Global markets cannot ignore the impact of losing agricultural supply from Ukraine and Russia, and European agricultural authorities are well aware of the risk. Although it is unlikely that Germany will experience shortages of wheat and other essential grains, the rising prices of agricultural products worldwide will have an impact.

As both Russia and Ukraine are leading exporters of agricultural products, Russia’s invasion of its neighbouring country is forcing global flows of such products to adjust. Supply from Russia has dried up, partly because of sanctions, partly because Russia imposed a ban on grain exports to the world market. While Russia stopped exports of grains such as wheat, barley and rye, Western sanctions are preventing Russia from exporting fertiliser and inhibit the bilateral trade with other agricultural products.

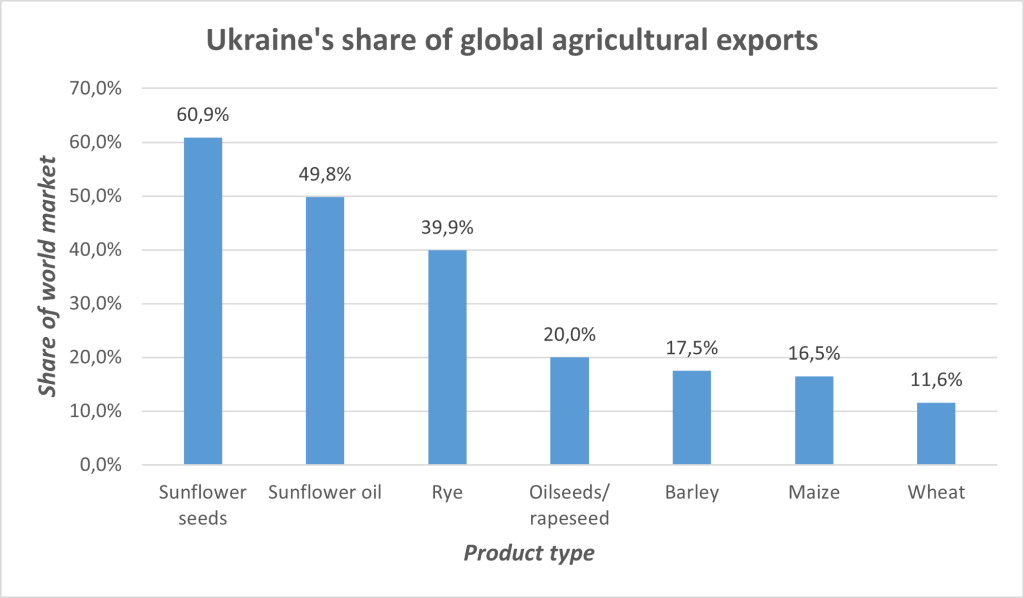

Ukraine, on the other hand, has been severely affected by the war and the destruction of its infrastructure. Shortages of seed, fertiliser and fuel are imposing further constraints on production. As a result, Ukraine is unlikely to maintain its usual levels of exports.

Added to that, Russia’s invasion – in violation of international law – has created a massive movement of refugees, while all men of military age in Ukraine have been mobilised to defend the country. As a result, there is a severe shortage of agricultural manpower. With planting season soon coming to an end, it means that granaries are unlikely to be refilled in late summer.

Cumulatively, therefore, agricultural exports from Ukraine and Russia are likely to be far lower than usual, both this year and next. This will reduce supply on global markets. Nonetheless, Europe’s supplies of essential foodstuffs are secure. For example, when it comes to wheat and barley, the EU is largely self-sufficient.

However, a different situation presents itself when it comes to maize. European livestock farmers rely on it for animal feed, which was often imported from Ukraine and Russia. A significant share of fodder maize, for instance, was procured from Ukraine – about 20 percent of the required volume. The loss of these imports led to all-time highs on European agricultural exchanges at the start of the invasion.

The increase in feed costs will drive up the prices of animal products. Consumers are already beginning to feel the pinch. There is some uncertainty, however, about how trade flows between the EU and Ukraine, including of agricultural products, will evolve. But it is evident that European agricultural authorities and enterprises will have to respond to new challenges in a rapidly evolving environment.

Some policy responses are already in motion. For instance, European authorities are for the first time discussing deploying the crisis reserve. This would provide the member states with an additional budget of €472m to support farmers. The purpose of this reserve is to provide European farmers with additional support in times of crisis, for instance during a drought or similar emergency.

The fund is fed from reserves created as part of the previous year’s agricultural budget and therefore does not create an additional burden on the planning status of the European agricultural budget. Authorities are proposing to use the additional funds to dampen the effect of the price increases of feed, fertiliser and fuel. Furthermore, the EU wants to allow the member states to provide certain forms of extraordinary financial support to their farmers.

At the same time, the new situation provides an incentive to fundamentally modernise the agricultural sector. Technologies such as drone-based fertilising, advanced seed and automated machinery could make European agriculture more efficient in future. This will be necessary in any case to help feed the world’s growing population while responding to climate change.

Future harvests could thus potentially be larger and help mitigate supply bottlenecks in other parts of the world. It is to be hoped that the additional funds will be used – at least in part – for investments in such future-oriented technologies.

At the same time, the Commission is considering supporting Ukrainian farmers with diesel and seed. Perhaps this would make it possible for the most urgent work on the farms to be done, which would create an opportunity to gather a harvest in summer – but whether such supplies would be sufficient considering the limited time left for planting is unclear.

In the EU member states, it is likely that arable land purposefully left fallow will be released to be put back into production. How exactly this will be done is unclear at this stage. But it is conceivable that such areas – intended as ecological priority land – will be granted permission to be used to grow feed and protein plants. Through these measures, the Commission hopes to mitigate the anticipated shortages of animal feed.

Essentially, these areas were explicitly removed from production to combat species extinction in the European cultural landscape. Putting them back into use risks extending the decline of biodiversity in Europe. But still: it is essential to maintain Europe’s food security – and supply third countries, if possible.

While European food markets are largely self-sufficient and sovereign, the same is not true of many countries in the Global South. Some North African and Asian nations, historically large buyers of Ukrainian agricultural produce, are now at risk of acute food shortages. The people of Ukraine face the same risk. This means that global solidarity is a moral imperative.

Written by Maximilian Reinhardt, Policy Advisor on economy and sustainability