‘Liberation Day’ marked a real threat to the world, as it risked sparking a global trade war. On 2 April, Donald Trump announced the largest tariff hike since the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act, 1930. This move reflected Trump’s views on international trade and the global economy: He sees trade as a zero-sum game that the US is losing, and, to him, tariffs are a way to help the American economy and public finances.

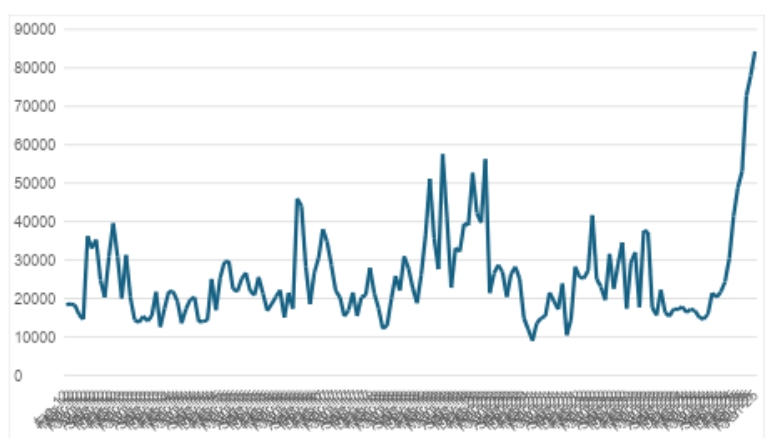

As economics shows, a decrease in economic openness and international trade leads to a global decrease in welfare (OECD 2025). Forecasts of economic growth have sharply declined while global uncertainty levels have increased – the World Uncertainty Index (Figure 1) has reached higher levels than during the Covid-19 pandemic (Ahir et al., 2022). This index is computed based on occurrence of word ‘uncertain’ in the Economist Intelligence Unit country reports – higher values mean higher uncertainty. In these circumstances, governments around the world were unsure how to respond to Trump’s tariffs – to retaliate or not to retaliate. In the case of powers like the EU, an added dilemma is whether to pose as a ‘real player’ in the global economy or focus on reducing harm for citizens.

Figure 1: World Uncertainty Index

Initially, the European response to Trump’s so-called ‘Liberation Day’ was based on a carrot-and-stick approach. On the one hand, European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen spoke of potential countermeasures – beginning with the steel sector, but not limited to it in the long run. On the other hand, the EU negotiated with the US administration to agree on a trade deal, with a ‘zero-for-zero’ approach.

This, unfortunately, received a negative reaction from US president Donald Trump, who opted for further escalation of the trade conflict by announcing his intention of imposing a universal tariff on all imports from the EU, capped at 50%. This was later averted thanks to a series of phone calls between European leaders and the US president, which resulted in the postponement of the imposition of these tariffs and paved the way for diplomacy.

In the meantime, the EU was bracing for the worst, preparing and adopting (though in a diluted form) next response packages potentially aimed at the ‘red states’ of the US. In addition, there were discussions on the potential use of the EU Anti-Coercion Instrument (ACI), initially adopted as a response to the trade ramifications of Trump’s first term. The ACI allows the EU to potentially restrict imports and exports from a targeted country, as well as to block companies incorporated in such a country from participating in public tenders.

There were also discussions about the European Commission instituting more rigid scrutiny of US digital giants under the Digital Markets Act (DMA) and Digital Services Act (DSA), which could have potentially led to infringement procedures against said companies. Ultimately, none of this has materialised, as the more dovish faction gained the upper hand, resulting in the current deal.

The Deal

The deal that was struck sets a unilateral tariff of 15% on most European exports to the US, with certain exceptions and no retaliation from the EU, which has opted for a 0% tariff rate on US-manufactured goods. The exceptions include aircraft and components, certain chemicals, certain generics, semiconductor equipment, certain agricultural products, natural resources, and critical raw materials – all of which will be exempt from tariffs on both sides.

However, the deal itself does not fundamentally change the standoff between the two sides with regard to the steel sector, as the only potential change would be an increase in tariff exemption quotas that are yet to be negotiated.

Another set of provisions in the deal includes the: intention to reduce non-tariff barriers (e.g., on car standards and phytosanitary measures) by both sides, an increase in cooperation on economic security (which would lead to stronger cooperation on investment screening and export controls as well), increased procurement by the EU of US liquified natural gas, oil, and nuclear energy products (valued at $750 billion, over the next three years), and the promotion of mutual investments, with EU companies investing at least $600 billion in the US by 2029.

In addition, the US has emphasised the EU’s intent to ‘purchase significant amounts of US military equipment’, though EU officials say the Commission has no power over arms procurement and cannot promise this.

Regardless of the aforementioned contents of the EU–US trade deal, however, we must remember that at this point, it is only an ‘agreement reached’ in purely political terms. It is not yet legally binding, as the details of multiple provisions have yet to be ironed out.

How Should We Perceive the Deal?

Now, while the announced agreement is only provisional at this point, a diversity of responses to it can be framed, depending on one’s priorities.

To begin with, there is the matter of saving face: The EU has definitely not achieved that goal. During the press conference at the Turnberry golf resort in Scotland, the European Commission president looked extremely weak compared to her host – President Trump definitely stole her thunder. The US president repeatedly interrupted his European interlocutor, with no reaction from Ursula von der Leyen. To make matters worse, the European Commission president repeated US statements about a need to mend ‘an imbalance, a surplus on our side, and a deficit on the US side’.

The entire situation is probably best summarised by the photo of both the EU and US delegations at the end of the press conference. The Americans are seen visibly gloating, whereas their European peers either wore forced smiles or were not smiling at all. This could come as no surprise. After all, it was a capitulation of the EU’s principled approach to world trade: The Commission decided to depart from WTO rules on trade agreements in order to secure a deal with the US, thus setting a dangerous precedent. One might add that such a profound move by the Commission resulted in nothing more than a trade agreement on par with the ones between the US and Japan or the US and South Korea (as imports from both countries will also face a tariff rate of 15% upon entering the US), not to mention the US–UK deal. This clearly shows that the Commission failed to leverage the bloc’s leading position in global trade.

However, there is a clear explanation for the EU trade delegation’s tactics. It revolves around the geopolitical situation of the EU, as well as its dependence on the US security guarantees. Both reasons can be seen in the statements by President von der Leyen and European trade commissioner Maroš Šefčovič, not to mention in the EU delegation’s approach to negotiations during the EU–China summit preceding the EU–US agreement. The Commission simply opted to safeguard transatlantic links and potentially secure a more favourable position on the Ukrainian question from the US , rather than focus on purely economic aspects.

Another reason for giving in to some of the US’ demands was the need to minimise the potential damage to trade relations between the two sides. As trade commissioner Šefčovič stated: ‘A trade war […] comes with serious consequences. With at least a 30-percent tariff, our transatlantic trade would effectively come to a halt, putting close to five million of jobs […] at risk.’

Although the deal shows the EU’s poor negotiating power and is widely considered a failure, it has some clear merits. Often, the agreement is compared to the a world without tariffs – an appealing vision, but for now, a utopian one. It should instead be compared to realistic options – such as the threat of 30% tariffs. With Donald Trump as POTUS, the return to a world without tariffs is only a dream. So, probably, a better deal was impossible to achieve.

Also, we should try to see the situation through Trump’s eyes: The US has a trade surplus with the UK, and yet that deal was concluded with a 10% tariff rate in the US’ favour. This shows who the real target of Trump’s trade policy is, and how he treats even countries that should not be considered a danger because of his protectionist views.

The EU’s humiliation, then, may be considered the cost of saving European consumers. The alternative to this deal was engaging in a trade war. Implementing retaliatory tariffs would involve costs that would have to be paid by EU consumers. Achieving a deal without imposing tariffs on US products imported into the EU is an example of sustaining choice and protecting lower prices for customers. The White House has precipitated a situation where tariffs are levied on the EU, but whose costs must be incurred by American consumers and importers. This not only increases costs for Americans, but it also distorts the US market by raising the prices of capital goods (Pomerleau and York 2025). In the long term, this protectionist trade policy will lead to a slump in investments and productivity in the US.

Moreover, this agreement can be considered as a way to reduce uncertainty for the EU, at least in the short term. For this deal to fully minimise uncertainty, however, it must be formally signed into a binding agreement. However, even achieving this political agreement is a move in the right direction – and now the EU’s economic agents know what they might expect in the future.

Credibility of the US and Donald Trump Himself

Ignoring all of the aforementioned optics of the EU–US agreement, it has one inherent flaw – namely, Donald Trump’s lack of credibility in the area of trade diplomacy, an issue that (by extension) applies to the US as a whole.

This issue emerged in the first Trump administration, with its decision to undermine the WTO system by blocking the appointment of new judges to its appellate body. That was a somewhat surprising move, given that it was the US that had been the main architect of the global rules-based trade order until that point. What is even more surprising is that the situation did not change much under the Biden administration, which has certainly impacted the US’ credibility as a partner in trade. And then, regardless of the US’ policy on the WTO, there is Trump himself.

As we have seen during his second tenure in office, Trump has a tendency to precipitately change his mind on the US’ approach to handling global issues (as seen in his attitude towards Ukraine and Russia). Given that the Turnberry deal is only of a political nature, it would be no surprise if Trump walks away from it or even presents new demands to the EU while threatening to move US troops out of Europe.

Such a risk is further deepened by the diverging interpretations of the US–Japan deal that have been presented by either side and the difference in the narratives around the promised EU investments into the US.

Finally, it seems more likely than not that the existing deal will remain even after Trump’s second term, as returning to a status quo ante or even a zero-for-zero deal would be hard for the US political establishment to sell its voters. This is best exemplified by the Joe Biden administration’s unwillingness to resolve the EU–US dispute over the steel sector (dating back to Trump’s first term), as well as its lack of interest in striking a free trade deal with the EU.

Remedies for Future

In order to safeguard its interests, the EU must develop a new ‘art of the deal’ – one based on the principles of free trade and a rules-based trade order – in a time of growing protectionism.

This change has to start within the EU itself. Regardless of the Commission’s lack of ability (or will) to leverage its global trade position during negotiations with the US, its international standing would be much stronger once the remaining intra-EU barriers to trade and capital are removed. Just the obstacles to the internal flow of goods are equivalent to a tariff rate of 44%, whereas those imposed on services are akin to a tariff of 110% (IMF 2024).

Then there is the yet-unresolved issue of uniting the capital markets of member states, which will greatly reinvigorate the European economy upon its completion (Philippe et al. 2025). To sum , the EU has to prioritise its integration with regards to the single market in order to facilitate its own growth – which in turn would strengthen its position in the global trade order.

However, the EU’s trade policy should not be limited to removing existing intra-EU barriers; the EU also needs to continue its proactive approach to fostering free trade agreements across the globe. Beyond the finalisation of the EU–Mercosur deal, the Commission should focus on strengthening trade links between the EU and other like-minded countries (for example, Australia), both in the form of new free trade agreements and adherence to the rules-based global trade order. The ultimate goal would be to create a block of states willing to conduct trade in a predictable and reliable environment, but not limited by it. Such a group should be able to present a unified front against the distortive actions of the US or China in global trade, in order to mitigate the damage to the world economy.

In these times of ‘slowbalization’, we need new trade agreements. We need them not just to increase the rate of economic growth, but also to be safe and important in international relations. As Tyler Cowen (2023) pointed out, autarky can be dangerous to the economy and society due to the lack of alternative supply chains. Therefore, the EU should seek out opportunities to create new supply chains and diversify imports, especially of critical materials. Moreover, at a time when the development of autocracies has accelerated, it is imperative that the EU find new allies. As some studies have pointed out (Kleinman et al. 2024; Tabellini and Magistretti 2025), trade can be a tool of political partnership too.

The last remedy is strongly connected to the previous one. The EU should not abandon WTO rules for global trade, but it must undertake reforms of this system, given that it has been deeply beneficial for member states. For years, the WTO managed to limit trade conflicts and arrest the damage resulting from them; it is essential to safeguard some form of it for the future.

References:

Ahir, H., Bloom, N., & Furceri, D. (2022). The World Uncertainty Index (Working Paper 29763). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w29763

Epicenter. (2025). Reviving Europe’s Competitive Edge. https://www.epicenternetwork.eu/publications/reviving-europes-competitive-edge/

IMF. (2024). Regional Economic Outlook for Europe, October 2024: A Recovery Short of Europe’s Full Potential. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/REO/EU/Issues/2024/10/24/regional-economic-outlook-Europe-october-2024

Kleinman, B., Liu, E., & Redding, S. J. (2024). International Friends and Enemies. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 16(4), 350–385. https://doi.org/10.1257/mac.20220223

OECD. (2025, March 17). OECD Economic Outlook, Interim Report March 2025. OECD. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/oecd-economic-outlook-interim-report-march-2025_89af4857-en.html

Pomerleau, K., & York, E. (2025, April 23). Understanding the Effects of Tariffs. American Enterprise Institute – AEI. https://www.aei.org/research-products/report/understanding-the-effects-of-tariffs/

Tabellini, M., & Magistretti, G. (2025). Economic Integration and the Transmission of Democracy. The Review of Economic Studies, 92(4), 2765–2792. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdae083

Written by Mateusz Michnik and Eryk Ziędalski.

Continue exploring:

[NEW RELEASE] Deregulation, Not Simplification: Blueprint for Europe’s Competitiveness