The energy sector covers the trade of two fundamental goods: energy (including heat) and fuels. An energy-sector enterprise may operate in the fields of generation, conversion, transmission, storage, trading, or distribution of these goods.

The sector is characterized by high concentration, meaning that relatively few firms operate on the market due to high entry barriers and the presence of natural monopolies. Traditionally, the sector has also featured a significant state presence. In Poland, the origins of the current structure can be traced to the consolidation waves of 2000, 2004, and 2006, during which smaller entities were merged into larger groups. The last of these waves, carried out under the government’s Power Sector Programme, resulted in the model that exists today, with four major energy groups. The effect of consolidation was a substantial increase in market concentration. The Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI), which measures concentration levels in the economy, rose in electricity generation from around 800 in 2003 to over 1800 in 2008. An HHI between 1800 and 5000 indicates high concentration.

Since then, however, market concentration has gradually declined due to liberalization and privatization processes. EU legislation played a fundamental role, particularly the so-called Liberalization Packages, the most recent adopted in 2009—separately for electricity and gas. These introduced, among other things, third-party access (TPA) rules and unbundling requirements (separating distribution from generation). In large part, the impulse for liberalising and opening the sector originated in Brussels. It is worth noting, however, that the obligation to open markets and uphold competitive market principles stems directly from Article 20 of the Polish Constitution, which establishes the model of a social market economy as the foundation of Poland’s economic system—one that requires the protection and support of free competition. This has fundamental systemic importance, as it prevents excessive market-power concentration and its spillover into the political sphere.

State and Competition in Energy Sector

State involvement in the energy sector serves several objectives. The Energy Law lists the variety of them: “The purpose of this Act is to ensure energy security, the efficient and rational use of fuels and energy, the development of competition, counteracting the negative effects of natural monopolies, taking into account environmental protection requirements, obligations arising from international agreements, and balancing the interests of energy undertakings and consumers of fuels and energy.” Similar objectives are outlined in the policy Poland’s Energy Policy until 2040, which emphasises “energy security—while ensuring economic competitiveness, energy efficiency, and reducing the environmental impact of the energy sector—taking into account the optimal use of domestic energy resources.”

The abovementioned objectives reflect the constitutional foundations for state regulation of the energy sector. Within Poland’s model of a social market economy, the state is obliged both to safeguard competitive market and to mitigate the negative effects of its mechanisms. However, state intervention must not undermine the essence of the market and should rely on legal and regulatory instruments rather than on direct state participation in the economy. The social market economy is based on private ownership, as additionally emphasised in Article 20 of the Constitution. Mitigating undesirable market outcomes is achieved through the actions of the competition authority, as well as through the work of the sectoral regulator, which balances the interests of consumers and energy companies. In all other respects, the state is obliged to leave the sector to market competition, which it has a duty to promote.

The state influences the sector through a variety of institutions and mechanisms. The regulatory authority applying administrative-law instruments, including issuing licenses, is the President of the Energy Regulatory Office (URE). The minister responsible for state assets exercises ownership supervision; legislative instruments are exercised by the minister of energy; the President of the Office of Competition and Consumer Protection (UOKiK) issues decisions on anti-competitive practices by energy companies and authorizes concentrations in the sector. Two institutions are responsible for promoting competition: the President of URE, who must take the promotion of competition into account when making decisions concerning the sector, and the President of UOKiK, who by default acts as the national competition authority.

The state does not need—and indeed should not—maintain ownership at the level currently observed in Poland’s energy sector. Electricity generation and transmission remain almost entirely state-controlled, and four of the five key electricity distribution system operators are state-owned. This persists despite the existence of legal mechanisms designed to safeguard the public interest in the functioning of the sector—an arrangement that is, at the very least, questionable from the perspective of the constitutional economic system.

How Much State in Energy Sector?

In Poland, politicians tend to view a strong state presence in the energy sector as something natural and unavoidable—as if it were an iron law of the economy. Yet the only entities on the Polish energy market not controlled by the state are E.ON, the electricity distributor in Warsaw, and ZE PAK S.A., active in electricity generation. Meanwhile, across Europe there are very different models of state involvement in the energy sector—from France’s heavily nationalized system to the United Kingdom’s nearly fully privatized model.

France

France is an example of exceptionally strong state involvement in the energy sector. In recent years—particularly since Russia’s aggression against Ukraine—this presence has only intensified. A notable example is the renationalization of shares in EDF, one of the three largest suppliers of gas and electricity in France, which brought under full state ownership the portions of the company that had previously been privately held.

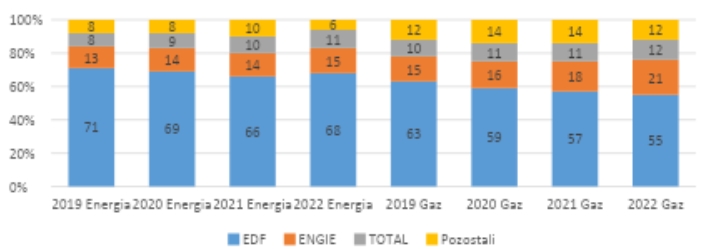

Figure 1. Changes in Market Share in the French Electricity Market (2019–2022)

As shown in the figure above, in both the electricity and gas markets the three largest companies controlled nearly the entire market. Of these three, only TotalEnergies, the smallest player in both sectors, currently has no state ownership. However, some commentators argue that the French government could legally acquire a single share and convert it into a “golden share,” granting it special control rights. As noted earlier, EDF, which holds the dominant position in the electricity supply market, is 100% state-owned. In the case of Engie, second in electricity and first in gas, the French Treasury owns 23.64% of the shares, which translates into 34.5% of voting rights at the general meeting. This demonstrates the significant influence the French government exerts over both markets.

However, state involvement extends far beyond owning shares in individual suppliers. A similarly high degree of state presence can be observed among transmission and distribution system operators. For instance, the electricity transmission system operator RTE is not only a subsidiary of EDF—which itself is fully state-controlled—but its operations are also heavily influenced by CRE, the French equivalent of Poland’s Energy Regulatory Office.

In the gas sector, the largest transmission system operator, GRTgaz, is majority-owned by Engie (around 60%). Only the second gas-transfer operator TSO – TEREGA, operating in south-western France, has no ownership links to the French state or to the major state-linked energy groups EDF and Engie. For distribution system operators, the situation mirrors that of RTE: the vast majority of electricity distribution networks (approximately 95%) are managed by Enedis, a subsidiary of EDF, while around 77% of French consumers receive gas from networks operated by GRDF, a subsidiary of Engie.

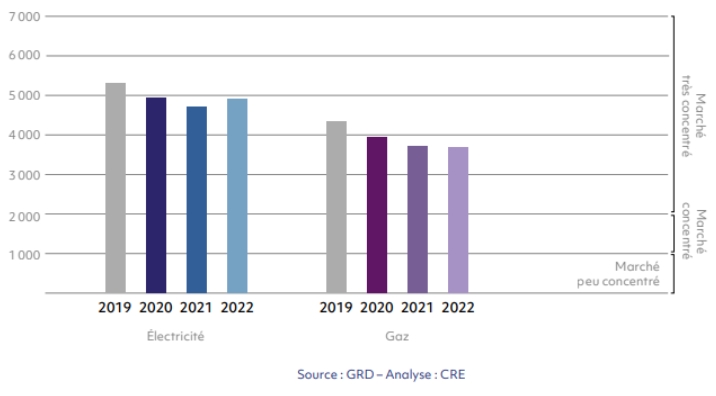

All of this confirms that the French energy market is highly concentrated, which is reflected in France’s comparatively high HHI levels relative to other EU Member States.

Figure 2. Changes in the HHI Index for French electricity and gas markets in the household sector over time

Figure 3. Changes in the HHI Index for electricity and gas markets in the household sector over time compared with selected European countries

United Kingdom

United Kingdom is at the opposite end of the spectrum from France in terms of state involvement in the energy sector. Due to Brexit-related factors, two distinct regulatory systems operate in the country: one for Northern Ireland (with its own regulator and links to the Irish and EU energy systems) and another for the rest of the UK, regulated by OFGEM. This analysis focuses on the latter. The UK stands out particularly in the structure and ownership of its electricity and gas transmission system operators.

For many years, the electricity transmission system operators in Great Britain were entities entirely independent of the state. These included: National Grid, responsible for the transmission network in England and Wales; Scottish Hydro Electric Transmission, operating in northern Scotland; SP Transmission, operating in southern Scotland. Each of these operators was a subsidiary of a different company, and each had major international investment funds among its largest shareholders. This situation changed in recent years with the creation of a new entity: the National Energy System Operator (NESO). NESO is responsible for planning the layout of electricity and gas transmission infrastructure and has taken over the tasks previously held by the electricity TSOs. Legally, NESO is a wholly state-owned company, although—according to its founding principles—it is and will remain operationally independent from the government.

The situation somewhat differs for the gas transmission system operator. Here, a single company—National Gas—operates across the entire country, and it is majority-owned by investment funds. State influence on the gas TSO therefore comes primarily through the regulator, OFGEM.

For distribution system operators (DSOs) in the UK, ownership resembles that of the gas TSO. Private ownership predominates: all four gas DSOs and all six electricity DSOs are owned either by international consortia or global investment funds. The supply segment is more mixed, with some companies having state ownership links—but not necessarily to the British state (e.g., France’s EDF). Nevertheless, the majority of the 21 electricity and gas suppliers are private entities. Among these, six suppliers clearly dominate the market: British Gas, Octopus Energy, E.ON, OVO, EDF, and Scottish Power which hold a significant majority of shares in the electricity and gas markets.

Figure 4. Market Share in the UK gas supply market over time

Figure 5. Market Share in the UK electricity supply market over time

However, as the figures above show, these six companies have not always dominated the market. This indicates a dynamic level of competition, which is also reflected in the UK’s HHI levels (Figure 3), demonstrating relatively low market concentration compared with other European countries.

Belgium

A different model can be observed in Belgium, where the federal structure of the state has a significant impact on the energy sector. This is clearly visible looking at the regulators: Belgium has four regulatory bodies—one at the federal level (CREG) and three regional regulators (VREG in Flanders, CWaPe in Wallonia, and Brugel in Brussels). However, the influence of federal structures extends well beyond regulatory oversight. Regional differences are particularly pronounced among distribution system operators (DSOs). For example – in the Brussels region, there is only one DSO: Sibelga; In Flanders, there is also a single operator: Fluvius; In Wallonia, five DSOs operate, with the two largest—RESA and ORES—managing most of the regional distribution network (including all gas distribution).

Another characteristic of the Belgian energy and gas market is the significant ownership share held by local governments. For instance, Fluvius is 100% owned by 300 Flemish municipalities, which are legally prohibited from selling their shares; Sibelga is entirely owned by the 19 municipalities of the Brussels Capital Region; In Wallonia, the largest DSO, ORES, is also 100% controlled by local governments.

Local governments are not limited to DSO ownership. They are also major shareholders in the parent company of the electricity transmission system operator, Elia—their holding company owns 44.8% of shares. Similarly, the parent company of the gas transmission operator, Fluxys, is majority-owned by a local government-holding. Interestingly, the Belgian federal government also holds a golden share in Fluxys Belgium, the gas TSO.

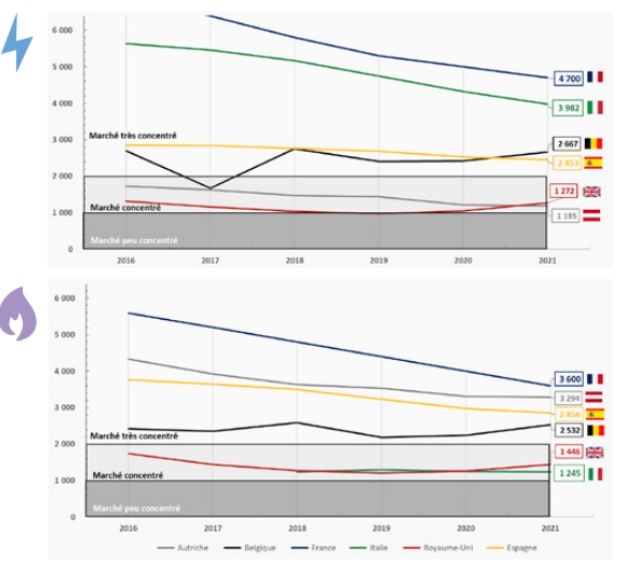

As of 2024, Belgium had 15 active suppliers on the electricity and gas retail markets, marking a decrease compared with previous years (Figure 6). The largest of these was Engie, which held the highest market share in electricity and gas supply across all Belgian regions. Nevertheless, aside from Brussels and its surroundings, Belgium was not devoid of competition. This is reflected in the relatively moderate HHI levels for electricity and gas, which remain lower than those of more concentrated markets such as France (Figure 3).

Figure 6. Changes in the number of electricity and gas suppliers in Belgium over time

Figure 7. Changes in the HHI Index for the electricity and gas markets in Belgium over time

Germany

In Germany, the institutional framework for regulating the energy sector is roughly similar to that of Poland. The sector is overseen by a sectoral regulator—the Federal Network Agency (Bundesnetzagentur)—and by the competition authority, the Federal Cartel Office (Bundeskartellamt). Ownership policy is carried out by the federal government as well as by the governments of the individual federal states (Länder). However, the direct state presence in the German energy market is significantly lower than in Poland.

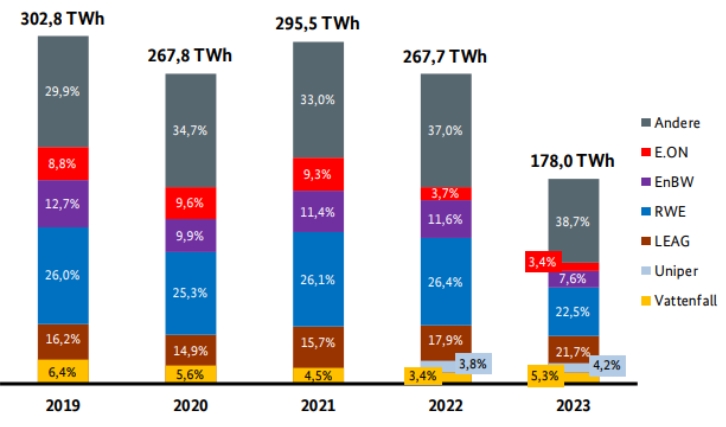

In the electric power sector, the generation and distribution segments are dominated by the same vertically integrated companies. The five largest electricity producers—responsible for slightly more than 50% of installed capacity—are RWE, EnBW, LEAG, Vattenfall, and Uniper. These same companies, together with E.ON, are also the largest distribution system operators.

Figure 8. Market share of the largest companies in domestic electricity production (excluding imports)

Among these six major companies, the German state holds shares only in EnBW, which is partly owned by the state of Baden-Württemberg (46.75% of shares; another 46.75% is owned by an association of Upper Swabian municipalities). RWE and E.ON are private companies whose shares are largely held by private institutional investors. The same is true for LEAG, whose owners are Czech institutional investors: Energetický a Průmyslový Holding and PPF Group. Uniper previously belonged to the Finnish state-owned company Fortum.

However, at the end of 2022 it was nationalized by the German federal government, which acquired over 99% of its shares. This purchase was a crisis intervention—Uniper, heavily exposed to Russian gas trading, incurred severe financial losses following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and was intended to secure the stability of gas supply in Germany. The nationalization is likely temporary, as plans for the company’s re-privatization have already been announced. Vattenfall, in turn, is a Swedish state-owned enterprise fully controlled by the Swedish Treasury.

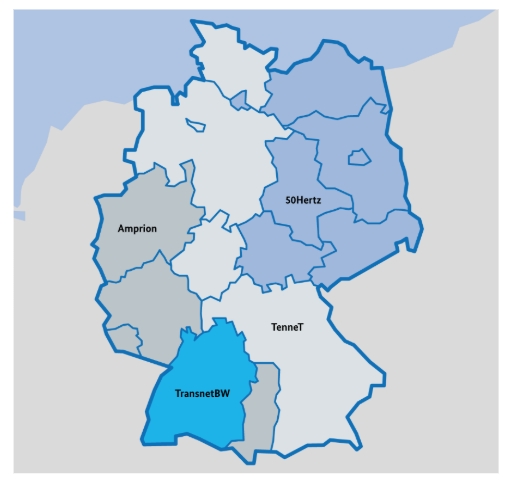

In the field of electricity transmission, Germany has four transmission system operators (TSOs): 50Hertz, Amprion, TenneT, and TransnetBW.

Map 1. Electricity Transmission System Operators in Germany

State involvement in the transmission segment is also limited. TransnetBW GmbH, originally carved out of EnBW, includes a minority stake held by the federal government. Amprion is 75% owned by a private consortium of institutional investors and 25% by RWE. 50Hertz is 80% owned by the Belgian transmission operator Elia and 20% by the German state development bank KfW. TenneT is owned by a Dutch state-owned company wholly controlled by the Dutch Ministry of Finance.

These examples—drawn from countries pursuing highly diverse approaches to energy-sector regulation—show that the Polish model, characterized by the dominance of state-owned entities, is not universal or inevitable. As Germany and the United Kingdom illustrate, moving away from this model is possible and depends primarily on political choice.

Competition in the Energy Sector – A Lost Decade?

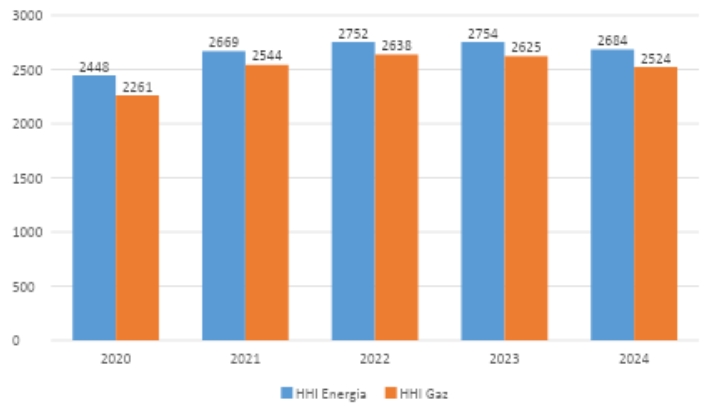

Since the introduction of the Power Sector Program in 2006, the level of concentration in Poland’s electricity market had been steadily declining. This resulted from both government policy (developing competitive electricity and gas markets was one of the key objectives of national energy policy) and the efforts of the sectoral regulator and the competition authority. Threats to increasing competition emerged when concepts such as “national champions” and the “repolonization” of foreign-owned companies entered the public debate. Already in 2010, the government planned to establish a national energy champion.

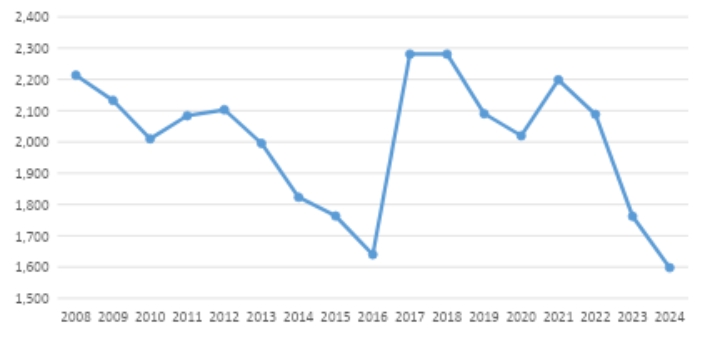

In 2017, market concentration in electricity generation drastically increased following the nationalization of EDF Polska. At the time, the President of the Energy Regulatory Office stated that the Polish energy market had “returned to its starting point after 20 years.” The negative consequences of this nationalization were only overcome last year, when concentration levels in electricity generation fell back to those observed before 2016. This was driven by long-term growth in renewable energy and the declining share of fossil fuels in the national energy mix.

Figure 9. HHI in the electricity generation subsector. FOR’s elaboration based on annual reports of the President of the Energy Regulatory Office

Competition in Energy Sector – Poland at the Backdrop of the EU

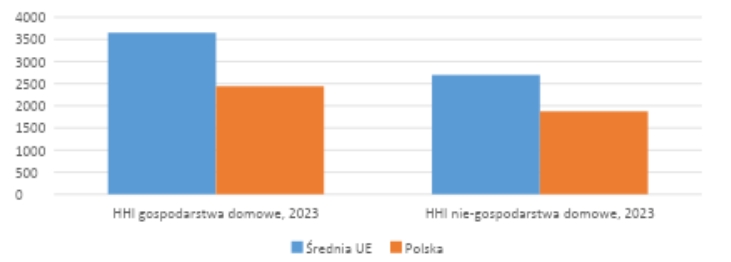

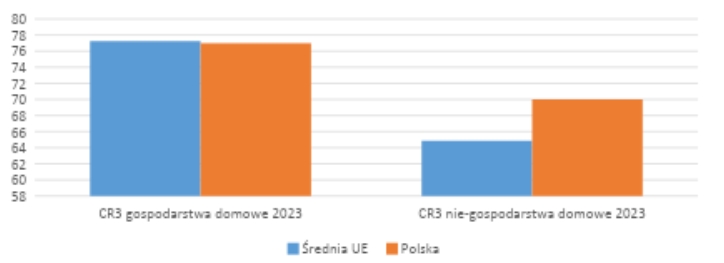

Market concentration in the electricity sector—both for household and non-household customers—falls within the European average. The Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) places Poland slightly below the EU average, while the CR3 index (the combined market share of the three largest firms) positions Poland slightly above it.

Figure 10. Electricity market concentration in Poland compared with the EU average, measured by the HHI Index. FOR’s elaboration based on the ACER–CEER report

Figure 11. Gas market concentration in Poland compared with the EU average, measured by the CR3 Index FOR elaboration based on the ACER–CEER report

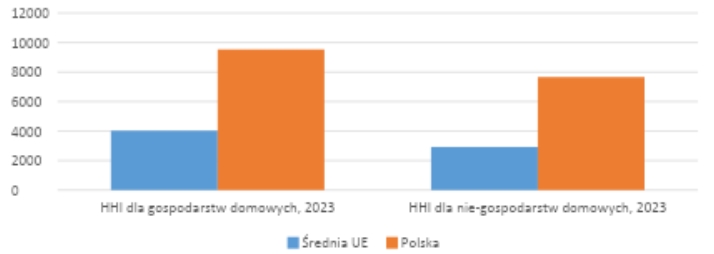

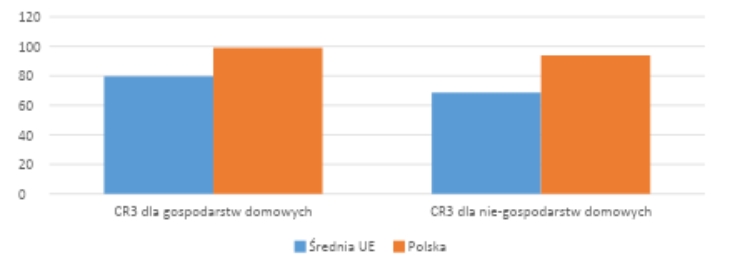

The gas market looks entirely different. Here, market concentration in Poland—both for household consumers and for other customer groups—deviates sharply from the EU average. Both the HHI and CR3 indices a monopoly-level concentration. Moreover, in the case of the household segment, only Hungary (10,000) and Lithuania (9,967) record higher HHI values. For the non-household market, only Malta (10,000) shows a higher level of concentration measured by HHI.

Figure 12. Gas market concentration compared with the EU average, measured by the HHI Index. FOR’s elaboration based on the ACER–CEER report

Figure 13. Gas market concentration in Poland compared with the EU Average, measured by the CR3 Index. FOR’s elaboration based on the ACER–CEER report

Conclusions

The Polish energy sector, in comparison with EU Member States, is characterized by a very high degree of state ownership. State-controlled enterprises dominate every subsector, both in electricity and in gas. Relative to the countries analyzed—including EU states and the United Kingdom—this situation is exceptional. Even in France, with its highly nationalized system, there is a significant private player in the market: TotalEnergies. By contrast, the British and German markets display a far greater degree of private-ownership. Claims that the energy sector’s specificity makes state ownership inevitable should therefore be rejected. It is, purely and simply, a matter of political choice.

The concentration of the sector in state’s hands is also reflected in competition indicators. While the electricity sector is currently around the EU average in terms of concentration, Poland’s gas sector is among the most concentrated and monopolized in the European Union. It is also worth noting that, in electricity, much of the past decade was spent undoing the effects of the ownership policy pursued by the Law and Justice government in 2015–2019. Only last year did concentration levels in electricity generation return to those met in 2016.

Statistical data show that a more decentralized and privatized energy sector is indeed possible. The current state-dominated model could be successfully replaced by more efficient alternatives.

Written by Piotr Oliński and Eryk Ziędalski.

Continue exploring:

Total Defense in Europe: What Is It and Why Do We Need It? with Helena Quis [PODCAST]