There is a massive literature on globalization (see, e.g., Bordo 2017). Therefore, I limit my comments on this fundamentally important process to a bare minimum (sect. 1). Instead I focus on the criticisms of globalization. Sect. II distinguishes three points of view of this process: economic, political economy and moral. In sect. III I briefly discuss crude anti – globalism of the nationalistic and utopian variety. Then I move to more sophisticated versions of the discussions of globalizations focusing on what I perceive to be lack of clarity, misconceptions or outright fallacies. Sect. IV deals with trade globalization and sect. V – wi th financial globalization. In sect VI I formulate some final observations and recommendations.

I Globalization and Its Components

In the most general sense the process of globalization consists in increasing contacts (including contracts) among individuals’ and organizations from various countries. In this sense it is the opposite of isolationism. Economic globalization is reflected in the growing integration of markets (Bordo, 2017). In each period there is a level (state) of globalization as measured by various ratios, e.g. world exports to global GDP or the migrant population to the world population.

Globalization is usually divided into:

-

Trade globalization, i.e. trade in material products;

-

Financial globalization, i.e. flows of capital;

-

International migration.

One should add globalization of communication, i.e. increased flows of data which distinguishes modern globalization, with the invention of the telegraph, and later ICT technology, from the whole history of mankind until the 19th century. An interesting question is to what extent can this technology replace the face to face contacts between people from various places (Baldwin, 2016).

Another addition is the globalization of services, i.e. goods the production of which cannot be separated from their consumption. Therefore, the globalization of services has to be contained (until recently) in other flows:

-

Many services are contained in the goods which are moved across borders;

-

FDI, i.e. part of financial globalization, creates firms in foreign countries which offer services for business (e.g. consulting or accounting) or for consumers, e.g. McDonald’s;

-

Consumers of services move to foreign countries (international tourism);

-

Providers of certain services, e.g. construction workers move to another country for a certain time;

-

Modern improvements in ICT technologies enable the growth of tele-services, whereby a producer, e.g. a surgeon, performs the services at a distance. Therefore, ICT allows the spatial separation of production and consumption.

Finally, it is useful to see which components of globalization are most closely related to technology transfer, which is the most important driver in closing the gap between the less and more developed countries. Massive empirical research indicates that this role is played in particular by exports and imports of manufactured products, by the immigration of skilled people and by the FDI, as opposed to “pure” financial flows, especially those which finance increased government spending or the housing booms.

Therefore, in analyzing the growth prospects for the respective countries one should consider not only the overall scale but also composition of the globalization flows they receive. But remember that the scale and composition of those flows depend on the institutional systems and policies of the receiving countries

II Three Points of view on Globalization

1. Globalization is analyzed and assessed from three points of view:

-

economic;

-

political economy;

-

moral (ethical).

2. The economic analysis aims in general to explain the socio-economic outcomes, e.g. growth, stability, poverty, (un)employment, inequalities. This is also its main task with reference to globalization. Massive economic research has shown that trade isolationism, present in the socialist (non-market) economies and in the distorted, quasi-statist market economies, has been very costly in terms of foregone economic growth and thus lower standard of living of millions of people. (A.M. Taylor 1996, M. Wolff, 2004). One should remember that many professional economists had advocated socialism, i.e. the replacement of private ownership by the monopoly of the state ownership, and the replacement of the market by central planning (Balcerowicz, 1995). And it should not be forgotten that the statist doctrine of import substitution was until recently a part of mainstream economics, and it was supported by the World Bank (Wolf, 2004). The present discussion on the economics of trade globalization also often suffers from the lack of clarity, wrong assessments and sometimes wrong recommendations. I will come to this issue in sec. III, IV and V.

The political economy analysis aims at explaining political outcomes by linking them to various, less or more probable causes, including socio-economic outcomes. One should be very careful in drawing general conclusions from specific cases, e.g. from the present political backlash against trade globalization in the US under then candidate and now President Trump. I think that political outcomes are probably more difficult to explain than 4

economic ones because of a larger role of chance factors (including the appearance of special individuals’) in the former case than in the latter. Besides, even if one can convincingly link the anti-globalist political outcomes to import competition (and that is a big if – see later) there remains a basic question: what would be the policy recommendations?

The moral analysis should not be confused with moralizing. The moral analysis deals with the moral standards of judging various outcomes, including those that are – rightly or wrongly, linked to globalization. All too often economists, and even more, – other social scientists focus on the people whom they regard as globalization’s “losers” in the developed economies and disregard the beneficiaries of globalization in the poor countries (not to mention the winners in the developed states). Such a focus is a display of nationalistic ethics.

Universal ethics considers the consequences of globalization for all the groups in the world, and especially for the poor. And the gains for the latter group from the reforms which have opened the way to globalization have been huge.

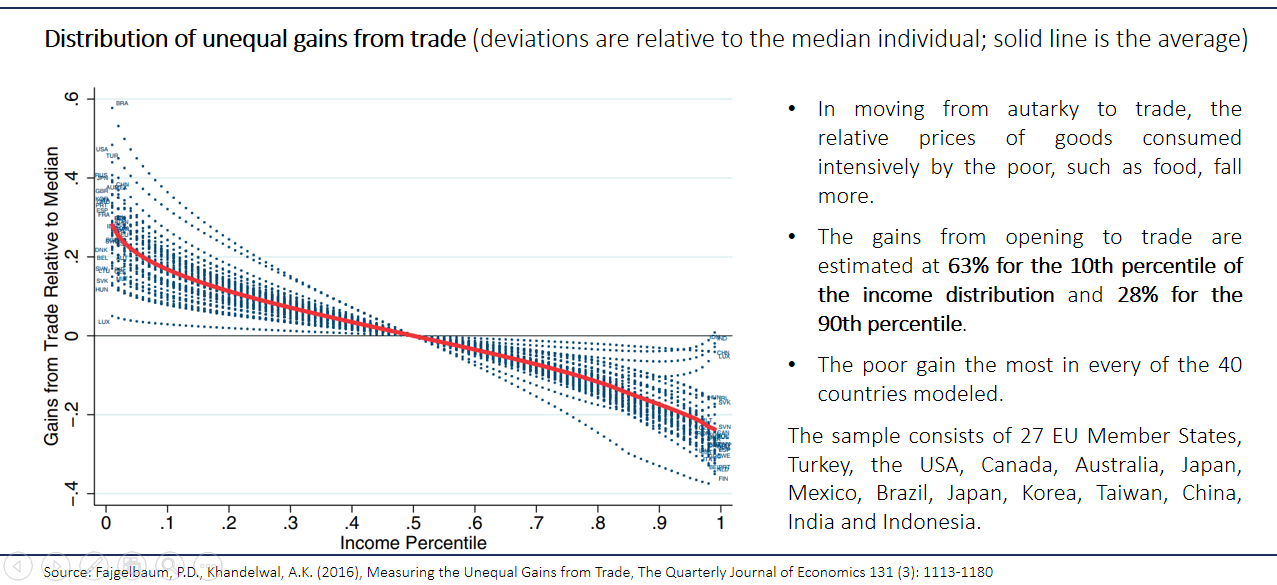

Figure 1. The poor gained the most from trade as their consumption patterns are focused on tradable goods, e.g. food and manufactured goods, and to lesser extent services. 5

Figure 1. The poor gained the most from trade as their consumption patterns are focused on tradable goods, e.g. food and manufactured goods, and to lesser extent services. 5

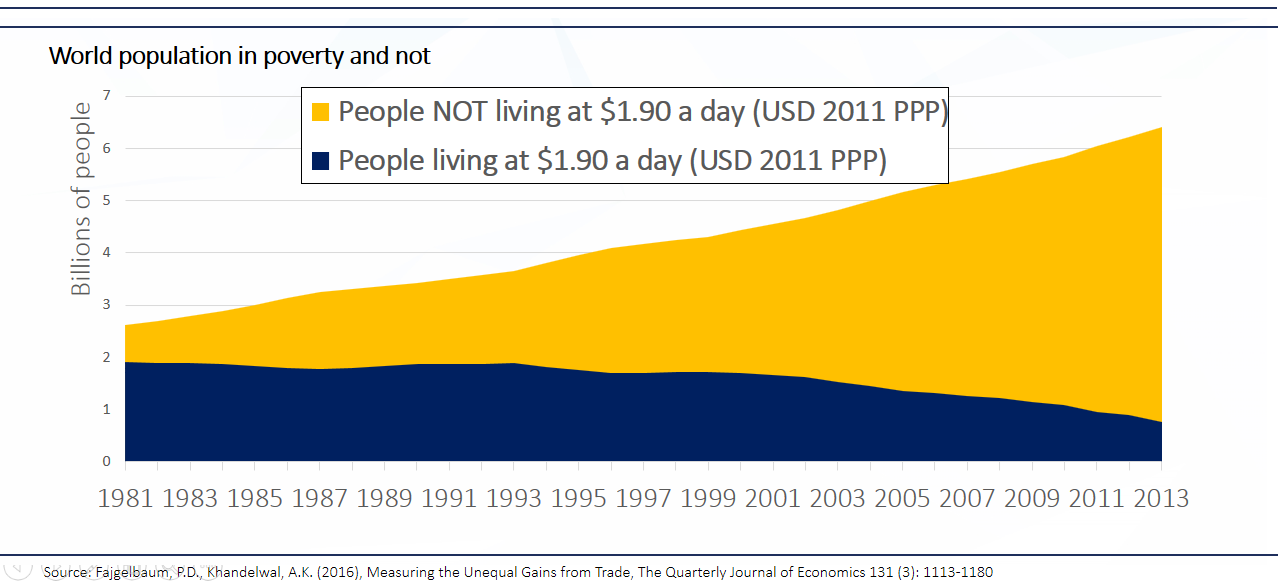

Figure 2. In 1981 42% of world population lived at $1.90 (2011 USD, PPP) and only 11% in 2013. This is despite the fact that world population increased during this time by 59%.

Figure 2. In 1981 42% of world population lived at $1.90 (2011 USD, PPP) and only 11% in 2013. This is despite the fact that world population increased during this time by 59%.

Finally, there is a utopian ethics which demands that people be guided by altruism in their mutual interactions and condemns markets, including the global ones, because they rely on the self-interest of the buyers and sellers. Needless to say, it is a display of irrationality, of deep ignorance about evolutionary psychology, and history, and it is an offense against common sense.

It is interesting that the proponents of nationalistic and utopian ethics share the same slogans. For example, they criticize the free trade in the name of “fair trade” – even though they give various meanings to this expression.

I know very well that the nationalistic ethics is much stronger in politics than the universal one. But this is not an argument in favor of the academics, who strengthen this bias by bashing globalization in the name of defending globalization’s “losers” in the rich countries, and who disregard its beneficiaries in the poor ones. At the minimum they should not pretend to represent a moral high ground, and they should not be regarded as such by other people.

III Crude Anti-globalism

1. Crude anti-globalism appears in two forms:

-

The anti-capitalist propaganda, based on utopian ethics and on a complete disregard of economic history and of analytical economics. It usually appears under the label of the “left”.

-

The nationalistic propaganda which is based on nationalistic ethics and targets foreigners as migrants or producers of imported goods. It is usually belonging for the “right”.

The main representatives of the crude anti-globalism stem from outside mainstream economics, even though some professional economists lend credibility to this phenomenon by focusing on those who are considered the losers in the developed world and on the inequalities ascribed to trade globalization.

2. Martin Wolf (2004) has brilliantly exposed the logical and empirical fallacies of crude anti-globalism. The main ones include:

-

Propositions to replace the globalized world with one consisting of many self-sufficient units;

-

Advocating replacing capitalism with “something nicer”;

-

Claiming that globalization destroys national states and democracy;

-

Demonizing multinational corporations;

-

Claiming that globalization is responsible for mass destitution by fostering increased inequality within and between nations.;

- Blaming globalization for the destruction of the environment, etc..

3. In the following I will deal with more sophisticated versions of anti-globalism (which sometimes border on the crude form). However, I would like to stress that the crude anti-globalism, with its false simplicity and emotionally loaded accusations, is a dangerous phenomenon which, for those very reasons, enjoys mass popularity. In that, it resembles the previous quasi-religious or nationalistic movements: communism and fascism. Therefore, the proponents of reason and of a liberal order should unmask the fallacies of crude anti-globalization in the mass media. The propaganda which does not meet a strong response tends to win.

IV Trade Globalization

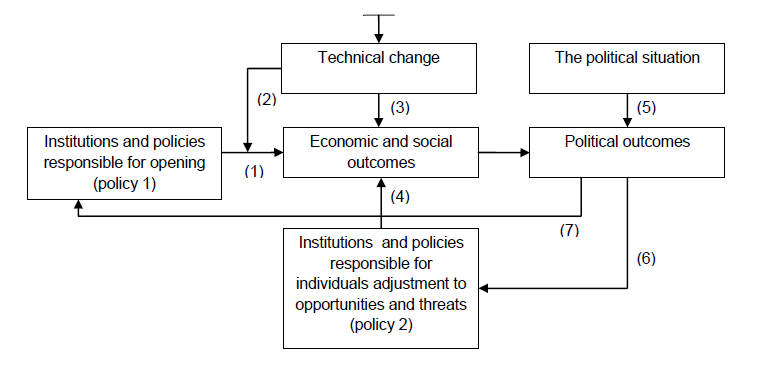

1. In discussing trade globalization one should consider two types of institutions and policies (for short: policies): those which determine the scope of a country’s openness to trade (Policy 1) and those which influence the individuals’’ possibilities and incentives to adjust to new opportunities and threats, including changes that are linked to trade opening (Policy 2). Socio-economic outcomes result from various factors. One of the analytical challenges is to isolate the impact of trade opening from that of other factors, especially of technological change (Autor et al, 2015) which, in turn, depends on countries’ institutional systems: there is not a good substitute for extensive and equal economic freedom within the framework of the rule of law.

Socio-economic outcomes influence politics even though there are many other factors. Figure 3. depicts these and other interactions. I will use it, first, to discuss the impact of globalization on the less developed countries, and, then on the rich economies.

Figure 3. Policies, globalization, outcomes 8

Figure 3. Policies, globalization, outcomes 8

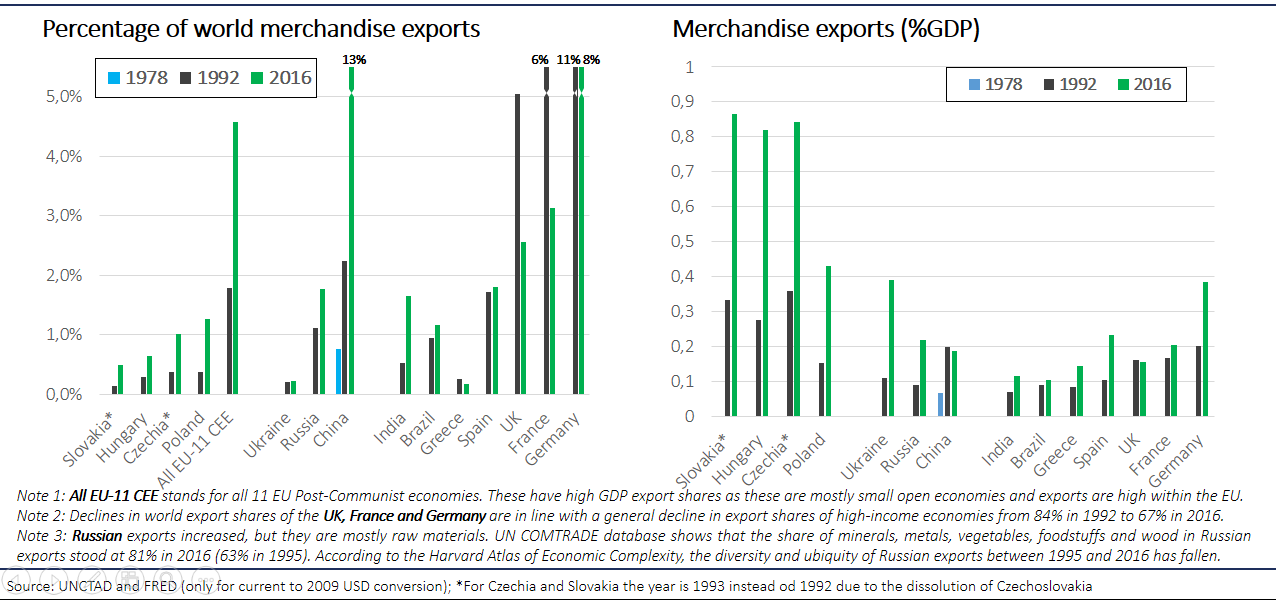

2. In speaking about trade globalization one must consider the demise of socialism, first in China, and later in the former Soviet bloc. This has opened the way to the market reforms in these countries, including the liberalization of trade (Figure 2.). There can be little doubt that these liberal reforms were hugely beneficial to the societies in the former socialist countries. For the counterexamples look to North Korea, Cuba and Venezuela.

Figure 4.Exports of post-communist economies pre- and post-transition, and selected other exporters.

Figure 4.Exports of post-communist economies pre- and post-transition, and selected other exporters.

3. The increase of exports (and imports) of the post-socialist economies depended not only on their radical institutional change but also on the appearance and spread of ICT-based technology, invented in the developed countries. This technology has allowed a rapid development of global value chains (R. Baldwin, 2016). This is an example of the interaction between radical institutional change in former socialist economies and modern technology stemming from the West in driving trade globalization. The largest beneficiaries on the exporting side have been, of course, China, and in Europe, Poland. Russia has increased its dependence on the production and exports of oil and gas.

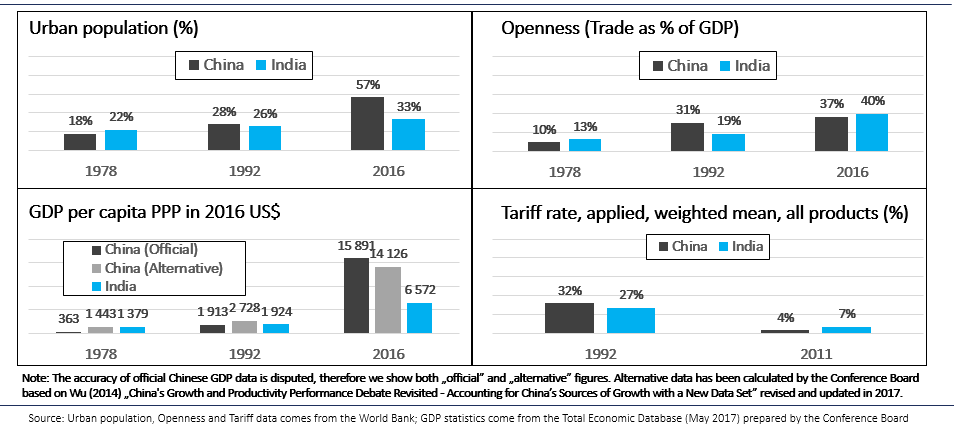

4. The socio-economic outcomes in poor globalizing countries depended not only on the scope of their trade opening (Policy 1), but also on their Policy 2, which determines the extent to which resources move in response to trade liberalization. Here it is interesting to compare China and India (Figure 3). As one can see, the structural shift from agriculture to manufacturing (proxied by the increase of urbanization) has been much larger in China than in India. The difference is largely due to the fact that India has had much stronger barriers to spatial and occupational mobility: poor infrastructure, poor education, heavy subsidization of agriculture, very restrictive labor laws which discourage private firms from hiring new people. (see: Kazmin, 2014, Shanmugaratnam, 2016). This is an example how bad Policy 2 limits the gains from trade globalization for the poor.

Figure 5.China and India urbanization has been much larger in China, contributing to better economic performance.

Figure 5.China and India urbanization has been much larger in China, contributing to better economic performance.

I will now move to political outcomes which one can link to the opening of the economy in the poorer countries. It appears to me that there have been very few protests against the results of this systemic institutional change, either in China or Eastern Europe. This is in contrast to anti-globalization protests in the rich countries

5. Let me now use Figure 3. to discuss the socio-economic outcomes and political reactions to trade globalization in the developed countries. In this case, Policies 1 refer to the trade liberalization and other market reforms in the poorer economies, and the trade agreements concluded between them and the rich economies, e.g. NAFTA. Policies 2 and outcomes in Figure 1 refer to the developed countries.

6. What strikes me is that the popular and academic discussions about the outcomes linked, rightly or wrongly, to trade globalization are recently dominated by the negative issues (messages), especially regarding the increase in income inequalities and the related topic of the globalization’s “losers”. This seems be more true of the US than of Europe, where the negative news focuses more on immigration. There are two main issues related to trade globalization in the developed economies: a) the role of import competition and technological change in producing outcomes criticized as negative by some observers and politicians and, more importantly, b) the role of policies which determine the individuals’’ adjustment. (Policy 2)

-

The relative role of import competition versus ICT-related technological change is subject to intensive empirical research (see, e.g. Parilla,2017.) Without going deeper into this literature I would like to note that job losses occur in the non-tradable sector, too, and, therefore, they cannot be ascribed to import competition, e.g. Uber, or automation of clerical functions. And much of the increased imports from less developed countries include intra-industry trade within the expanded global value chains, made possible by the ITC and IT technology, developed in the rich countries (Baldwin, 2016). Therefore, the increased import competition results from the interaction of the market reforms in the less developed countries, especially China, and modern technology from the rich countries. These developments, as I already mentioned, have provided enormous benefits to the poor people in the poorer part of the world (and to many people in the richer part of our globe). But in the west the popular discussions and the political debates focus on globalization’s “losers” and on the inequalities within the rich economies.

8. However, it is not most important that the popular focus on the “losers” and on inequalities often wrongly attributes these phenomena to import competition disregarding the role of modern technology. What matters more is that the only type of lastingly growing economy is a market economy with a lot of competition including that, based on innovations. And market competition always produces some winners and some losers, at least in relative sense (see: the Schumpeterian “creative destruction”). Backlash against trade globalization is, therefore, just a manifestation of an old phenomenon – a protest against competition. In the Middle Ages when the economy was shackled by monopolies, competition was morally condemned. The market revolution which started in the West in the early 19th century, has changed this norm: the “creative destruction” due to market competition has stopped being perceived in general as morally reprehensible. Recent attacks against import competition and globalization resemble the old morality.

9. However, the most important observation regarding the negative outcomes ascribed, rightly or wrongly, to trade globalization is this: job losses related to competition in general (including trade globalization) depend not only on the extent of opening (Policy 1) but also on the institutions and policies which determine the adjustment, i.e. the possibilities and incentives faced by of the affected individuals’ to move to other occupations and/or to better locations (Policy 2). The intense competition, a basic determinant for long economic growth, combined with policies that limit individual adjustment, is bound to produce many more losers that the same competition coupled with a better institutional and policy environment for individual adjustment.

There is a growing literature on the cross-country environment in policies 2 (e.g. “In the lunch” Schleicher, 2017). An economically and morally sensible conclusion is to improve policies 2 instead of bashing import competition or other forms of market competition.

11. If the institutional environment for individual adjustment to increased import competition (and to competition in general) is weak, there is a growing pressure on the part of the losers to limit competition, rather than to improve policies 2. To what extent this pressure is translated into policies 1 depends on the details of the political situation and on the kind of individuals’ operating in politics. It appears to me that the recent protectionist tendencies in the US, present both among the Republicans and Democrats, are due to the fact that the people who perceive themselves as losers have had a strong presence in the swing states. The increased political importance of the losers is not so typical of other democratic countries. But, of course it is very unfortunate that such a situation has appeared in a country that is globally important and that used to be a global leader in external liberalization.

V Financial Globalization

1. The number of fallacies in the discussion of financial globalization exceeds that regarding trade globalization, even though there are some common elements; especially: a) blaming both globalizations for the negative outcomes, which are caused, in fact, by wrong policies, and b) disregarding the benefits from good globalization policies, i.e. those that allow for external liberalization and the individuals’’ adjustment to new opportunities and threats.

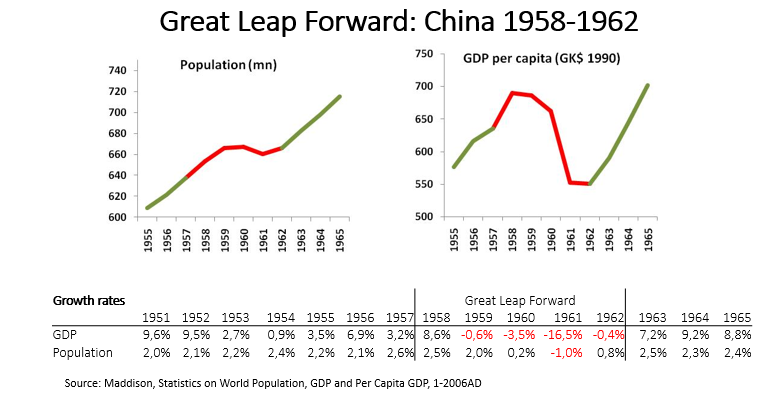

2. Financial globalization is often associated with the financial crises which, in turn, are blamed on market capitalism, and especially on its financial sector. However, the deepest crises occur in the non-market regimes, which, by necessity, display a heavy concentration of political power (socialism). The reasons for this are clear: rulers without external constraints can launch and implement disastrous policies.

Figure 6. Socialism – political power, fused with the economic power, is unlimited and almost totally crowds out legal markets, e.g.

Figure 6. Socialism – political power, fused with the economic power, is unlimited and almost totally crowds out legal markets, e.g.

Therefore, the most important safeguard against the deepest crises consists in the division of powers within the society, which includes not only the checks and balances within the state but also private ownership and markets.

3. It is very superficial to blame the financial crises under capitalism on the markets. Contrary to the textbook presentation, these crises are not a phenomenon which occurs regularly across countries and time. The opposite is true: the incidence of financial crises has been very uneven, which strongly suggests that the differences in countries’ policies are a deeper determinant of financial crisis (see: Selgin, Calomirs). And such policies have been identified: they generally distort the behavior of the financial markets by encouraging excessive lending and borrowing, i.e.. fiscal and private credit booms. These policies include excessively low interest rates (due to interest rate subsidies or low central bank rates), “too big to fail policy”, tax regulations which favor borrowing relative to equity capital, over- generous deposit insurance, etc. Various combinations of these and other policies were also behind the recent global financial crisis (GFC).

4. A financial crisis becomes global when it includes a globally important economy, which nowadays is the US. However, even though the recent GFC is called “global”, its impact has been far from uniform: certain countries were affected much more heavily (e.g. Spain, Ireland, Greece) than others (e.g. Germany, Poland). The popular metaphors “contagion” and “domino effect” are misleading: countries’ vulnerabilities to external financial shocks differ, and this depends again on their institutions and policies.

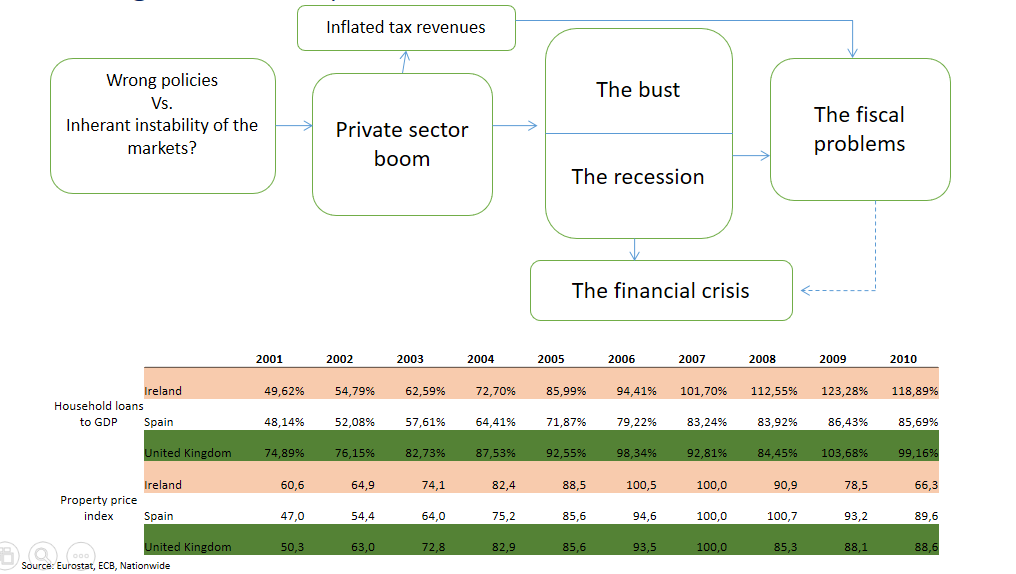

5. One can distinguish two types of financial crisis, which have the form of the boom – bust episodes: the financial-fiscal and the fiscal-financial.

In the former case, at the start there is a real estate boom which turns into the bust, causing a recession which spills over to public finance (the deficit explodes). Example include Spain, Ireland, and Britain.

Figure 7: The dynamics of the Financial-Fiscal Crisis

Figure 7: The dynamics of the Financial-Fiscal Crisis

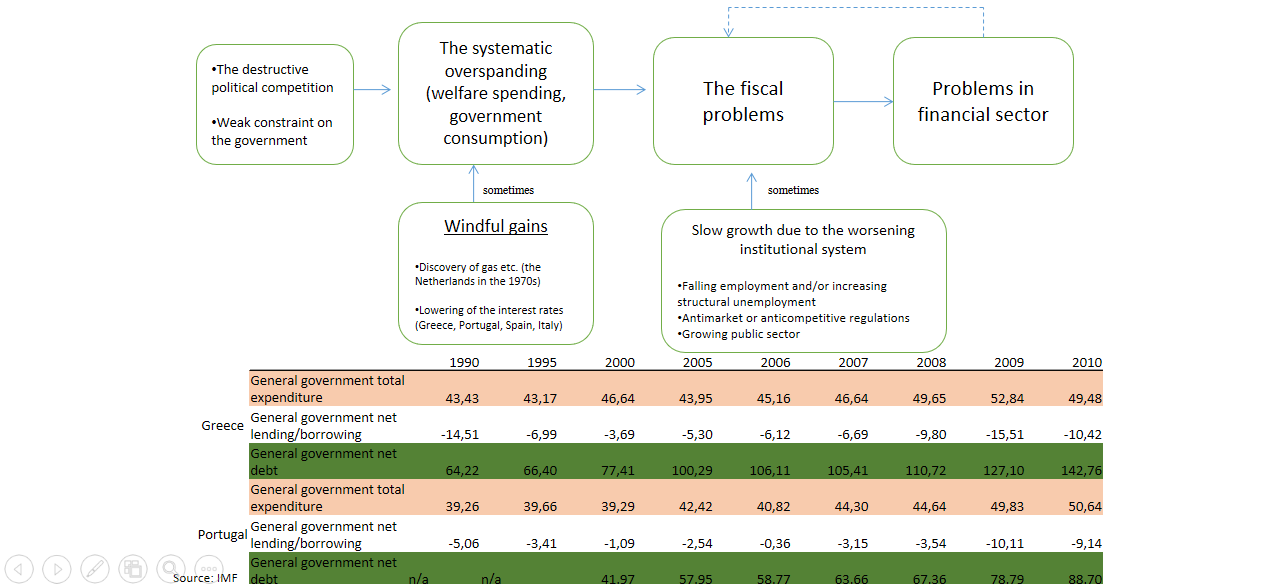

In the case of fiscal-financial crisis at the beginning there is a fiscal boom, which, when burst, spills over to the financial sector, i.e. affects the banks which have financed the government borrowing spree. The best example here is Greece until 2010. 15

Figure 8: The dynamics of Fiscal- Financial Crisis

Figure 8: The dynamics of Fiscal- Financial Crisis

6. Even though the deeper causes of the financial crises include various faulty policies, one cannot deny, that the risks of various disturbances in a financially interconnected world are higher than in a world where countries are financially isolated from each other. However, these risks have to be compared with the huge gains due to financial globalization if the right institutions and policies are in place.

7. Institutions in the host countries determine not only the amount of the incoming financial flows (Policy 1 in Figure 1) but also their composition (Policy 2).

As I noted in section I, FDI is from the point of view of economic growth the most important financial inflow because of its strong link to technology transfer. However only some countries get large amounts of FDI: those with institutions and policies which respect private property rights and create a reasonable expectation that sudden policy reversals will be avoided. Very large economies like China can attract for a certain time, large amounts of FDI even if these fundamentals are weak.

Some other financial inflows, e.g. portfolio capital, international bank lending, are less strongly linked to the host country’s economic growth. This is especially true if these inflows finance mortgage credit booms, or fiscal booms. However, one should remember that these excesses are largely due to various combinations of bad policies rather than the inflows themselves. 16

VI Concluding Comments

Let me finish with some observations and recommendations:

-

The globalization process depends on the policies in the respective countries, especially the large ones, and on other factors, especially on the technical change. One should focus on a policies so that are no reversals in the degree of countries external opening and that their institutions allow for a better individuals’ adjustment to new opportunities or threats. The globalization process may slow down if the technical change changes the distribution of profitable locations of economic activity in the world, or because of the inevitable slowdown in China.(Bordo, Eichengreen…)

-

In discussing the outcomes ascribed to globalization one should distinguish the symptoms from the causes. Globalization is to often blamed for the results of bad policies, especially those which hamper individuals’ adjustment to new pressures, and those which encourage them to take excessive risks.

-

Crude globalization, based on the nationalistic or utopian ethics is, indeed, very demagogic. However, it should not be neglected because the emotional irrationality appeals to many people, and therefore, can, have dangerous political consequences

-

In defending the achieved level of globalization one should appeal to its beneficiaries who would become losers, if policies turn to trade protectionism. This is especially relevant for the US.

-

The European Union can and should play the role of the center in defending the free trade in the world. At the same time it should resist the protectionist pressures within its own Single Market.

*I would like to thank Rafał Trzeciakowski, Kasia Szczypska and Jan Kożuchowski for their assistance in preparing this paper.