Besides the general turnout and results of the elections Republikon Institute took a deeper look into the performance of each parties as well, with special regard to the changes since 2010, the parties different performance in different regions and the phenomenon of fragment of ballots.

FIDESZ’S PERFORMANCE

Fidesz-KDNP received almost 2.14 million domestic votes, which together with the letter votes and out-of-the-country ballots amounts to 2.26 million party list votes. This represents 44.87 percent of the votes cast, with which the party alliance gained 133 parliamentary mandates – in other words, they received a two thirds majority again. They lost 564 thousand voters, but by providing citizenship and with it, voting rights for the Hungarians living outside the borders of Hungary, the alliance “regained” 120 thousand voters. Having all this in mind, although Fidesz-KDNP did worse than four years ago, they still managed to reach qualified majority in the Parliament again.

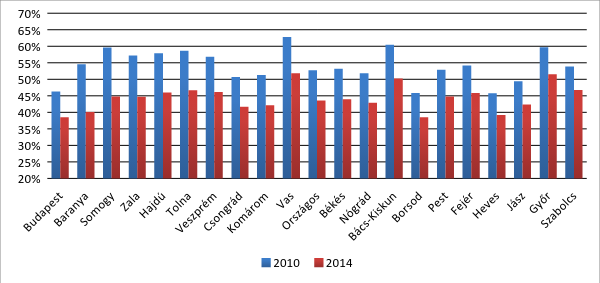

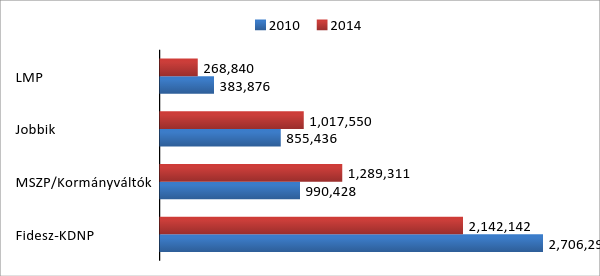

Domestic party list votes in 2010 and 2014

The Fidesz-KDNP party alliance won 96 out of 106 single-member constituencies, thanks to convincing advantage on the national lists and the two-sided opposition. Fidesz-KDNP’s performance was worse than expected in certain counties, weakening to a greater extent than the national average. This primarily affects certain counties in western Hungary: the worse performance does not for the time being endanger the advantage of Fidesz-KDNP, but it caused several wins for the left wing in single-member constituencies.

Figure 3: Fidesz-KDNP party list county results in 2010, 2014

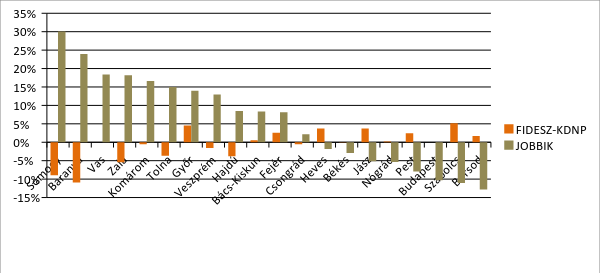

Differences by counties in the change in the support of parties

It is clearly visible that Jobbik shows a far greater regional fluctuation: it strengthened to different extent on a national level. Similarly, Fidesz-KDNP’s weakening is not homogenous either: it weakened to a larger extent in Somogy and Baranya counties, while it weakened to a lesser extent in Heves or Jász-Nagykun counties. Though county data do not allow us to draw unambiguous conclusions about voters’ behaviour, the proportions of Somogy-Baranya-Zala counties indicate that here Jobbik – at least partly – strengthened at the expense of Fidesz.

MSZP-Együtt-PM-DK-Liberálisok’s performance

The five-party left wing alliance received about 1.3 million ballots, based on which it gained 38 parliamentary mandates, which is 19 percent of the seats. The left wing alliance achieved good results primarily in big city districts: its performance was by far the best in Budapest, but characteristically it achieved the strongest results in county seats and their surroundings. Parallel to this it fell to the third place, losing to Jobbik, in the suburban-rural area. The results of the Election 2014 show a twofold process: namely, in certain eastern Hungarian counties the left wing alliance performed better than in 2010, strengthening its second place.

Parallel to the above, western counties in Hungary show a similar approximation, but in a different order. Namely, in these counties Jobbik came closer to the left wing’s results, but without being able to do better than the third place.

The left wing opposition parties have unequivocally reached the best results in the capital: out of ten single-member constituency wins, eight were in the capital; the difference in the number of votes cast on the two alliances was the smallest in the capital (38.5% Fidesz-KDNP, 36.7% MSZP-Együtt-PM-DK-Liberálisok). It should also be mentioned that the result in Budapest was far stronger than the national average.

Jobbik’s performance

Similarly to the left wing party alliance, the extreme right party Jobbik has expanded its electorate, crossed the 20-percent threshold on the national list and increased the number of voters to one million from 855 thousand in 2010. With this, Jobbik gained 23 parliamentary seats in the new 199-seat Parliament: this is 11.5 percent of the mandates. After the election in 2010 the radical party gained 12.2 percent of the seats: though it expanded its electorate, it will have less impact than in 2010 and remain the third largest fraction. Despite achieving better results at the election, the difference between Jobbik and the left wing alliance actually increased: in 2010 there were 135 thousand votes between MSZP and Jobbik and this year the five-party alliance received 270 thousand more votes. It is true, however, that Jobbik strengthened in several eastern counties, and positioned itself in the second place behind Fidesz-KDNP in the suburban-rural area, too. The party’s previous stronghold in Northern Hungary seems to have become more unbalanced and it owes its expansion mainly to the results achieved in western counties. In these western counties the Fidesz-KDNP has weakened more than on the national average and the left wing alliance remained stable. This also means that while in 2010 Jobbik won over former MSZP electorate, in 2014 it was mainly supported by ex-Fidesz voters. The competition between Jobbik and the left wing affected the whole country in 2014. Due to regional levelling and moderate expansion, the radical party was not able to win in a single-member constituency (as opposed to MSZP-Együtt-PM-DK-Liberálisok candidates), but managed to precede the left wing candidate in 41 out of 106 districts. Since in the national total the MSZP-Együtt-PM-DK-Liberálisok party list reached a better result by almost 5 percent, they scored better in the majority of single-member constituencies, too. The national advantage and regional differences lead to a MSZP-Együtt-PM-DK-Liberálisok win not only in a larger number of places, but also, in most cases, to a win with a greater difference preceding the Jobbik candidate, than the other way round.

The ordering, however, shows that there is a serious regional division between the good results of both parties: among the twenty strongest Jobbik constituencies 18 are in eastern Hungary; while among the twenty strongest left wing constituencies, 18 are in Budapest. The other clearly visible difference is that while MSZP-Együtt-PM-DK-Liberálisok characteristically won over the Jobbik with a larger proportion of ballots in county seats and big city districts, the radical party’s candidates mainly won over the left wing candidates in small town and rural districts. It is not independent from these suburban-rural areas to show worse economic performance, with the number of unemployed as one of the most important index for the voters. There is a clear and unambiguous correlation between Jobbik’s performance and unemployment: where unemployment is lower, Jobbik performed worse. In other words, where the majority of people works, the radical party did not perform as well.

Jobbik’s individual constituency results and the employment index of the district (Based on census in 2011)

LMP’s performance

For green party, LMP reaching the five-percent threshold is an unambiguous success: most public opinion polls agreed in claiming that Schiffer’s party, surviving a half-term split in the party and losing the fraction, shall barely get into Parliament. LMP in the end superseded the five-percent threshold by several thousand votes, so it may form a fraction with five representatives. The party received 5.3 percent of votes and barely 2 percent of seats: due to the new electoral system, LMP is the party to have the worst proportional index since 1990.

LMP managed to get into the Parliament despite a significant weakening: the 383-thousand electorate in 2010 decreased to 263 thousand in 2014. This is a more than 30 percent loss, larger than what Fidesz-KDNP endured. LMP gained the most votes in the capital this time, too, but while in 2010 this meant it is the third strongest party, this year it was enough only for a fourth place, following Jobbik.

Votes cast on party lists and single-member constituencies

When looking at the party list and single-member constituencies, we see that the proportion of divisive votes significantly increased among LMP voters (compared to other parties and party alliances): almost ten percent more voters cast ballots on the party’s list than on its individual candidates. The reasoning behind this phenomenon is that the voters wanted LMP to get into the Parliament, but when voting for the individual candidates, they prioritised other criteria. To answer the question as to which individual candidates were chosen by the voters who voted for LMP on the party list, we may draw conclusions from the polling station data – but precise answers may only be given with the help of public opinion poll and asking the voters themselves. Budapest data however provide evidence that a fragment of ballots was cast on the candidates of the left wing alliance.

Different of votes cast on party lists and single-member constituencies, by single-member constituencies (number of votes)

If we look at actual numbers of votes, we still see that the advantage of left wing candidates is in line with the “missing” LMP votes: in the districts of the capital therefore – especially where there was an Együtt-PM candidate as well – those who voted for LMP on the party list, chose a left wing alliance candidate in single-member constituencies.