The Republikon Institute has recently conducted its monthly public opinion poll for the second time. The survey was conducted in days both preceding and succeeding the Brussels attacks, on a sample representative from the aspects of gender, age, level of education and type of settlement. Beside party preference, we also asked the voters about their opinion on certain important policy issues. In March, we inquired in the additional questions about the referendum on the immigration quota initiated by the government, as well as the situation of the public education.

We measure party preference based on the answers of voters with declared party preference; those are the ones who are able and willing to name a party as a response to this survey. This category is of adequate subsample size and provides a fair approximation of real party preferences between two elections, as in such periods expressed willingness to vote is of less importance.

Beyond party preferences we also measured the desire to change a government, a preference that goes beyond supporting certain parties. We asked respondents what composition of government would they prefer after the next elections. When casting a ballot, a voter does not only express her partisan preference, but also wants to decide on the composition of the upcoming government. On the level of voters, this is not completely in line with the preferences of politicians of the given parties.

-

Among decided voters, Fidesz still holds a substantial advantage.

-

Given that Jobbik keeps weakening, currently MSZP is the strongest party of the opposition.

-

The Fidesz-KDNP alliance somewhat strengthened, while the number of undecided voters decreased.

-

Ongoing protests focusing on the situation of the public education did not change the popularity of the traditional left-wing parties nor could they increase support for the smaller leftist parties with a more civic image.

-

Electoral blocks are divided, both on assessing the situation of public education and on the issue of the proposed referendum about the immigration quota.

Results1

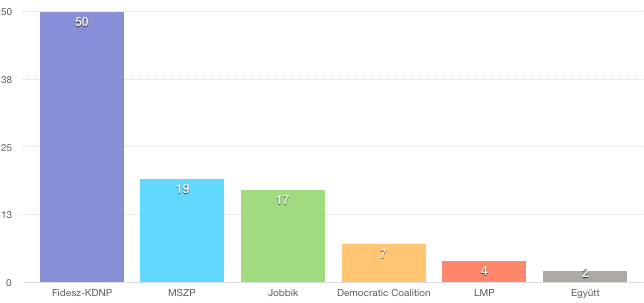

Among those who were able and willing to name a party of their preference, the Fidesz-KNDP alliance was supported by 50 per cent of voters in March 2016. The party with the second best standing is MSZP with 19 per cent of expressed support. Compared to February, Jobbik lost 5 percentage points resulting in losing its second place and currently being third with the support of 17 per cent of voters. The Democratic Coalition (DK) gained 3 percentage points since the last month, now being preferred by 7 per cent of decided voters. LMP is still around the parliamentary threshold with 4 per cent and Együtt claims the support of 2 per cent. No measurable change was recorded in the case of these two latter parties since February.

Figure 1: Party preferences of decided voters

One possible explanation for the changes occurring in the last month might be the terrorist attack in Brussels, as our survey was conducted around the time of this event. This is signaled by the strengthening of Fidesz and the weakening of Jobbik, as the latter party cannot overbid the anti-refugee attitudes generated by the government. The data presented below on the proposed referendum of immigration quotas also suggest that this issue might be especially favorable to the Fidesz.

One possible explanation for the changes occurring in the last month might be the terrorist attack in Brussels, as our survey was conducted around the time of this event. This is signaled by the strengthening of Fidesz and the weakening of Jobbik, as the latter party cannot overbid the anti-refugee attitudes generated by the government. The data presented below on the proposed referendum of immigration quotas also suggest that this issue might be especially favorable to the Fidesz.

According to the data gathered in March, the MSZP is the strongest party of the opposition and the popularity of the Democratic Coalition has also grown. Favorability ratings for the two parties with the most civic image, LMP and Együtt, however, did not increase despite the teachers’ protests. Thus it seems that the events unfolding in connection with the public education do not have direct consequences to party preferences (as opposed to the Brussels attacks), and that not even parties with a stronger civic background can gain popularity from protests that are otherwise not directly partisan in their nature.

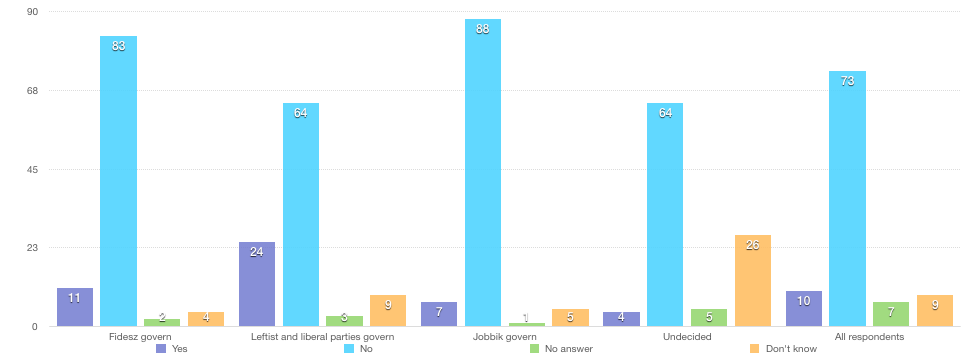

Figure 2: Assessment of the quota referendum (‘Do you want the European Union to prescribe the mandatory settlement of non-Hungarian citizens in Hungary even without the consent of Parliament? ‘) Percentages of those who agree with the specific statement, grouped according to the preferred government after 2018

Responses given to policy questions show that the electoral blocks are divided on the issue of the proposed referendum about the immigration quota or when it comes to assess the situation of public education. 70 per cent of respondents indicated that they would ‘definitely or likely’ go to the referendum initiated by the government. Turnout rates in past referenda in Hungary were way below this number. Nonetheless, one cannot foresee precisely the turnout rates of referenda. Willingness to participate is usually overestimated by pollsters, as it is easier to indicate such intentions in a survey situation than to actually show up at the ballot boxes. This is especially true in the case of referenda.

Responses given to policy questions show that the electoral blocks are divided on the issue of the proposed referendum about the immigration quota or when it comes to assess the situation of public education. 70 per cent of respondents indicated that they would ‘definitely or likely’ go to the referendum initiated by the government. Turnout rates in past referenda in Hungary were way below this number. Nonetheless, one cannot foresee precisely the turnout rates of referenda. Willingness to participate is usually overestimated by pollsters, as it is easier to indicate such intentions in a survey situation than to actually show up at the ballot boxes. This is especially true in the case of referenda.

Those who would prefer either Fidesz or Jobbik as the governing party clearly support the stance of the government in connection with the immigration quota. Even the majority of non-pro-governmental and non-Jobbik voters would oppose the quota on a referendum. According to our data, 73 per cent of all respondents share this view; from this mean value, pro-governmental and left-liberal voters diverge with 10-10 percentage points. This suggests that preferences on the government influence the assessment of quota referendum only to a limited extent.

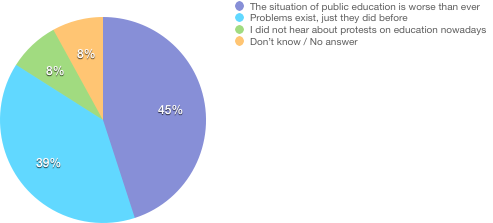

While on the issue of the quota referendum the governmental side has the lead, when it comes to questions of public education, the anti-governmental attitudes prevail. The plurality of interviewed (45 per cent) believes that public education is in a worse state than it has ever been. Only 39 per cent of voters believed that problems are comparable to the ones that existed before. The majority of those in our sample clearly know about the ongoing situation of the public education: only 8 per cent of them did not hear about the recent protests at all, showing the significance of the issue.

Figure 3: ‘What do you think about the protests on education?’

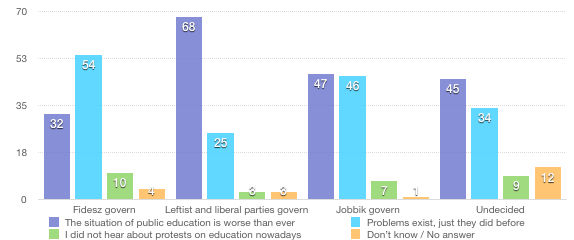

Figure 4: ‘What do you think about the protests on education?’ Percentages of those who agree with the specific statement, grouped according to the preferred government after 2018

Figure 4: ‘What do you think about the protests on education?’ Percentages of those who agree with the specific statement, grouped according to the preferred government after 2018

Preferences for and against the government, however, largely dominate the question of public education. 54 per cent of voters who would like to see Fidesz staying in government believe that the existence of problems in the public education is nothing new – this, of course, does not mean that they would be satisfied with the current situation. As opposed to this, 68 per cent of the leftist and liberal supporters share the view that the public education is at its worst state ever. Those who would like to see a Jobbik-government are divided on this issue, and nearly the same share of such voters side with one of the juxtaposed opinions. Those who have no clear preference on the future government, however, tend to be more likely to be dissatisfied with the situation of public education.

Preferences for and against the government, however, largely dominate the question of public education. 54 per cent of voters who would like to see Fidesz staying in government believe that the existence of problems in the public education is nothing new – this, of course, does not mean that they would be satisfied with the current situation. As opposed to this, 68 per cent of the leftist and liberal supporters share the view that the public education is at its worst state ever. Those who would like to see a Jobbik-government are divided on this issue, and nearly the same share of such voters side with one of the juxtaposed opinions. Those who have no clear preference on the future government, however, tend to be more likely to be dissatisfied with the situation of public education.

-

1 The study is based on a survey with a sample of 1000 respondents, interviewed personally and it is representative to Hungary from the aspects of gender, age, level of education and type of settlement.