The voting day in Ukrainian presidential elections passed rather calmly, and observers have not reported major electoral fraud, stating that basic standards of free elections were safeguarded1. Hopefully the same will apply to the second round on April 21, 2019.

The final result of the first round comes as no surprise since the polls had done a good job predicting the outcome, although the gap between the two leading candidates proved to be larger than it was expected.

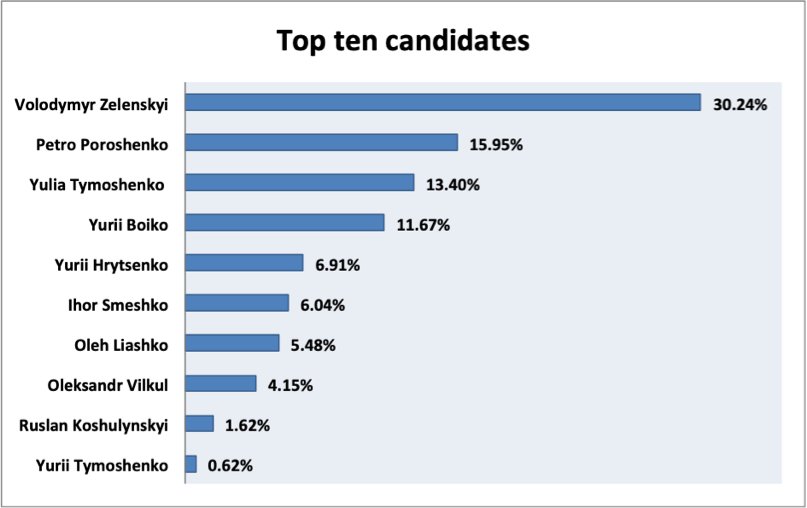

The convincing victor was the comedian and TV-producer Volodymyr Zelensky with 30.2% of votes against the incumbent president Petro Poroshenko, who secured only around 16%. Yet, Poroshenko stays in the game after eliminating one his major rivals, Yulia Tymoshenko (13.4%), who had directed her criticism mainly against Poroshenko while avoiding confronting Zelensky.

Source: Central Election Commission of Ukraine; official results of the elections (07.04.2019)

Source: Central Election Commission of Ukraine; official results of the elections (07.04.2019)

The only pro-Russian candidate in top-five, Yurii Boiko, came fourth (11.7%) beating Anatolii Hrytsenko (6.9%). The rather a low result of Hrytsenko could be explained by the performance of Ihor Smeshko, ex-head of the Security Service during the late Kuchma and early Yushchenko presidencies.

Smeshko was not a public political figure until recently and did not conduct a massive expensive campaign, but profited from airtime provided by several TV channels.

Who Is Mr Zelensky?

The political newcomer Volodymyr Zelensky officially started his campaign on a New Year’s Eve. However, he was preparing his electoral base for the last three years by performing in a TV show titled “Servant of the People” as an ordinary teacher of history who accidentally becomes a president, launching the fight against the corrupt political establishment.

As a result, Zelensky united those who are tired of the ‘old faces’ in politics, became disillusioned with Poroshenko, and frustrated with the ongoing war. He gained support of substantial part of the country’s East and South, as a fresh alternative to traditional pro-Russian candidates such as Yurii Boiko and Oleksandr Vilkul.

There was also Zelensky’s electoral success is also explained by a substantial increase in turnout in those regions, combined with an unusually weak turnout in the Western parts of Ukraine, the electoral base of Poroshenko.

In addition, Poroshenko has abandoned anti-corruption and deoligarchization rhetoric during the campaign, while his conservative slogans “Army, Language, Faith” did not resonate with the more centrist electorate.

Also, contrary to some forecasts, the electoral core of Zelensky — the youth — did come to polling stations. Additionally, Zelensky could have attracted parts of Tymoshenko’s traditional electorate (for instance, pensioners in the Central regions). Consequently, while Zelensky did not break the record of Poroshenko who won in all regions back in 2014, he came first in 19 out of 24 oblasts, as well as in Kyiv.

Thus, the proverbial electoral East-West divide was absent for the second consecutive time, while a new cleavage between the generations emerged instead.

However, this wide support of Zelensky across Ukrainian society seem to have been due first of all by the vagueness of his programme and ambivalent statements appealing to the electorate with different views. Everyone sees in Zelensky what they want to. Except for a few cases, he has avoided open conversations with journalist in real time, thus making impossible to clarify his position on the number of issues.

Instead, Zelensky communicates with the public by posting short videos via social networks and by touring with support from his TV comedy shows across the country. One of his slogans — “no promises, no excuses” — sums up his appeal to hearts rather than minds of citizens.

But one of the biggest concerns about Zelensky is his lack of political experience and policy expertise, especially in the field of foreign policy and national security. For instance, his programme does not mention the EU membership as a goal and, until recently, the candidate was quite sceptical about the need to pursue this course.

However, his representatives keep stressing that Zelensky is “100% pro-European” candidate and stands for the Association Agreement’s implementation2.

At the same time, following a request from journalists to name concrete steps to reinforce this process, his headquarters mentioned the establishment of the Office on European Integration within the government, a body that already exists since 20143. Zelenkyi is also in favor of NATO membership but stresses that the decision to join the block has to be approved on a referendum.

Zelenkyi’s discourse as a real-life candidate often does not coincide with that of his fictional alter ego Holoborod’ko.

For instance, in his show, the West (including IMF) is depicted as a powerful club that does not want to see Ukraine as a developed and independent country. This mirrors anti-EU conspiracy theories, particularly popular in Russia. Thus, Holoborod’ko decides to get rid of the country’s external debt and gain independence by calling all citizens to donate their savings.

Nevertheless, this narrative does not prevent Zelensky from making a commitment to continue cooperation with the IMF when he met with its representatives.

Another issue is Zelensky’s attitude towards the conflict with Russia. While not accepting the annexation of Crimea and recognizing Russia as an aggressor that has to pay back for destruction it caused, Zelensky naively thinks that direct dialogue with president Putin will move the conflict closer to an end. Although recently he has clarified that negotiations should be conducted in the presence of Western partners.

It should be noted, that the candidate suggests expanding the Minsk format by including the US and the UK into talks. But he falls short in clarifying what the next steps should be.

On a more positive side, Zelensky praises the US special representative Kurt Volker’s plan on a gradual deployment of the UN peacekeeping mission in the occupied parts of the Donbas.

Finally, there is concern that Zelensky is not an independent candidate, but working in the service of one of the Ukrainian oligarchs, Ihor Kolomoyskyi, whose TV channel broadcasts the candidate’s shows.

Although the latter has spoken favorably about Zelensky as a symbol of generational change, both dismiss such accusation. But some facts, such as the use of transport registered on the oligarch’s companies and Kolomoyskyi’s security staff by the candidate, point on more than a close business connection between the two.

Despite the fact that Zelensky has several reformers as advisers (ex-Economy Minister Aivaras Abromavicius and former Finance Minister Oleksandr Danyliuk, for instance), it is yet unclear who constitutes his core team.

Zelensky’s leading political consultant worked for the Party of Regions in 2006-2010, while the candidate’s campaign fund received official donations from people closely affiliated with ex-president Yanukovych (for instance, notorious lawyer and ex-deputy head of presidential administration Andrii Portnov)4. This casts a shadow on the Zelensky’s image as a new and independent political actor.

When it comes to the future policies of Zelensky, his team has briefly indicated several priorities. Among those: adopting new electoral code before October parliamentary elections, the transformation of the judiciary system, reset of the State Security Service and Prosecutor’s Office, re-launch of anti-corruption bodies (in particular, the Specialized Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office), the establishment of Financial Investigation Service.

Many of these points echo the demands of various pro-reform civil society organizations which indicates that they managed to persuade Zelensky to adopt their agenda, at least for now.

Nevertheless, the candidate keeps delaying presentation of the members of his potential team to be in charge of relevant policies, as well as more a concrete plan of actions during the first months of presidency.

Although recently Zelensky headquarters has published the list of steps to fight corruption, including establishment of an International Supreme Economic Court and depriving various law-enforcement agencies powers to investigate economic and financial crimes. However, many of these cannot be implemented without the support of the Rada.

Show Must Go On

This last week the entertaining element of the process gained momentum. In reaction to Poroshenko’s request for public debates, Zelensky issued a well-made video where he invited Poroshenko to engage in debates at the biggest stadium of the country in front of cameras and thousands of citizens.

In addition, he put forwards several conditions such as holding of simultaneous drug and alcohol test. Surprisingly, the president agreed, and what the country has witnessed consequently was a series of video exchanges between candidates that resulted in a medical examination of both candidates in front of cameras, though in different labs.

What is important, in the two weeks before the vote, the citizens are not discussing the substance of political programmes anymore, but rather the debate about debates.

The majority of the eliminated top candidates have abstained from supporting either of the two remaining.

However, according to surveys conducted before the first round, 47% of Tymoshenko voters would rather support Zelensky compared to only 11% of her supporters are ready to vote for Poroshenko. Pro-Russian voters of Boiko and Vilkul are also expected to support the showman, while the votes of Hrytsenko and Sushko could be spread equally between the candidates.

Overall, these tendencies seem to favor Zelensky.

One could assume that many in the post-Soviet area follow the Ukrainian elections with envy given the high competition between politicians taking place in a public sphere involving considerable parts of the population.

However, the risk of polarization of the society due to hatred in political debates has risen substantially and could weaken the country. This makes open public debate between the candidates vital for Ukraine’s future, since it would allow the voters to assess what each of the competitors stands for in terms of foreign and domestic policies, as well as to define a common set of non-negotiable principles to guide the future presidency, whoever becomes the next head of state.

The article was published as 3 DCFTAs Op-ed No 10/2019, March 2019 on http://3dcftas.eu

The publication was prepared within the framework of the core support programme to CEPS-led 3DCFTAs project, enabled by the financial support from Sweden.

Views, conclusions or recommendations belong to the authors and compilers of this publication and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Government of Sweden. The responsibility over the content lies solely with authors and compilers of this publication.

1Statement of Civil Network OPORA on Preliminary Results of Observation at the Presidential Election in Ukraine on March 31, 2019 (April 1).

2https://www.unian.info/politics/10505385-ukrainian-election-frontrunner-s-adviser-zelensky-s-course-to-be-100-pro-european.html

3https://www.eurointegration.com.ua/articles/2019/03/25/7094332/

4https://www.chesno.org/post/975/