As life-expectancy has increased during the past decades, governments around the world are trying to figure out a sustainable retirement-income regime. These regimes vary significantly around the world. While some countries put the whole burden on private pension funds, other nations consider the retirement-income regime as a public good.

Nevertheless, in any case there are only two contributors – an employee and an employer. In a public debate, we can usually hear the voice of employees through the labor unions or government channels, however, the voice of employers is systematically missing.

The major institutional aspects of a pension system are whether it runs as a ‘Pay as you go’ (PAYG) or a fully funded system and whether it is publicly or privately managed.

For example, a publicly managed PAYG works in the Czech Republic. Employees and employers contribute 6.5% and 21.5% (decided by the government) respectively from the employee´s gross monthly wage. At the same time, this amount is redistributed to eligible beneficiaries.

On the other hand, a privately owned fully funded pension system is used in Chile. Employees obligatorily contribute 10% of their gross monthly wages to the pension fund of their choice. An employer does not have to contribute at all. This money is held in the individual account until the retirement age. However, the system is subject to change due to current negotiations in the government.

From the 1990s a world trend of pension reforms aimed at transforming the state managed PAYG system into the private pension funds.

Since 1992, there have been more than 110 countries that have undertaken some minor adjustments to their existing systems and about 20 countries that have performed major adjustments in the sense of adopting new systems or replacing their old regimes.

Since the 1995 Pension Insurance Act, the architecture and principles of the retirement-income system have not been significantly changed in the Czech Republic. The Czech system is based on mandatory contribution, which consists of an earning-related component and a basic, flat-rate component.

However, given the current demographic and labor market trends – as (OECD, 2020) states in its study (p. 14):

Population ageing is accelerating in the Czech Republic at a similar pace as the OECD on average. Over the last 40 years, the old-age to working-age ratio – the number of people older than 65 years per 100 people of working age (20 to 64 years) – increased by a little more than 40% in the Czech Republic from 24 in 1980 to 34 in 2020.

By comparison, the old-age to working-age ratio for the OECD on average rose from 20 to 31 over the same period. Over the next 40 years, it will rise in the Czech Republic by more than 75% to a projected 60 in 2060 (against 58 for the OECD on average). This rapid shift in the demographic structure is the result of rising life expectancy and low fertility rates’, there is a significant demand for a systematic pension reform.

The Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs has founded the Commission for Fair Pensions (2019) to lead the discussion on the system changes and its sustainability.

However, as being an extremely important political topic, the debate is very much focused on the position of the state budget and position of employees (voters). A view of employers is systematically missing. Recently, a few outcomes of the Commission´s debates have been published. Basically, the new system should consist of Pillar 0 and Pillar 1.

The goal of the Pillar 0 is to provide an equal retirement-income to all retirees, while Pillar 1 is meant to consider the previous life experience a traditional point of view (an amount for working career and an amount for not work-related activities).

The reform suggests creating a virtual individual account for each beneficiary which should be as transparent as possible. On the one hand, the new reform covers the expense side relatively well. On the other hand, the reform completely misses the plan how to finance the retirement-income scheme.

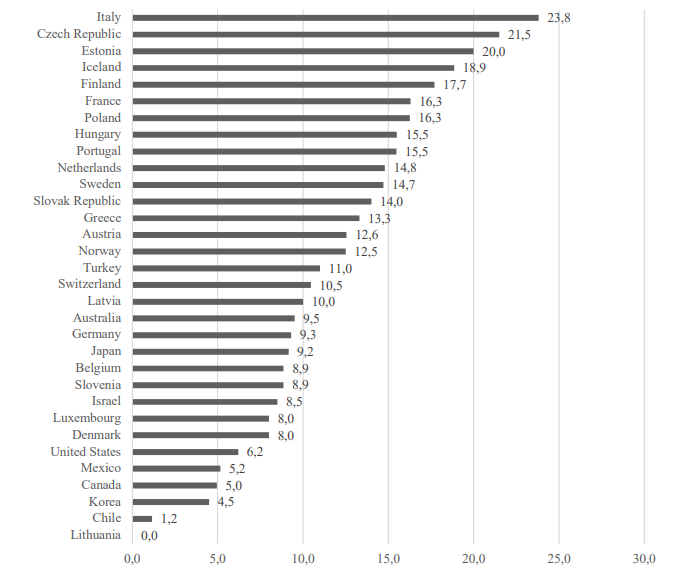

The following figure gives an overview of an employer contribution into the actual pension systems in OECD countries (public or private). Independently of the ownership of the pension system, this contribution plays a significant role in the cost of labor, especially in Italy, the Czech Republic, and Estonia.

On the contrary, Chile has one of the lowest contributions from the employer´s side.

Figure 1: Contribution of an Employer either to a Public or a Private Pension System (2018 data)

Source: OECD 2019, Pension at Glance (derived from Table 8.1)

Source: OECD 2019, Pension at Glance (derived from Table 8.1)

(OECD, 2019) summarizes a few recent reforms related to the employer’s contribution. For instance, Hungary reduced the pension contribution rate paid by employers from 15.75% in January 2018 to 12.29% in July 2019.

Lithuania offers a very interesting case; it has shifted social security contributions from the employer to the employee. The employer’s contribution rate was reduced from 31% of monthly payroll to 1.5%, and the employee contribution rate rose from 9% of monthly earnings to 19.5%, while the remaining shortfall will be financed by taxes.

Consequently, the earnings ceiling is slowly lowered from 10 times the average wage in 2019, to 7 times in 2020 and to 5 times from 2021. Finally, Germany set new minimum and maximum pension contribution rates.

Consequently, the total contribution rates cannot rise above 20% or fall below 18.6% by 2025, while before the maximum contribution rate was supposed to be 20% until 2020 and 22% from 2020 to 2030.

The effects of a pension reform on employees have been vastly studied, but less is known about the impacts on employers. For instance, a pension reform introducing the changes in pensionable age could have significant impacts on the composition of the employer’s workforce (Berg et al., 2019).

Increasing the retirement age may influence the company´s profitability directly through labor costs and indirectly through possible productivity effects. Similarly, as (Berg et al., 2019) claims, shifts in the labor force participation of older workers due to pension reform may change the composition of the workforce in a way that affects company´s performance and results in the risk of downsizing.

As the administrative data from German social security notifications between 1990 and 2010 show, downsizing is more likely in companies where the reform leads to a larger share of workers over the age of 58.

In conclusion, the demographic change demands quite substantial reforms of the PAYG pension system. The Czech Republic is not an exception.

However, according to the outcomes of the Commission for Fair Pensions there is still a room for new proposals, especially in terms of financing the pension system. When considering the current reforms and experience from abroad, a mix of a public and a private system provides a solid base not only for a sustainable pension system but for employers as well.

References

Berg, P., Eckrote, M., Hamman, M., Hochfellner, D., & Piszczek, M. (2019). Pension Reforms and their Implications for. In American Economic Association.

OECD. (2019). Pensions at a Glance 2019. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/b6d3dcfc-en

OECD. (2020). OECD Reviews of Pension Systems: Czech Republic. In OECD Reviews of Pension Systems, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1787/e6387738-en.

Written by Matěj Opatrný

The author cooperates with the Center for Economic and Market Analyses (CETA Czech Republic). The project dealing with a research of employers’ perspective was supported by the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom

Continue exploring:

Will Tax Brake Protect Citizens’ Wealth in Slovakia?

Position Paper on Proposal for Directive on Adequate Minimum Wages