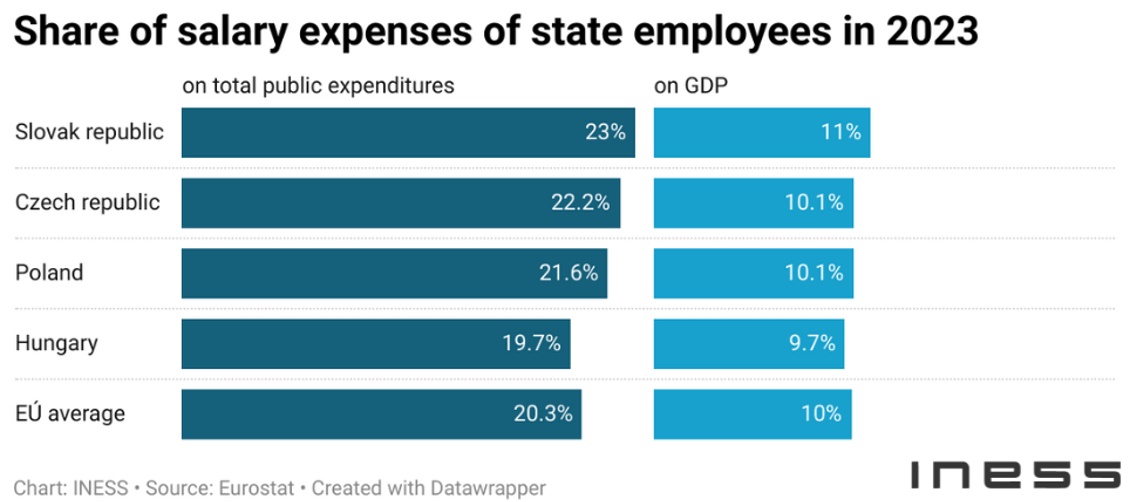

The current process of negotiating salary increases for public servants should also be seen in the context of international comparisons. Slovakia spends the most on salaries in the whole V4, not only as a share of total public administration expenditure but also as a share of GDP. In these comparisons, Slovakia spends more than the EU average.

In 2015, public employees’ salaries accounted for 8.9% of Slovakia’s GDP and absorbed 19.5% of public spending. Last year, it was already 11% of GDP and 23% of public expenditure.

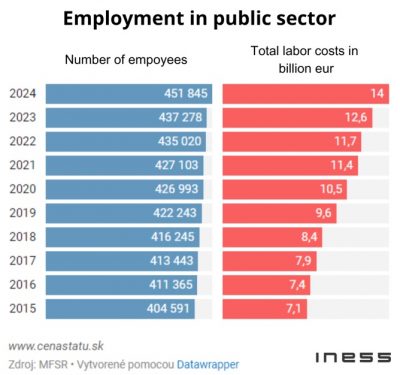

This development and Slovakia’s position in the comparison above is not surprising. The number of public administration employees has been growing steadily over the last 10 years.1 47 000 employees have been added, an increase of 10.5% of the workforce. This has naturally been reflected in the growth of the total wage bill of public employees, which has doubled over the period. The reasons for this development are still the same. Inefficient digitization, the ossification and inefficient management of the public sector, and, above all, the many unnecessary tasks that public sector employees have to carry out.

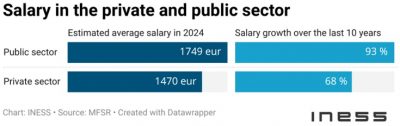

The growth in wage expenditure was also reflected in stronger average wage growth in the public sector than in the private sector. According to the Ministry of Finance’s macro committee estimates, the average wage in the public sector is expected to be EUR 279 (19%) higher than in the private sector this year.

The unions’ demand for salary increases is estimated at €1.5 billion, which would be an 11% year-on-year increase in wage expenditure.2 The increase in wage expenditure is not justified in the context of past salary increases, the fall in inflation growth, international comparisons, and, above all, the record public deficit.

From the perspective of the sustainability of public finances but also of the quality of public services, it is necessary to reduce the number of public employees, in particular by reducing the number of activities carried out by the sector. The savings thus obtained should be used to reduce the state deficit, partly by selectively increasing public administration wages (for example, table wages below the minimum wage).

The government’s proposal to provide a one-off 500-euro contribution would represent an additional cost of 200-250 million euros next year. This is a significantly less costly solution than the trade union demand and could be financed with a 1.4% reduction in the number of state employees. Given the shortage of staff in the labor market and the low unemployment rate, there has never been a better time for public sector redundancies than today.

The worst approach to resolving the current pay dispute would be to increase salaries funded by tax increases. Most of the additional tax burden would have to be paid by the private sector, slowing down economic growth and further increasing the gap between private and public sector salaries. Taxpayers would thus have to contribute more to low-efficiency public services.

1) Due to a change in methodology, the public administration sector has expanded to include several state-owned enterprises that were previously not included in the public sector. However, most of these changes took place before 2015.

2) It is unclear whether this KOZ recalculation includes salary increases for all employees. Doctors receive salary increases according to the salary schedule; the armed forces have their collective bargaining agreements.

The data for the article can be downloaded here.

The article is another in a series of INESS reports highlighting the scope for austerity in public spending to prevent potential tax increases.