to Internet’s boom and rapid development since the early 1990s that lead to shifts in the global economy and fundamental political changes across the world, existing multistakeholder model is far from ideal. Not only does it fail to identify particular rights and obligations of individual actors effectively, but, most significantly at the time of the global war on terror and increasing terrorist uses of the network, it strongly disables state institutions in performing their original roles as lawmakers and enforcers.

Much is being said about an alleged “lex Facebook” – a company policy that serves as a global law for billions of its users – particularly in the light of the recent (2018) Cambridge Analytica scandal, disclosing ways to effectively influence individual political choices by personal data profiling with the use of advanced advertising algorithms.

The lawmaking power is dramatically shifting away from states, who are desperate to regain it at a time of political and economic insecurity. In their attempts to do so, either in the domain of online security or global trade, they must consider the networks’ specifics: its architecture, design and, most significantly, the particular traits of its current multistakeholder model of governance, as discussed below.

Analysis

Governance – a term often used in reference to the unique Internet ecosystem – is neither new or unique to the global communication network. A recent, comprehensive anthology by Levi-Faur offers a versatile review of the rich array of contemporary policy areas subject to “governance”. They range from state reform and its democratic institutions to international organizations, global economic relations, labor relations, public health management, banking, risk management and environmental protection (Levi-Faur 2012).

In this context, Dutton refers to the Internet and its governance as “a Fifth Estate” describing how the Internet “is being used (…) in ways that support social accountability across many sectors” (Dutton 2012, 585). He refers to the power Internet holds over social relationships and political decisions, reflecting the eighteenth-century concept of Fourth Estate created by the press, now, as he alleges, substituted by the unique impact the Internet has on the global society.

While nearing on “a fuzzy term (that) can be applied to almost anything and (…) explains nothing” (Bygrave 2015, 12), Dutton’s take of governance focuses on the actual challenge Internet poses to existing regulatory mechanisms and reflects the versatility of its process and actors.

Yet, as Bygrave rightfully notes, the “nebulous and broad” concept of governance has been defined with other references, like those to “processes influencing other actors” or “the sum of the many ways in that individuals and institutions public and private manage their common affairs” (Bygrave 2015, 11-17).

While “governance” is often perceived as contrary to “government”, Bygrave views it as one of many methods of regulation. He sides with a “decentered” definition of the latter, covering more than just the activities of governments and state actors” (Bygrave 2015, 13).

Drake, on the other hand, offers an “action-oriented” approach to global governance, relying on its steering mechanisms or institutions rather than the actors behind them. He defines global governance as “the development and application of shared principles, norms, rules, decision-making procedures, and programs intended to shape actor’s expectations and practices and to enhance their collective management capabilities in world affair” (Drake 2009, 9).

This definition offers a good reflection of the complexity of actions and institutions behind contemporary global governance processes and seems best suited for the following discussion on Internet governance.

Distributed governance, operating on consensus among various groups of stakeholders is, as already said, not unique to the Internet model. As noted by Weber and Weber, particular analogies are to be drawn with environmental law, where individual rights, including the right to information and freedom of speech, in particular, the right to protest, are granted by international treaties, most notably by the Aarhus Convention (Weber and Weber 2009, 9).

Using this analogy, the authors suggest a “Memorandum of Understanding” between Internet governance bodies and civil society to ensure their equal participation in the existing governance model.

Other popular analogies include references to international trade law where self-regulation, good business practice and political lobbying have always played a major role in shaping global and local policies (Haufler 2013, 31 ff.).

Much like the greatly disputed lex Facebook, international companies, particularly within the baking sector, have long used their dominant position to influence policies and adapted to popular consumer demands even if there was no specific law requiring them to do so. Haufler refers to specific examples that include labour standards abroad, information privacy and environmental protection where the private sector takes the lead on policy making and leaves states to only later repeat those within local and international laws (Haufler 2013, 31).

Also, international food safety regulations, most notably the Codex Alimentarius and its implementing norms within the World Health Organization (WHO), are often referred to as a case of “private law making” (Henson and Humphrey 2011, 42).

As Henson and Humphrey note, these private standards have become a “prevalent part” of global food governance, relying on standards for food safety and quality developed by “private firms and standards setting coalitions, including companies and NGOs” (Henson and Humphrey 2011, 42). While developed by FAO and WHO, the document remains a classic example of soft-law and although non-binding to states, serves as a set of globally adopted fundamental safety standards among food suppliers.

These bottom-up processes of international standard setting and lawmaking have not gone unnoticed by international law scholars, who have coined the term “Global Administrative Law” (GAL) to frame them. While GAL remains disputed as to its methodology and application, it offers a comprehensive and insightful look at global governance.

The authors see global governance processes aligned along five categories, all based on “global administrative regulation”.

Kingsbury, Krisch, and Stewart include Internet governance with its multistakeholder model as one of those key types, referred to as “Hybrid Administration”. They view it as a “hybrid intergovernmental-private arrangement” and directly point to the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), discussed further herein, as a unique example (Kingsbury, Krisch and Stewart 2005, 15). Other four types include:

1) “International Administration” by formal international organizations, e.g. the United Nations Security Council;

2) “Network Administration” relying on “collective action by transnational networks of cooperative arrangements between national regulatory officials” with the work of and round the Basel Committee and the banking sector;

3) “Distributed Administration” of national regulators implementing international “treaty, network, or other cooperative regimes”; and

4) “Private Administration” done by private bodies, such as the International Standardization Organization (ISO).

Once the U.S. National Science Foundation, shepherd of the US academic network, allowed for its commercial use in the early 1990s, the commercial potential and rapid economic growth of online market stunned the White House officials. They attempted to resist the lobbying from both: local business and international governments, opting for a novel, non-commercial model of supervising critical technical resources of the network.

A new, unique solution was offered in 1998 with the setting up of ICANN – a non-profit corporation operating from California. As per ICANN Bylaws, its mission is to “ensure the stable and secure operation of the Internet’s unique identifier systems” (ICANN 2018, online).

In particular, ICANN:

1) coordinates the allocation and assignment of names in the root zone of the Domain Name System (“DNS”) and coordinates the development and implementation of policies concerning the registration of second-level domain names in generic top-level domains (“gTLDs”);

2) facilitates the coordination of the operation and evolution of the DNS root name server system; as well as

3) coordinates the allocation and assignment at the top-most level of Internet Protocol numbers and Autonomous System numbers (ICANN 2018, online).

ICANN offers “registration services and open access for global number registries”, working closely with the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) and Regional Internet Registries (RIRs) (ICANN 2018, online).

Its Bylaws explicitly state that “ICANN shall not act outside its Mission”, as defined above, and in particular it is not to “regulate (i.e., impose rules and restrictions on) services that use the Internet’s unique identifiers or the content that such services carry or provide”. It is characterized as holding no “governmentally authorized regulatory authority”.

Yet, despite this, in the last 20 years, the corporation has become the stage for all Internet governance-related debates and policy making. Although its primary legal obligation is towards its “contracted parties”, operating through lengthy private contracts with registrars, its policies and guidelines have long become actual policy standards within the Internet governance environment.

ICANN is considered the living example of multistakeholder governance, with issues discussed ranging from intellectual property to human rights, in particular privacy and freedom of expression.

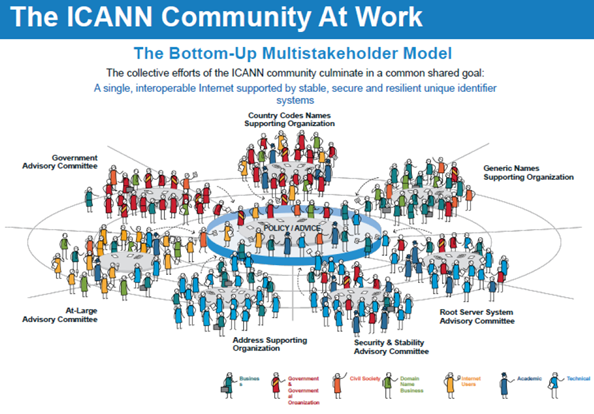

ICANN’s policy making is defined within its Bylaws. They reiterate ICANN’s “Core Values” – what could be considered basic principles of multistakeholder policy making. They include a commitment to preserving “the operational stability, reliability, security, global interoperability, resilience, and openness of the DNS and the Internet” as well as the “maintenance of a single, interoperable Internet”.

In doing so, ICANN relies on “open, transparent and bottom-up, multistakeholder policy development processes that are led by the private sector (including business stakeholders, civil society, the technical community, academia, and end users), while duly taking into account the public policy advice of governments and public authorities”. ICANN’s Core Values provide more insight into how the multistakeholder process works in practice.

The corporation and the community around it are to “seek input from the public, for whose benefit ICANN in all events shall act; promote well-informed decisions based on expert advice, and (C) ensure that those entities most affected can assist in the policy development process” (ICANN 2018, online). Multistakeholderism also implies “consistent, neutral, objective and fair” decision making based on “documented policies”.

All ICANN processes must remain non-discriminatory, make no “unjustified prejudicial distinction between or among different parties” with ICANN remaining “accountable to the Internet community through mechanisms defined in its Bylaws” (ICANN 2018, online). ICANN principles reflect the way the Internet works and have been purposely formulated in a flexible manner, serving more as guidelines than strict norms.

Effectively, their appropriate application depends directly on the nature of the situation in which they are to be used.

Yet, this complex, wide-spanning and vague formula makes ICANN a unique policy battle ground, often criticized for being subject to opaque lobbying efforts from the domain name and IT businesses (Froomkin 2003). What adds to that argument is the significant economic power the California-based non-profit holds, with funds under management as per June 30, 2018, amounting to 443 million USD (ICANN 2017, online).

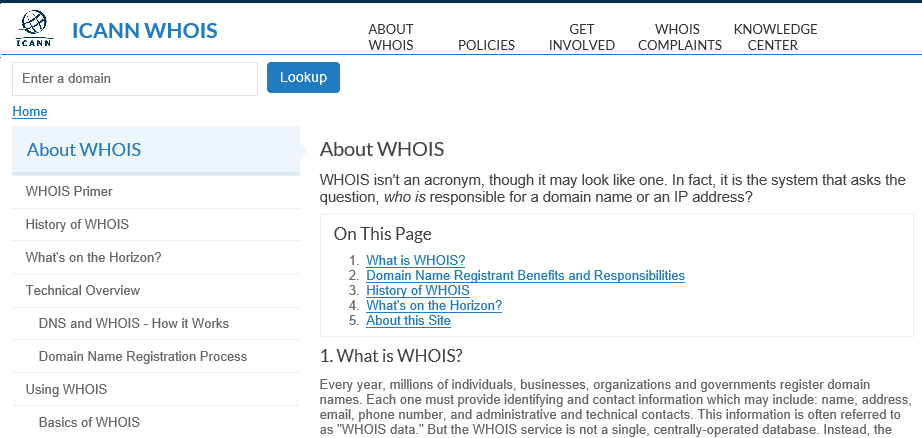

Since its creation in 1998, ICANN has struggled with implementing European standards of privacy protection in particular due to its original design comprising a WHOIS database – a data resource containing information on all domain name registrants, operated by ICANN contracted parties: DNS registries and registrars. ICANN obliged all contracted parties to hold, update and make publicly accessible data on all domain name holders.

This resource has been used as a primary reference for various categories of Internet users: customers considering a purchase from an online store, communities compiling lists for anti-spam filters, law enforcement, cybersecurity professionals as well as IP lawyers aiding companies in protecting their intellectual property threatened by the rapid evolution of online communications.

The crucial problem with the WHOIS has always been that it directly violated all European data protection laws. Long before the GDPR revolutionized international online contracting, European Union’s data protection standards ensured data subjects that their data can only be collected and kept if there is a legitimate ground to do so, either imposed by law or a contract, and particular conditions are met (explicit consent from data subject, data necessity, accuracy and minimalization).

Not all data collected by registries and registrars were necessary for the performance of the domain name contract – their scope was far broader than needed.

Yet, ICANN contracted parties were obliged, under pain of financial consequences for a breach of the ICANN contract, to collect data on persons or businesses who registered a domain name, including their name, address, e-mail, phone number and administrative contact – what amounted to a WHOIS record. The registrar or registry of the domain was obliged to maintain a publicly accessible WHOIS database with these records (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Archived ICANN website on WHOIS

This practice has met with long-standing opposition from civil society and European data protection ombudsman, including the Article 29 Working Party (WP29), including letters of December 2017 and of April 2018 (WP29 2017, 2018). This was for two primary reasons: the broad array of data was collected and made public without a valid aim and left data subject with no possibility to have their data removed.

Moreover, the data has been subject to commercial enterprise, with companies like MarkMonitor or Domain Tools monetizing the data for the sake of brand protection companies. While brand protection and the pursuit of trademark infringers is a legitimate aim as per GDPR, the automated collection and distribution of data has always been far beyond what is considered due process and privacy law in the EU.

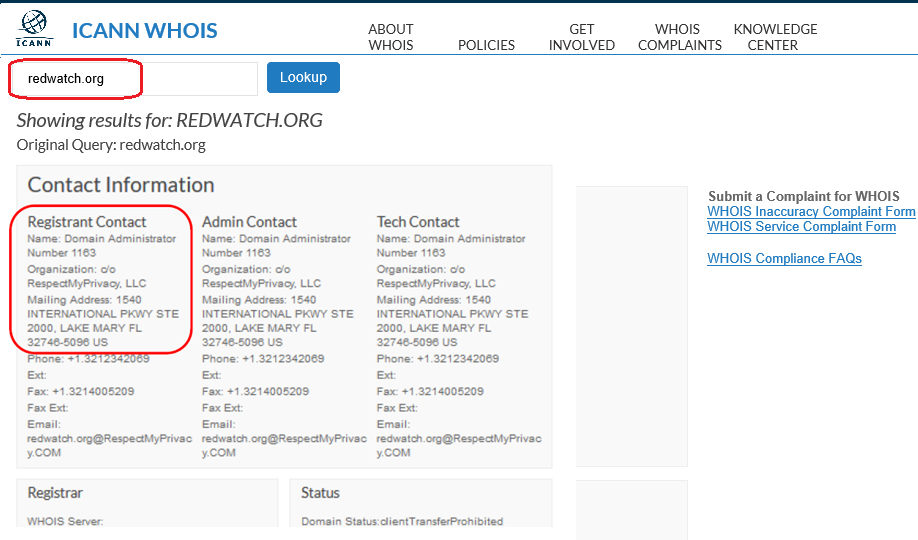

The second argument against WHOIS has been the inaccuracy of WHOIS data – the market gave rise to a vivid enterprise of privacy proxies: companies offering commercial services to those willing to keep their trademark owner details secret (see Figure 2). This practice largely deemed futile all law enforcement efforts to identify online law infringers.

On the other hand however, those who could not afford the services of privacy proxy were forced to have their data revealed, accessible to potential spammers or, more significantly, to law enforcement authorities of non-democratic regimes, e.g. a LGBT website owner in Russia who would not use a privacy proxy could be easily identified by local police, surrendering them to national laws setting specific limits on freedom of expression.

Figure 2: Archived WHOIS record with data of a privacy proxy

WP29 expected ICANN “to develop and implement a WHOIS model which will enable legitimate uses by relevant stakeholders, such as law enforcement, of personal data concerning registrants in compliance with the GDPR, without leading to an unlimited publication of those data”. The core of the issue is however that ICANN operates on a bottom-up, multistakeholder model of governance (see Figure 3).

The California-based ICANN staff cannot impose policy onto the global community of stakeholders – states, users and businesses have to develop it themselves in a complex, bottom-up process (for a detailed record of policy development processes visit: https://www.icann.org/policy).

Figure 3: ICANN multistakeholder policy making model

Following the dawning of the GDPR, ICANN (the California-based company) decided to disable the global resource of personal data, much to the dismay of law enforcement and IP law companies: as of May 2018, WHOIS went dark. This was done through a “Temporary Specification” – an interim measure aimed at safeguarding all ICANN contracted parties against possible GDPR liabilities, imposed (temporarily) by the California-based ICANN staff.

This does not mean however that a domain name registration no longer carries an obligation to provide registrant’s data – quite the opposite. The current challenge for the ICANN community is to find a reasonable solution for processing registrants’ data for all legitimate aims and this is to be done through the multistakeholder, bottom-up process, as opposed to top-down law enforcement by states, like the GDPR itself.

Effectively, the results of the Expedited Policy Development Process (EPDP), as published in the draft report of Nov. 21, 2018, are the initial result of a bottom-up, international norm setting with a strong cybersecurity impact (EPDP 2018).

Law enforcement worldwide will have to make use of what the global, multistakeholder community deems the appropriate balance between privacy and security, due process and legitimate aims. States hold equal footing with business, academia and internet users in defining what this balance is.

Implications and Lessons for the Future

When discussing governance and its evolution, Jessop argues new models of governance built upon the failures of old ones, describing the process as “second order governance” (Jessop 2015, 170). This process brings with it a reordering of the networks and improvement of communication modes, rooted in institutional changes.

While his argument is focused on states, the general lessons on governance seem to be applicable also to cyberspace with its multistakeholder model. The post-World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS) decade (2005-2015) fueled discussions on specifying the ambiguous notion of “Internet governance”, most significantly through defining the “respective roles” of states, business and civil society.

While governments eagerly discuss Internet governance, the current IG landscape was originally designed as the effect of bottom-up governance models, rooted strongly in the technical community, just to mention the Internet Society (ISOC) or the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) with its “Requests for Comments” (RfCs), community-developed common standards voluntarily followed by its members: Internet service providers or software developers.

While “security by design” remains a common paradigm within both: ISOC and IETF, there is no connection to be made between this extra-legal, community-based rule making approach and the hard norm setting model of, e.g. NATO (Rescorla 2003).

While ICANN, ISOC, and the IGF have been attending to the issue, this communications gap holds crucial relevance for the development of any effective international cybersecurity policies and must be addressed by whatever model of global cybersecurity will be developed.

There can be no effective cybersecurity policy developed solely at a governmental level, without a strong presence of the technical community and vigilant input from civil society.

The article was originally published in The Visio Journal 3 (2018)

References

ARTICLE 29 Data Protection Working Party. 2017. Letter of December 11, 2017 to Dr. Cherine Chalaby and Mr. Göran Marby, Chairman and President and CEO of the Board of Directors. https://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/just/document.cfm?doc_id=48839.

———. 2018. Letter of April 11, 2018 to Mr. Göran Marby, President and CEO of the Board of Directors.

Bygrave, Lee A. 2005. Internet Governance by Contract. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Clark, David D. 1992. A Cloudy Crystal Ball – Visions of the Future. https://groups.csail.mit.edu/ana/People/DDC/future_ietf_92.pdf.

Drake, Willian J. 2009. “Introduction: The Distributed Architecture of Network Global Governance.” In Governing Global Electronic Networks, edited by William J. Drake and Ermest J. Wilson, 8-9. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Dutton, William H. 2012. “The Fifth Estate.” In The Oxford Handbook of Governance, edited by David Levi-Faur. Oxford: OUP.

Expedited Policy Development Process (EPDP). 2018. Initial Report of the Expedited Policy Development Process (EPDP) on the Temporary Specification for gTLD Registration Data Team. https://www.icann.org/news/announcement-2-2018-11-21-en.

Froomkin, A. Michael. 2003. “: Toward a Critical Theory of Cyberspace.” Harvard Law Review 116 (3): 749-873.

Haufler, Virginia. 2013. A Public Role for the Private Sector: Industry Self-Regulation in a Global Economy. Washington DC: Carnegie Endowment.

Henson, Spencer, and John Humphrey. 2001. “Codex Alimentarius and private standards.” In Private Food Law: Governing Food Chains Through Contracts Law, Self-regulation, Private Standards, Audits and Certification Schemes, edited by Bernd M. J. van der Meulen, 149-174. Wageningen, The Netherlands: Wageningen Academic Publications.

Huizer, Erik, and David Crocker. 1994. IETF Working Group Guidelines and Procedures. RFC 1603.

ICANN. 2017. Budget plan for 2018. https://www.icann.org/en/system/files/files/adopted-opplan-budget-fy18-24jun17-en.pdf.

ICANN. 2018. Bylaws for Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers. https://www.icann.org/resources/pages/governance/bylaws-en/#article1.

Jessop, Bob. 2015. The State: Past, Present, Future. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Kingsbury, Benedict, Krisch, Nico, and Richard B. Stewart. 2005. „The Emergence of Global Administrative Law.” Law and Contemporary Problems 68 (3): 15-45.

Levi-Faur, David, ed. 2012. The Oxford Handbook of Governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

McNair, Corey. 2018. Worldwide Retail and Ecommerce Sales: eMarketer’s Updated Forecast and New Mcommerce Estimates for 2016-2021. eMarketer. https://www.emarketer.com/Report/Worldwide-Retail-Ecommerce-Sales-eMarketers-Updated-Forecast-New-Mcommerce-Estimates-20162021/2002182.

Rescorla, Eric, and Brian Korver. 2003. Guidelines for Writing RFC Text on Security Considerations, Request for Comments: 3552. https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc3552.

Weber, Rolf H., and Romana Weber. 2009. „Inclusion of the Civil Society in the Governance of the Internet. Can Lessons be drawn from the Environmental Law Framework?” Computer Law Review International 10 (1): 9-15.

World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS). 2005. Tunis Agenda for the Information Society. http://www.itu.int/wsis/docs2/tunis/off/6rev1.html.