Last days the European Union leaders discussed potential sanctions to deter cyberattacks. However, they did not provide any details. The European Union is not the first political organization which engages in debate on such a topic. Others like the United Kingdom and particularly the United States have used a variety of means to deter cyberattacks and punish the assailants.

The paper aims to present the potential tools, which the EU could use to deter cyberaggression and later analyze the potential consequences of using them. What is more, the obstacles organization could meet will be presented and finally the evaluation of the effectiveness of these measures and the probability of using them. This analysis will be done to answer the central question: how to create a system of punishing for a cyberattack. The analysis will be done basing on the experience of other countries, especially the case of the United States. However, the situation with the EU looks different, because it is a political organization, which consists of 28 members.

Introduction

The growing number of cyberattacks have become a serious security challenge for individuals, enterprises and states in the European Union (Fruhlinger 2018). Increasingly, they are used as a weapon, which is aimed at disrupting critical infrastructure, paralyzing weapon systems, destabilizing the political situation, interfering in the election process, altering significant voting, etc. States such as China, Russia, Iran and North Korea more and more often have used cyberspace as a new arena of conducting a hostile activity. Among the victims were the EU countries such as Germany, the Netherlands or Great Britain but also the EU institutions. In response to this growing threat, the bloc of countries led by the Netherlands and Great Britain proposed to extend sanctions regime to include cyber-attacks (Drozdiak and Chrysoloras 2018). Despite the protests from the Italian government, the EU leaders supported this idea (de Carbonnel and Emmot 2018).

Analysis

Developing an effective system of sanctions against cyberattacks is a daunting challenge for every political actor including the EU. There are several obstacles which need to be addressed like attributing attacks to a certain assailant, the communication policy of presenting proofs about the source of the attack or influencing member states of the EU to impose sanctions. However, the EU may use examples of the other countries, which have already used some sanctions against the attackers.

The Problem of Attribution

One of the main problems to retaliate effectively against the authors of cyberattacks is attribution. The architects of global network did not think about security issue when they projected the Internet. Initially, it was created as the tool to establish communication between the military commands in the United States and later also to facilitate the exchange of information between the American academic entities. No one at that time was planning global expansion. Construction’s flaws lead to the situation that the cyberspace has become the oasis for the illegal activity (Kaplan 2016, 10-21). Initial cases of hostile activity were dominated by the young teenager’s desire to earn extra money.

However, at the beginning of the 21st century more and more advanced, long-time incidents took place and countries, particularly the United States started to treat cyberattacks as the severe threat for national security. Several countries, especially Russia and China were accused of standing behind the attacks, which both of them vehemently denied. Unfortunately, the problem of the identification of the assailant has seemed unresolved until today, mainly due to the architecture of the cyberspace. We are able to trace the IP addresses, which identify the computer in the virtual world, but manipulating them is an extremely simple and available even for beginners. That is a reason that the attack conducted against the members of the European Union from Chinese addresses did not mean that it was orchestrated by Chinese but maybe is the work of Russians or Israelis hackers using the IP located in China.

Despite the difficulty, the American private company Mandiant in 2013 collected data and published reports accusing the Chinese military united 61390 located in Shanghai of conducting a bunch of cyber espionage campaigns against the US. The proofs were solid. It was the first time in history when someone delivered a very detailed and rich report on attacking techniques and tools. It is worth also mentioning how hackers were identified. American IT security experts under the leadership of Mandian Company used the exploit in Chinese hackers’ security networks and got access to their systems collecting logs and tracking every move than creating the digital diary. What is even more interesting, it was purely private initiative without the government engagement. However, the Mandiant report was just the beginning (Mandiant 2013). Since that time the United States identified the source of cyberattacks accusing Russia of interfering in the presidential election and breaching the Democratic Committee in 2016. Not only was Russia identified as the source of attack but also China, Iran and North Korea. Unfortunately, in some cases, the American institutions have not always provided persuasive material to support their accusation (Goldsmith 2017).

The EU members have also possessed capabilities to attribute cyberattacks. The Dutch intelligence conducted an effective operation against Russian intelligence assets engaged in hacking United States presidential election. What is more, the United Kingdom accused North Korea of paralyzing own healthcare system with the use of WannaCry ransomware. Germany was able to identify Russian traces in hacking Bundestag and France detected the Russian false flag operation against Le Monde station. These examples showing the increasing number of technical attributions of the attacks and that the EU members have possessed these capabilities. Likewise, in Skripal case certain countries could share intelligence information with others and in this way supporting the idea of imposing a sanction on the specific attacker. There will be more and more attacks identified on a technical layer.

The Communication Policy

The next problem linked with the attribution is the communication policy. In the case of identifying the assailant, the authorities of the certain country and later the representatives of the EU need to consider the amount of information they intend to reveal. The scarce of technical details can lead to skepticism within the EU members and finish with the lack of any decision. What is more, the other international actors may question the outcome of the inquiry, but also it risks the long-term consequences where states accused other states of cyberattack without presenting evidence. On the other hand, the abundance of the information available to the public may risk intelligence techniques and assets of certain countries and may threaten the next operations. The policymakers in the EU need to find equilibrium between these two options.

Not only, there is a technical attribution of cyberattacks. There are also several theoretical models of attribution of attack based on the social and political background. One of them, Jason Healey’s methodology, consisted of 14 factors (see Table 1).

Table 1: The attribution theoretical framework

| Analytical Element | Bundestag | National Health Service |

| Attack Traced to Nation | Many traces to Russia | Many traces to North Korea |

| Attack Traced to State Organizations | Many Traces | Many Traces |

| Attack Tools or Coordination in National Language | ||

| State Control over the Internet | High | Very High |

| Technically Sophisticated Attack | Medium | Medium |

| Sophisticated Targeting | Yes | No |

| Popular Anger | Medium | High |

| Direct Commercial Benefit | Low | Assumed Very High |

| Direct Support of Hackers | Low | High |

| Correlation with Public Statements | Moderate | Very High |

| Lack of State Cooperation | Russia refused to cooperate | North Korea refused to cooperate |

| Who Benefits? | Russian government | North Korea economy |

| Correlation with National Policy | High | High |

| Correlation with Physical Force | Moderate | Moderate |

Source: Healey (2013), pp. 265 – 276.

The members of the EU can use this theoretical framework or modify it to combine the political attribution with the technical one. Every one of these two methods possess flaws and problems but together may create a credible and effective attribution mechanism, which would strengthen the possible EU sanctions regime for cyberattacks.

The Scenarios of Potential Sanctions for Cyberattacks

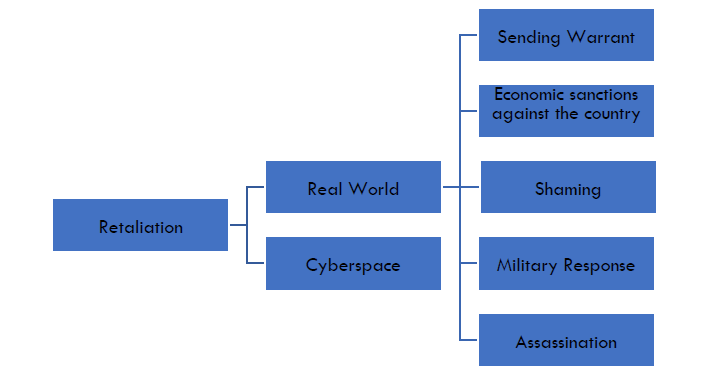

Even though the uncertainty linked with the identification process of assailant’s state authorities have already prepared a range of tools used to retaliate. A part of them could be observed in certain cases in the past. The others appeared only in doctrines and strategies and had never materialized in the real world. Generally, we can separate the retaliation in the real world and cyberspace. According to the international law, states should use proportionate measures, but it does not always happen.

Figure 1: The possible retaliation measures against cyberattacks

The most reasonable option should be answered in a virtual world by using similar tools and methods as the opponent. It could be response from single members, groups of members of the EU. In the past, several cases were illustrating the proportional retaliation. In 1999 during Kosovo war Serbian hackers attacked the NATO websites using the Denial Distributed of Service Attacks (DDoS). In response to Western hackers affiliated and sympathized with mission also orchestrated the flooding type attack on the Serbian administration website (Borger 1999). Similar cyber skirmishes happened during 2001 Chinese-American crisis over the crash between the Chinese jet and American spy plane or between the hackers of conflicting sides like Pakistan and India or Israel and Palestinian.

There is a slight difference in the Iranian attack on the United States banks in 2012. It was retaliation for the Stuxnet worm, which infiltrated the Natanan uranium enrichment facility and destroyed thousands of centrifuges. This computer program became the first inflicting damages in the material world (Zetter 2011). However, Iran’s abilities were too limited to conduct similar operation against the US and they decided to attack vulnerable sector – American banks (Volz and Finke 2016). This response was not proportional and was far less destructive and limited only to a digital world.

The retaliation in cyberspace is the most popular and probably will remain in the foreseeable future. The easy ways to carry out this kind of operations, the wide range of possible tools and the relatively small consequences in case of the mistake and last but not least the problems with attribution encourage actors to these actions. There are several weaknesses too. In most cases the damage would be minimal, probably the civilians would also be victims and there is also a threat of retaliation in cyberspace.

In the EU it will be hard to conduct such an operation. Firstly, only a small number of countries publicly announced the capabilities to perform the offensive operations. Among them are the Netherlands and Great Britain (Emmot 2018). Secondly, the EU and its members are not eager to use any offensive tools. Finally, it would be difficult to achieve a political agreement within the EU. So, this option could be used only by single countries or a group of countries, but the action from the EU as a whole is rather unimaginable due to the different potentials and willingness to engage in such an activity

Real World

For a long time the response to the cyberattack in the real world has remained only the deterrent tool recorded in different doctrines and strategies. But lastly the situation changed and there were many examples of sanctioning hostile cyber activity by economic sanctions, naming and shaming campaign or sending warrants for persons engaged in the hacking activity. There are several options of retaliation in the real world against cyberattack.

Military Response

The strongest and harshest way of response is to conduct the military strike against a country which conducts the hostile operations in cyberspace. This kind of operation never happened in history, but, e.g. the United States officially declared that among retaliatory options they might use military force (Spillius 2011). In Europe, Germany considers this option too (Koch and Riedel 2018). NATO declared officially in the Wales summit declaration that cyberattack could trigger the article V and therefore possible military reaction (NATO 2014).

Considering that the EU has the equivalent of NATO Article V, which is article 42.7 of the treaty of European Union on the EU’s mutual defence provision and it was even used after the terrorist attack in Paris in 2015 (Traynor 2015), the EU should consider a similar declaration to NATO. There is no need to provide a precise record of the conditions and situation of executing the military attack. It is commonly recognized as the response to a cyberattack with the magnitude comparable to a conventional attack with the death tolls. This kind of declaration should play a role of a deterrent factor and multiple available options rather than be considered as a feasible tool.

There is a little chance that the EU or the EU members would use own armed forces. First of all, devastating cyberattacks, which bring huge destruction and high death tolls are the part of Hollywood movies, which are far from reality now. What is more, the country that decided to conduct such a strike will change history because the consequences can be unimaginable and extremely politically costly. Furthermore, the EU has not had own armed forces and the armies of its members are relatively weak. Last but not least, there is weak political will for any military operations in the EU.

However, it may change in the future with the ambitious plans of German-France tandem to set up European army (Stone 2018). Therefore, such declaration should be announced that EU may answer with a conventional attack against cyberattacks.

Sanctioning Individuals

Arresting the cybercriminal was the first method used against persons engaged in hostile activity in cyberspace. In the 1990s, it was relatively easy because most of the attack was orchestrated from the domestic territory and was covered by national criminal law. In the 21st century, this situation has changed, and pursuing cybercriminals become more and more dangerous. However, the international and bilateral cooperation contributed to catching famous Max “Iceman” Butler and the Dark Market heads and this cooperation is still used and developed, e.g. under the Convention on Cybercrime.

But in 2014 the United States went even further and filed criminal charges against five Chinese military officers for stealing a trade secret. This kind of situation happened the first time in history and obviously could not achieve success, but it presented a determination of the US authorities and also the fact that they are more and more upset with increasing Chinese engagement in cyberspace activities. The government in Beijing rejected the accusations and obviously, the chances that these five persons will be sent to the U.S. are literally none, but it was a signal to the Chinese government to reduce their involvement in cyberespionage campaign and that United States government treats it seriously. It was later repeated against Iranian hackers (Denning 2017).

The members of the EU, but also the EU itself, can conduct similar activities. The Ministries of Justice of General Prosecutors may file criminal charges against officers of the foreign intelligence and issue arrest warrant. What is more, the EU can do the same through the Europol and its European arrest warrant. There are not the only available tools. The EU could also seize assets or ban access to own territory individuals accused or direct or indirect engagement in hacking. Yevgeniy Prigozhin – the head of Internet Research Agency could be banned from entering the EU territory after the next Russian interference in one of the EU countries. The other possible targets are the GRU or FSB commanders. This measure is available to the EU and was used in the past. Dozens of Russian citizens were sanctioned after the Crimean annexation (European External Action Service 2018).

Sanctions against the Company

In 2015, just before the last summit between President Obama and Chinese President Xi Jinping, the media speculated that the United States would impose sanctions against the Chinese companies, which gained the largest benefits from the cyberespionage campaign (Davis and Sanger 2015). Since that time, the Chinese companies Huawei and ZTE were banned from significant projects like building 5G infrastructure in Australia, India, and the United States. Other countries like Japan, the United Kingdom, Germany consider these firms as a possible threat to national security (Leonardo 2018).

The EU could ban certain companies from the EU market if it detects that they are engaged in espionage activity in the name of foreign intelligence state. There is the EU Air Safety List that includes all airlines banned from operating in Europe (European Commission 2018). It would be a good idea to create a similar list of producers of software and hardware if they threaten the security of the EU. Taking into consideration that the EU market is an attractive business target it could be an effective deterrence factor in the sanction regime.

Economic Sanctions against the State

Not only can the certain companies be punished by the economic sanctions but also the states. The first victim of such measures was North Korea, which was accused of a massive cyberattack on Sony and in consequences forced the company to withdraw comedy movie about the North Korean leader from the United States cinemas. Barack Obama’s administration decided to impose additional economic sanctions on North Korea and therefore setting precedence (Wroughton 2018). This decision was mostly symbolic as North Korea was imposed with multiple sanctions in the past and remained one of the most isolated countries in the world. But the American decision was more than just to punish Kim Dzong Un regime and should be understood as deterrence action illustrating the possible U.S. response.

The EU sanctions are one of the most dangerous weapons in a toolbox of this organization especially considering the scale of trade volume and investments in the EU. The EU sanctions harm Russia much more severe than the U.S. and Canada together (Rapoza 2017). Taking into account economic sanction, it would be probably the most damaging weapon in EU arsenal against states-sponsor cyberattack.

Implications and Lessons for the Future

Despite the political friction within the EU, the economic sanctions on Russia and travel bans on persons engaged in Crimea operation and a war in Eastern Ukraine have been maintained since 2014. Many pundits were skeptical about the abilities of the EU to first impose sanctions and later prolong them. What is more, these sanctions harm the Russian oligarchs and the Russian economy (Ćwiek-Karpowicz at al. 2015). It shows that the EU sanction regime could be effective and thus play a credible deterrent factor. Cyberattacks being a threat to every state, company and individual, it would be probably easier to persuade authorities of the countries to impose sanctions on hostile actors.

Considering the aforementioned options, it seems that the most probable tools that could be used are the sanctions against individuals both by banning them from entering the EU or by sending European Arrest Warrant. However, in the wake of the Ukraine crisis, the EU has shown determination and has imposed and maintained sanctions on Russian state and companies. This strong presentation of unity and strength has demonstrated the EU as the ambitious international actor. It means that the sanctions could also be used against the actors engaged in a hostile cyber activity. Considering the military response, which is on this moment is highly unrealistic, but the declaration like NATO should be issued. It gives the next tool in the sanction regime and taking into account the German and France plan to create the EU army, it may be more realistic in the foreseeable future.

Every sanction imposed on other country needs to be supported with credible intelligence. Thus, the EU needs to improve own intelligence capabilities and the exchange of information. There are already countries like the Netherlands, France, Great Britain with significant abilities to detect, identify and attribute cyberattacks. It would be crucial for other EU members to gain such capabilities but there should also be a forum, where countries could exchange details about cyberattacks, techniques and tools of assailants. Similar groups exist and are devoted to the problem of terrorism.

Last but not least, the sanction regime could deter state sponsor or state enabled attacks, but it would be utterly ineffective against non-state actors such as individuals’ hackers or group of criminals. The last breach of date in British Airways (Morris 2018) or Facebook breach (O’Flaherty 2018) were done by non-state actors showing the increasing capabilities of such actors. Therefore, alongside with developing the effective regime of sanction, the EU needs to strengthen cyberdefence of its members and institutions.

The article was originally published in The Visio Journal 3 (2018)

References

Borger Julian. 1999. “Pentagon kept the lid on cyberwar in Kosovo.” The Guardian, November 9. https://www.theguardian.com/world/1999/nov/09/balkans.

Davis, Hirschfeld Julie, and David E. Sanger. 2015. “Obama and Xi Jinping of China Agree to Steps on Cybertheft.” New York Times, September 25. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/26/world/asia/xi-jinping-white-house.html.

De Carbonnel, Alissa, and Robin Emmott. 2018. “Fearing election hacking, EU leaders to ready sanctions.” Reuters, October 18. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-eu-summit-cyber/fearing-election-hacking-eu-leaders-to-ready-sanctions-idUSKCN1MS2N3.

Denning, Dorothy. 2017. “Cyberwar: How Chinese Hackers Became a Major Threat to the U.S.” Newsweek, October 10. https://www.newsweek.com/chinese-hackers-cyberwar-us-cybersecurity-threat-678378.

Drozdiak, Natalia, and Nikos Chrysoloras. 2018. “U.K., Netherlands Lead EU Push for New Cyber Sanctions.” Bloomberg, October 11. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-10-11/u-k-netherlands-lead-eu-push-for-new-cyber-sanctions-document.

Emmot, Robin. 2017. “NATO mulls ‘offensive defence’ with cyber warfare rules.” Reuters. November 30, https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-nato-cyber/nato-mulls-offensive-defence-with-cyber-warfare-rules-idUKKBN1DU1GV.

European Commission. 2018. The EU Air Safety List. https://ec.europa.eu/transport/modes/air/safety/air-ban_en.

European External Action Service. 2018. EU sanctions against Russia over Ukraine crisis. https://europa.eu/newsroom/highlights/special-coverage/eu-sanctions-against-russia-over-ukraine-crisis_en.

Fruhlinger, Josh. 2018. “Top cybersecurity facts, figures and statistics for 2018.” Csoonline, October 10. https://www.csoonline.com/article/3153707/security/top-cybersecurity-facts-figures-and-statistics.html.

Goldsmith, John. 2017. “The Strange WannaCry Attribution.” The Lawfareblog, December 21. https://www.lawfareblog.com/strange-wannacry-attribution.

Healey, Jason. 2013. A Fierce Domain: Conflict in Cyberspace 1986 to 2012, Arlington: Cyber Conflict Studies Association.

Kaplan, Fred. 2016. Dark Territory: The Secret History of Cyber War. New York: Simon&Schuster.

Karpowicz-Ćwiek, Jarosław, at al. 2015. Sanctions and Russia. Warsaw: PISM. https://www.pism.pl/publications/books/Sanctions_and_Russia.

Koch, Moritz, and Donata Riedel. 2018. “Germany could dispatch armed forces in response to cyberattacks.” Handelsblatt, June 6. https://global.handelsblatt.com/politics/germany-soldiers-combat-cyberattacks-931929.

Leonardo, Luigi. 2018. “More countries consider banning Huawei and ZTE.” GadgetMatch, November 14. https://www.gadgetmatch.com/huawei-zte-5g-ban-australia-japan-uk-germany/.

Mandiant. 2013. APT1 Exposing One of China’s Cyber Espionage Units. https://www.fireeye.com/content/dam/fireeye-www/services/pdfs/mandiant-apt1-report.pdf.

Morris, Hugh. 2018, “British Airways data hack hits 380,000 recent customers.” Telegraph, September 7. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/news/ba-british-airways-data-hack-compensation/.

NATO. 2014. Wales Summit Declaration. Last updated August 30, 2018. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_112964.htm.

O’Flaherty, Kate. 2018. “Facebook Data Breach — What To Do Next.” Forbes, September 28. https://www.forbes.com/sites/kateoflahertyuk/2018/09/29/facebook-data-breach-what-to-do-next/#57ba903f2de3.

Rapoza, Kenneth. 2017. “Here’s How Europe’s Russian Sanctions Differ From Washington’s.” Forbes, June 23. https://www.forbes.com/sites/kenrapoza/2017/06/23/heres-how-europes-russian-sanctions-differ-from-washingtons/#18e79a6a5161.

Spillius, Alex. 2011. “US could respond to cyber-attack with conventional weapons.” Telegraph, June 1. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/northamerica/usa/8550642/US-could-respond-to-cyber-attack-with-conventional-weapons.html.

Stone, Jon. 2018. “EU army: Brussels ‘delighted’ that Angela Merkel and Macron want to create European military force.” The Independent, November 14. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/eu-army-angela-merkel-macron-germany-france-military-european-commission-juncker-a8633196.html.

Traynor, Ian. 2015. “France invokes EU’s article 42.7, but what does it mean?” The Guardian, November 16. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/nov/17/france-invokes-eu-article-427-what-does-it-mean.

Volz, Dustin, and Jim Finkle. 2016. “U.S. indicts Iranians for hacking dozens of banks, New York dam.” Reuters, March 24, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-iran-cyber/u-s-indicts-iranians-for-hacking-dozens-of-banks-new-york-dam-idUSKCN0WQ1JF.

Wroughton, Lesley. 2018. “U.S. Treasury sanctions North Korean hacker, company for cyber attacks.” Reuters, September 6. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-cyber-northkorea-sanctions/u-s-treasury-sanctions-north-korean-hacker-company-for-cyber-attacks-idUSKCN1LM2I7.

Zetter, Kim. 2011. “How Digital Detectives Deciphered Stuxnet, the Most Menacing Malware in History.” The Wired, November 7. https://www.wired.com/2011/07/how-digital-detectives-deciphered-stuxnet/.