The current pandemic and the previous lockdown had effects on several areas of life, including work and social life. However, there is a rather neglected sphere which is rarely discussed in the media compared with other topics. Reproductive health issues were already marginalized all over the world before the virus breakout, including abortion rights, accessibility of contraception and giving birth.

As the pandemic deepened existing social inequalities – reproductive freedom being no different – access to abortion has been restricted in several countries. This article aims to uncover the issue and broaden understanding on yet another gendered effect of COVID-19.

To understand why a pandemic and the lockdown could harden access to abortion, one has to consider the process of requesting termination of pregnancy in most countries. There are two methods used for abortion, the surgical process, and medical abortion with mifepristone and misoprostol pills.

Typically, the pills are only allowed to be taken during the first trimester, after that the pregnancy has to be terminated surgically. In the majority of European countries both methods are available, however, there are also exceptions, i.e. Hungary, where the surgical abortion is the only possibility for those with unwanted pregnancies.

The time limit for a legal abortion varies among countries, but most commonly it is around 3 to 6 months. During the process of requesting an abortion, women will be examined first, and signatures from one or more health care professionals will also have to be provided. Due to limitations of health care systems, there is a waiting period after getting approved for the process, which can vary depending on available medical care.

One of the main issues when examining accessibility of abortion is time constraint. It is not uncommon that women only realize they are pregnant around the end of the first trimester. The reason behind this could be young age, misinformation from health care professionals, or lacking access to information, as well as irregular periods causing the pregnancy to be less apparent.

Women affected by this issue will either be too late for getting a legal abortion, or still be on time, however, in the second case long waiting periods can still delay access.

This problem causes women to travel in hope of accessible abortion, even when it is legal in their own country, but is inaccessible for them due to legislation on time limit. However, travel restrictions caused by the coronavirus pandemic resulted in this option becoming unavailable for many.

This highlights the necessity of governments implementing regulations which allow women to have safe abortions in their own country, which could be achieved by increasing the number of reproductive health care professionals to shorten waiting period and by less strict time limits for termination of pregnancy. In spite of this, no European country expended its gestational limit for abortion.

Furthermore, surgical abortions were less available in 12 European countries during the pandemic, and there are 11 countries where women with COVID-19 symptoms were denied access to abortion, or services were delayed for them. These numbers help understand another problematic aspect of abortion accessibility: availability of medical abortion, as it is more convenient and easier to provide, compared with the surgical process.

Fortunately, there are positive examples as well: in the United Kingdom telemedicine has become available, which allows patients to access online clinical care. England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland have also permitted abortion pills to be home-delivered during the pandemic, which allows for a safer and psychologically less challenging way of terminating a pregnancy.

However, the option of self-managed abortion should not be a temporary solution during the pandemic. The problem was brought to light due to the limitation of personal contact between patient and doctor becoming necessary, but it is not the only reason to permit taking the pills home. Self-managed abortion increases self-determination of women and provides a convenient environment for a possibly challenging process, and it could be a step towards decriminalizing abortion.

Considering the increasing demand for self-managed abortion, it is also important to mention that this process would also be part of a wider ‘ecosystem’, where after choosing the option of self-management, checking in with a doctor may also be necessary, for instance to confirm that the pregnancy has indeed ended. Focusing on the issue by taking it out of its wider context may not reflect many women’s path who still need support and consultation from health care professionals.

Unfortunately, many countries do not prioritize accessibility of safe abortions, in Hungary – where surgical abortion was the only available method for ending an unwanted pregnancy – non-lifesaving surgeries were suspended in 2020, which banned the only legal way of ending a pregnancy in the country.

The problem of inaccessibility of safe abortion is not unique to European countries. According to Marie Stopes International, almost 2 million fewer women have accessed contraceptives between January and June. The same report also predicts 900,000 unplanned pregnancies and 1.5 million unsafe abortions over the world. In India 1.3 million fewer women accessed contraceptives, and according to an Ipsos MORI survey, approximately 30% of respondents tried to seek abortion.

However, due to the increased demand for abortion pills, a shortage has also been created, which might have something to do with the fact that 9% of these women reported a more than five-week-long waiting period.

Despite pro-life arguments proposing to ‘save the fetus’ by banning abortion, or making it less available, in many cases lacking access to safe abortion does not result in giving birth to a healthy new-born. In Kibera slum, a neighbourhood in Nairobi, Kenya some women attempted to end their unwanted pregnancies by using broken glass and sticks and pens, two of them died from their injuries. According to the Guttmacher Institute, abortion rates in countries where termination of unwanted pregnancies is illegal is similar to countries where abortion is legalized.

However, in parts of the world where it is banned, unsafe abortions cause 8 to 11% of maternal deaths (approximately 30 000 every year). Despite 97% of self-induced processes occur in periphery countries, the phenomenon is not unique to this area. In Europe, there are more than half a million unsafe abortions annually. These numbers illustrate the importance of providing safe abortions to avoid life-threatening home procedures.

Beyond disrupted supply chains for both abortion pills and contraceptives, inaccessible health care due to the lockdown, and restricted travelling, there is another reason why the state of women’s right to self-determination was yet again damaged. The collective uncertainty created by the unprecedented (for generations living today) pandemic and lockdown situation, and the disruption of social life was used by several governments to implement new regulations which have nothing to do with the pandemic.

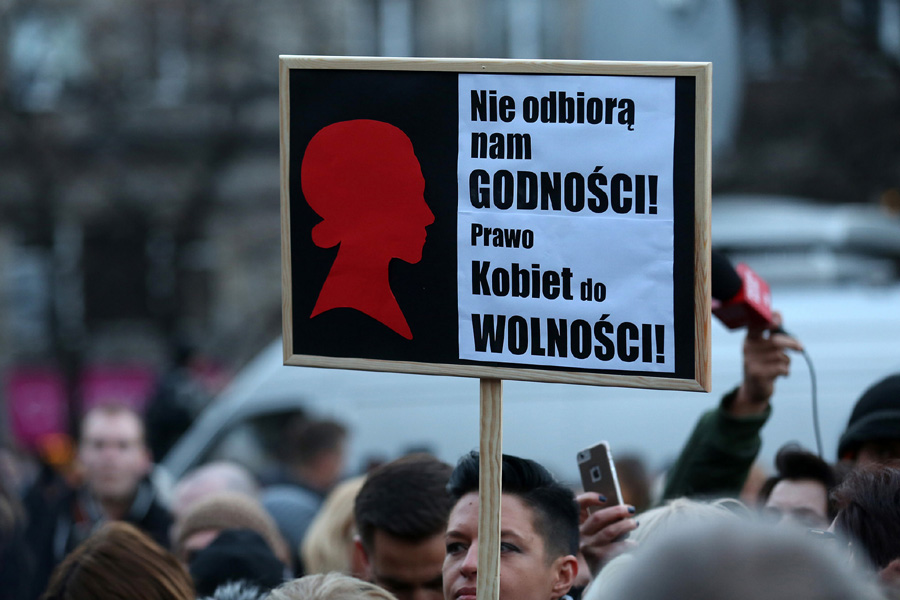

As it was mentioned before, abortion was suspended in Hungary during COVID-19, however, this is not a standalone incident, in the past year abortion was banned in six European countries, Andorra, Liechtenstein, Malta, Monaco, San Marino and Poland.

Perhaps the new Polish regulations that were the most frequently discussed by the media. Before the new regulation women could only access abortion based on three grounds: the pregnancy is a result of a criminal act (rape), when the pregnant woman’s life or health is at risk, and in the case of foetal defect. By banning the third option, the Polish government made the ground most commonly used for termination of pregnancy illegal.

The legal ban on abortion combined with the inability to travel puts women in the above-mentioned countries in a highly challenging situation. Especially, because – as it was mentioned before – supply chains for contraceptive pills are disrupted due to the pandemic, making it harder to prevent the unwanted pregnancies.

Beyond ‘abortion tourism’ (travelling to a foreign country for the purpose of accessing abortion), there is another option for women wanting to end their pregnancies outside of the health care system of their country: there are websites providing abortion pills that can be ordered online and have home-delivered.

In the US, Aid Access also provides online consultation for women with unwanted pregnancies, and for Europeans there is Women on Web, which aims to help those who cannot access safe and legal abortion in their countries. Those living in areas where abortion is legal (but sometimes hardly available), can buy the pills, whereas women living in periphery countries can access them for free, or at a lower price.

However, for underprivileged women in Europe or in the US, these pills can have a high price, therefore are hardly purchasable.

Furthermore, because supply of mifepristone and misoprostol is often ensured by Indian pharmacies and the time for a package to be delivered has also increased during the pandemic, this option is not reliable.

Due to the previously mentioned reasons, an increased number of women with unintended pregnancies could not access abortion pills on time, or for different reasons chose not to terminate their pregnancy, statisticians are debating whether a baby boom could be expected. Beyond the obvious emotional challenge of an unwanted pregnancy, the financial consequences also have to be taken into consideration.

If an increasing number of women will give birth under difficult financial circumstances (women who live in developing countries, or recently became unemployed), it can aggravate their financial problems, furthermore, their children could lack access to services, such as quality medical care. A baby boom resulting from the lockdown under the pandemic could have serious effects on inequalities, further widening the gap between the wealthiest and the underprivileged.

Continue exploring:

Death by Thousand Cuts: Erosion of Media Independence in Poland