We are witnessing a crucial moment in European history in which « Islamic question » becomes a decisive element, a master symbol of difference in debating identities and setting political agendas. A cluster of different problems in nature, namely the recent refugee crises, jihadist terrorism, and Muslim migrant minorities, are amalgamated together as making part of an “Islamic” problem.

The fusion between these very different categories of people, refugees, terrorists and Muslim migrant citizens in spite of differences in their historical trajectories lead to the reification of Islam, deprived of human visages and real life situations. Islam becomes the master marker, the common assignation for different social groups without distinction but also the ingredient for setting the agendas of politics. Security politics to prevent terrorism, humanitarian aid for refugee crisis, and neo-populism against muslim visibility in public life are all determined and reframed in relation to Islam. Politics of securitization targets “radicalization” of faith in France. Refugees are selected according to their religion. And the neo-populist movements lead in many countries of Europe, defense of Christianity against “Islamic invasion”.

Islam in a paradoxical way becomes an activator of Europeanization. Europe is not a mobilizing political topic around which citizens engage in debating the future of their societies. European Union does not seem to have the capacity to assemble citizens of different nations and provide a sense of belonging. People turn away from discussions concerning Europe. Islam on the contrary, represents a red fiery zone for European publics, provokes controversies and scandals, mobilizes collective passions, and gives voice and visibility to those who enter in that zone. Actors, whether they represent or contest Islam, become audible in determining public controversies, and setting political agendas.

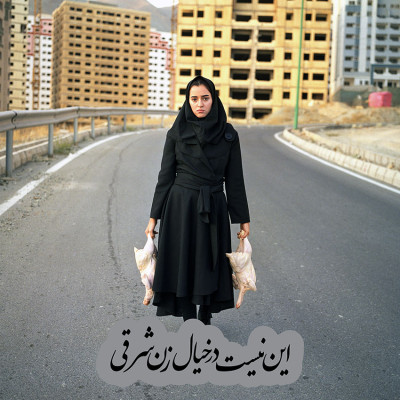

In spite of the differences among European histories of immigration and State politics, there appears a convergence of national responses in framing the Islamic question. We can stress the differences between politics of integration and waves of migration, colonial backgrounds, French republicanism and British multiculturalism. However, in the post-migration period, namely in the process of integration of migrants of second and third generation, Islam becomes the common denominator among muslims of different national backgrounds, ethnic origins and signifies the end of ethno-religious identities of migrants. To the extent that migrants define themselves as “muslims”, it implies distancing themselves from national cultures of their parents and encompassing a more universal sense of Islam in European cultural landscape. We observe the visibility of Islam in public life, the recurrence of cultural controversies around the headscarf issue, mosque constructions, halal food, visual representations of Islam. We also observe the repetition of leitmotifs, their circulation from one national context to another. We see different countries converge in their ways of framing the Islamic question, of learning from each other. Headscarf and burka ban in France becomes for instance a reference for discussion in different national contexts.

The controversies around Islam also changes our mental map of Europe dominated by countries of immigration, France, Germany and Great Britain. The minaret referendum in Switzerland, the cartoon controversy in Denmark enters as landmarks in European debates. From the prism of debates around Islam, a new mapping of Europe is underway.

European liberal democracies have framed pluralism by means of politics of multiculturalism and recognition of minority religious rights. However we witness during the last three decades that both frames are falling short in addressing Muslim difference in Europe. The declaration of the “end” of multiculturalism, and its inadaptability to the question of Islam became a widely accepted conviction. It meant for many cultural relativism, and letting the patriarchal, traditional elements of oppression within the communities intact. For critiques of multiculturalism the lack of interaction between different communities not only led to cultural clashes, but is also a potential enclave for radicalization and terrorism.

European liberal democracies have framed pluralism by means of politics of multiculturalism and recognition of minority religious rights. However we witness during the last three decades that both frames are falling short in addressing Muslim difference in Europe. The declaration of the “end” of multiculturalism, and its inadaptability to the question of Islam became a widely accepted conviction. It meant for many cultural relativism, and letting the patriarchal, traditional elements of oppression within the communities intact. For critiques of multiculturalism the lack of interaction between different communities not only led to cultural clashes, but is also a potential enclave for radicalization and terrorism.

The discourse of religious rights does not seem to provide a satisfactory answer and facilitate the recognition of muslims claims. The islamic covering of women and halal food illustrate the ways in which these debates join “right discourses”, but not religious rights. Islamic veiling is not framed as a religious right but considered to be in contradiction with women’s rights. Similarly halal food, as it has been the case for casher food, is not qualified as a right for minority religion, but raised as an issue of animal rights because of ritual slaughtering. Consequently each controversy around Islam is framed within a discourse of incompatibility between Muslims and Europe, as the manifestation of “clash of cultures”. The pillars of European culture are defined around secular values of Europe, gender equality, right for sexual minorities and freedom of expression. The debates on muslim presence lead to a cultural and social fraction within Europe, to politics of identity, to definitions of “us” and “them”.

Media plays a crucial role in amplification of the clashes as it contributes to the exacerbation of differences, polarization of debates and pursuit for scandals. The neo-populist movements are not the old xenophobic movements of the far right but surf on this common ground of cultural clashes and turn it into politics of enmity with Islam. To the extent they endorse politics of fear of Islam, defend ethno-nationalism against effects of migration and globalization that they join “mainstream” trends and gain popularity. Liberal democratic movements loose ground while Eurosceptic nativism spreads out. In difference from nationalism of universal values and rights, nativism stresses cultural particularism and a sense of belonging with racist connotations, namely the autochthones against “strangers”.

This is the present context in which European publics and politics are refashioned in their confrontation with Islam, amalgamating citizenship claims of Muslim migrants living in European countries, humanitarian aid for the refugee flows from the Middle East and the need for security politics in face of global jihadist terrorism.

In difference from refugees, muslim migrants’ historical and personal trajectories are in European countries, they are in a process of integration and the second and third generation youth do not want to be referred by their migration “background” (“issue de l’immigration”), nor by the national origins of their parents (namely as Algerians, Turks, Moroccans). Muslim claim for visibility in public life is a post-migration phenomenon. They feel they belong to the countries in which they are raised, and in difference from global jihadists, they aspire to participate to the societies in which they live by means of education, professional life and politics. Many follow an itinerary of successful integration, and represent formation of new middle classes. They do not fit to the narratives of “failure of muslim integration”, living in “problem zones”, namely prisons, suburban areas. They aspire for social intermingling and quest ways of combining their religious faith with their desire of participation. They are “ordinary muslims” to the extent that they want to be part of daily life in different cities of Europe, going to school, praying, eating halal etc. However their religious norms, and their visibility as muslims create an obstruction for their recognition as ordinary citizens. They are not considered as acceptable citizens, in conformity with majoritarian public norms.

Muslim presence in Europe challenges the idea that religion should be a private matter. However religious faith has an incorporated personal dimension as well as a public one. It is not only about an abstract faith, but also a ritual, a daily practice, providing a way for surveillance of faith, an incorporated act, source of self-discipline and guidance in modern life. It is a learned practice, a ritual and a discursive practice, learned in private and in collective. There is a hiatus between the subjective meanings that muslims attribute to their faith and the public perceptions of Islam. Living one’s religion in public is perceived as an aggressive assertion of difference and rejection of prevalent values. We can speak of an intercultural miscommunication, something that is “lost in translation”.

Islam becomes a marker of distinction; it empowers muslim actors, provide them with discursive practices, discourse of rights, claims of visibility, and opens up new opportunities. It has a transformative and expansionist effect in domains, from public life, to markets, art and fashion. There is an ongoing process of creative accommodation, a stylization of islamic halal life styles. The debates around burkini, halal jambon, inclusive mosque (mosques for sexual minorities) are among the many examples that illustrate the ways in which islamic ways of life are reinvented within the european cultural landscape.

How to reverse the clash of cultures into an opportunity for elaborating common norms in an intercultural setting, creating new forms of living together, and restoring a civic public culture? Only an inclusive public sphere, pacified from violence, releasing the potential for creating collectively new patterns as in carpet interweaving can be a way for setting democratic agendas.