A transition is conditioned on changes to the setup of societies. Europe went through a substantial transition at the end of the 17th century, when liberal ideas and institutions took hold in a sustainable and durable way for the first time in history.

The liberal order started to develop and has continued to exist, with some hiccups along the way, until today, not only in Europe but also in other parts of the world. With the fall of the Soviet Union in 1989, it seemed inevitable that the whole world would follow suit. Postcommunist countries in Eastern Europe, actually, adopted liberal policies quicker than anyone else.

In recent years, however, liberal institutions have been attacked from many sides, especially in Eastern Europe where illiberal reforms have been implemented, the rule of law weakened, the freedom of the press and association curtailed, and economic rights constrained for those not in power.

It is not only in East Europe in which movements have garnered increasing support for replacing liberal institutions at least to some extent. The traditionally liberal Western Europe has also been affected by it, though its institutions have proven more resilient.

Explanations for the increasing unpopularity of liberalism are manifold, including a loss of belonging and identity, breakdown of social institutions, spiritual crises, and political organizations that have excessively centralized political systems.

For liberalism to continue to prevail even after the current political realignment, it needs to make the moral and cultural, less the economic, case for a free world, and take into account that humans are social beings and in need of strong communities and social bonds.

Introduction

The end of history seemed to have been reached when the Soviet Union fell in 1989. The liberal order had finally prevailed over the authoritarian, capitalism over socialism, and freedom over coercion.

The 1990s and the 2000s were dominated by a globalized, extended order based on free trade, multilateral governance through supranational organizations, and the United States as the unrivaled global voice.

Ever since, though, much has changed. As Kolev (2018, 86) writes, “The development of the past years can be characterized as a process of cumulative implosions of order,” as this new and seemingly stable and durable order has been faced with “new fragility” (Ibid., 85).

From the election of Donald Trump as U.S. President and the Brexit referendum, both in 2016, to the rise of new anti-establishment forces in countless countries, including France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Spain, which, some more than others, advocate for illiberal, often nationalist policies, has brought a new dynamic to politics.

In countries like Russia and Turkey, authoritarianism has returned, while other movements in Hungary and Poland are attacking their own liberal institutions. Looking beyond the West, China seems to have abandoned entirely liberalization efforts. Instead, it is focusing on instituting an Orwellian police state (Vlahos 2019).

Thus, the consensus that seemed to have been reached that liberal political systems are the best and most-desired systems has faced significant backlash in recent years.

Instead of a simple backlash to the politics and economics of the last decades, some see a “realignment” (Davies 2018) ongoing, as not only institutions we thought to be durable are suddenly attacked and rethought, but also the topics change that people care about. Instead of economics, cultural and identitarian issues have made a comeback as problems that are discussed in a time when many think that these concepts have lost their meaning.

Is it true that as Davies (2018) writes, “What most developed democracies are experiencing is a realignment of politics”? And if so, where are we heading? To what are we transitioning?

This paper will not provide a definitive answer to these questions. However, it will try to analyze what has happened in recent years in the context of past transitions, take a look at the current situation, ponder about reasons what is happening, and finally – in a more normative ending – present a way of how the liberal order could be saved after all.

Enlightenment Transition

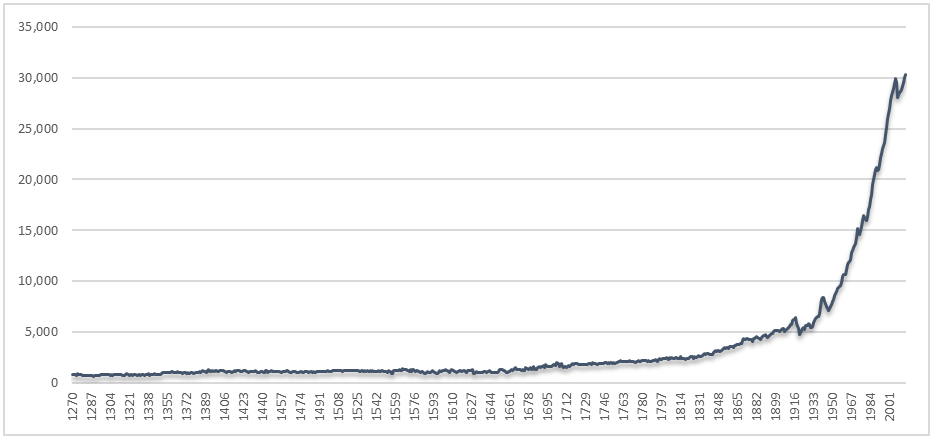

We trace the beginning of the liberal order back to the industrialization. What occurred in the 17th century in Britain and what subsequently spread to many other European nations as well as across the Atlantic has been described by Goldberg (2018, 10) as nothing short of “the Miracle” – not a miracle, but the Miracle. While the industrial revolution was accompanied by many furious responses due to strenuous working situations in factories early on, wealth accumulated rapidly. For all of previous human history, from the hunter-gatherers to Medieval Europe, humans were more or less equally poor (Clark 2007). However, gross domestic product (GDP) in England and the United Kingdom as a result exploded (see Figure 1). As Goldberg (2018, 7) writes, “The startling truth is that nearly all of human progress has taken place in the last three hundred years.”

Figure 1. GDP per Capita in England and the United Kingdom, 1270–2015

Source: Our World in Data 2013

Source: Our World in Data 2013

What was the reason for this sudden spurt in growth, which has since continued, even accelerated, and engulfed much of the world to this day? The reasons for why the industrialization happened is still much disputed to this day.

Some see the reason in the decentralized nature of Europe, which spurred competition between different governing institutions, thus leading to best practices, i.e., liberal institutions, gaining the upper hand over more authoritarian and intrusive practices.

For instance, Raico (2018 [2004]) argues that

“Although geographical factors played a role, the key to western development is to be found in the fact that, while Europe constituted a single civilization — Latin Christendom — it was at the same time radically decentralized.”

The resulting

“’demonstration effect’ that has been a constant element in European progress — and which could exist precisely because Europe was a decentralized system of competing jurisdictions — helped spread the liberal policies that brought prosperity to the towns that first ventured to experiment with them.”

Rouanet (2017) agrees that Europe’s decentralized nature “gave birth to individual liberty.”

Moreover, Röpke (1960, 244) argues similarly in A Humane Economy that “Decentrism is of the essence of the spirit of Europe.”

Others see the Protestant work ethic as the defining aspect of how industrialization was made possible (Weber 2002 [1904]), or that a military revolution transpired at the time (Davies 2019), or that the British historic love for liberty led to the evolution of liberal institutions in England (Hannan 2013).

Meanwhile, McCloskey (2016, XXIII) argues that “bettering ideas, and especially ideas about betterment … drove the modern world.” Thus, for McCloskey, a change in the ideas that were being held was mainly responsible for this overarching change in history.

As such, McCloskey (2010, 390) argues, “change in rhetoric has constituted a revolution in how people view themselves and how they view the middle class, the Bourgeois Revaluation. People have become tolerant of markets and innovation.”

Regardless of what the defining factor was that “enriched the world” (McCloskey 2016), it is clear that the West went through a transition at that point. A transition is not merely economic growth or further development. Rather, it is a process that brings about significant changes to the setup of a society in general.

The transition that happened at that point in history brought forth the liberal order that we cherish so much today. What is this liberal order?

For Goldberg (2018, 8), the liberal order, which he sees most clearly in the “Lockean revolution,” i.e., in the ideas of John Locke – though, one has to add, others have seen ideas that are typically considered liberal already present, and in a more convincing way, in the likes of Aristotle, St. Augustine, and St. Thomas Aquinas (Anderson and George, 2019) – “held that the individual is sovereign; that the fruits of our labor belong to us; and that no man should be less equal before the law because of his faith or class.”

Derived from this definition are three principles. First, democracy, as only in a democracy individual can truly be sovereign – not ruled by some authority which does not at least represent the will of the people in some way – and be equal before the law.

Second, the market economy, as only in a market economy can one have private property and trade it freely. And third, the rule of law, as only with the rule of law would the democratically elected rulers be prevented from doing what they want.

From these first principles, others can be derived, such as freedom of speech and association, a free media, and religious liberty, or self-government by the people and a system of checks and balances set out in some type of constitutional document (Burns 2019).

These liberal ideas would quickly spread around Western Europe and North America, where it perhaps came to full fruition in the United States.

Transition in Postcommunist Europe and Beyond

Liberal principles would take hold of what would become the West: the area of Europe, North America, and other countries heavily influenced by liberal principles, such as Australia and New Zealand. There were collapses of the liberal order once in a while, most notably during the two World Wars of the early 20th century.

However, in general, the liberal order endured, and with it, wealth in these countries continued to accumulate with accelerating pace. The post-war era saw a major rebuilding of war-torn areas, followed by decades in which the West, led by the United States, hoped to prove that liberal democracy was superior to the communist counterpart.

The win for the former came with the fall of the Soviet Union in 1989. The “end of history” was quickly called by some (Fukuyama 1989), and those that disagreed at least thought that with the eventual and evident triumph of the liberal democratic system, we had found the best system imaginable. From here on out, “decline is a choice” (Goldberg 2018, 351).

With the fall of the Iron Curtain, Eastern Europe was liberated from communism and was able to reconnect with the rest of Europe after decades of suffering under totalitarianism. It was clear from the beginning that the primary task of postcommunist countries would be to catch up to the West, not only in wealth but also structurally, both by implementing liberal reforms.

After all, if liberal democracy was the best political system available, then progressively catching up to it would be a natural path, letting Eastern European countries reach the end of history, too.

At first, the catch-up process brought impressive results. At the 25th anniversary of the fall of communism, Shleifer and Treisman (2014, 14) wrote that

“In most postcommunist states, life has improved, often dramatically. Citizens enjoy higher living standards, broader political rights, greater autonomy and personal dignity.”

Indeed, many of these countries quickly became part of the Western international community, joining NATO and the EU, and becoming exemplary models of how to implement liberal reforms around the world.

The transition in Eastern Europe was in such a swing that the traditional West focused on new parts of the world to liberate, specifically the Middle East, where the democratization of the Arab world seemed for many to be inevitable (Beck and Hüser 2012, 4-5). These assumptions proved hasty in the end.

Nonetheless, political systems of several countries, like Tunisia, transitioned into something often akin to liberal democracy. And states like Poland, the Czech Republic, or Slovakia, reached levels close to any other stable Western democracy. It seemed at this point merely like a matter of time until Eastern Europe would join the traditional West as fully liberal democratic regimes.

The Backlash

Instead of an everlasting victory of liberalism, backsliding occurred. While economic growth is still robust and catching up is at least still ongoing in terms of wealth and prosperity (Bayer 2018), many Eastern European countries have seen a rollback of the previous transitional process that introduced liberal institutions to this part of the continent.

“With the rise of nationalism, populism, and hybrid forms of authoritarianism, freedom has been for years under assault in many parts of the world,” including Poland and Hungary, writes Porčnik (2018) in a review of her Human Freedom Index, which shows that many in Eastern Europe enjoy less freedom today than in the past (Vásquez and Porčnik 2019).

It is not a subject of this paper to go into detail about how this happened in each country. Instead, it can be summed up that liberal principles, from freedom of the press and free association to the rule of law and political rights, have been attacked across postcommunist countries.

For instance, in Poland with an attack on the independent judiciary and in Romania with an attempt to abolish charges against corruption.

Meanwhile, Viktor Orbán’s government in Hungary has pursued “the systematic dismantling of checks on political power” (Rohac 2019). Concurrently, free association in Hungary has been constrained by pushing foreign NGOs (Open Society Foundations 2018) and one university out of the country (Redden 2018).

Further, the media landscape has been consolidated around people close to the Hungarian government (Kingsley 2018), while a new economic oligarchy of friends and relatives of Prime Minister Orbán has been high on the agenda (Rohac 2019).

Hungary, as well as the other mentioned countries, are far from being illiberal, fascist states – criticism of the regime can still be openly voiced, and life in Hungary is by and large relatively open and free (Collins 2019). However, the attacks on liberal institutions and principles have been noticeable.

Despite all of this, support for the government in the respective populations is as high as ever. Orbán’s Fidesz is polling around 55 percent with a lead of almost 45 percent to the second place (Századvég 2019). In October 2019, the Polish electorate handed the Law and Justice Party “one of the largest victories in Poland’s democratic history” (Day 2019).

Thus, the question naturally abounds why that is the case: Why would the people that had to live through decades of totalitarianism and subsequently enjoyed the economic, social and cultural benefits of liberalism voluntarily give away this order again for authoritarian features?

Crucial for finding a reason is the concept of “shared mental models,” i.e., the way a group of people sees the world and thinks how the world should be structured. These shared mental models are deeply influenced by cultural, religious, and historical elements, and they will be decisive in how readily accepted will be the introduction of certain ideologies (Zweynert 2004, 1).

Eastern Europe has been less susceptive to liberal ideas and is recently even backpedaling from it because of shared mental models. One argument along these lines is that liberal reforms in postcommunist countries were too rapid and ignored the local circumstances (Marangos 2004, 221).

In contrast, in Germany after World War II, where the shared mental model of the population was also not in favor of capitalism, the introduction of it worked because it was framed in a way in which it was acceptable for the Germans (Zweynert 2004).

Another such argument is that the religious element in the shared mental models is less compatible with liberal principles, leading to the aforementioned backlash. While Western countries, as well as some postcommunist countries like the Visegrad nations, are dominated by Latin Christianity, others, like Russia, Ukraine, Romania, and parts of the Balkans, are dominated by Orthodox Christianity which is less receptive to liberalism due to its holistic worldview (Zweynert and Goldschmidt 2005, 8-9).

While this argument may explain why these Orthodox Christian countries never transitioned to liberal institutions as quickly as postcommunist countries with dominant Latin Christianity, it does not explain, however, why those dominated by Latin Christianity are affected the most by the backlash.

Finally, it might be the case that the liberal institutions implemented were too fragile because these countries did not have much experience with them, even in pre-communism era. In contrast to Germany, for example, which was already embedded in the West before fascism took over – and where, because of this, there was a tradition more susceptible to the liberal order – Eastern Europe had less experience.

Collins (2019), for example, argues that in the case of Hungary, “it would be more accurate to describe Orbán as the latest in a long line of Hungarian rulers who practiced their own versions of soft authoritarianism.”

Thus,

“A more plausible explanation for recent developments within Hungary is that liberal democracy, having expanded only recently outside its historic core of wealthy states in North America and Western Europe, is now contending with unfamiliar and often inhospitable political terrain.”

The explanation could be a mixture of all of these arguments. It is not to be forgotten, however, that it is not only Eastern Europe which is currently experiencing these backlashes to liberal ideas.

In several countries in the West, such as the United States, Germany, France, Italy, and the Netherlands, movements have made major gains that want a rollback of liberal democratic institutions.

These countries have shown more resilience to these attacks due to liberal democracy having a longer and stronger tradition there than in the East, as well as liberal democracy having been ingrained in the shared mental models of Westerners more clearly, at least since the post-war era (in the United States and the United Kingdom even for many centuries).

Nonetheless, this again begs the question of why so many of our fellow beings are turning away from liberal ideas. Many observers, such as Timothy Carney in his Alienated America (2019), see the main culprit in a loss of belonging, loss of identity and security, weakened civil institutions, and a disintegration of society.

Indeed, “the decline of strong communities with dense social ties” has been ongoing for many decades (VerBruggen 2019). And Carney (2019, 253) finds that especially in Trump Country, predominantly rural areas and working-class people, one will see the erosion of communities and social institutions the strongest:

“if you want to know what happens to individuals left without a community in which to live most fully as human, where men and women are abandoned, left without small communities in which to flourish, we should visit Trump Country.”

Most of the crises of today are particularly prevalent in non-urban areas, a phenomenon which Wilkinson (2019, 4) has called the Density Divide:

“Urbanization, I argue, has sorted and segregated national populations and concentrated economic production in megacities, driving us further apart—culturally, economically, and politically—along the lines of ethnicity, education, and population density.”

This urban-rural divide can be observed around the West, where traditionally liberal parties still win in big cities, whereas illiberal competitors dominate in other places in the country (Olmstead 2018).

Other explanations abound, though we can only focus on a handful more. David Goodhart (2017) goes deeper into the urban-rural divide, arguing that it is not divided into geographical terms only, but also between general attitudes of people, between ‘anywhere’ that follow the creed of Global Citizenry, calling earth home rather than a particular place, and ‘somewhere,’ for whom roots, home, and family are still crucial.

In a different direction go those that see in our world a spiritual crisis, as Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (1978) predicted in his Harvard Commencement Speech four decades ago:

“Everything beyond physical well-being and the accumulation of material goods, all other human requirements, and characteristics of a subtler and higher nature, were left outside the area of attention of state and social systems, as if human life did not have any higher meaning.”

Carney (2019) supports this finding by arguing that in the United States, people living in places with higher Church attendance are much more likely to be happy with the current world (and much less likely to support Trump) than others, regardless of whether they live in an urban or rural area.

Meanwhile, classical liberals will point out that in recent decades, we have seen certain excesses of liberal policies and institutions occur that turned out to be illiberal. The European Union, for instance, under the guise of liberal pretenses, has adopted an increasing number of competencies from national governments.

However, with the European Union governing 500 million people, with them having little say over the decision-making in EU institutions, the EU may have also robbed Europeans of agency and their nature, if we rely on Aristotle (4th century BC, 1253a-1), as political animals.

Finally, when we look at today’s crisis of the liberal order, there might be an inherent weakness of it in that it has changed the way people interact with one another.

While in traditional, pre-liberal societies an order was based on a small, tight-knit group, liberal democracy has brought forth an extended order with millions upon millions of people interacting day in, day out and without knowing each other.

The relationships have thus inadvertently turned from familiar to transactional. Social institutions and concepts of belonging have, thus, been weakened in an internationalist world of supposedly all Global Citizens. The German Ferdinand Tönnies (1887, 8-87) contrasted this on the one hand as Gemeinschaft as in the traditional community, and Gesellschaft as in the larger society.

The paragraphs above can explain the demands for nationalist leaders that attack liberal principles and practices in the name of bringing back identity, belonging, and security.

Just because this change in voter’s preference as well as national policies and institutions of many countries has not resulted in an actual backsliding in the traditional West yet, does not mean that it will never do.

Conclusion

The liberal order is still a relatively young system by and large. Over millennia before the industrial revolution and the ascendancy of liberal ideas did tribalism of some sort or the other prevail. The legacy of liberal order is undeniably impressive. It has brought individuals endless ways to fulfill their lives, to travel where they desire, to trade with whomever they want, and to enjoy civil and political freedoms.

Consequently, the market economy has brought forth immense wealth and enabled hundreds of millions of people to escape poverty. Nonetheless, liberal principles are being attacked today from many corners.

People are not as happy with their effects, with rapid upheavals and disruptions. Has the liberal order failed, or will it fail, as many predict (see, for example, Deneen 2018)?

Not necessarily. If we look, however, at the problems and possible reasons that were described in this paper, we realize that today’s issues and challenges that liberal systems face are not economic in nature.

Thus, the remedy to these crises cannot be economic either. They are political due to ever further centralization, which can have undemocratic consequences in political communities of hundreds of millions of citizens. The remedy is decentralization and a greater focus on local democracy, instead of a further outsourcing of decision-making to supranational organizations.

The problems are social as well as cultural. In this regard, a strong and healthy civil society needs to supplement the liberal order. This part has been missing in recent times.

Finally, the problems are essentially moral. A functioning free society needs to stay close to its moral and ethical foundations that made it possible in the first place – mere markets and endless calls for more freedom are not enough, and, all by themselves, at worst, potentially dangerous to the system’s own continued existence (Levin 2019).

In this, we would do well to follow the example of Friedrich A. von Hayek’s “true individualism” (Hayek 1948). This individualism is based on the view that free individuals are born into a society, into a family, and other institutions (Weiss 2019). Humans are social animals. Traditions, social rules, and institutions – that is, culture – do matter, and humans sometimes prioritize other things in life over mere economic aspects of their lives.

Humans have an innate need for a sense of belonging, for an identity that goes beyond oneself, for strong communities that can help in times of personal crises. Indeed, for the liberal order to remain accepted, it needs to take these considerations into account, or else wither away, replaced by illiberal forces promising to fulfill these needs.

References

Anderson, Ryan T., and Robert P. George. 2019. The Baby and the Bathwater. https://www.nationalaffairs.com/publications/detail/the-baby-and-the-bathwater.

Aristotle. 4th Century BC. The Politics: Book 1.

Bayer, Lili. 2018. “Europe’s eastern tigers roar ahead,” Politico. https://www.politico.eu/article/central-and-eastern-eu-gdp-growth-economies/.

Beck, Martin, and Simone Hüser. 2012. Political Change in the Middle East: An Attempt to Analyze the “Arab Spring”. Hamburg: GIGA German Institute for Global and Area Studies.

Burns, Daniel. 2019. Liberal Practice vs. Liberal Theory. https://www.nationalaffairs.com/publications/detail/liberal-practice-v-liberal-theory

Carney, Timothy. 2019. Alienated America: Why Some Places Thrive While Others Collapse. New York: HarperCollins.

Clark, Gregory. 2007. A Farewell to Alms: A Brief Economic History of the World. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Collins, Will. 2019. The New Authoritarian Hungary That Isn’t. https://palladiummag.com/2019/05/06/the-new-authoritarian-hungary-that-isnt/.

Davies, Stephen. 2018. The Great Realignment: Understanding Politics Today. https://www.cato-unbound.org/2018/12/10/stephen-davies/great-realignment-understanding-politics-today.

2019. What explains the wealth explosion? https://capx.co/what-explains-the-wealth-explosion/.

Day, Matthew. 2019. “Law and Justice party wins one of largest victories in Poland’s democratic history,” Telegraph, 14. October 2019. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2019/10/14/law-justice-party-wins-one-largest-victories-polands-democratic/.

Deneen, Patrick. 2018. Why Liberalism Failed. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Fukuyama, Francis. 1989. The End of History? https://www.embl.de/aboutus/science_society/discussion/discussion_2006/ref1-22june06.pdf.

Goldberg, Jonah. 2018. Suicide of the West: How the Rebirth of Tribalism, Populism, Nationalism, and Identity Politics Is Destroying American Democracy. New York: Random House.

Goodhart, David. 2017. The Road to Somewhere: The Populist Revolt and the Future of Politics. London: C. Hurst & Co.

Hannan, Daniel. 2013. How We Invented Freedom & Why It Matters. London: Head of Zeus.

Hayek, Friedrich. 1948. “Individualism: True and False.” In Individualism and Economic Order, by Friedrich Hayek, 1–32. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Kingsley, Patrick. 2018. “Orban and His Allies Cement Control of Hungary’s News Media,” New York Times, 29. November 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/29/world/europe/hungary-orban-media.html.

Kolev, Stefan. 2018. “James Buchanan and the “New Economics of Order” Research Program.” In James M. Buchanan: A Theorist of Political Economy and Social Philosophy, by Richard Wagner, 85–109. Fairfax: Palgrave Macmillan.

Levin, Yuval. 2019. “The Free-Market Tradition,” National Review, 20. May 2019. https://www.nationalreview.com/magazine/2019/05/20/the-free-market-tradition/.

Marangos, John. 2004. “Was Shock Therapy Consistent with Democracy?” Review of Social Economy 62(2): 221-43.

McCloskey, Deirdre. 2016. Bourgeois Equality: How Ideas, Not Capital or Institutions, Enriched the World. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

2010. Bourgeois Dignity: Why Economics Can’t Explain the Modern World. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Olmstead, Gracy. 2018. “The Urban-Rural Divide More Pronounced Than Ever,” The American Conservative. https://www.theamericanconservative.com/articles/the-urban-rural-divide-more-pronounced-than-ever/.

Open Society Foundations. 2018. The Open Society Foundations to Close International Operations in Budapest. https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/newsroom/open-society-foundations-close-international-operations-budapest.

Our World in Data. 2013. GDP per capita in England and the United Kingdom since 1270. https://ourworldindata.org/uploads/2013/11/GDP-per-capita-in-the-uk-since-1270.png.

Porčnik Tanja. 2018. Nationalism and Populism Detrimental to Freedom. http://4liberty.eu/nationalism-and-populism-detrimental-to-freedom/.

Röpke, Wilhelm. 1960. A Humane Economy: The Social Framework of the Free Market. Chicago: Henry Regnery Company.

Raico, Ralph. 2018. The European Miracle. https://mises.org/library/european-miracle-0.

Redden, Elizabeth. 2018. Central European U Forced Out of Hungary. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2018/12/04/central-european-university-forced-out-hungary-moving-vienna.

Rohac, Dalibor. 2019. “Viktor Orbán and the corruption of conservatism,” CAPX. https://capx.co/viktor-orban-and-the-corruption-of-conservatism/.

Rouanet, Louis. 2017. How Political Competition Made Europe Rich. https://mises.org/wire/how-political-competition-made-europe-rich.

Shleifer, Andrei, and Daniel Treisman. 2014. Normal Countries: The East 25 Years After Communism. https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/shleifer/files/normal_countries_draft_sept_12_annotated.pdf.

Solzhenitsyn, Aleksandr. 1978. A World Split Apart. http://www.orthodoxytoday.org/articles/SolzhenitsynHarvard.php.

Századvég. 2019. “TARTJA ELŐNYÉT A FIDESZ-KDNP A GYURCSÁNY VEZETTE ELLENZÉKKEL SZEMBEN”. https://szazadveg.hu/hu/kutatasok/az-alapitvany-kutatasai/piackutatas-kozvelemeny-kutatas/a-fidesz-kdnp-elonye-toretlen.

Tönnies, Ferdinand. 1887. Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft. Leipzig: Fue’s Verlag.

Tepperman, Jonathan. 2018. “China’s Great Leap Backward,” Foreign Policy, 15. October 2018. https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/10/15/chinas-great-leap-backward-xi-jinping/.

Vásquez, Ian, and Tanja Porčnik. 2019. The Human Freedom Index 2019: A Global Measurement of Personal, Civil, and Economic Freedom. Washington, D.C.: Cato Institute, Fraser Institute, and Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom.

VerBruggen, Robert. 2019. This Is How You Get Trump. https://freebeacon.com/culture/review-alienated-america-timothy-p-carney/.

Vlahos, Kelley B. 2019. “George Orwell’s Dystopian Nightmare in China,” The American Conservative. https://www.theamericanconservative.com/articles/george-orwells-dystopian-nightmare-in-china-1984/.

Weber, Max. 2002 [1904]. The Protestant Work Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. New York: Penguin Books.

Weiss, Kai. 2019. Why We Need Hayek Today. https://www.austriancenter.com/why-we-need-hayek-today/.

Wilkinson, Will. 2019. The Density Divide: Urbanization, Polarization, and Populist Backlash. https://www.niskanencenter.org/wp-content/uploads/old_uploads/2019/06/Wilkinson-Density-Divide-Final.pdf.

Zweynert, Joachim. 2004. Shared Mental Models, Catch-up Development and Economic Policy-Making: The Case of Germany after World War II and Its Significance for Contemporary Russia. Hamburg: Hamburg Institute of International Economics.

Zweynert, Joachim, and Nils Goldschmidt. 2005. The Two Transitions in Central and Eastern Europe and the Relation between Path Dependent and Politically Implemented Institutional Change. Freiburg: Freiburg Discussionpapers on Constitutional Economics.

The paper was published in The Visio Journal No. 4. Cite the paper: Kai Weiss, “The Liberal Order and Its Backlash: Transition and Realignment in Eastern Europe and the West,” The Visio Journal no. 4 (December 2019): 1-11.

The article was originally published at: http://visio-institut.org/the-liberal-order-and-its-backlash/