In February 2024, Hungarian public life, previously marked by apathy, underwent a dramatic shift. A political scandal that reached the highest levels of government awakened Hungarian society. This rapid change reshaped Hungary’s political landscape within a few months and significantly shifted voter preferences. The party system was not spared from this rapid transformation either, and it can be clearly illustrated through Sartori’s party typology.

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the evolution of the Hungarian party system from the regime change to the present events.

Sartori’s Party System Typology

Italian political scientist Giovanni Sartori published his book Parties and Party Systems: A Framework for Analysis in 1976. His analytical framework defines several criteria that allow researchers to categorize political party systems. For the Hungarian system, three models are particularly relevant:

- Moderately pluralist party system: This form typically emerges in democracies where 3–5 relevant parties operate and it may also occur in polarized systems. Its key features are:

- Absence or marginal influence of anti-system parties;

- Neither the government nor the system faces bilateral opposition;

- Political competition is bipolar, including large centrist parties aligning with one of the dominant blocs;

- Consensus among actors on basic constitutional values;

- Centripetal competition;

- Small ideological distance between relevant parties;

- Competing coalition alternatives with parliamentary turnover;

- A responsible opposition avoids making unrealistic promises, recognizing a genuine chance of governing..

- Two-party of two-bloc system: Although often idealized, pure two-party systems are rare. According to Sartori, strictly speaking, no country perfectly fits the model. It features:

- Two relevant parties capable of governing independently, competing for absolute majorities;

- Third parties may exist but cannot hinder governance (usually regional);

- The opposition has a realistic chance of gaining power, even if one party dominates several electoral cycles;

- Centripetal and moderate competition, no room for extremes;

- Consensus-oriented, small ideological distances.

Forms of Hungarian Party System Since the Regime Change

In the 1990 democratic elections, six parties entered Parliament. MDF (The Hungarian Democratic Forum; a conservative-nationalist party) won 42.5% of mandates; SZDSZ (Free Democrats Alliance; one of the two main liberal parties at the time) came second with 23.83%. Although MDF had previously cooperated with MSZP (Hungarian Socialist Party; the communist successor party, still an active political player) during roundtable talks, after the elections, they formed a coalition not with MSZP, but with FKGP (Independent Smallholder’s Party; the historical agrarian party) and KDNP (Christian Democratic People’s Party; a historical right wing party today is considered the satellite party of Fidesz).

This cooperation and the formation of a Christian-conservative political group divided the political spectrum into three camps. Fidesz (Young Democrats Alliance; a liberal party at the time) and SZDSZ, still close at the time, formed a liberal, anti-communist bloc. MSZP, due to its past, was largely rejected. According to Sartori, this structure fit best within a moderately pluralist model, with no significant anti-system parties yet, MIÉP (Hungarian Justice and Life Party; a far-right party) was founded in 1993.

In the 1994 elections, six parties again entered Parliament. MSZP won a landslide victory with 54.15% of mandates. Although it had an absolute majority, they governed with SZDSZ to enhance legitimacy and avoid tension. Their alliance marked the beginning of the collapse of the previous liberal-conservative-post communist balance. Many expected Fidesz and SZDSZ to form a liberal bloc, but instead, Fidesz shifted right to fill a power vacuum. The party system began evolving toward a two-bloc system, driven partly by the electoral system rewarding larger unified blocs. Still, the system fit Sartori’s moderate pluralism.

In 2002, the two-bloc structure became clearer. Only three lists entered Parliament: Fidesz-MDF, MSZP, and SZDSZ. Although the Fidesz-MDF alliance won more mandates, the MSZP-SZDSZ coalition formed the government by a margin of only five seats. Campaign rhetoric intensified ideological divides. A notable example was László Kövér’s infamous “rope speech,” which MSZP used in its campaign.

Controversy also arose around the Orbán-Năstase pact, which would have allowed all Romanian citizens (not just ethnic Hungarians) to work and access healthcare in Hungary. MSZP and SZDSZ criticized this and leftist philosopher Gáspár Miklós Tamás denounced the left-wing’s use of demagogic and xenophobic rhetoric to win.

In 2006, MSZP won again, this time without SZDSZ. With 48.19%, and SZDSZ’s 4.66%, it was the first time a party was re-elected in post-communist Hungary. This result may be attributed to Prime Minister Ferenc Gyurcsány’s new political style and his “100 steps” program. Viktor Orbán’s performance during the debate was less effective, while Gyurcsány’s use of concrete arguments proved more convincing.

Since the 2000s, both political camps no longer saw the other as legitimate. Gyurcsány’s emergence in 2004 deepened this polarization. Charismatic leaders dominated their parties and mobilized support through confrontational styles and polarizing rhetoric. According to political scientist András Körösényi, the era of democratic consolidation ended in autumn 2006, marked by the leaked Őszöd speech. The government’s legitimacy collapsed, public trust eroded, and voter preferences shifted right. The two-bloc system broke down, ending the alteration of power. [5]

In 2010, as expected, Fidesz won in a landslide with 67.88% of mandates (262 seats), achieving a constitutional majority. A new political system was intentionally created by Orbán and the Fidesz elite, interpreting their victory as a “revolution in the voting booth” and the birth of a new social contract— “the System of National Cooperation.” The far-right Jobbik and green LMP entered Parliament but rejected the left-right binary, with LMP leaning more toward the left.

In Kötcse speech in 2009, Orbán envisioned a central field of power, with a dominant party flanked by smaller opposition. Unlike the earlier consensus-based tripolar system (liberal/left/national), this central power aimed to transcend left-right divisions. Körösényi described Orbán’s politics as pragmatic but ideological and flexible—not fitting any academic framework (e.g., neo-Keynesianism). Populism plays a key ideological role. The identity of the enemy elite has shifted—from communist remnants to multinational corporations and EU bureaucrats. Anti-pluralism and top-down governance reduce opposition cooperation. Under statism, the state seeks to reshape the economy.

Since 2010, the dominant party has won four elections, legitimizing the narrative that 2010 was more than just a government change. Despite the central power’s unity, ideological divides have sharpened, and the structure hasn’t remained continuous. Jobbik’s mainstreaming in 2018 reduced the three poles to two again, but Mi Hazánk’s (a new far right with ex Jobbik members) entry restored the tripolar condition. The dominant party’s survival depends on charismatic leadership. [5]

Table 1: Evolution of Hungary’s Party System up to 2010

| Party system after 1990 | The emerging party system in the 2000s | The party system as of 2010 | |

| Sartori typology | Moderately pluralist multi-party system | (Quasi) two-party system | Predominant party system |

| Ideological divisions | Left-right-liberal divide | Left-right opposition | “Centrist power space”, again a tri-polar political divide (left-, dominant party, right opposition) |

| Reasons for the emergence of regimes | The regime change paradigm of liberal democracy | The breakdown of the paradigm of regime change (not in line with citizens’ expectations) | The legitimacy of the left of the two-bloc system has been weakened |

The development of bloc politics and the rise of a dominant party were significantly influenced by Hungary’s electoral system. Since 1990, it has been a mixed system with both proportional and majoritarian elements. The 1989 XXXIV. electoral law used a three-channel, two-round mandate distribution. Though still majoritarian in nature, it included balancing mechanisms.

2013 XXXVI. law about the election procedure increased majoritarian aspects: voting now occurs in a single round for one candidate and one national list. Single-member districts became more significant, and excess votes now transfer to national lists. The voters are allowed to vote for individual Members of Parliament (MPs) and one national list in one round. The importance of individual representatives has increased significantly, hence the larger share of the seats allocated.

A single vote is sufficient for a candidate to win a constituency seat and any votes above this are counted as votes for the national list. List nomination requirements have increased (71 candidates in 14 counties), forcing opposition cooperation. Over the past 15 years, Fidesz-KDNP has reshaped the electoral system to its advantage, including redrawing districts and adjusting proportionality.

Political Scandal That Triggered Change

On February 2, 2024, Hungarian media published the first article about K. Endre, pardoned by the then-president. The scandal became known as the pardon/pedophilia scandal. Widespread dissatisfaction could not be channeled by the insignificant opposition.

On February 16, influencers and public figures organized a protest—later dubbed the “influencer protest.” Political scientist Dániel Mikecz described it as unprecedented: social media figures organized an offline political demonstration.

On February 11, one of Hungary’s top political YouTube channels published an interview with Péter Magyar, ex-husband of former Justice Minister Judit Varga, who exposed internal corruption in the Orbán system. On March 15, he announced the formation of a new party: Respect and Freedom Party (TISZA).

Transformation of the Party System

The TISZA Party grew significantly within a year. Since it has not yet a parliamentary election contested against the dominant party, the 2024 European Parliament elections are the best benchmark. The ruling Fidesz won 44.8% of the vote (11 of 21 Hungarian seats). TISZA came second with 29.6% (7 seats). Currently, only opinion polls are available as indicators for standing.

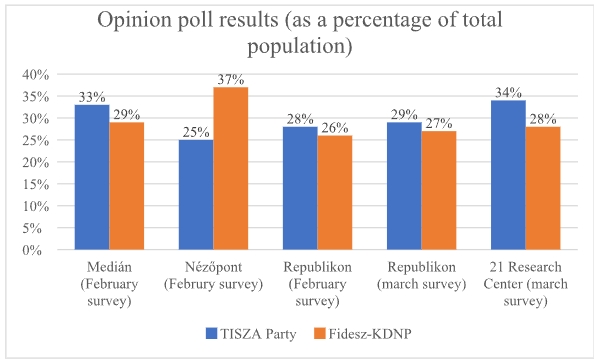

Results vary significantly by pollsters. A Median poll for HVG in March showed 46% of decided voters supported TISZA, 37% Fidesz-KDNP. In the general population: 33% TISZA, 29% Fidesz-KDNP. The pro-government Nézőpont Institute showed TISZA at 25%, Fidesz-KDNP at 37%. Republikon Institute (February) showed TISZA at 28%, Fidesz-KDNP at 26%. In March, both Republikon and 21 Research Center showed TISZA rising to 34% vs. Fidesz-KDNP at 28%, based on hybrid (phone + online) surveys.

Figure 1: Differences in Public Opinion Polls

Overall, while polling methods differ and may not provide certainty, trends are becoming clear: Fidesz is beginning to lose its dominant party status. In my view, Hungary’s party system is increasingly resembling Poland’s: a populist-conservative right versus a more progressive, liberal center-right bloc.

References:

[1] Enyedi, Zsolt; Körösényi, András (2001). Parties and party systems. Budapest – Osiris Osiris Publishing House, 2004. 151-161.

[2] Sartori, Giovanni (1976). Parties and party systems a framework for analysis. Oxford, Worcester College Oxford University – ECPR Press 2005. 164-204.

[3] Tóth, Csaba (2001). The main direction of the development of the Hungarian party system. Political Science Review. Vol. 10 No. 3. 81-104.

[4] The Hungarian Round Table Talks were a series of formalized, orderly and highly legalistic discussion held in the summer and autumn of 1989, inspired by the Polish model, that ended in the creation of a multi-party constitutional democracy.

[5] Körösényi, András (2015). The three stages of Hungarian democracy and the Orbán regime. In András Körösényi (ed.): The Hungarian political system after a quarter of a century. Budapest, MTA TK PTI – Osiris Publishing House 401-422.

[6] Soós, Gábor (2012). Two-block system in Hungary. In András Körösényi, Zsolt Boda (eds.): Is there a direction? Trends in Hungarian politics. Budapest MTA TK PTI – New Mandate Publishing House 14-40.

[7] On March 23, 2002, Fidesz held a campaign rally in the Youth Hall of Békéscsaba. László Kövér, then Vice President of Fidesz, argued for organizing the Olympic Games in Hungary in front of a crowd of 150. The recording of this speech leaked to the press before the general elections in 2002. The oppositional Socialist party built their campaign on several sentences from the speech, and they willingly misinterpret his message. (This willful misinterpretation was later acknowledged by Ferenc Gyurcsány.)

[8] Political Capital (2002). The Orbán-Nastese pact in the press. https://politicalcapital.hu/konyvtar.php?article_read=1&article_id=582

[9] Political Capital (2005). The Hundred Steps programme. https://politicalcapital.hu/konyvtar.php?article_read=1&article_id=1311

[10] On September 17, 2006, Hungarian State Radio published on its website the audio recording of the MSZP parliamentary group meeting held in Balatonőszöd on May 26. Ferenc Gyurcsány, in his speech in a closed circle, tried to make the faction aware of the need for change, to convince them to start and carry through the economic adjustments and reforms necessary to clean up the public finances, and he admitted this self-critically: the government had lied all through the past year and a half or two years – ‘we lied morning, night and day’ – had done nothing for four years, and the country’s potential had been far exceeded.

[11] Szigeti, Péter (2014). The transformation of the Hungarian electoral system – a comparative perspective. Law Journal. Vol. LXIX, No. 2.

[12] Tóth-Bíró, Marianna (2020). The government further restricts the conditions for national list building in elections. Telex. https://telex.hu/belfold/2020/11/24/14-megyeben-legalabb-71-egyeni-jelolt-kell-majd-az-orszagos-listaallitashoz-a-valasztason

[13] Free Europe (2022). The redrawing of constituencies could also favour the governing parties. https://www.szabadeuropa.hu/a/a-valasztokeruletek-atrajzolasa-is-a-kormanypartoknak-kedvezhet/31708449.html

[14] Balázs Cseke (2023). Half a year before the election, the rules were rewritten, and Fidesz voted for the proposal of Our Country. Telex. https://telex.hu/belfold/2023/12/12/onkormanyzati-valasztasi-torveny-modositasa-budapest-parlament-mi-hazank

[15] Kaufmann, Balázs (2024). Katalin Novák has pardoned the accomplice who covered up for the paedophile ex-director of the Bicske children’s home. 444. https://444.hu/2024/02/02/novak-katalin-kegyelmet-adott-a-bicskei-gyerekotthon-pedofil-exigazgatojat-fedezo-buntarsnak

[16] Péli-Koronkai, Gergely (2024). Friday’s demonstration in Heroes’ Square could have been a global innovation. Telex. https://telex.hu/techtud/2024/02/17/tuntetes-hosok-tere-budapest-online-tartalomgyartok-influenszerek-mozgalom

[17] National Election Office (2024). Results of the election of members of EP. https://vtr.valasztas.hu/ep2024

[18] Antal, Bálint (2025). Median: Tisza’s lead among the sure voters is 9 percentage points. Telex. https://telex.hu/belfold/2025/03/12/median-9-szazalekos-a-tisza-elonye

[19] Pártpreferencia.hu (2025). 2025 Q1 quarterly analysis. https://partpreferencia.hu/2025-q1-negyedeves-elemzes/

[20] Nézőpont Institute (2025). The Tisza has reached its peak. https://partpreferencia.hu/2025-q1-negyedeves-elemzes/

[21] Republikon Institute (2025). Tisza two percent ahead of Fidesz. https://republikon.hu/elemzesek,-kutatasok/250301-kkv.aspx

[22] Republikon Institute (2025). The power relations of January have returned. https://republikon.hu/elemzesek,-kutatasok/250409_kvk_marcius.aspx

[23] 24.hu (2025). 21 Research Centre:Tisza has hundreds of thousands more voters than Fidesz. https://24.hu/belfold/2025/04/10/21-kutatokozpont-tisza-part-fidesz-kozvelemeny-kutatas/