In public debate one can frequently find support for significant state ownership in the economy, citing the need to protect strategic national interests, including public safety and order. [1] Politicians often argue that privatizing companies with State Treasury involvement would lead to their acquisition by entities hostile to Polish interests. [2] A report by the Ministry of State Assets from November 2023 described State Treasury companies as a “key element of the national security system.”[3]

This is a clear manipulation. Both the Polish Constitution and EU treaties allow for the limitation of economic freedom to ensure public safety and order. [4] Additionally, Polish lawmakers have introduced non-ownership mechanisms to safeguard these values.

Moreover, Poland has an exceptionally high level of state ownership in the economy, reportedly the highest in the European Union. For example, economists M. Bałtowski and G. Kwiatkowski indicate that the state’s share among the top 100 companies, measured by revenue and assets, amounts to nearly 50%—a level surpassed only by Russia, Egypt, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia, and China among the countries they studied. [5]

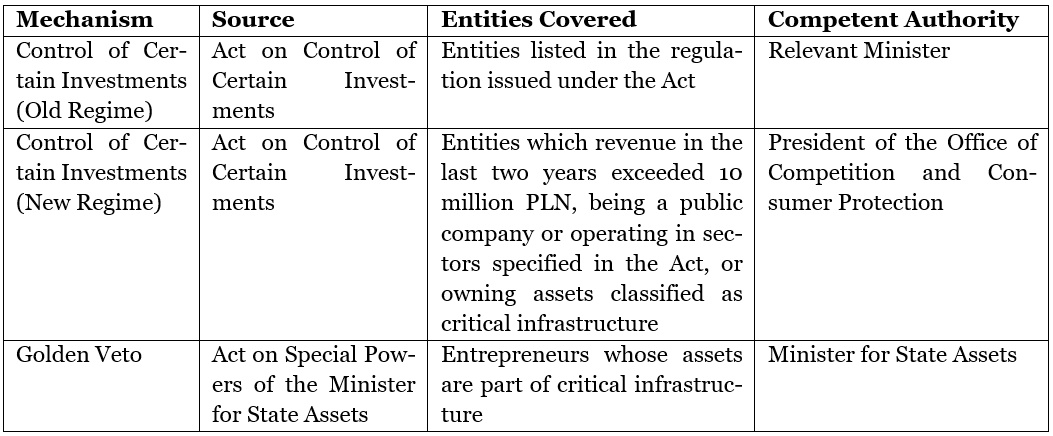

Table 1: Overview of Mechanisms Subject to Analysis

Foreign Investment Control

The Act on Control of Certain Investments came into effect in 2015,[6] introducing into Polish law a mechanism, similar to those used in countries like Germany and Austria, for controlling foreign investments to safeguard public safety and order[7].

This law provides two distinct mechanisms of foreign investment control:

- Limited to specific companies listed in a regulation – where the controlling authority is the relevant minister overseeing the branch of administration linked to the economic sector in which the entity operates (referred to as the “old regime”)[8].

- Applicable to all entities meeting statutory criteria – where the President of the Office of Competition and Consumer Protection conducts the oversight (referred to as the “new regime”)[9].

Under the old regime, entities subject to this mechanism were listed in a regulation of the Council of Ministers, which is updated annually[10]. Currently, it includes 17 companies from the energy, telecommunications, and defense sectors, such as Telesystem-Mesko, Implementation Center, Emitel, Orange Polska, and Orlen. Each company is assigned a supervising minister responsible for its oversight.

According to the Act, the acquisition of a significant part or control over a company must be reported to the relevant minister. In general, a significant part is understood as acquiring at least 20%, 25%, or 33% of voting rights at a shareholders’ meeting or a share of the company’s capital. Meanwhile, acquiring control typically means obtaining at least 50% of the aforementioned voting rights or shares.

Both the acquisition of significant part and control without notification or despite the minister’s objection are, as a rule, null and void by law. The Act stipulates that the minister controlling the transaction may object if it is justified by objectives such as:

- Protecting the independence and territorial integrity of the state;

- Ensuring the freedom, rights, and safety of citizens;

- Environmental protection;

- Preventing social or political actions or phenomena that negatively impact Poland’s NATO obligations and foreign relations;

- Ensuring public order, state security, or addressing essential needs to protect public health and life.

These regulations provide the legal framework for exceptions to the EU’s free movement of capital. The treaties allow the introduction of such restrictions, particularly for the protection of public safety and order, provided they do not result in arbitrary discrimination and are interpreted narrowly and applied proportionally[11].

New Regime

The new regime was introduced into Polish law in July 2020, in response to the pandemic and international circumstances disrupting the market and competition, and is set to expire in mid-2025. It places the authority for oversight in the hands of the President of the Office of Competition and Consumer Protection (UOKiK). It is worth noting that selecting this institution as the competent authority is rather unusual. In comparable laws in Germany, Austria, or the United Kingdom, the responsible body is typically the minister.

The new mechanism covers a much broader range of entities than the 2015 regulations, which was explained by the perceived insufficiency of the narrow scope of the previous legal provisions. [12] These entities include, among others, companies headquartered in Poland whose revenue exceeded 10 million € in the two years preceding the notification and that meet one of the following criteria:

- They are a public company;

- Their business activity relates to one of the 21 areas listed in the Act, such as the generation of electricity, pipeline transport, underground storage of fuels or natural gas, telecommunications, manufacturing of medical equipment or pharmaceuticals, cargo handling in inland ports, or the processing of meat, dairy, grains, fruits, and vegetables;

- They own assets that form part of critical infrastructure or develop certain types of software.

It is important to note that this mechanism applies only to investors who do not have their headquarters or residence in an EU or European Economic Area member state.

One striking aspect is the exceptionally broad discretionary power granted to the President of UOKiK. The mere potential threat to public safety and order or the possible negative impact on projects and programs in the interest of the European Union is enough to issue an objection. Legal scholars have pointed out that, despite the inclusion of broad general clauses in the Act, this does not grant the authority the right to interpret them arbitrarily.

In practice, however, the controlling body should have no difficulty finding arguments to justify a decision of objection. Therefore, judicial oversight of such decisions by an administrative court is particularly important[13]. Under EU law, it is also clear that exceptions to the free movement of capital must be interpreted narrowly, which further limits the risk of abuse of these powers. [14]

Minister’s of State Assets Golden Veto

In addition to the authority to control foreign investments, the Minister of State Assets holds a special tool for protecting public interests known as the “golden veto.” This instrument can be applied in the electricity, oil, and gas sectors.

Under the provisions of the Act on Special Powers of the Minister of State Assets,[15] the minister may object to resolutions or other legal actions taken by companies that involve disposing of assets forming part of a critical infrastructure if such actions pose a real threat to the infrastructure’s operation, continuity, or integrity. The minister can also object to other company resolutions, such as those concerning the dissolution of the company, relocating its headquarters abroad, or adopting operational, financial, investment, or strategic plans. By its nature, this instrument is used sparingly as it pertains to a limited number of specific situations.

It is worth noting that the 2010 law is not the first piece of legislation regulating the so-called “golden share” of the State Treasury. Since 2005, the Act on Special Powers of the State Treasury and their Execution in Companies of Significant Importance for Public Order or Public Safety (repealed by the 2010 law) has been in effect. This institution has been known in European legal systems since the 1980s and is used in various EU member states as an exception to the Treaty’s principle of free movement of capital. [16]

Sector-Specific Regulations

In infrastructure sectors, business operations face significant regulatory restrictions. In fields such as energy, telecommunications, and railways, specialized authorities regulate the market through administrative actions. These include the President of the Energy Regulatory Office, the President of the Office of Electronic Communications, and the President of the Office of Rail Transport. This model is heavily influenced by EU regulations and essentially operates on the same principles across the entire European Union. [17]

It is important to note that there are nearly fully privatized infrastructure sectors, such as the telecommunication sector in Poland. According to the regulator himself, this market is functioning sufficiently well to allow for the relaxation of stricter regulatory measures. For example, the President of the Office of Electronic Communications does not currently designate any company as obligated to provide universal service nationwide, as the market mechanism guarantees the appropriate quality, affordability, and availability of services[18].

Summary

The legislator has addressed most of the concerns related to potential threats to public safety and order that could arise from the state’s withdrawal from direct involvement in the economy. The mechanisms in force in Poland fundamentally do not differ from comparable solutions in Western countries, where state participation in the economy is generally much lower. Paradoxically, the obstacle to fully implementing these mechanisms is the continued significant level of state ownership in the economy. These mechanisms are difficult to apply broadly since they are intended to replace the state’s direct involvement in the economy, which remains extensive in certain sectors.

From the perspective of the economic system stipulated in the constitution, it is desirable to significantly reduce state ownership in the economy while proportionally protecting public interests through law and the actions of public administration bodies. There is no doubt that under Article 20 of the Polish Constitution, direct state participation in market competition is allowed only in exceptional cases. [19] Therefore, the state is obliged to limit its involvement in the economy so that private ownership—autonomous from the state—takes precedence. [20] State influence on economic activity should be exercised through legal tools rather than direct market intervention. [21]

However, caution must be taken to ensure that politicians and officials do not exploit these mechanisms under the pretext of public safety and order for protectionist purposes. Such actions would constitute an abuse of these regulations, in conflict with both the constitutional model of a social market economy—which explicitly excludes protectionism—and the EU’s treaty freedoms.

References

[1] Currently, the list of companies with State Treasury participation includes as many as 422 entities (see: Prokuratoria Generalna Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej, Wykaz spółek z udziałem Skarbu Państwa według stanu na dzień 31.03.2023 r., https://dane.gov.pl/pl/dataset/1198/resource/48179/).

[2] Petru wzywa do prywatyzacji strategicznych polskich spółek. Putin polubi ten wpis?, Portal TV Republika, May 21, 2023, https://tvrepublika.pl/Petru-wzywa-do-prywatyzacji-strategicznych-polskich-spolek-Putin-polubi-ten-wpis,146416.html; Jacek Sasin: Spółki Skarbu Państwa gwarantem bezpieczeństwa gospodarczego Polski, Ministerstwo Aktywów Państwowych, July 25, 2022, https://www.gov.pl/web/aktywa-panstwowe/jacek-sasin-spolki-skarbu-panstwa-gwarantem-bezpieczenstwa-gospodarczego-polski; D. Tusk: „Państwo powinno mieć współkontrolę, być obecne w spółkach o strategicznym znaczeniu, głównie energetycznymi, przesyłowymi”, money.pl, January 12, 2024, https://www.money.pl/gospodarka/spolki-strategiczne-w-rekach-panstwa-nie-jestem-skrajnym-liberalem-6984053207357984a.html.

[3] Ministry of State Assets, Spółki z udziałem Skarbu Państwa. Działania i wyniki 2016–2023, Warsaw, November 2023, p. 2.

[4] See P. Czarnek, Wolność gospodarcza. Pierwszy filar społecznej gospodarki rynkowej, Lublin 2014, p. 233.

[5] B. Jabrzyk, FOR Communication 9/2024: Privatization – the new government follows the path of Law and Justice, March 18, 2024 https://for.org.pl/en/2024/03/18/for-communication-9-2024-privatization-the-new-government-follows-the-path-of-law-and-justice/

[6] Tekst jednolity: Dz.U. z 2023 r. poz. 415.

[7] Uzasadnienie poselskiego projektu ustawy o kontroli niektórych inwestycji, Sejm print 3454 (VII term), p. 17–18.

[8] See K. Czapracka, M. Gac, J. Gubański, I. Małobęcki, Kontrola inwestycji zagranicznych – wstępna ocena polskiego ustawodawstwa i praktyki w kontekście europejskich i światowych trendów, „internetowy Kwartalnik Antymonopolowy i Regulacyjny” nr 4, 2022, p. 9.

[9] Ibidem, p. 10.

[10] Currently, it is the Regulation of the Council of Ministers of December 27, 2023, on the list of entities subject to protection and their respective supervisory authorities (Dz. U. poz. 2812).

[11] See: M. Mataczyński, M. Saczywko, in: Ustawa o kontroli niektórych inwestycji, p. 33 et seq.; judgment of the Court of Justice of 18 June 2020, Commission v. Hungary (Transparency of Associations), C-78/18, ECLI:EU:C:2020:476, para. 76 and the case law cited therein.

[12] Uzasadnienie rządowego projektu ustawy o dopłatach do oprocentowania kredytów bankowych udzielanych na zapewnienie płynności finansowej przedsiębiorcom dotkniętym skutkami COVID-19 oraz o zmianie niektórych innych ustaw, p. 38, https://www.sejm.gov.pl/Sejm9.nsf/druk.xsp?nr=382.

[13] M. Bałdowski, Ustawa o kontroli niektórych inwestycji jako mechanizm zapewniający bezpieczeństwo energetyczne, „internetowy Kwartalnik Antymonopolowy i Regulacyjny” 2019, no. 5, p. 129–130.

[14] See: judgment of the Court of Justice of 11 November 2010, Commission v. Portugal, C-543/08, para. 85 and the case law cited therein.

[15] Tekst jednolity: Dz.U. z 2020 r. poz. 2173.

[16] See K. Pawłowicz, „Złota akcja” Skarbu Państwa jako instytucja prawa publicznego, „Państwo i Prawo” no. 2, 2007,p. 30–40.

[17] For example, the requirement to establish an independent regulator for the gas and electricity markets arises from Directives 2009/73/EC and 2019/944.

[18] See Sprawozdanie z działalności Prezesa UKE za 2022 rok, p. 4.

[19] L. Garlicki, M. Zubik, Artykuł 20, in: Konstytucja Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej. Komentarz, L. Garlicki, M. Zubik (red.), t. I, Warsaw 2016.

[20] Judgment of the Constitutional Tribunal of 21 March 2000, K 14/99.

[21] Judgment of the Constitutional Tribunal of 17 January 2001, K 5/00.

Continue exploring:

1989 – Beginning of 35 Years of Liberal Transformation

Poland’s Civic Coalition Pre-election and Presidential Election 2025