Russia’s economic landscape is under strain. In this interview, Martin Vlachynsky, an analyst from INESS, sheds light on the complexities of Russia’s current economic policies, their implications for businesses and ordinary citizens, and how the ongoing war continues to shape the country’s financial reality.

In Russia, the base interest rate is 21 percent; it is estimated that loans to small and medium-sized enterprises will be at 30 percent next year. What will this mean for companies? Is it possible to do business normally with such expensive capital, and can we expect a slowdown in investment?

Martin Vlachynsky: No interest rate can be said to be high or low without the context of the circumstances. The central bank interest rate is a monetary policy instrument that is applied with some purpose and some effect. Moreover, the Russian economy is in a very specific state. The part of the economy directly linked to the war is experiencing a big boom, but at the same time, it is draining resources and the rest of the economy is languishing.

An increase in the interest rate will, of course, lead to an even greater slowdown in investment in the civilian economy. However, the Russian Central Bank has assessed such a move as a better alternative to the threat of even higher inflation. Time will tell whether this was a good decision and whether it will be enough. Nevertheless, changing interest rates will not solve the fundamental problem that 7-10 % of the economic value created each year “burns up” in Ukraine.

What will this mean for ordinary Russians? Will consumer credit and mortgages go up? Can we expect a slowdown in consumption?

Martin Vlachynsky: Russia’s economic policy is schizophrenic, with the government stepping sharply on the monetary brake with one foot and on the fiscal accelerator with the other. Yes, higher interest costs will make credit more expensive and will curb consumption and investment. But at the same time, the government is directing large amounts of budgetary resources either to the purchase of arms, which is a fiscal stimulus for industry, or, through recruitment allowances, wages, and death allowances, directly into the hands of the population, thereby stimulating demand.

Inflation is approaching 10 percent. Is this already a problem and can the data from Russian statisticians be trusted?

Martin Vlachynsky: In such a specific economic situation, I would have a problem relying even on honestly measured and calculated statistics, let alone those that are firmly under the control of a totalitarian regime. If we look at alternative methods of estimating inflation, whether the GDP deflator, the change in the price of fast-moving goods, or an estimate of the real interest rate, we will see higher inflation.

Russian economic growth is set to slow to 1.3 percent in 2025 from 3.6 percent this year. Is this a sign of trouble and can we no longer talk about an overheated economy thanks to armaments?

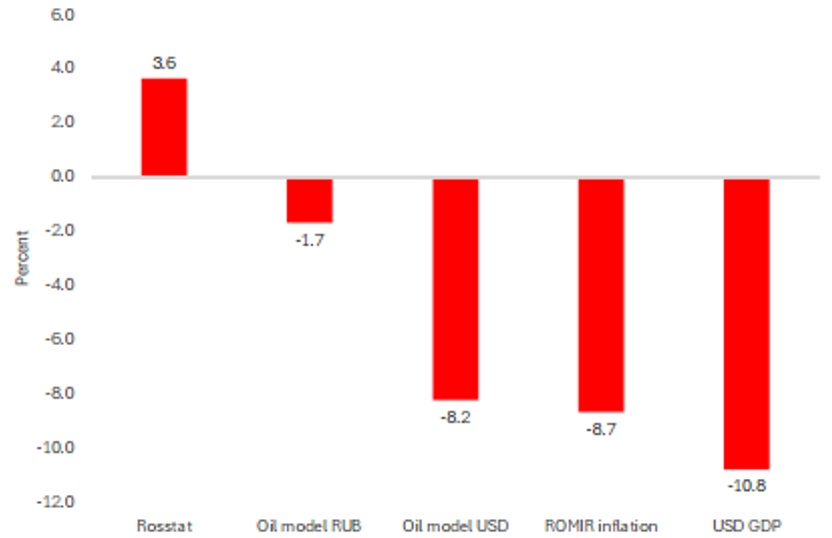

Martin Vlachynsky: The calculation of the GDP growth rate depends in no small part on the ability to measure inflation well. Alternative methods of calculation show that Russia may already be in a deep recession.

Figure 26. Alternative measures of GDP growth in 2023

However, this is not so much related to the issue of overheating. “Overheating” of the economy means that the economy is operating above its long-run potential.

Example: I will send half the peasants and their tractors to war. The country’s potato production potential will therefore be halved. At the same time, these new soldiers send home high salaries. But the demand for potatoes will not fall; consumers will want to eat them anyway. This will lead to a rise in their prices.

This is exactly the case in Russia: the demand for goods and services has not fallen, it has rather risen (due to the demand for weapons and higher incomes of the population), but the productive capacity has fallen (lack of employees, sanctions, etc.). This leads to overheating. Very simplistically, we can think of war as an economic program of digging and burying holes. It puts people to work and it shows up in the GDP statistics as construction activity, but it is clear to everyone that this is not a sustainable and workable economic system in the long term.

Unemployment in Russia is low, below three percent. Does that mean that the economy is fine?

Martin Vlachynsky: At least a million men of economically active age are at the front/wounded/crippled/dead/running away. At the same time, there is high demand in the economy. It would be art if unemployment were to rise in such a situation.

Is there anything that compares the state of the economy in Russia and Ukraine? In Ukraine, for example, interest rates fell from 25 to 13 percent between the summer of 2023 and June. Are there not similar problems there with an overheated economy?

Martin Vlachynsky: There is a comparison. But the difference is at least two things. The first is that the Ukrainian economy in February 2022 experienced a much bigger shock than the Russian economy, and the economic statistics deteriorated very sharply. They are therefore being compared today with the 2022 and 2023 lows, which may then look different in relative terms.

The second factor is that Ukraine gets some of its capital, and in-demand goods (especially arms and ammunition), for free from the outside, which changes the math a bit. But the basic point is also true here – the Ukrainian economy is experiencing a huge fiscal stimulus, even more than Russia. Roughly a third of Ukraine’s economy today is defense services.

Interview with Martin Vlachynsky, INESS analyst, for SME daily (October 30th, 2024, full length)

Continue exploring:

Unlocking Growth in Bulgaria: Medium-Term Goals After Election

Business Climate in Ukraine in September 2024: Trends, Challenges, Prospects