At first glance, the beginning of 2017 did not bring any significant changes in the Hungarian politics. Fidesz still leads confidently, having almost an absolute majority. Moreover, power relations between the liberal-left parties are stable. However, we may also notice a number of new tendencies.

A year before the election, the number of voters without declared party preference is decreasing. While in January, 45 percent of the respondents could not choose a party. In March, only 38 percent were uncertain. There are several possible reasons for this tendency. First, a new party (Momemtum Mozgalom) appeared on the political stage. Second, at the same time other parties of the opposition were intensively trying to appeal to uncertain voters. The voters started to look for parties to support, whereas the parties started to campaign to gain the support.

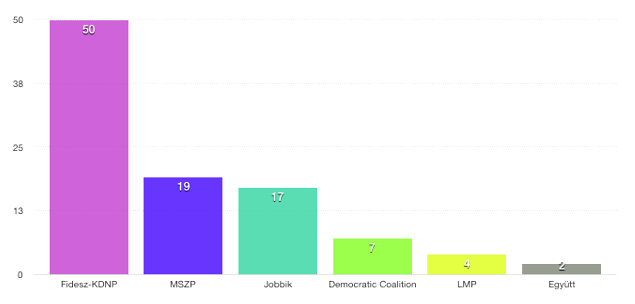

Fidesz still holds a substantial advantage over other parties. Despite the fact that in March it lost 2 percent of support, the government party is still supported by 49 percent of the voters, and it has been on the brink of absolute majority since August. The reason for this could be the credibility problems of MSZP and the consolidation of Jobbik, which involves dispensing with its radical image. However, in the past few weeks, there are more issues (Lex Heineken, or the regulation of the CEU) that could trigger a fall-out in society, even among their voters.

The fall of Jobbik continues. While in November the support for the party amounted to 21 percent, in March it is only 15 percent (among those who were able and willing to identify a party of their preference).

Since the quota referendum in October 2016, the radical Hungarian party could not find a stable political position, which also affected its popularity. Now, Jobbik holds the third place on the political scene in the country – after Fidesz and MSZP. Not being a leader in any topic, the radical party could not compete with Fidesz or the left-liberal parties. Recently, only internal conflicts could generate some media attention for the party.

MSZP became the second strongest party. The rise of Botka László with his new political program brought a whiff of fresh air to the party. As a result, MSZP took over Jobbik two months in a row. It has also become the strongest party on the left-liberal spectrum. With 17 percent of support, MSZP has as many voters as all other left-liberal parties together. However, the question is whether Botka can use his position to effectively gain the support of those parties.

Democratic Coalition (DK) observed an increase in the support by 1 percent. In the past six months, DK was at the level of 5 percent. According to our research, 6 percent of the Hungarian voters support Ferenc Gyurcsány’s party. This means that DK can probably run in the election on its own and might win some seats in the Parliament next year. Since Gyurcsány is a persona non grata for other opposition parties, this strategy seems to be the only way forward.

LMP enters into 2017 in a similar manner that it ended 2016: the green party scored between 4 and 6 percent – thus is close to the electoral threshold. After having faced some difficulties at the end of 2016, LMP started the year very confidently: in the last two months they maintained the support at 5 percent. It seems that after former Co-President of the party András Schiffer left the group, the party has found a way to reach the electorate with the NOlimpia campaing and the referendum initiative on the Paks nuclear power plant.

As far as the small left-liberal parties are concerned, we can observe a stable situation. The first quarter of 2017 did not bring any change in their support. Együtt was set at 3 percent of support, while Párbeszéd and Liberálisok at 1-1 percent since January. Since they do not want to form an alliance with other parties, all the three left-liberal parties are unlikely to enter the Parliament after the 2018 elections. Péter Juhász, the Chairman of Együtt, proposed a strong cooperation and a possible alliance between Együtt, Párbeszéd, LMP, and Momentum, but the latter two refused it immediately. However, without collaboration, they will probably not able to reach 5 percent of voters’ support.

During the analyzed period, a new actor appeared on the Hungarian political scene. The Momentum movement entered the politics with the NOlimpia campaign. The young party recorded 2 percent of support in March 2017, so it has already reached a similar level of popularity as the abovementioned small left-liberal parties. It is unknown however whether these voters came from other parties of from the uncertain camp. However, since Momentum does not want to cooperate with other parties, it will have to gain notable support on their own. Whether the movement can achieve its goal after the end NOlimpia campaing remains to be seen.

In March, Republikon’s survey showed the following trends. Fidesz dropped 2 percent to 49 percent. Just like in February, MSZP follows with 17 percent among party voters. After the socialist party, the third position holds Jobbik. The radical party boasts 15 percent of party voters. DK and LMP would reach the electoral threshold if the elections were to be held next Sunday: Gyurcsány’s party enjoys 6 percent of support, the green party – 5 percent. Együtt still scored 3 percent, while the newly formed Momemtum (thus measured by Republikon for the first time), stands at the 2-percent level and as such the movement could threaten other small left-liberal parties. MLP and Párbeszéd both recorded 1 percent of support.

In March, Republikon’s survey showed the following trends. Fidesz dropped 2 percent to 49 percent. Just like in February, MSZP follows with 17 percent among party voters. After the socialist party, the third position holds Jobbik. The radical party boasts 15 percent of party voters. DK and LMP would reach the electoral threshold if the elections were to be held next Sunday: Gyurcsány’s party enjoys 6 percent of support, the green party – 5 percent. Együtt still scored 3 percent, while the newly formed Momemtum (thus measured by Republikon for the first time), stands at the 2-percent level and as such the movement could threaten other small left-liberal parties. MLP and Párbeszéd both recorded 1 percent of support.

One year before the parliamentary election, the Hungarian parties have just started their first campaigns, which could trigger some radical changes in their positions. At the moment, Fidesz is still leading. However, it is not sure if the party is able to form a government in 2018 on its own. Jobbik and MSZP compete for the second position in the race. As regards the small parties, the real question is whether they will be able to reach the 5 percent threshold. It also remains to be seen whether these parties will decide to form any alliances after all or will run separately. According to the data from April 2017, 5 parties could in the end get into the Parliament. Nevertheless, much can change in a year.