The process of European unification was one of the great political achievements of the 20th century. It gave Europeans – and with it, Germans – freedom, peace, and prosperity.

It continues to be the aim of a liberal Europe to ensure freedom in politics, economy, and society, to safeguard peace and boost prosperity, and to give young people in particular a vision of Europe where they can live, learn, study, work and travel as they please, without having to contend with internal borders.

Europe’s unification is a quintessentially liberal project: liberals believe in the creativity and strength of the individual and in giving people the opportunity to make the most of their own potential. This is done by building an institutional framework, based on liberty, that encapsulates the essential aspects of an open and pluralistic society: the rule of law, protection of fundamental human rights, as well as democracy and free markets.

Worldwide, people continue to strive for freedom. But the value system of liberal democracies and free markets is facing increasing pressure to legitimise itself. Liberals can only address this challenge by providing responses to today’s great global issues. In these times, such answers are needed more than ever.

As Europeans we are experiencing the great benefits that liberty brings. Free and peaceful interactions in a flourishing domestic market have brought us unparalleled wealth. In times of rapid globalisation the European Union helps to secure freedom, peace, and prosperity in Europe. But this process of integration is risky and, for some, threatening.

Decisions are being increasingly centralised. Decision-makers are becoming further and further distanced from citizens. And there is a lack of clarity about the political level at which responsibilities should be assigned, based on the principle of subsidiarity.

These developments, and the question of how the various organs of the EU are politically legitimated, place at risk the acceptance of the integration process. The Euro crisis has exacerbated these underlying problems and brought them to the fore, where everybody can see them. It is the responsibility of politicians to adhere to the rules and benchmarks they themselves have set. Otherwise citizens will lose their trust in the process of European unification.

Europe faces considerable challenges. The causes of the Euro crisis have to be combatted effectively to make Europe more capable of action and to avert harm from its citizens. Europe has to organise itself in a way that maximises the opportunities globalisation offers its citizens, and democratic principles have to be strengthened at all levels.

Increasing centralisation and protectionism have to be countered. The principle of competitive federalism needs to be reinforced because it plays a key role in enabling sustainable progress. Building a sensible and binding system of rules that complies with the principles of democracy, the rule of law and a social market economy requires clear assignment of responsibilities, democratic legitimation and supervision of institutions.

The idea of a unified Europe, capable of effective action, has to be revitalised in the face of these challenges. This is a vision for Europe as a federation of sovereign states, where matters which individual states or their federal levels cannot decide on on their own are jointly decided, based on a partial transfer of sovereign rights.

Building this Europe is one of the great tasks of the future.

1: Promote European Diversity: Integration as An Open Process

What makes Europe special is a great diversity in a relatively small area. Its wealth of history, languages, architecture, literature, music, painting and culinary traditions is extraordinary.

This diversity deserves to be preserved. The European identity is a kaleidoscope of historical and cultural linkages. All of these facets are bound together by shared cultural and legal traditions, as well as values which have marked Europe’s history. In particular, they include the medieval separation of worldly and spiritual authority, and of princely and corporate power, which evolved into the basis of the Western understanding of freedom, individualism and pluralism.

This European identity does not compete with the respective national, regional or local identities of citizens. European integration is a valuable asset, but it is no end in itself. We should not interpret it as a linear process. Instead, integration has to remain an open process that is supported and desired by the member states and their citizens. Europe has to grow organically and be carried by the free will of its citizens.

The question of Europe’s future structure should be discussed openly and without preconceptions. Whether the quality of this federation of states will change, and how, depends entirely on us as Europeans; it is an evolutionary process for which there is no historical precedent. Locking the EU into an institutional or geographical finality would rob this process of chances and opportunities. It is important that as Europeans, we express our dedication to our values and goals, follow our own rules, and act based on a sense of shared responsibility.

2: Allow Europe to develop at different speeds

European integration will endure if citizens support it. Even today’s EU, with its 28 members, is much too heterogeneous to integrate at a single pace. We need a process that accommodates different speeds and degrees of integration.

States that wish to participate in the development of the EU at a slower pace, or not at all, should not hold back the others. Where joint action is not possible or required, a “Europe of different speeds” would enable political progress to be made, and would allow more flexibility in timing while taking into account national specifics.

The example of the monetary union illustrates perfectly how important flexible solutions are. When a country is unable to bear the pressure of a hard currency and is clearly out of its depth when it comes to restoring its competitiveness and its debt-carrying capacity within the monetary union, it endangers the entire union’s existence.

That is why in the future, in addition to the possibility of state insolvency within the Euro currency area, Euro member states should be able to withdraw permanently or temporarily from the joint currency, while being given the possibility to return, subject to clearly defined conditions. This method is also Europe-friendlier because it makes the Eurozone – with states that are able to stand on their own two feet economically – more attractive for new members.

3: Ensure That Europe Is Able to Act Effectively

In areas for which the European Union is indisputably responsible, it has to be capable of action when required, and not only when addressing typical core tasks such as the customs union, competition law for the domestic market or common trade policy.

In a globalised world Europe can only defend its interests if it is capable of action in critical areas of policy and able to speak and act with one voice in its external relationships. “More Europe” is required particularly in dealing with issues of migration and asylum, in combating international criminality, and in dealing with cross-border environmental pollution.

The EU also has to work more closely together in defining its approach to securing sources of energy and raw materials, in creating European power infrastructure, and in its energy relationships with non-EU countries. Where there is an European responsibility, it should be exercised. This is true especially of integration in the area of Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP). But taking this to its logical conclusion would have far-reaching consequences: at the end of the process the EU would be sovereign in foreign and security policy and be exclusively responsible for these areas.

In such a case, for the EU to fulfil its duties, all member states would have to contribute.

Europe’s military capacities should be used jointly and more effectively in the context of “pooling and sharing”. Against the background of severe financial constraints it is essential that Europe’s defence capabilities be used more efficiently.

European structural policies also require reworking. The European structural funds should be designed to be degressive in nature and their effectiveness should be continuously monitored. In order to improve the competition conditions of structurally disadvantaged regions, regional and transnational cooperation should rather be promoted.

When European agricultural policy was launched in 1957 the goal was to provide farmers with adequate living conditions, to stabilise markets and to ensure security of supply. But in the face of liberalised global markets, these goals are no longer at the centre of attention. The European domestic market and world markets ensure sufficient supply. It is therefore urgently required that the Common Agricultural Policy be reoriented along free market principles.

In accordance with the principle of subsidiarity, the member states or regions should redefine agricultural policy to ensure that citizens are provided with high-quality food, that our cultural landscapes are maintained and farmers and their families are provided with adequate livelihoods.

Both politically and culturally, Europe is characterised by great heterogeneity. This heterogeneity and the structures resulting from it have to be taken into account in the further development of the EU. Anyone who believes that the details of social policy, wage policy, R&D policy, technology policy or even regulating national or regional economies can be organised jointly underestimates the inertia, but also the productivity of the prevailing differences. Moreover, democratically legitimised integration will only succeed if the principle of subsidiarity is enforced and if responsibilities are assigned unambiguously.

4: Enforce subsidiarity, prevent the gradual encroachment of centralisation

Subsidiarity means simply that problems should be solved by the smallest unit capable of doing so. Problems are only passed on to the next higher level if the lower level cannot solve them. As a rule of thumb: “small before large”, “private before state”, “local before central”.

Subsidiarity creates closeness to citizens. Subsidiarity creates transparency. Subsidiarity creates competition. It is important to delegate as much responsibility as possible to local authorities, regions, and member states. This is the only way of ensuring that the EU remains a flexible and democratic system. That is why the principle of subsidiarity has to be given greater importance in the European order, especially with regard to shared responsibilities.

Currently, higher authorities are often too quick to intervene. Instead, it would be better to check first if citizens or local, communal or regional authorities can deal with the issue. If a decision can be made at the regional or national level, there is no reason to delegate matters to the supranational level, that is the level of the EU. Emphasising the principle of subsidiarity should not be seen as Euro-scepticism. It is a method for ensuring that public tasks are accomplished as efficiently and as closely to citizens as possible.

The tendency towards ever greater centralisation and mission creep has to be counteracted more decisively. The pre-emptive checking of subsidiarity by national parliaments should be strengthened and developed further.

In addition to formal and legal subsidiarity checks, national parliaments should also engage more strongly with the objectives and content of European initiatives and introduce their positions into the European process of opinion forming and decision making at an early stage, if necessary through the national governments.

Furthermore, it is necessary to set up a second senate of the European Court of Justice, which can be appealed to in cases of doubt or dispute and which decides on the basis of the principle of subsidiarity whether the EU may in fact exercise a responsibility.

5: Clearly assign institutional competencies, strengthen democracy

The democratic legitimacy of the European Union rests on the European Parliament, and is derived indirectly from the national parliaments, which control their ministers in the Council. The Lisbon Treaty for the first time anchored the rights and duties of the national parliaments in European primary law and thus helped to reduce the democratic deficit. We therefore welcome the strengthening of the national parliaments’ participation rights.

European Parliament

Votes in the European Parliament are weighted according to the principle of degressive proportionality. This principle ensures that the number of delegates of an EU member state is not directly proportional to the size of its population. Small states are relatively overrepresented as a result of the principle.

This means that the votes of delegates to the European Parliament have unequal weightings and represent different numbers of citizens. The vote with which one citizen elects a delegate may therefore not be equal to the vote of another citizen. This is an infringement on the principle of democracy. This disadvantage has to be eliminated by introducing a uniform voting law that provides base mandates to protect smaller states.

Although the different vote distributions in the Council of the European Union reflect the differing population sizes of the member states, this effect does not compensate the negative impact of degressive proportionality in the European Parliament elections and can only be resolved by changing the electoral law.

We call for a right to initiate legislation for the European Parliament. Today, the European Commission is the only EU institution with the right to propose legislation, even though it only has indirect democratic legitimacy. The European Parliament does have the right to request the European Commission to table a proposed law. If the Commission does not accede to the request, it must justify its decision. But the current arrangement is not suitable for a future European Parliament assembled on the basis of a reformed electoral law and which has direct democratic legitimacy.

European Commission

In terms of the Lisbon Treaty, the European Commission was to be reduced in size to a number corresponding to two-thirds of the number of members of the EU by the autumn of 2012. This reduction in size makes sense and is necessary. Contrary to the resolution passed by the European Council on 11/12 December 2008, the reduction should be implemented in order to make the Commission as a whole more effective and in order to avoid further fragmentation and the increased accumulation of competencies by the individual commissioners. But in view of plans to accept additional members into the EU, even the reduction already decided on will not be sufficient, meaning that further reductions will become necessary.

Directly electing the Commission’s president would give him or her the greatest legitimacy of all European organs, but it would not provide the president with the corresponding authority. Inevitably, the president would have to disappoint expectations. Instead, the current procedure should be maintained.

European Council and Council of the European Union

The European Council is made up of the heads of state and heads of government of the European Union member states. It is chaired by the president of the European Council, who is elected for a two-and-a-half year term of office.

6: Design just and future-proof financing

The funding of the EU is an on-going point of contention between the member states of the European Union. The debate revolves around the so-called own resources and the contributions by the individual member states on the one hand, and the amount and structure of expenditure on the other hand. For as long as raising taxes remains the exclusive right of the sovereign states, this right cannot be transferred to the EU. This is true independent of whether such a tax is raised by the member states and forwarded on to the EU or whether the EU is given the right to raise its own taxes. The EU’s debt ban should be maintained. Similarly, the EU’s level of expenditure should continue to be limited by the upper limit of own resources.

A joint European tax policy would not promote the aims of the EU

Independently of EU budget policies, the harmonisation of tax policy within the EU is a recurrent topic of discussion. But a joint European tax policy would not promote the aims of the EU.

Tax competition between EU member states does not lead to a race to the bottom, as is often claimed. Instead, it contributes to the competitiveness of the individual member states. Only while member states continue to have the possibility of reacting to economic developments quickly and flexibly by adjusting their tax rates can the overall European objectives be achieved.

Because of the heterogeneity of the member states’ economies, a uniform tax rate for direct taxes (income, profit) should be rejected. Tax competition in this area makes sense and is necessary. Different reasoning applies to the Europe-wide specific consumption taxes, which are reflected directly in prices. In this area comprehensive harmonisation makes sense and is urgently required to avoid undesirable developments (petrol tourism, cigarette smuggling) and to prevent competitive distortions.

7: Use market mechanisms to resolve the Euro crisis

The monetary union’s stability architecture should be based on the obligations of the member states to take responsibility for maintaining budget discipline and on the independence of the European Central Bank (ECB). The Euro crisis revealed a key flaw of the European monetary union: there was no effective mechanism to stop member states from taking on too much debt. The EU’s existing supervisory mechanisms were not being consistently applied. Regulatory safety mechanisms, like the stability and growth pact, were not adhered to.

Ways out of the crisis

The monetary union can only exist in the long term if it is a stability union. The economic principles of the stability community – in particular the prohibition of mutual budgetary assistance by the Euro states (no-bail-out rule) – have to be fully restored. Decision-making and liability belong together. What is true in private law has to apply to states, too.

Any mixing of responsibilities based on joint liability – no matter in which form – should be rejected. Every single member state has to fulfil the stability requirements on its own account.

Collectivisation of debt has to be avoided in the Euro crisis. It tempts parties to abrogate their obligations at the expense of others (moral hazard). Eurobonds, a fund for the joint liquidation of debts, or other variants of joint liability violate the principle of national financial sovereignty.

The crisis requires solidarity, provided that this helps to restore the original design of the monetary union as a stability union. Therefore limits have to be placed on the duration and amount of assistance, and it has to be linked to conditions. Individual member states can be provided with temporary assistance using the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) and the European Stability Mechanism (ESM).

The assistance defined in the EFSF and the ESM should not be supplemented or replaced by further ECB measures on a permanent basis. The ECB’s legal obligation to maintain monetary stability must remain its primary goal in future, as well. Its independence and the prohibition of public financing must be respected and maintained.

The fiscal pact served to catch up on necessary steps towards financial policy integration, which are aimed at improving expenditure discipline. Specifically, the introduction of binding debt limits for Euro states and automatic penalty mechanisms against budget offenders should be welcomed. In principle, penalties should be designed to correct misguided budget policy automatically, for instance by means of an increase in the turnover tax.

From the perspective of the real economy, the inefficiency of deregulated financial markets generally leads to market failure. It is not necessarily more, but better regulation of actors and their behaviour that is required to make financial markets function efficiently.

This is why it is right that the EU should be given efficient banking supervision. The ECB’s monetary independence has to be preserved in its entirety and its statutes should not be touched. In particular, monetary and supervisory competencies should not be mixed and should not be given to the same decision-makers.

At the same time it must be ensured that the capital adequacy of banks is raised to increase their risk aversion (e.g. Basel III). To begin with, the states should be obliged to set up their own protection systems for bank deposits, which should be funded by the banks. Banks that have miscalculated should be able to leave the market in an orderly fashion. This urgently requires a European legal framework for the orderly insolvency of financial institutions. If such measures help to make the financial sector as a whole more robust, the risk of contagion is lessened. Orderly bank and state insolvencies become possible and the prohibition on bail-outs can fulfil its purpose and be applied consistently.

The divergent competitiveness and reform capabilities of European member states have their origins not only in different economic departure points, but also have deep cultural roots and do not change overnight on instruction from Brussels. It remains the responsibility of member states to create an environment that enables competition. Only they are able to do this.

By bringing the domestic market to completion, it can help ensure that areas that hitherto have been protected are exposed to some competition. And by concluding liberal trade deals it can reduce barriers to international trade and thus unleash the forces of economic growth.

Outlook

The European Union’s three goals remain unchanged in the 21st century: to ensure that Europe’s citizens can live in freedom, peace and prosperity. This can be achieved neither through renationalisation nor by transferring the concept of the national state to the European level. Instead it requires a continual assessment of the tension between transferring competencies and respecting subsidiarity.

Europe will remain strong and attractive if it stays true to its liberal roots: by respecting democracy and the rule of law at all levels, protecting fundamental and human rights, pursuing a regulatory policy that corresponds to the rules of free markets, and by presenting a united front outwardly while using and protecting its diversity internally.

The article is based on recommendations by a panel of experts chaired by Dr Hermann Otto Solms, a Member of the Bundestag, formulated in Resolution of the Board of Trustees of the Friedrich-Naumann-Stiftung für die Freiheit, 22 March 2013.

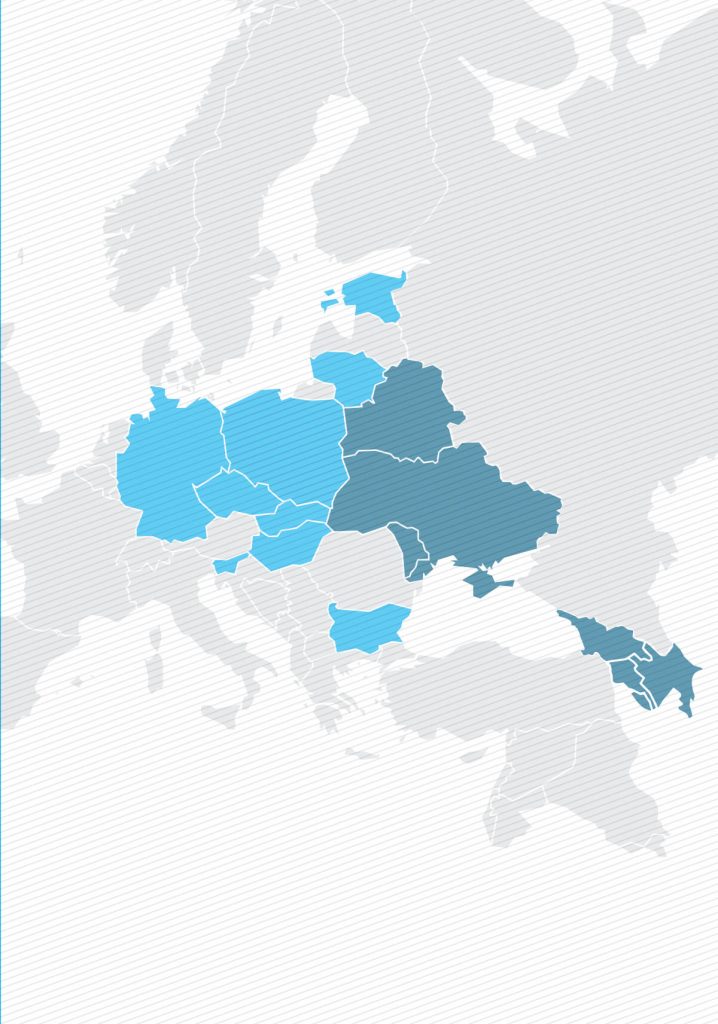

The article was originally published in the first issue of “4liberty.eu Review” entitled “The Eastern Partnership: the Past, the Present and the Future”. The magazine was published by Fundacja Industrial in cooperation with Friedrich Naumann Stiftung and with the support by Visegrad Fund.