People assign meaning to various things: love, career, money, fame, power, work, appearance, or well-being. Especially the latter has become very fashionable – taking care of your own well-being, as if the resulting complacency would lead to something special and outstanding.

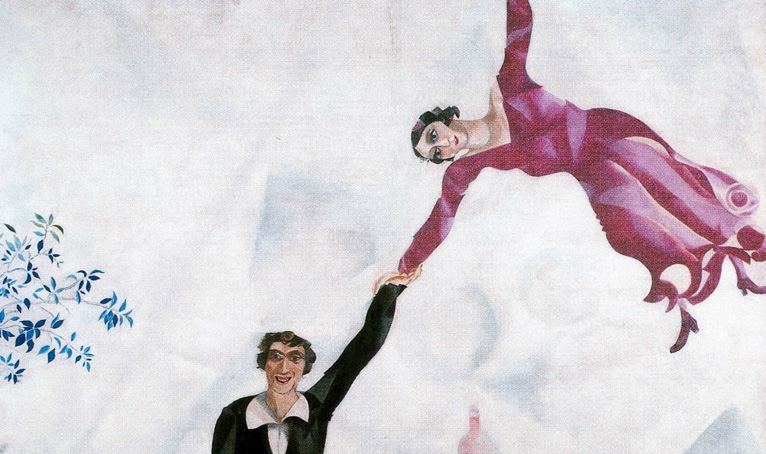

Meanwhile, in the course of our lives, three most important things emerge, sometimes dramatically, sometimes at a slow pace, which are worth our attention, time, and energy. Discovering them is no real revelation, but it seems as if they have been covered with the dense dust of oblivion and suffocating egocentrism. It is love – the first, second, third, first and only, last.

Loving, experiencing love, and being in a relationship with another human being. This is the key thing in life. Do you agree, Ladies and Gentlemen? Are there any objections?

The second important thing, intertwined with the former, is… another person. The close one and the stranger. The one we pass by, walking in the direction we have chosen, the one who extends his hand to us seeking help, the one who joins us on a park bench, and from that moment – as the Jewish philosopher, Martin Buber, said – we become responsible for them. The marginalized and the excluded, the underdog that Alicia Keys sings about.

What is more important than another human being? Me alone? Myself? If it was only me, it could lead to comfort, conformism, neurosis, depression, dissatisfaction with life, thinking about my own pain, frustration, or lack of purpose. Another person detaches us from ourselves and awakens the potential of unlimited possibilities that has been in us since the very beginning.

The third thing worth our attention, after which there is nothing for a long, long time, is the Holocaust. Remembering it, understanding its painful importance, and the lessons it gives us about thinking, sensitivity, and human nature. The memory of human suffering, which today is displaced by contemporary culture, because it does not fit into the paradigm of hedonistic happiness, causes discomfort and the feeling that something needs to be done. While it is best to do nothing.

It is also a memory of what a person is capable of – both in the sense of transgression, that is, exceeding oneself and rising above what has been experienced, and in the sense of cruelty of which a person is capable.

All these categories actually boil down to the two most important ideas that became the slogan of the culture of the 1960s and 1970s, and which are still functioning today. It is love and peace. Peace & Love!

Many societies, especially after the Second World War, believe that these ideals make sense and are worth pursuing. The result of this way of thinking is the state of actual peace in a given country. No More War, scream slogans after WWII and the Vietnam War.

Nevertheless, in 1995, the greatest genocide after the war took place in Srebrenica. And the world has been watching and doing nothing about it. How was it possible? A year earlier, in 1994, there was a massacre of the Tutsi minority. After these events, we promised ourselves that there will be no more war… until the next one.

In the years that followed, the wars in Iraq, Pakistan, and Afghanistan, as well as the war in Syria bear witness to our helplessness. But this helplessness is only apparent. Work for peace begins in childhood, at school, at home, and in upbringing.

War is still present in our lives, in the language we use, in games for children and young people that adults provide them with, in communication between adults, in the labor market, in the way we talk about others, in front of others, with children…

In each subsequent generation, we reproduce the reality of violence. Specific toys, such as guns and toy soldiers, computer games aimed at causing harm to another being and not bringing joy, the words we say – all this plays a role in shaping the reality in which we live, in which the next generations will live.

If someone is aware of this and works with children or young people, they are very lucky – because they can and should, because we already know that nothing else makes much sense – to shape the next generations on the way to peace and love.

The same is done by theater, cinema, literature, and art in general – “they shape the conscience of a new man”, to quote from my colleague’s theater play, Snake’s Skin. Actions for peace should always be supported – in terms of economy, politics, marketing, and business, all those areas which – so far focused primarily on profit – can now embody the ideals of love and peace.

If anyone would like to find out more on this topic, I would like to start by recommending the writings of Paulo Freire, a Brazilian educator, creator of emancipatory pedagogy, and the author of the illustrious book Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1968)

Meanwhile, let us go towards the light. Together.

Written by Natalia Wilk-Sobczak

The article was originally published in Polish at: https://liberte.pl/w-strone-swiatla/

Translated by Olga Łabendowicz

Continue exploring:

Statement by Polish Civil Society Organizations on Takeover of Ombudsman Office by Sejm Majority