The spectrum of hate speech is very broad, varying from hatred to extremely abusive forms of prejudice. Oxford English Dictionary defines hate as “an emotion of extreme dislike or aversion; detention, abhorrence, hatred”. And often the qualification of an action as “extreme” is treated as a decisive parameter in defining hate speech.

From a legal perspective, the hate speech spectrum stretches from types of expression that are not entitled to protection under international human rights law, to types of expression that may or may not be entitled to protection, depending on the existence and weight of a number of “contextual variables” (e.g. extremely offensive expression), to other types of expression that presumptively would be entitled to protection despite their morally objectionable character (e.g. negative stereotyping of minorities).1

One of the definitions of hate speech can be found in Recommendation No. (97) 20 of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe:

(…) the term “hate speech” shall be understood as covering all forms of expression which is used to spread, incite, promote or justify racial hatred, xenophobia, anti-Semitism or other forms of hatred based on intolerance, including: intolerance expressed by aggressive nationalism and ethnocentrism, discrimination and hostility against minorities, migrants and people of immigrant origin.

One more definition that does not come from a legal text is as follows:

Hate speech is any speech, gesture or conduct, writing, or display which is forbidden because it may incite violence or prejudicial action against, or by a protected individual or group, or because it disparages or intimidates a protected individual or group. The law may identify a protected individual or a protected group by certain characteristics.

This understanding of hate speech includes publications, symbols, graffiti, songs, movies and radio broadcasting. This definition will be accepted as the official one in this report. It is broad and implies that hate speech cannot be left alone, and action must be taken against it.

Hate speech is growing in Europe. The years after economic crisis brought new antagonisms in the European Union. The rich against the poor, the locals against the new-comers, the South against the North… Antagonisms bring conflicts and conflicts bring hate speech. New surveys and researches show that the extremists are on the wave. Especially those from the far right who build their identity and programme on hatred, xenophobia, anti-Semitism and many other phobias. They introduce hate speech to mainstream discourse, both in politics and media. And the latter ones influence a lot the speech of regular people.

The ultimate confirmation of the trend was remarked during the elections to the European Parliament in May 2014. Eurosceptic right-populist parties increased their vote share from 11% to 15%, with some countries receiving even more support. Lega Nord in Italy, Austrian Freedom Party, Jobbik in Hungary, Party of Freedom in the Netherlands, True Finns, and Congress of the New Right in Poland have now marked their representation in Strasbourg and Brussels. Danish People’s Party, National Front in France and the United Kingdom Independence Party won the elections in their states, scoring respectively 26%, 25% and 27% of votes. The National Democratic Party of Germany and the Golden Dawn of Greece, two parties considered neo-nazi also won seats for their MEPs. The last case is especially alarming because the Greek party (associated with a swastika-like symbol) promotes political violence, being under investigation for brutal crimes, and their leaders facing incarceration. This proves that the radical right present in the European Parliament is thus not only the so called “far right 2.0”, the one with more aesthetic look and rhetoric traits, but also includes the traditional far right that bases its support on racism, anti-Semitism, skinheads, etc.

Hate speech is one of the aftermaths of the development of extreme right movements in Europe. It is organically connected with nationalistic demagogy, with both phenomena feeding on each other. Hate speech reflects a negative attitude represented by nationalists towards different groups, and, on the other hand, hate speech becomes the nutrient for far right movements that institutionalize aggressive discourse. This is the classic knock-on effect, which can also be observed in the relationship between hate speech and hate crime. Therefore the fight against hate speech contributes to the fight against nationalism, which implies that focus on the topic is required from the liberal front.

Hate speech has become a typical behavior among politicians. More than 40% of respondents in a research dealing with this issue said that the use of offensive language towards LGBT people by politicians is widespread in their country. In some countries it went up to above 90%. On an average, 44% of respondents across the eight countries surveyed said that anti-Semitism in political life is a big problem. In some countries, this figure rises to well over 50%.

Political hate speech is connected with hate speech in media. The same survey shows that in those countries in which the respondents reported a high degree of anti-Jewish sentiment, there is also a heavy presence of anti-Semitic reporting in the media. This research appears to have identified an interaction between the media and the politics, that requires further investigating.2

Hate speech in Central Europe

Hate speech in the Eastern Europe has some specific features, especially when compared with the Western Europe. It is of course connected with the specific socio-economic situation that was determined by the common historical experience, built on the trauma of World War II and the communist era, with a strong role of the Christian religion in its more ludic and conservative version. The countries that were closed and partly isolated from the outside world developed different societies, that were more homogeneous, with specific national, ethnic and religious tensions.

As Andras Sajo observed:

After all, racism and incitement to hatred against ethnic (national) groups (primarily but not exclusively minorities) present a major social and regulatory problem in the post-communist period. Extremist nationalist propaganda has often been part of the self-assertion of nationalist political movements and become part of official government ideology. Extremist nationalist speech played a major role in the escalation of the Yugoslav conflict, contributing ultimately to genocide. Given the strong endorsement of nationalism by many political actors, including some governments, in many countries extremist speech, irrespective of the legal provisions, became, to some extent, socially normalized.3

It can be noted that hate speech in Eastern Europe targets some specific groups. Roma people, LGBT and Jews can be pointed out here. However, the reasons for that are very complex and explaining them lies beyond the scope of this article.

High level of discrimination against Roma people has been reported in many studies.4 Hate speech against Roma is permanently present in public discourse of Hungary, the Czech Republic, Slovakia or Romania. The media build a negative image of the Roma. Also the politicians do not avoid spreading hatred. An example of a Hungarian mayor can be quoted here. He once said “The Roma have no place among human beings. Just as in the animal world parricides must be expelled.”5 It is difficult not to see the connection between hate speech and other hate crimes here. For example, in Hungary between 2008 and 2009 six Roma people were killed with “Molotov cocktails” thrown at their houses, and they were shot as attempted to flee.6

Central and Eastern Europe is also deeply homophobic7 and it is reflected in the hate speech. 23% of Croatians, 22% of Bulgarians and 21% of Romanians believe that homophobic harassment and assault are very widespread in their countries. Slovakia, Poland, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia come next.8 Countries of the region “won” also when their citizens were asked about how widespread offensive language about lesbian, gay, bisexual and/or transgender people by politicians is in the country where they live (Lithuania 58%, Bulgaria 42%, Poland 33%), hatred jokes in everyday life (Bulgaria 68%), aversion towards transgender people in public (Bulgaria 47%, Croatia 42 %, Lithuania 41 %).9

The International Network Against Cyber Hate and the Paris-based International League Against Racism and Anti-Semitism released a report documenting the explosion of online anti-Semitic hate speech. It is a trend observed in all of European Union, but while in the West it is connected with the war between Israel and Hammas, in the East it is still an aftermath of the stereotypes and experience of the war and communism. In a poll conducted by the Warsaw University Center for Research on Prejudice, researchers concluded that more than half of Polish youth visit anti-Semitic websites that glorify Hitler and Nazism. In Hungary, Marton Gyongyosi, an MP for the far-right Jobbik, who is the vice-chairman of the Parliament’s Foreign Affairs Committee, had called for the authorities to compile a national list of Hungarian Jews, especially those in parliament and government, who represent what he described as a “national-security risk”, allegedly slanting Hungarian foreign policy in Israel’s interest.

In general, it should be noted that hate speech against the abovementioned groups, but also others, is very common in Central Europe and it seems more tolerated by the members of Central European societies. Therefore, it must be combated. Most former communist states in Central Europe regulated hate speech on the basis of its content. Some of the post-Soviet states, like Lithuania or Estonia, the post-Yugoslav republics and Romania, incorporated the anti-hate speech provisions into their constitutions. It is important to notice that the constitutional regulations of hate speech emerged in the region in states with big national minorities and heavy tensions between the groups of citizens (or non-citizens).

The scope of laws in different countries varies. Some states regulated hate speech with very general terms, giving their law enforcement bodies more freedom, while some have detailed regulations.

Combating hate speech

Hate speech can interfere with human rights and also with so-called operative values, such as dignity, non-discrimination, equality, freedom of expression, religion, association or effective participation in public life. Additionally, hate speech harms individuals and causes damages in individuals such as psychological damages, fear, inhibited self-fulfillment or disintegrated self-esteem. And this is the reason why it should be fought with legal instruments.

Such fight is as at least as old as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, that reads: “Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers”. Also in the European Charter of Human Rights we read in Art. 11: “Everyone has the right to freedom of expression. This right shall include freedom to hold opinions, and to receive and impart information and ideas without interference by public authority and regardless of frontiers. This article shall not prevent States from requiring the licensing of broadcasting, television or cinema enterprises.”

The first hate speech legislation in European nations in the 20th century was aimed at stopping political racism associated with fascism and the experiences of the World War II. After the war, the United Nations, through various declarations and treaties, sought to fight racist regimes. In its International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (IECRD) the UN linked racial discrimination with racism, in an effort to outlaw not only discriminatory treatment but also hate speech and other elements of racism that might not fall under the definition of racial discrimination.

There is already quite a long list of legal instruments that are supposed to restrict hate speech from the public space. A very special place in that system of protection hold the Council of Europe (CoE) and the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR). Both were created to guard legal standards, human rights and democracy. Among those international legal instruments are:

-

The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (e.g.. Article III(c) – direct and public incitement to commit genocide);

-

The International Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD) (esp. articles 4 and 5 – all dissemination of ideas based on racial superiority or racial hatred, incitement to racial discrimination, with due regard to the right to freedom of expression);

-

The International Convention on Civil and Political Right (ICCPR) (esp. Articles 19 and 20 – respectively, freedom of expression and advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence).

Many of the treaty provisions have been clarified by General Comments or Recommendations, eg. Human Rights Committee’s General Comment No. 34 on the right to freedom of expression and the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination’s General Reccommendation No. 35, entitled “Combating racist hate speech”. ICERD is of special interest because it contains provisions on the relationship between freedom of expression and hate speech. Article 4 thereof requires states to render several types of expression punishable by law. This makes ICERD a special tool that creates more far-reaching obligations for states than other treaties.

States Parties condemn all propaganda and all organizations which are based on ideas or theories of superiority of one race or group of persons of one colour or ethnic origin, or which attempt to justify or promote racial hatred and discrimination in any form, and undertake to adopt immediate and positive measures designed to eradicate all incitement to, or acts of, such discrimination.

In Europe, Article 10 of the European Convention of Human Rights (ECtHR) is the centerpiece for the right of freedom expression. It reads as follows:

1. Everyone has the right to freedom of expression. This right shall include freedom to hold opinions, and to receive and impart information and ideas without interference by public authority and regardless of frontiers. This article shall not prevent States from requiring the licensing of broadcasting, television or cinema enterprises.

2. The exercise of these freedoms, since it carries with it duties and responsibilities, may be subject to such formalities, conditions, restrictions or penalties as are prescribed by law and are necessary in a democratic society, in the interests of national security, territorial integrity or public safety, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, for the protection of the reputation or rights of others, for preventing the disclosure of information received in confidence, or for maintaining the authority and impartiality of the judiciary.

In 1996 the European Union also adopted a Joint Action that encouraged action from Member States to prevent perpetrators of racist acts from moving to States with more lenient laws by either criminalizing certain behaviors, or by agreeing to remove the requirement for double criminality. On 28 November 2008, the Council of the EU adopted the Framework Decision on combating certain forms and expressions of racism and xenophobia by means of criminal law. As regards hate speech, Member States must ensure that the following intentional conduct is punishable when directed against a group of persons or a member of such a group defined by reference to race, color, religion, descent or national or ethnic origin:

– public incitation to violence or hatred, including by public dissemination or distribution of tracts, pictures or other material;

– public condoning, denying or grossly trivializing

– crimes of genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes as defined in Articles 6, 7 and 8 of the Statute of the International Criminal Court (hereinafter ‘ICC’); or

– the crimes defined in Article 6 of the Charter of the International Military Tribunal appended to the London Agreement of 8 August 1945, when the conduct is carried out in a manner likely to incite violence, or hatred against such a group or one or more of its members.

Poland

Hate speech in Poland is, of course, very often connected with the most radical organized groups. The extremist nationalistic groups are: Narodowe Odrodzenie Polski (National Rebirth of Poland), Obóz Narodowo–Radykalny (ONR; National-Radical Camp) and Stowarzyszenie Narodowe Zadruga (National Association Zadruga). They have all organized different kinds of events, like marches, concerts, happenings, where they chant and shout radical, nationalistic, xenophobic slogans, e.g. “Our sacred Res – Jews from Poland go away”, “Whole Poland – only white”, “Free Poland – no niggers”. What is more, the ONR delegates “greeted” the memorial of Silesian insurgent with Nazi gesture.

However, it would be naive to think that hate speech in Poland is produced only by the marginalized extremists. It is also used by others, especially by the politicians, what is definitely worrying. Otwarta Rzeczpospolita (Open Republic), an association that, among others, monitors hate speech activities in Poland, gives an example of Maciej Giertych, a member of the European Parliament and the father of the deputy-prime minister in the Kaczynski government, who published a brochure “The War of Civilizations in Europe”. The publication referred to the works of a conservative historian Feliks Koneczny and presented Jews in a way that could lead to aggression and dislike as a “worse” nation. It is important to underline that Hans-Gert Pöttering called the brochure “the substantial violation of the fundamental individual rights, especially the right to dignity of a human being”10

Polish political scene has been sharply divided between the ruling Platforma Obywatelska (PO; Civic Platform) and the conservative Prawo i Sprawedliwość (PiS; Law and Justice). This conflict is not really about the political agenda but it is personal and powered by the attitude towards the Smolensk tragedy (when Lech Kaczynski died in the plane crash in Russia). Both sides of the camp speak about the other side without any respect, using words that can often be recognized as hate speech. Political aggression has been growing in years. Escalation of hate speech in Polish political discourse was noted after last elections when the first openly gay deputy and first trans-gender deputy won seats in the Polish parliament. This negative attitude towards sexual minorities has been strengthened by the Catholic Church and its crusade against “gender ideology”.

The example is set by the people at the top. An average Joe Bloggs speaks the way elites do. Hate speech is more and more acceptable in everyday situations. It is used in private conversations, written on walls, can be read in media and is omnipresent in the Internet. To sum up, hate speech in Poland is not a marginalized matter of the extreme right, it is observed in all groups, from the football hooligans to members of academia.

In the 2014 report on hate speech in Poland we read:

„I detest fags – they are degenerate human beings, they should be treated” – every fifth Pole thinks that such a statement is admissible in the public discourse. Almost two thirds of young Poles encountered examples of anti-Semitic hate speech on the Internet. About the same percentage of Polish young people heard hate speech towards Romani people from their friends. Every third adult Pole has read racist statements on the Internet, and as much as 70 percent of young Poles declare that they encountered such statements on the Internet. Surprisingly high percentage of Poles accept hate speech – in particular towards Jews, Romani people, and non-heterosexual persons – and see nothing offensive in it. But the representatives of the minorities are affirmative that such statements are offensive and should be forbidden.

These are the results of the latest study performed by the Warsaw University Centre for Research on Prejudice and the Stefan Batory Foundation11.

The survey showed that hate speech against non-heterosexual people receives the highest acceptance in Poland. 35% of adult and 38% of young Poles perceive it as acceptable. The most offensive statements were seen as acceptable by 22% of adult Poles and 20% of young people. Only 59% of adults said that such statements should be forbidden. Homophobic hate speech is encountered by young people mainly on the Internet (77%), when talking with friends (65%), and on the TV (33%). The level of acceptance for anti-Muslim hate speech is also relatively high – 15% of adult Poles and 19% of young people think that the statement: “Muslims are stinky cowards, they can only murder women, children and innocent people” is admissible.

Surveyed Poles (both adults and young people) believe hate speech towards Ukrainians and Africans/black people to be forbidden, but they are willing to accept hate speech against LGBT people, Romani people and Jews. The acceptance of hate speech, especially among young people, is strongly related to their right-wing, hierarchical attitudes. People with right-wing views were in particular tolerant of hate speech towards non-heterosexual people12.

Anti-hate speech laws in Poland

Hate speech laws in Poland are regulated at the constitutional level. Article 54 of the Constitution protects freedom of speech. By its Article 13, the Constitution prohibits political parties and other organizations which have programs based upon totalitarian methods and the modes of activity of Nazism, fascism and communism. Article 13 further prohibits any programs or activities which promote racial or national hatred. Article 35 gives national and ethnic minorities the right to establish educational and cultural institutions and institutions designed to protect religious identity.

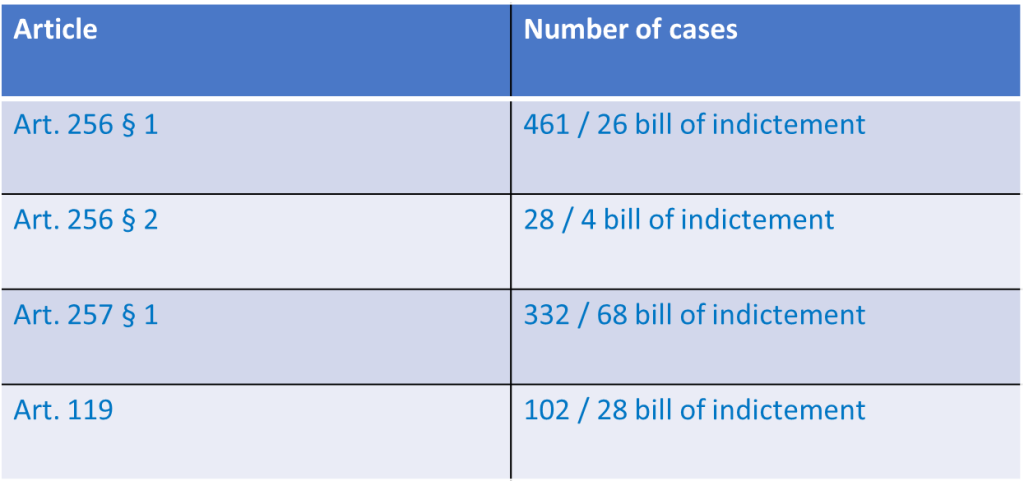

Additionally, hate speech is regulated in criminal code: Article 196 makes anyone found guilty of intentionally offending religious feelings through public calumny of an object or place of worship liable to a fine, a restriction of liberty, or to imprisonment for a maximum of two years. Article 256 makes anyone found guilty of promoting a fascist or other totalitarian system of state or of inciting hatred based on national, ethnic, racial, or religious differences, or for reason of the lack of any religious denomination, liable to a fine, a restriction of liberty, or to imprisonment for a maximum of two years. Article 257 makes anyone found guilty of publicly insulting a group or a particular person because of national, ethnic, racial, or religious affiliation or because of the lack of any religious denomination liable to a fine, a restriction of liberty, or to imprisonment for a maximum of three years.

Additionally, Article 119 makes anyone found guilty of using violence or threats against a person or group of persons due to their nationality, ethnicity, race, political convictions, and religion up to 5 years of imprisonment.

Nevertheless, the statistics showing the number of people punished for committing hate crimes are very low.

There are many reasons why these articles are not used frequently by the police and the prosecution, among them:

-

Considered as low priority by prosecution authorities

-

No specialists to combat internet-related issues

-

Social acceptance of discriminatory speech (language issue)

-

Limited scope of legal regulations (sexual orientation, political convictions)

-

At local level prosecutors friends with perpetrators

-

No reaction from society

-

Little engagement of Internet Intermediaries/Internet Service Providers

All these reasons are intertwined. The society continues to be passive and does not see hate speech and hate crimes as important issues to be combated by the state authorities. This is transplanted onto the state organs. The definition of hate speech is not broad enough. The law-givers have not covered some important parts of hate speech, like gender-based hate speech, since there is not much public support for penalizing this kind of speech.

Moreover, the police and the prosecution do not treat these kinds of crimes with priority and victims are often convinced about the insignificance of their case. Another issue is connected with the fact that lots of hate speech crimes “take place” online and the police is not trained properly and does not have enough man power to take account of all the online hate speech cases.

On the other hand, some hate speech cases become very famous since they bring lots of media attention. It is connected with the fact that hate speech is a very delicate part of the legal system, and this involves regulating sensitive matters that interfere in the sphere of private feelings and sentiments. What is more, it often happens that they involve famous people or celebrities who are infamous for their controversial behavior. For example in 2010, the police charged the Polish singer Doda (Dorota Rabczewska) with violating the Criminal Code for saying in 2009 that the Bible was “unbelievable” and written by people “drunk on wine and smoking some kind of herbs”. The same year, the police charged the lead singer and guitarist of the Polish death metal band Behemoth, Adam Darski, with violating the Criminal Code. The charge dated back to a performance by Behemoth in September 2007 during which Darski allegedly called the Catholic Church “the most murderous cult on the planet”, and he tore up a copy of the Bible on stage. In 2006, the Jan Karski Association complained that a broadcast on a catholic radio station defamed the Jewish people and violated Article 257 of the Criminal Code. Prosecutors refused to pursue the matter.

How to change the current situation

Projekt: Polska and the European Liberal Forum prepared a policy paper entitled “Liberal Agenda Against Online Hate Speech”.13 It focuses mainly on hate speech in the Internet, but contains also more general recommendations. Among others, these policy recommendations are:

-

Broadening the scope of the definition of hate speech;

-

Ratification of the Additional Protocol of the Convention on Cybercrime;

-

Better monitoring of implementation of Framework Decision on combating certain forms and expressions of racism and xenophobia by means of criminal law;

-

Fast implementation of the Victims’ Directive;

-

Introducing online filtering capacities;

-

Online filtering capacities situated in the region.

These recommendations can improve the situation in Central Europe. Of course, because of the specific situation in the region some of them must be tailored to the needs of the particular countries. Education and integration is also a milestone to be achieved in combating hate speech in the region. Groups that are targeted by haters are very often alienated from big parts of the society. The hatred is connected with stereotypes and lack of knowledge about the groups. Therefore, campaigns that will bring closer Romanis, LGBT people or Jewish communities to other citizens can help more than any legislation. Educational campaigns for the youngest audience are of the utmost importance.

Projekt: Polska has been fighting hate speech for many years with its HejtStop project. HejtStop project aims at removing hate speech from the public space in Polish cities. A special web site was created, wherein everyone could send a picture of an offensive graffiti, and the coordinators together with local authorities, owners of the walls, and with the support of private companies, removed them. Some were covered with beautiful murals. The project received large success initially and developed further. A special application and HejtStop remove hate speech from social media. The campaign is a perfect example of a good practice that shows how we can fight hate speech successfully. We hope that similar campaigns will spread across Central Europe soon, with the help of other liberal organizations.

An article by Miłosz Hodun from Projekt: Polska.

The article was originally published in the second issue of “4liberty.eu Review” entitled “Energy: The Challenges Europe Must Face”. The magazine was published by Fundacja Industrial in cooperation with Friedrich Naumann Stiftung and with the support by Visegrad Fund.

Read the full issue online.

1The Council of Europe against online hate speech: Conundrums and challenges.

2 http://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/hate_speech_warsaw_slide.pdf

3András Sajó, Freedom of Expression (Institute of Public Affairs, Warsaw 2004) p. 128.

4Stewart 2012, European Union Monorities and Discrimination Survey

5Goldstone 2002, 156

6Daroczi 2012

7More http://ecpr.eu/Filestore/PaperProposal/c6f365c3-025d-41e3-809d-172390f5ba9e.pdf

8It is important to note that the Czech Republic comes last in the whole survey (only 2%).

9http://fra.europa.eu/en/publications-and-resources/data-and-maps/survey-data-explorer-lgbt-survey-2012

10http://www.aedh.eu/plugins/fckeditor/userfiles/file/Discriminations%20et%20droits%20des%20minorit%C3%A9s/Hate%20speech.pdf

11Michał Bilewicz, Marta Marchlewska, Wiktor Soral, Mikołaj Winiewski Warsaw, 2014

12Ibid.

13Available here: http://www.liberalforum.eu/en/publications.html