Marine le Pen and Nigele Farage victories in the European Elections won the titles of most newspapers around Europe. However, Slovakia managed to grab some headline space as well. Slovak voters’ turnout reach EU all time low record – again.

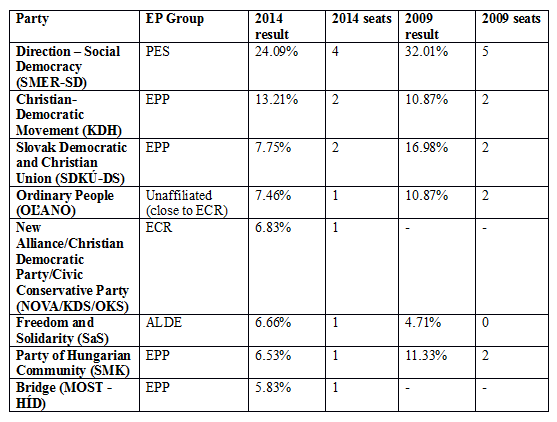

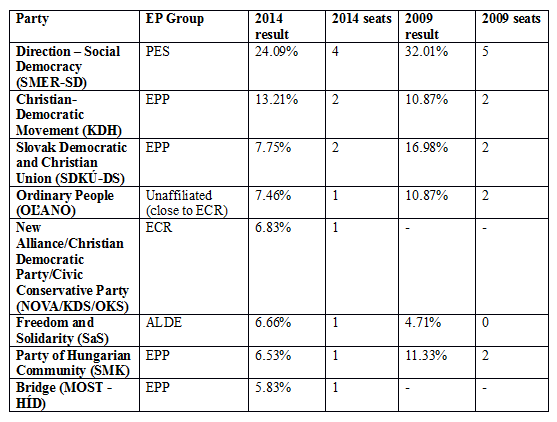

Only 13.05% of voters cared to cast a vote. The previous turnout was 19.64% in 2009 and 16.96% in 2004. Eight parties will share the 13 seats which Slovakia holds in the European Parliament.

The winner was the ruling social democratic party. However, the relative loss of votes (and one seat) is viewed as another blow to its popularity, after party’s leader and Slovak Prime Minister Robert Fico lost in presidential elections in late March. Its roster of MEP consists of EP veterans, including Maros Sefcovic, Commissioner for Inter-Institutional Relations and Administration, who is believed to return to his seat with another candidate taking his place in European Parliament.

Other elected MEPs are combination of veterans and new names. Five of the eight parties are strongly pro-European. Members of New Alliance/Christian Democratic Party/Civic Conservative Party parties occasionally present more reserved attitude towards EU-issues, can’t be considered euroscepticists though. The Ordinary People party presents rather homogenous pool of ideologies, with the elected MEP being strongly conservative. Freedom and Solidarity MEP, party leader Richard Sulik, has critique of EU as one of the main points on his agenda. However, unlike UKIP or Front National, his party promotes free market and personal freedom ideas instead of nationalism rhetoric. Shortly after elections, Mr. Sulik announced his consideration for leaving ALDE in search for more relevant alliance.

Despite recent shocking success in regional election, ultra-nationalists performed poorly, as did numerous extreme-left parties.

Several reasons for the low turnout are discussed. The pre-election campaign was mild and generally boring. INESS was the only organization to offer comprehensive review of party programs (and the results were cheerily used by the top candidates in TV discussions). However, most of the programs were trivial, lacking opinions on serious European issues (bailouts, federalization, tax/fiscal harmonization…). The ruling party even did not bother to publish any program until two weeks before the elections, few hours after INESS inquired for it at the party’s secretariat.

More deep-rooted reason is in local attitude towards the EU. European Union is viewed as a big brother – guarantor of certain local rule of law (most citizens still remember the authoritarian period of 1994-1998, when the country was a “black hole in the heart of Europe”) and open borders (there is little understanding of the difference between EU and Schengen). EU funds are welcomed, but viewed with growing suspicion due to the widespread corruption associated with them at the local level. Introduction of Euro was cheered and the common currency remains fairly popular, despite the slump caused by the sovereign debt crisis. Besides these topics, Slovak citizenry has no interest in European issues and Slovak politicians have not much intention of rising them, spending most of their years in Brussels invisible.

Being a member of the European club is sufficient for common citizen. European institutions and their processes are largely unknown to the voters and they feel no urge to show any opinion, when even the parties are largely ambivalent towards European issues.