It will soon be two years since rock rebel Javier Milei took office as president of Argentina. Since then, Argentina’s economy has been shaken to its foundations. In a country with a deep-rooted public finance crisis, hyperinflation, and extensive subsidies, a government of uncompromising cuts took office and, within a few months, changed the fiscal balance, suppressed inflation, and reduced dependence on social transfers. Milei’s shock therapy remains the subject of heated debate even after less than two years, but its effects cannot be overlooked.

And Inflation Again

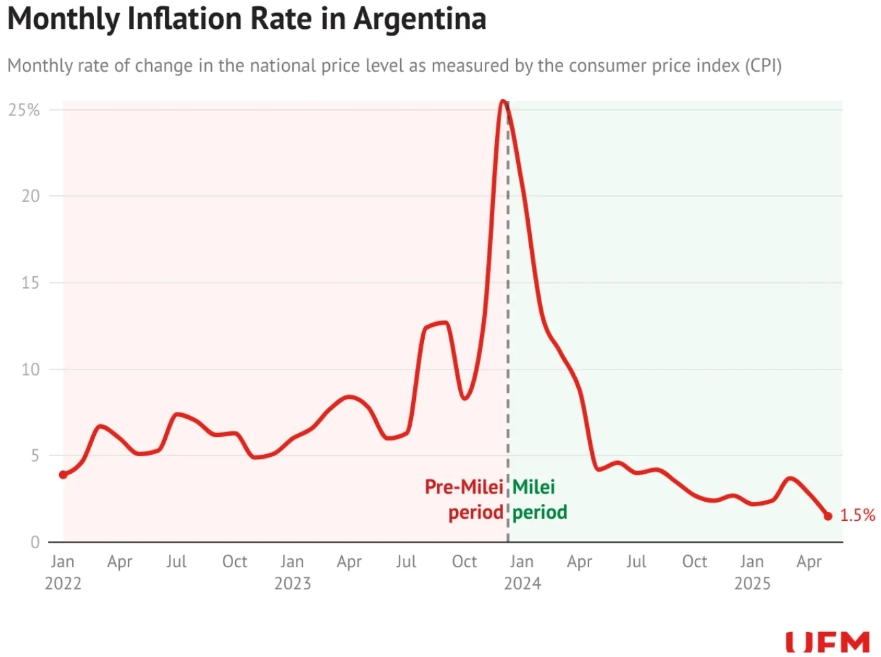

In Czechia, we certainly still have vivid memories of the period of high inflation, whose harmful effects on the state budget, entrepreneurs, and ordinary citizens need no lengthy explanation. However, Czech inflation is only a pale shadow of Argentina’s. While in Czechia, the average annual inflation rate reached a record high of 15.1% in 2022, Argentina had to contend with inflation of 25.5% relatively recently, but on a month-on-month basis! It is no wonder that inflation was the biggest bogeyman for most Argentinians.

This makes the latest data from May 2025 all the more encouraging, according to which month-on-month inflation (showing how much consumer prices have changed compared to the previous month) fell to 1.5%, which is an exceptionally high figure by Czech standards, but a phenomenal result in Argentina, as monthly inflation last fell below 1.5% in November 2017. If we also look at the average monthly inflation over the last 10 years, the average is 4.4%.

Fiscal Diet

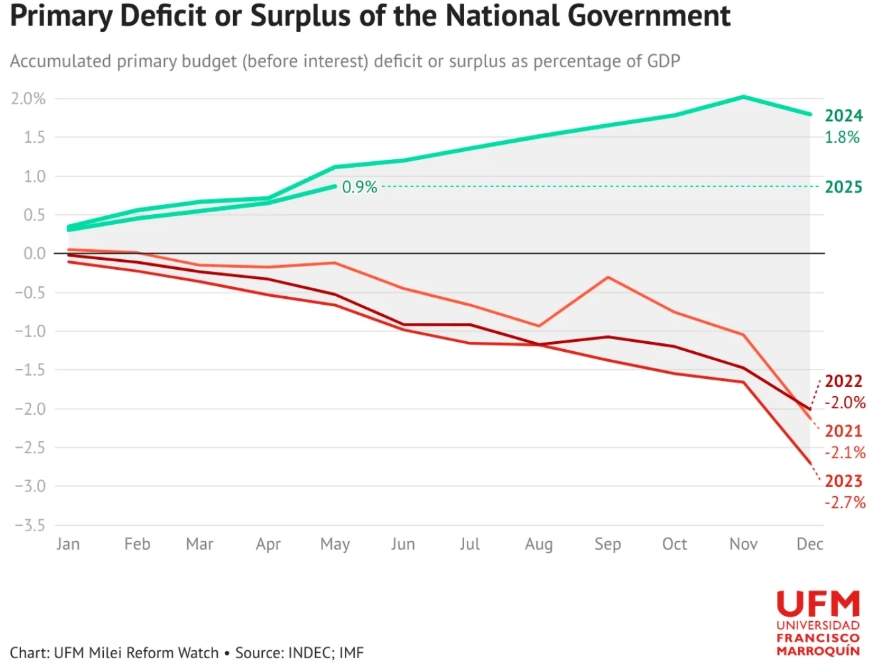

The path to Argentina’s recovery also lies in fiscal restrictions. Overall, Argentina is experiencing a golden age in terms of fiscal discipline. In terms of the primary balance, i.e., the balance excluding interest (and excluding the consequences of previous governments’ economic policies), the budget moved into the black immediately after Milei took office.

Much attention is being paid in Argentina to subsidies, which accounted for 1.43% of Argentina’s GDP before the Argentine libertarian took office in 2023 and 0.97% in 2024. Specifically, subsidies for energy and transport were reduced by one-third (measured not in nominal terms but in relation to GDP), and other subsidies (especially subsidies for drinking water and sewerage services) were reduced by less than half.

Fiscal Restrictions And Poverty

From time to time, disturbing reports have appeared in the public sphere that people in Argentina are falling into poverty and that the Argentine administration is insensitively cutting social transfers to the population. First, it must be said that before Milei’s arrival, social spending accounted for 67% of the state budget. Therefore, if fiscal consolidation were to take place, the cuts logically had to affect the area that accounts for two-thirds of the expenditure side of the budget.

Then there is another inevitability—if there are (and inevitably there were) savings in social transfers, logically, some recipients of these transfers will fall into poverty. This is obviously not a pleasant phenomenon, but we can see the destruction that spiraling social transfers lead to… in Argentina.

In the first half of 2024, the poverty rate in Argentina rose from 42% to 53%. However, the second half of the year brought excellent news, with the poverty rate falling to 38%, below the level before Milei’s arrival. If someone managed to reduce the poverty rate in the country by 4 percentage points in a year, it would deserve a nod of approval. But if such a reduction occurs, especially with significant cuts in social spending, it deserves a pat on the back. Argentine family budgets are also encouraged by the revival of real wage growth, which has been falling steadily in recent years.

However, the recovery is not limited to real wages, but also extends to the economy as a whole. In the second quarter of 2025, GDP grew by a remarkable 7.6% year-on-year, and overall growth for 2025 is expected to be 5.2%, followed by 4.3% the following year. If we take a closer look at GDP growth, household consumption should be a major driver, and we are seeing a very interesting development in gross fixed capital formation (investment), which fell by 17.2% in 2024 due to fiscal cuts, but is expected to grow by 29.8% and 15.4% in 2025 and 2026, respectively.

Peso Exchange Rate on Leash

The issue of the Argentine peso exchange rate generally remains somewhat sidelined in public debate. Let’s first look at how the central bank can approach exchange rate regimes. It can be said that the two extreme models of exchange rate regimes are the freely floating exchange rate (the exchange rate is determined by market supply and demand without intervention by the central bank) and a fixed exchange rate (the currency is pegged to another currency, for example, it is fixed that EUR 1 = CZK 24, and the central bank maintains the exchange rate through interventions, i.e., purchases and sales of currency).

If we do not consider the specific system of dollarization (a term generally used for substitution with a currency other than the dollar), there are various “hybrid” variants between these two extremes. One example is managed floating, which is closest to the Czechia model, whereby the regime is formally floating, but the central bank intervenes if it deems it appropriate based on developments.

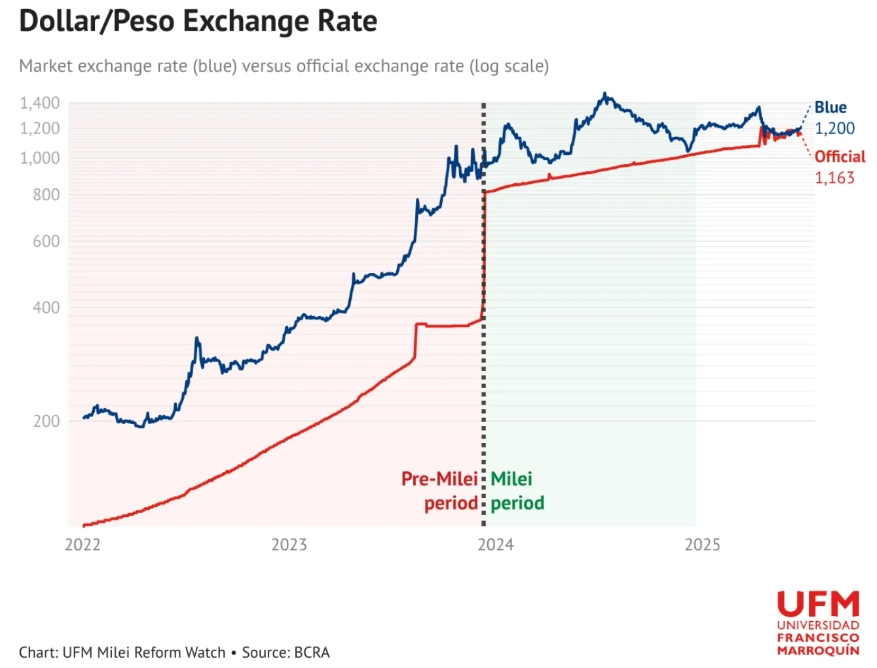

After his election, Javier Milei sharply devalued the peso and introduced a crawling peg, which consisted of devaluing the official (red) peso exchange rate by 2% each month. This system can be seen as a third way between a fixed and a floating exchange rate. Alongside the official exchange rate, there is also an unofficial exchange rate (“Dólar blue”), which emerged in 2001 as a result of tough government restrictions on the use of the dollar in the Argentine economy. Interestingly, the black market is so popular in Argentina that the “blue dollar” exchange rate is regularly published as a parallel exchange rate to the official one.

The crawling peg mechanism created a predictable exchange rate regime after a sharp devaluation by weakening the peso in small, controlled steps. From February 2025, devaluation under the crawling peg regime slowed to 1%.

However, the problem for Argentina arose when the rate of price growth was faster than the administrative devaluation of the peso (crawling peg). In other words, month-on-month inflation was higher than “month-on-month devaluation.” Although this may not be intuitive at first glance, this situation meant a real appreciation of the peso, and Argentine producers were losing competitiveness abroad as goods from Argentina became more expensive, and exports suffered.

Let’s illustrate this with an example:

- in January 2024, the exchange rate was 1 dollar = 1,000 pesos

- Based on a 2% devaluation, the exchange rate in February was 1 dollar = 1,020 pesos.

- However, month-on-month inflation in February 2024 was 13.2%, meaning that the price level in Argentina rose by 13.2% (significantly faster than the exchange rate change).

Let’s consider, for example, that in January, a baguette in Argentina cost 1,000 pesos, which was equivalent to 1 dollar. In February, it cost 1,132 pesos, but the new exchange rate was only 1 dollar = 1,020 pesos. So in February, a baguette cost 1.11 dollars.

The result? Argentine baguettes became more expensive abroad, costing $1.11, even though the peso was nominally weaker. However, the real effect was the opposite – the peso strengthened, which had negative consequences for exporters, especially given that in 2024 Argentina exported more (USD 80 billion) than it imported (USD 61 billion), particularly products related to plant and animal production.

As can be seen from the graph of the dollar-peso exchange rate, Argentina switched to a floating regime after a relatively short period of a 1% crawling peg, a step that Milei’s Argentina needed time to take. One of the problems was the lack of foreign exchange reserves at the Argentine central bank, which would thus have minimal room to “defend the exchange rate” in a situation where there were legitimate concerns about a sharp and uncontrolled devaluation of the currency. A warning sign was Argentina’s transition from a fixed to a floating exchange rate in January 2002, which resulted in the devaluation of the peso within a few months, with the exchange rate changing from USD 1 = 1 peso to USD 1 = 4 pesos, but at the same time, inflation exploded. Logically, Milei needed to avoid this at all costs.

For Milei, this step would mean exposing himself to the risk that households and companies would start to engage in so-called currency substitution (in the broader sense), i.e., they would start to buy up anything that is not in pesos, such as dollars, art, gold, etc., which would put further pressure on the foreign exchange market and thus further weaken the peso.

The weakening of the peso would then mean that goods imported into Argentina from abroad, such as machinery, vehicles, and electronics, would become more expensive (a product costing $10 would no longer cost Argentine consumers 10,000 pesos, but 15,000 pesos, for example). The result would be a secondary wave of inflation. Another risk would be a loss of inflation expectations, as economic agents would likely lose confidence in price stability and begin to “anticipate inflation” through their pricing and wage behavior (known as de-anchoring expectations). Let us remember that all this is already happening in a situation of disproportionately high inflation.

However, we should not think that the crawling peg is a miracle tool. The central bank was forced to burn through a considerable amount of its foreign exchange reserves to defend the official exchange rate. In April this year, however, Argentina reached an extremely important moment – a loan from the International Monetary Fund. Part of the loan was the condition of transitioning to a “new exchange rate regime with greater exchange rate flexibility.” This meant that Argentina abandoned the crawling peg and switched to a managed floating exchange rate within a band, which in practice means that a currency band was set, ranging from 1,000 to 1,400 pesos per dollar, and this band will be widened by 1% each month.

However, the loan from the International Monetary Fund is not just a monetary accounting operation, as it is conditional on the Argentine government continuing with fiscal consolidation and structural reforms, for example.

Another positive indicator for Argentina is country risk, which is one of the main indicators of a country’s credibility on global financial markets. It is the difference between the yield on 10-year Argentine government bonds and the yield on 10-year US government bonds. In other words, the Argentine government must offer investors a yield that is 7.3 percentage points higher than that offered by the US government in order to be able to sell its bonds at all. This is a kind of risk premium that reflects, for example, the risk of default, currency instability (inflation, exchange rate developments), or political risk in the country. The lower this indicator is, the more confidence investors have in the government’s ability to repay its obligations. Although 7.3 is not a satisfactory figure, the downward trend in this parameter is positive.

Written by Jakub Kuneš, Liberal Institute / Centre for Economic and Market Analyses

Continue exploring:

The Return of History to the Present with Luuk van Middelaar [PODCAST]

Winning the Youth: Lessons from Zohran Mamdani for European Politics