Despite the catch-all political campaigns which are aimed to attract all the segments of the electorate, regardless of their gender, the politics still remain in most of the “old democracies” the playground for men. In 2015 the average percentage of women in parliaments in OSCE area was 24.4 percent. This is remarkably low figure considering that women constitute more than half of the electorate and ability to identify with the parties or particular candidates plays a crucial role in voters’ preference formation. Therefore it should be essential for the catch-all parties to have considerable share of women in their membership, voter lists and, of course, in elected bodies to attract the female voters.

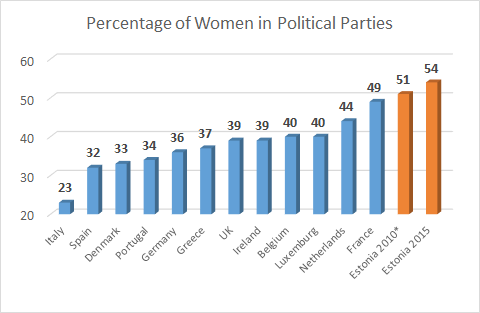

In this category Estonia places among the mediocre countries with 26 percent of women in Riigikogu. Regardless of relatively low share of women in Estonian parliament, Estonia leads the rankings of women percentage in party memberships with 54 percent. This means that women form the majority of the party memberships, but they are not influential enough to have an effect on parties’ policies, electoral lists formation and at the end also on election outcomes.

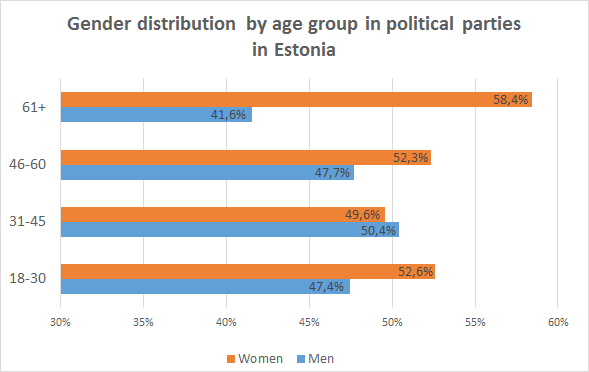

The percentage of women in the party membership is important, but it is also vital to notice in which age group the women belong. Analysing the boards of Estonian political parties, the average board member is between the age of 35 to 50. This means that with some exceptions the older and younger party members do not influence the policy making process as much as the politicians in that age. If women are dominating among the elderly or among the younger and newly joined party members, then it implicates that women are influencing just the gender balance of the parties, but not the real policy-making process.

In Western Europe, the average share of women in political parties is 37 percent. Moreover, the percentage of women is lower in Southern European countries and higher in Western Europe. In this category Estonia holds a leading role with 54 percent of women in the political parties and this share is constantly growing.

Source: Susan E. Scarrow and Burcu Gezgor, “Declining memberships, changing members? European political party members in a new era”, Party Politics, Vol. 16, No. 6, 2010, pp. 823 – 843

Source: Susan E. Scarrow and Burcu Gezgor, “Declining memberships, changing members? European political party members in a new era”, Party Politics, Vol. 16, No. 6, 2010, pp. 823 – 843

Priit Kallakas’ calculations on Estonian Company Register data

The difference in gender composition in political parties between the “older democracies“ and Estonia could be explained by the history of political systems. The parties in Western Europe developed in the times when social norms perceived politics as a playground for men only which already determined the gender balance of the parties. In Estonia, on the other hand, the political class emerged after the collapse of Soviet Union at the beginning of 1990s. This meant that the stigmas which dominated the Western European societies decades earlier were not relevant in Estonia. Newly emerged political class was open to both women and men.

Source: Priit Kallakas’ calculations on Estonian Company Register data

Source: Priit Kallakas’ calculations on Estonian Company Register data

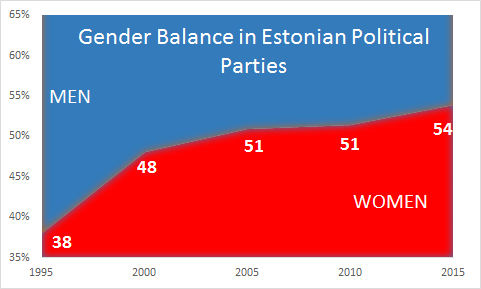

Even though immediately after restoration of independence in Estonia the men formed the strong majority in the political parties, the share of women in politics started rapidly to grow. One cause for it was the positive social attitude towards active women, but even more influential was the demographical aspect. In 1992 the life expectancy for males was 63 years and for females: 75 years.

This 12 year gap in life expectancy is also visible in Estonian party memberships. Within the age group over 61 years, there is 60 percent of women and 40 percent of men. As this 61+ age group is also the largest age group in Estonian parties (30 percent of party members are over 61), it therefore has the strongest influence on the gender composition of the parties.

Source: Priit Kallakas’ calculations on Estonian Company Register data

Source: Priit Kallakas’ calculations on Estonian Company Register data

Third cause why there are more women in Estonian parties than in Western European parties is related to education. Studies have shown that party members tend to be above average in terms of income and education. And if we compare the gender balance among the university graduates in EU and in Estonia, we see that according European Parliament report 59 percent of university graduates in EU are women, while in Estonia this figure is high as 70 percent. Women majority among university graduates has effect to the gender distribution at the age group of the youngest party members as well. In Estonian parties 53 percent of party members under 30 are women and this means that the political parties in Estonia continue to feminize.

In the so-called ‘policy-making group’ aged between 31 to 45, we see that men constitute slight majority with 51 percent of this group. This means that women don’t yet have the majority down the line of all the age groups and party boards are still dominated by men. Therefore we can still say that at the moment women in Estonian political parties dominate the party memberships, but not the decision making process.

To draw conclusions and look into the future of memberships of Estonian political parties we may predict that the women dominance in Estonian political parties continues to grow, firstly because of demographical situation in Estonia especially due to the women’s longer life expectancy and secondly due to women’s dominance among university graduates who are more prone to join the parties. This will also create an identification possibility for other women to step into the politics as they will see positive role models in party leaderships, electoral lists and hopefully also in legislative bodies.