This paper aims to explore the history, structure, and economic consequences of the currency board in Bulgaria, which was introduced as an emergency measure to combat the late-nineties economic crisis, though has stayed in place ever since.

The paper provides a brief description of the general theory of currency boards, followed by a detailed analysis of the various aspects of the economic crisis during the Videnov government, resulting from the return to centralized and state-led economic policies: high inflation, shrinking of household incomes and savings, deterioration of trust in the banking system, collapse of the baking system and national budget crisis.

Then, the paper explores the currency board introduced to remedy the crisis, as well as its consequences for the reshuffling of the institutional setting and the stabilization of Bulgaria’s economy, in terms of inflation, gross domestic product, investment, public debt and stability of the banking system. A comparison with similar instruments put in place in the Baltic countries and their role in those countries in the process of accession to the Eurozone is also provided.

Finally, it attempts to contribute to the current debate on whether the Bulgarian currency board should be scrapped, arguing that the trade-off between economic and fiscal stability and freedom of monetary policy has so far been well worth it and there is little need for reform at the current point given the country’s trajectory towards adopting the euro in the near future.

1. The Travails of Slovene Transitioning

Bulgaria is among the countries which have spent a relatively long period under a currency board arrangement – the fixed exchange rate regime has been in place since mid-1997. In the past few years, however, there have been voices advocating for its scraping claiming that the regime has served its purpose, but now has become a constraint on conducting independent monetary policy. Given the political trajectory of Bulgaria towards adopting the euro and the wide consensus that the board will stay in place until the country joins the euro area, the board will likely be removed in the following decade at the earliest.

This paper examines the economic realities before and after the introduction of the Bulgarian currency board. It also provides its consequences and importance for the economic development of the country in the past two decades, as well as compares its trajectory with other countries that have similar instruments and have since adopted the common European currency.

2. What is a Currency Board?

Though commonly used as an institution of monetary policy, we shall define the term “currency board”, if only to limit its meaning and use in this case. In this paper, a currency board means both the regime of maintaining a fixed exchange rate with a foreign currency and certain coverage of money supply with foreign reserves, and the authority in charge of enforcing this policy. As this paper is concerned primarily with the effects and consequences of the policy, unless specified, “currency board” refers to the exchange rate regime.

In a nutshell, under a currency board, a country’s government and central bank give up their power to control the price and supply of currency, and thus commit to maintaining an exchange rate peg to a foreign currency. The latter is most often one that is considered to be stable, one of the most desired reserve currencies, these usually being the U.S. dollar or the euro.

In consequence, the central bank gives up its ability to mint new currency, unless it has sufficient reserve of the one that it is pegged to. Such a regime is usually applied when a country wishes to put an end to a period of economic instability, especially as a measure to rein in galloping inflation and provide an external signal that it intends to keep a sound and strong monetary policy (a rather exhaustive compilation of studies on currency boards is available in Gross et al. 2012).

3. The state of the Bulgarian economy before the introduction of the currency board

One could say that adopting a currency board was hardly a choice for the caretaker government that temporarily took power after the resignation of prime minister Videnov and before the organizing of the next election, led by Stefan Sofiyanski and put in power in the winter of 1997.

At that time, the political landscape of the country was changing dramatically. Public support was shifting from the Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP) to the Union of Democratic Forces (UDF), as a result of a significant economic downturn during the Videnov government. In the 1995-97 period, the socialist government had all but halted the economic transition towards a market economy and attempted to reverse the trajectory of the reforms toward a softer central planning via a so-called “socially oriented economic policy” (Kalinova 2006, 291–8).

In 1996 the share of government-controlled prices surpassed just over half of the products, leading to major imbalances between the supply and demand of products. This, combined with the failures of mass privatization, foiled by the concentration of privatization bonds in unstable or outright criminal privatization funds, the “draining” of state-owned enterprises and a sharp drop in trust in the banking system set the stage for economic collapse.

Reviewing the key macroeconomic indicators for the period before and during the socialist government reveals the severity of the economic conditions. Probably the most telling indicator for the real-world dimension of the economic crisis is inflation, as measured by the consumer prices index.

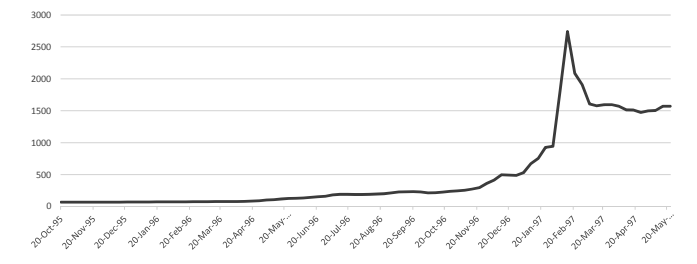

According to the World Bank data (preferred here as the data series published by the Bulgarian National Statistical Institute, NSI, do not allow for comparisons with the period before the economic crisis as they do not cover the entire democratic history of the country), the annual inflation in Bulgaria rose from 62% in 1995 to 1058% in 1997, which was considered uncontrollable by the experts and government alike (See Figure 1).

To make things worse, in year 1997 the highest inflation rate was recorded in the cost of the food basket (1094% according to NSI data, including the most commonly used food groups such as meat, vegetables, fruit, oils, bread), the highest being inflation rate in price of meat (1411%) and price of vegetables (1444%), thus affecting the basic capability of many to sustain themselves and their families.

Figure 1: Annual Change in HICP inflation (%), Bulgaria, 1989-1997

Source: World Bank, http://www.worldbank.org/.

Source: World Bank, http://www.worldbank.org/.

At the same time, there was a significant decline in GDP per capita, as it slid from 1554 USD in year 1995 to 1345 in year 1997. The effect of this extreme decline is evident in the sharp drop in household final consumption expenditure, from 74% of GDP in year 1994 to 58% in year 1998. Evidently, the crisis significantly reduced the ability of households to spend. The rapid rise of inflation also meant that household savings were losing their value at an alarming rate.

Meanwhile, public finances were not doing well either. In year 1997, the debt of the national government reached almost a 100% of GDP, and GDP itself was declining rapidly, especially in the first quarters of the year. Foreign trade also experienced a setback, declining by about 15% in a single year.

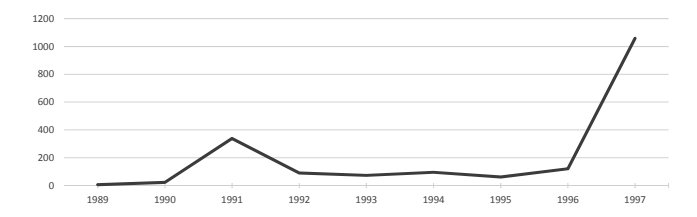

Furthermore, central bank reserves were being depleted in an unsuccessful attempt to support the exchange rate of the Bulgarian lev. The banking system was failing, as the devaluation of deposits and sharp drop in trust, resulting in almost a third of the banks going under in the years of the crisis (See Figure 2) (Nenovsky and Rizopoulos 2003, 909).

Figure 2: Devaluation of the Lev (BGN to USD Exchange Rate), 1995-1997

The economic failure coincided with political upheaval in the winter of 1996, and the introduction of extraordinary measures for economic stabilization, together with the reversal of many of the Videnov government’s disastrous economic policies. Thus, the currency board was introduced.

4. The Conditions of the Bulgarian Currency Board

The late-nineties economic crisis is not the first time that an introduction of a currency board was considered in Bulgaria. Similar mechanisms, aiming at reducing the risk of inflation and economic instability, were proposed right after the transition to democracy and market capitalism. This was done in the so-called Rahn-Utt Plan for the transition, and also voiced by Steve Hanke and Kurt Schuler (Hanke and Shuler, 1991). At that time, however, both the newly-former democratic forces and the socialist opposition deemed a currency board to be too harsh and constraining measure, which is why they opposed its introduction.

While the currency board introduced in the summer of 1997 shares most of the characteristics of both the typical arrangements and the early-nineties proposals, it has some unique characteristics. Below are the features of the currency board in Bulgaria, broadly following the description provided by Chobanov and Angelov (2003, 51-2). The currency board:

- has an obligation to buy and sell the foreign reserve currency without restriction;

- maintains a currency reserve to cover for the local currency in circulation, and issues local currency only if it can be covered by the reserve;

- extends no loans to the government;

- does not conduct monetary policy;

- invests in low-risk assets denominated in its reserve currency; and

- in practice, redirects the monetary policy to the reserve currency country.

- These features follow the standard currency board formula. The Bulgarian version of it has several distinctive characteristics:

- the Bulgarian national bank may hold deposits by state institutions on the liabilities side of the balance sheet of the currency board. This ensures a higher than 100% coverage of the monetary base with foreign reserves;

- mandatory minimum reserves of commercial banks; and

- in cases of systematic risk for the banking system the Bulgarian national bank may act as a lender of the last resort.

With these features, the Bulgarian currency board qualifies as a second-generation or a quasi-currency board, where some of the traditional central bank functions are maintained, together with the restraining mechanisms.

Originally, when the currency board was introduced, the reserve currency was the German mark, as it was viewed to be among the most stable currencies of the countries that were about to introduce the euro, at a 1:1 exchange rate. The U.S. dollar or a basket of reserve currencies were also considered, but the political goal of the country to become an EU member in the future and the geographical proximity of the common market weighed on the decision to peg the currency only to the mark. After the adoption of the euro by the original 11 members of the Eurozone, as the German mark was no longer in use the Bulgarian lev became pegged to the common currency at the same exchange rate as the German mark – at 1.96:1. This rate has been held constant ever since.

5. The Immediate Consequences of the Currency Board

The first and most obvious consequence of the introduction of the currency board was the institutional reshuffling, new powers, and limitations to the legal capabilities of various government bodies. As Nenovsky and Rizopoulos (2003, 915-23) demonstrate, the board completely restructured the dynamics of the relations between the main players concerned with Bulgarian monetary affairs: on one hand, the foreign creditors of the country, most notably the International Monetary Fund, the government and the central bank, commercial banks, private companies and households as creditors; and on the other hand, state-owned, subsidized or crony banks and businesses as debtors.

According to Nenovsky and Rizopoulos (Ibid., 925-6), the new monetary regime shifted (in the broadest sense) the institutional structure in favour of the interests of private companies and commercial banks, to the detriment of crony structures and at the expense of the decision-making power of the government and the central bank. From a political perspective, at the peak of the crisis, а broad consensus existed in favour of the introduction of the currency board, but later it was repackaged as a part of the debate for the general political and economic trajectory of the country, with euro-optimist forces supporting the maintenance of the board and euro-sceptic ones opposing it.

That said, the most important consequences of the profound institutional change are the macroeconomic stability and economic policy predictability in Bulgaria. Generally, it is pretty hard to predict the impact of any policy (and the currency board in particular), but the currency board is one of the few policy examples where there can be no debate about its vastly beneficial effect on the economy and economic policy (see, inter alia, Nenovsky and Hristov, 2002, 70-1).

Probably the most important consequence of its introduction was the almost immediate reining in of the inflation and its reduction to trivial levels, indicative of healthy economic development. Compared to the 1058% inflation in 1997, 1998 had a 18.7% increase in the prices of items included in the consumer basket, which was not low, but still the lowest since the begging of the economic transition. In the following decade, inflation in the country averaged 6.4%, which was significantly higher than in most Western European countries, but in no way indicative of economic instability. Rather, those inflation rates were an artefact of the rapid economic catch-up development during the period of Bulgaria’s accession to the EU and prior to the crisis.

The same trend is mirrored in the growth of the country’s gross domestic product – while the first years of transition were characterized by overall economic decline, the decade before the 2008 economic crisis are ones of rather rapid growth, averaging 4.6% per annum (5.8%, should we exclude the decline in 1999).

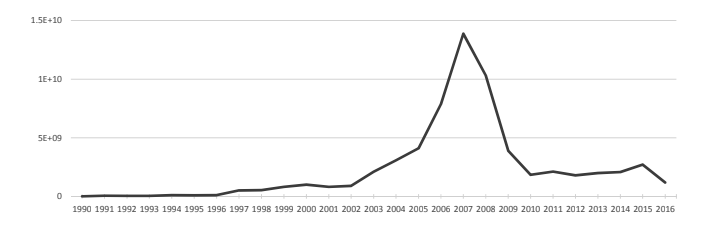

A key indicator of economic stability is investment. Companies rarely direct funds to countries with unstable economic environment and unpredictable economic policies. Unlike the previous two indicators, foreign direct investment (FDI) did not decline during the late 1990s’ economic crisis, mostly because it was very low to begin with. Net FDI inflows started picking up only a few years after the introduction of the currency board, reaching a total of 13.9 billion USD in 2007, up from 500 million in 1997 (See Figure 3). While FDI took a major hit from the 2008-09 crisis, its dynamics in the past two decades clearly demonstrate clearly that the currency board is a more than appropriate tool for signaling stability and predictability to investors. Being pegged to the euro also resulted in a significant stabilization of the exchange rate of Bulgarian lev towards third currencies, as in practice it adopted the exchange rate of the euro. While in 1997 the rate reached heights of more than 2000 leva for a dollar, in the following decade it fluctuated around 1.5.

Figure 3: FDI Net Inflow, Bulgaria, 1990-2016

Source: World Bank, http://www.worldbank.org/.

Source: World Bank, http://www.worldbank.org/.

The key statistics of the central government are also favourable of the board. While government debt had reached an all-time high of 97% of GDP in 1997, it has since been declining, all the way to 13% of GDP in 2008. Overall, thanks to prudent economic policy, Bulgaria has been among the EU countries with the lowest debt-to-GDP ratio. Budgetary performance in terms of deficit has been more mixed.

Despite that, deficit levels as low as 1996’s 9.9% were never experienced again, and before the onset of the 2008 crisis the mean balance for the decade stood at 0.7% surplus, allowing for some savings and filling of the fiscal reserve. With the data available by the Ministry of Finance only starts from 2003, at the end of that year the fiscal reserve stood at 3,85 million leva and reached 8,4 billion leva (or 9% of GDP) just five years later at the end of year 2008. This sum allowed for significant cushioning of the inevitable hit that government spending took during the economic crisis.

Since the banking system and household deposits were among those experiencing the worst hit in the crisis of the late 1990s, it is well worth investigating how they fared after the introduction of the currency board. There were no failures of banks after 1997 until the Corporate Commercial Bank bankruptcy in 2014. It could be argued that this case was due to specific reasons (Ponzy-type of operation of the bank, close links to government, failure of supervision, etc.) rather than economic instability (Ganev 2017, p. 3-5).

The trust in the banking system returned after the run on banks in the 1995-96 period, which, together with the rapid growth of household income, led to significant increases in the total volume of deposits. According to central bank data, they grew by about 30% annually in the pre-crisis period. Afterwards, the growth of deposits continued, albeit at a slower rate.

6. Currency Board and the Adoption of the Euro

The broad political consensus in Bulgaria (along with the EU member-state obligations – all members are expected to adopt the common currency at some point after their accession, unless they explicitly opt out, which Bulgaria has not done) is that the country will adopt the euro as its currency at some point in the future and consequently abandon the currency board in favour of monetary policy of the European Central Bank. Yet, only a few concrete steps have been taken in this direction. It is likely that the trajectory that the Bulgarian monetary institutional setting will take during this upcoming process of euro adoption will be like the ones in the several other Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) countries with similar currency boards which have already become part of the common currency area, such as Estonia and Latvia.

Discussing the role of the Estonian currency board in the process of adopting the euro, Kattai (2004, 202) demonstrates that the currency board is instrumental in maintaining low inflation rate and as such meeting the Maastricht criteria (they include maintaining low inflation, among other things such as low deficit, manageable debt and low interest rates), which is a condition for the entrance in the ERM-2 and the consequent adoption of the euro. Kattai’s counterfactual models also demonstrate that modelled future inflation is the lowest under a currency board as compared with other monetary policy instruments. His findings are broadly corroborated by De Haan et al. (2001), who examine the currency board structures in the Baltic countries and compare the Estonian euro-pegged currency board and the Lithuanian one, which pegged the currency to the dollar.

They find (Ibid., 238-40) that the Estonian choice turned out to the superior one in terms of meeting the macroeconomic and monetary goals of the two countries, primarily because of the pegging of the national currency to that of a country with a more similar economic cycle and closer levels of economic development. A final argument is provided by Gulde-Wolf and Keller (2002), who point out that at the time of the adoption of the currency boards in the CEE, the ERM-2 did not accept countries with currencies pegged to reserve currencies other than the euro, which in turn made it the default choice for those on track of eventually joining the European monetary union.

The following success of all the Baltic countries in adopting the euro confirms the expectations of earlier researchers that their currency boards lead to sufficient macroeconomic stability. This in turn means that there is little motivation for Bulgaria to abandon its currency board before adopting the euro. Based on previous experience it can only serve as an additional assurance that the country will meet its obligations. Given that Bulgaria has met all the formal criteria, it is primarily a matter of political will—both from the European commission and the Bulgarian government—to start the formal process of the Bulgarian accession to the Eurozone.

7. Key Takeaways and Policy Lessons

It is rather curious that in recent years a discussion on the dismantling of the currency board has remerged in Bulgaria. This discussion is interestingly led by the former Prime Minister Ivan Kostov whose government finalized its introduction twenty years ago. The arguments presented in this paper, however, show little need for that. On the contrary, surrendering monetary discretion has done little to hamper the economic development of Bulgaria. All the data and evidence provided above demonstrate that the currency board has been instrumental in the stabilization, recovery, and growth of Bulgaria during its decades of economic transitions.

Here we have demonstrated that currency boards are an effective tool for combating economic crises and therefore should always be taken into consideration as an option for reining in inflation that is spiraling out of control and stopping major economic downturns. A comparison with different setups of the Baltic countries shows that this solution is far from a silver bullet and needs to be designed so that it reflects the needs and current conditions of the economy in question.

Furthermore, currency boards come handy in the process of accession to the Eurozone, both as a tool for maintaining the required stability and a signal for the candidate country’s commitment to sound money and predictable and reliable economic policy.

The paper was originally published in the Visio Journal No. 2.

References

De Haan, Jakob, Helge Berger, and Erik Van Fraassen. 2001. “How to reduce inflation: An independent central bank or a currency board? The experience of the Baltic countries,” Emerging markets review 2, no. 3: 218-43.

Ganev, Petar. 2017. Democratic Backsliding in Bulgaria. Sofia: Institute for Market Economics.

Gross, Thomas, Heft, Joshua, and Douglas Rodgers. 2012. “On Currency Boards–An Updated Bibliography of Scholarly Writings,” Studies in Applied Economics 1 (June): 1-82.

Gulde-Wolf, Anne-Marie, and Peter Keller. 2002. “Another Look at Currency Board Arrangements and Hard Exchange Rate Pegs for Advanced EU Accession Countries”, in Alternative Monetary Regimes in Entry to EMU. Tallinn: Eestipank.

Hanke, Steve H., and Kurt Schuler. 1991. Currency Boards for Eastern Europe. The Heritage Lectures No. 355. Washington, D. C.: The Heritage Foundation.

Kalinova, Evgenia. 2006. The Bulgarian Transitions 1939-2005. Sofia: Paradigma.

Kattai, Rasmus. 2004. “Analyzing the Suitability of the Currency Board Arrangement for Estonia’s Accession to the EMU,” Modelling the Economies of the Baltic Sea Region 17: 167-206.

Nenovsky, Nikolay, and Kalin Hristov. 2002. “The new currency boards and discretion: empirical evidence from Bulgari,a” Economic Systems 26: 55–72.

Nenovsky, Nikolay, and Yorgos Rizopoulos. 2003. “Extreme monetary regime change: evidence from currency board introduction in Bulgaria,” Journal of Economic Issues 37, no. 4: 909-41.

Stanchev, Krassen. 2004. “Political attitudes and currency board,” in Anatomy of transition, pp. 56-61. Sofia: Ciela.