Since November 2013 the world has turned its gaze towards Ukraine. The country, which in its attempt to gravitate towards the West has been trying to break away from the Russian impact, is now on the brink of a civil war. What Ukraine can do to solve its problem is not the only important matter; the role of the European Union as well as Ukraine’s neighbours, the Visegrád countries, has also become a crucial factor in resolving the crisis.

Ukraine’s position between the East and the West

Similarly to other countries in Eastern Europe, Ukraine was a part of the Soviet Union until declaring its independence in 1991. Ukrainian politics following the turn of the century can be seen as a fight between the East and the West: in the 2004 elections Viktor Yanukovych, a politician of Russian favour and Viktor Yushchenko, supporter of politics more open to the West, ran for the presidential seat. The unstable pillars of democracy in Ukraine became apparent when Yuschenko’s victory came only after a series of election-scandals and mass protests – the so called Orange Revolution – and who, as a result of a lack of political support, was unable to fulfil his political objectives. In 2007 the possibility of a more westernized style of politics emerged again with the appearance of Yulia Tymoshenko, who, however, was sentenced to jail after she and Vladimir Putin signed a contract putting an end to the Russian-Ukrainian gas-conflict. Following the elections in 2010, the opportunity of power-construction was given to Viktor Yanukovych, who, although being a believer of Russia-friendly politics, mainly sought his own interests.

In November 2013, Yanukovych withdrew from the association agreement with the EU, thus openly turning his back at the Union as well as all the western aspirations. As a response, the Euromaidan, an oppositional movement, organized protests on the central square of Kiev, which due to their persistency, eventually evolved into bloody conflicts with the authorities in the February of 2014. Meanwhile, similar movements began to emerge in other cities of Western Ukraine as well.

The ongoing violence evoked international reactions: the French, German and Polish ministers of foreign affairs travelled to Kiev, where they signed an agreement with Yanukovych about resituating the constitution of 2004, which limits presidential power; thus, the ongoing bloodshed was temporarily stopped. On the same night, Yanukovych left his presidential estate and with his bodyguards, moved to an unknown location.

At the end of February, Russia started its invasion of the Crimean Peninsula. Later they announced the annexation of the Crimea to Russia. However, the situation is becoming more aggravated every day and military tensions between the two countries are also increasing. One of the shocking results of the conflict was the shooting of a Malaysian airplane by Russian-supported rebels near the borders of Donetsk on 17 July. All passengers, that is 295 people, lost their lives. This was the first sign indicating that the Russian-Ukrainian conflict posed an international threat.

Although according to its constitution, Ukraine respects human rights, the rights to freedom, it operates a plural-party system and organizes democratic elections, the events of the Maidan Square prove that its system can hardly be considered as a democracy. It seems as though Ukraine wished to step onto the path of democratization and approach the West. However, the country is trapped in deeply rooted problems such as its oligarchic system, the all-pervading corruption, social conflicts and the oppression of civil initiations.

After declaring its independence in 1991, fast and unmonitored privatization gave birth of oligarchs and clans whose descendants, even today, practice a strong political influence in the country. The examples of both Viktor Yushchenko and Yulia Tymoshenko prove that without the support of oligarchs, presidential aspirations are destined to fail.

Civil union against these problems is largely hindered by the fragmentation of the society: while one group wishes for freedom and democracy and envisions entering the EU at some point in the distant future, another part of the same society, especially the Russian natives of Eastern Ukraine, welcome the interventions of Putin.

Hungary – the old-new ferry

Similarly to Ukraine, the dilemma of “East or West” seems to have been recently renewed in Hungary. For a long time it seemed as if with the end of communism in 1989, Hungary had committed itself to the West. However, due to the politics of the Orbán-government, the country is again a ferry beating between the East and the West: it is getting closer and closer to Russia and to the East in general, while western values and relations become deemphasized.

After more than forty years of Soviet rule, the governmental change, the collapse of communism became known in our history as a glorious and “peaceful revolution” – people welcomed democracy and newly won rights to freedom with great enthusiasm. Later, on the 2003 referendum, more than 80% of voters opted for joining the European Union. However, in so little as a decade after the referendum, the country went through a change of political image: the Orbán-government openly and strenuously communicate the change of the political direction, the so-called “eastern opening”. The prime minister often emphasizes the vision of the declining West, suggesting that we turn our attention to the slowly growing countries of the East, because they might cause surprises. Recently, Hungary has made many spectacular and shocking allowances for the East (for example a memorable gesture was the extradition of Ramil Shafarov to Azerbaijan – a man convicted of the brutal murder of an Armenian soldier and sentenced to life imprisonment in Hungary). In Azerbaijan, Safarov was immediately released with a presidential pardon. His extradition tightened connections between Hungary and Azerbaijan, but completely destroyed our partnership with Armenia.

Hungary seeks to tighten Russian relations as well – a huge step towards this aim was when in January Viktor Orbán and Vladimir Putin signed a contract on the use of nuclear energy for peaceful purposes, which included the building of two new nuclear power station blocs in Paks with the strong support of Russia. The agreement lead to a huge uproar, since it was not preceded by any form of political or social debate. The signing was rushed and kept in secret. Furthermore, the matter of our energy-dependence on the Russians occurred just when Russia invaded the Crimea, expressively declaring its power and influence.

Despite the growing concern of the opposition and various trade associations, the politics of the eastern opening continues. In his speech recently given in Tusnádfürdő, Viktor Orbán stated that Hungary can only become competitive if it breaks away from dogmas and ideologies prevailing in Western Europe and choses a new type of social construction instead – that is, if it gives up liberal democracy and tries to understand and follow the success of countries that are not liberal or not even necessarily democratic, such as Singapore, China, India, Russia or Turkey. Many view Mr. Orbán’s statement about turning towards illiberal democracies as a downright and open declaration of dictatorship and, indeed, it did evoke negative reflections across the international media. According to several studies, Hugary’s new political style can be defined as a form of “putinism”, because it is built on the elements of nationalism, religion, conservatism, control over every aspect of the social and economic sectors and the regulation of the media – all typical of the Putin-governed Russia.

Mr. Orbán’s decisions to be more open to the East are complemented with strong anti-EU politics. Ever since the formation of the Fidesz-government in 2010, the Prime Minister’s frequently used phrase, “we’re not going to be colonized”, has become an adage; this refers to the notion that Hungary will not let anyone from abroad to dictate the rules based on foreign interests. Furthermore, it “defends the interests of the Hungarian people” and it is strong enough to win the “fights with Brussels”. Fidesz’s campaign slogan for this year’s European Parliamentary elections also embraced this idea – “Tell Brussels: respect for the Hungarians!”

After winning the elections in 2010, Fidesz made numerous decisions that meant distancing Hungary from the democratic values of the West. Its two-thirds majority in the Parliament enabled the party to make and accept laws of crucial importance without debating the opposition or to write a contradictive constitution that has been amended several times since it first came into effect – it could also centralize the operation of state authorities, limit the power of the Constitutional Court, or offend the critical media’s freedom of speech. It does not initiate extended social consultation, nor does it consider NGOs as partners; recently it even mounted an open offensive against them. The Government Control Office is now examining the projects of the Norwegian NGO Fund on the accusation that its organizations are lobbying in Hungary following foreign and opposition interests. In his speech in Tusnádfürdő, Mr.Orbán told his audience that Hungarian NGOs are not volunteer organizations constructed from the bottom-up but paid political activists, who try to realize foreign interest in Hungary. The Fidesz-government’s activities destroying 25 years of accomplishment is a cause for concern: after just having been able to acquire the liberal system of values following a slow period of construction, they now turn their backs and start building a government, the efficacy of which is highly questionable at best, let alone the elements of strong centralization and nationalistic attitudes, where opposing criticism is being silenced and decisions are not based on comprehensive social and professional consultations. Mr.Orbán is persistent in trying to secede Hungary from the European Union’s influence, while at the same time he yields to another, namely, our energy dependence on Russia. Through this pact, Hungary might get under the influence of an empire that is now proving in Ukraine that once a nation is in its hands, it is willing to do anything in order to keep it.

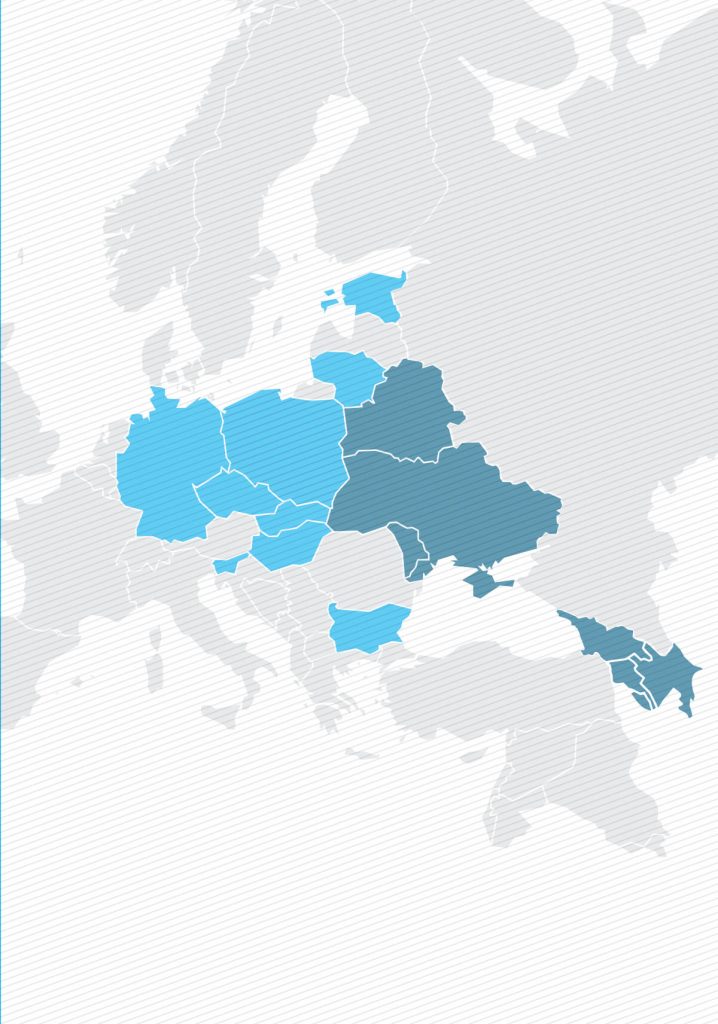

Reactions of the Visegrád countries to the Ukrainian crisis

The situation in Ukraine falls under different evaluations by the four countries of the Visegrád Group. The harshest criticism and opposition against Russia came from Poland; Slovakia and the Czech Republic would stand by Ukraine, but they share concern over their economic relations with Russia, whilst Hungary’s statements can be seen as forgiving, if not almost completely indifferent. From the point of view of the Visegrád Cooperation it would be extremely important for the countries to give a coherent response to the Ukrainian crisis and to precisely articulate the necessary actions to be taken. However, reaching a consensus seems to be so far, that several analysts warn for the collapse of the V4.

Poland’s reaction to the conflict is largely determined by its history of close relations with Ukraine. The Polish have always held the eastern partnership in high regard as well as bringing not only their closest neighbours, such as Ukraine and Belarus, but also Moldova, Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia, closer to the West. After Poland joined the EU, these ambitions grew even stronger; the centre of the country’s eastern politics is still Ukraine. The Polish government took on an active role in resolving the Ukrainian-Russian conflict, when in February, together with France and Germany, they managed to stop the ongoing bloodshed in the country and contributed to the overthrowing and eventual escape of Viktor Yanukovych.

In accordance with this, in its statements about the Ukrainian crisis, Poland harshly condemns Russia and urges international action, criticising the Union for its hesitation. In an interview, Włodzimierz Cimoszewicz, the chair of the Polish Foreign Affairs Committee, said that people have to prepare for a possible cut-off of all Polish-Russian relations. Considering Hungary’s growing dependency on the Russians, for us to issue such statements is unimaginable. After the tragedy of the Malaysian airplane, Poland immediately articulated its firm stance on the event: they considered the attack and the “rejection of the obvious” unacceptable; whilst, they supported the resulting EU sanctions, calling them necessary even if there was a price to pay.

The standpoint of the Czech Republic and Slovakia regarding the situation is less determined, although by no means indifferent. The Czech government assured Ukraine of its support and recognized that Russia offended the territorial sovereignty of the country. However, unlike Poland, neither the Czechs nor the Slovakians urged EU sanctions against Russia out of concern that the situation of their countries’ economy could become endangered. Both the Czech Republic and Slovakia mainly have its gas imported from Russia, hence the emphasis on why their economic relations with Russia cannot be cut off.

From among the V4 countries, or, in fact, it appears that from among all the member states of the EU, Hungary was the one issuing the most forgiving statements about Russia. Fidesz’s reaction to the Ukrainian situation was somewhat delayed and primarily focused on the Ukrainian side: the party emphasized that the construction of a democratic Ukraine was in Hungary’s best interest and that it was important that the country was not susceptible to provocation and that it should try to peacefully resolve its crisis. Although they did recognize that Russia offended Ukraine’s territorial sovereignty, they did not expressively condemn and reject these actions. One reason for this could be that the Ukrainian-Russian conflict broke out right before the Hungarian parliamentary elections and the governing party tried to avoid its Russian relations’ – thus the controversial contract about Paks signed a month and a half earlier – getting in the centre of attention. The opposition parties, however, used the events to criticize Fidesz for its Russia-friendly politics.

The government was cautious with its reactions about the crashing of the Malaysian airplane and the resulting EU sanctions, as well – Tibor Navracsics, the Minister of Foreign Affairs and Trade said there was no direct evidence that proved Russia’s responsibility in the plane crash and that the EU sanctions were no more than desperate attempts possibly without any effect.

Answering questions after his speech in Tusnádfürdő, Viktor Orbán said “we’re sympathetic with the Ukrainians and we express our condolences with regard to the events happening in the country, but still, we have to focus on our own issues.” This was the first time Viktor Orbán openly expressed his wishes to continue the partnership with Russia in order to maintain energy-security and an uncompromised Russian-Hungarian bond. His statements received harsh criticism from Poland – according to the Prime Minister Donald Tusk, “Hungary is unpredictable, you cannot count on Hungary. Hungary’s leader is completely irresponsible.”

The GLOBSEC (Global Security) Forum this May was the first time all the four leaders of the V4 countries were present. The event was regarded as highly important in the light of the Ukrainian crisis. However, the conference made it clear that the leaders’ opinions differed in many questions. A debate evolved around how serious and urgent the Ukrainian situation really is – there was no consensus on what the adequate response would be on the part of the V4 members. It would, by all means, be necessary to express a shared standpoint about the crisis, as well as regarding supporting Ukraine in terms of its sovereignty and reforms. The extent to which each member state viewed itself as subject to a Russian threat also varied. Therefore, debates erupted about the necessary defence strategies and their financing. The issue of energy-security also became urgent – Eastern European countries mostly import gas from Russia through Ukraine. The question is whether their dependence can be relieved to any extent, whether they can build new relationships that could provide a replacement for Russian gas. This would not only be the interest of all the V4 countries, but of every EU member as well.

Recently, the possible collapse of the Visegrád Cooperation due to inner conflicts has also become an issue. It is true that the V4 do not form a political unity. Nevertheless, their partnership is deeply rooted, quite manifold and therefore stable. A permanent cooperation is necessary with regard to the future, as well as bringing differing opinions closer, so that the members of the Visegrád Group can form an effective alliance to Ukraine.

What can Ukraine learn from the members of the V4?

Although Ukraine’s situation is complex and unique, on many levels it does resemble the processes the V4 countries have already once went through. All four members gained a first-hand experience of the Soviet influence and dictatorship and each of them had to break out of the system on their own, finding new solutions and starting their journey on the rough path towards democracy. One of the reasons why the Visegrád Cooperation came to life at the time was to help each other give up the shared history of Soviet rule and at the same time get closer to and eventually join the EU. After realizing this goal, the V4 countries shifted their focus on other issues, such as nourishing eastern partnerships and the democratization of other once Soviet-ruled countries.

During the communist era, politicians constituted a separate, elite fragment. They enjoyed privileges the ordinary citizen could never have dreamed of, such as owning proper real estates, cars or going on holidays. Thus did decision-makers drift away from everyday life and started making decisions regarding the fate of people, whose life circumstances were completely unknown to them. The political elite of today’s Ukraine is also separate, living in luxurious conditions. Viktor Yanukovych’s residence is a ridiculous and, at the same time, tragic example of the above mentioned: mahogany doors and marble floors, a collection of luxury cars, the golden toilet brush – these were all part of a redundant power-display and sumptuousness.

The V4 countries all experienced what the fear of the Soviet military presence and political imprisonment meant. Citizens were unable to freely speak their minds and protests were retaliated. The events of the protests, the bloody conflicts, the resulting executions and imprisonments of 1956 are deeply rooted in Hungary’s memory, while the Czech Republic and Slovakia both know that military invasion is not necessarily a result of demonstrations and protests; as little as peaceful reforms can also be enough. In 1968 Soviet tanks invaded Czechoslovakia because it attempted to build up a sort of “human-like socialism”.

The bloody clashes on the central square of Kiev are shocking, precisely because they are happening in a country where, theoretically, liberty rights, including the freedom of opinion and speech, were ensured. By attacking the protesters, the Ukrainian system showed its true face – one from which democracy is light-years away. Today crews of Russian invaders are stationed in the eastern part of the country and, as of now, the end of the conflict is nowhere in sight.

A reason for hope, however, could be the fact that in each of the V4 countries the softening and the collapse of the communist system came after people raised their voices. Ukraine has already taken a major step: it expressed its wish for a change. And even if that change will only come after many years of struggle, the events of the Maidan square will certainly be considered as its starting point.

Although Ukraine has a market economy, it faces many problems the V4 countries have already dealt with when they strived to change their socialist planned economy to a capitalistic one. Following the governmental change fast and radical economic changes became necessary, but these did not always succeed. The GDP fell in all of the countries that went through the governmental change and the amount of time it took to climb out of the hole was different for each. Later, however, the economy started to develop and with it, the standard of living started growing.

A lesson about this shift in the economic systems is that if privatization – a fast way of liberalization and economic growth – is done improperly, it can cause severe damages. In Hungary, as well as all the other V4 countries, privatization was rushed and done without any proper legal regulations, which thus was used by company leaders to establish their economic power and to save their illegally accumulated assets. Privatization without a strategy creates vague circumstances in which those who are watchful enough can climb higher and become rich. However, it leaves many disappointed losers behind.

Privatization is hindered by a lack of capital and the lack of professionals as well as debts and the general economic instability. Thus bringing in foreign stock and technology might become necessary, which, however, presupposes political stability. In order to lure in foreign investors, the V4 countries used, among others, methods such as tax relief or even tax exemption, but the low cost of production, raw materials and wages are also attractive factors.

Changing to a plural party system and economic liberalization goes together with the recognition of civil rights and the creation of a civil society. The urge of the communist dictatorship is apparent in the elimination of the opposition, primarily, then all other social communities and clubs, so that it can stabilize its power. When these communities reappeared after the softening of the socialist system, they made major contributions to the end of communism and the evolution of democracy.

What Ukraine can primarily learn from the V4 countries is that democracy and liberalism do not come for free. The road towards changes is long and rough; it can infer economic fall-backs or even human loss. The example of Hungary shows that when ruined, the post-communist shift can break down the enthusiasm for democracy to such an extent that we give up halfway and take a complete turn backwards. It would be useful to think about how such a change of direction, the “orbanization” could be avoided.

Standing by democratic values

The abovementioned examples prove that the well-fought-for governmental change, the warmly welcomed market economy and human rights may lead to disadvantages as well. Similarly to other Eastern European nations, the Hungarian society suddenly found itself facing problems that were not present during the socialist era: unemployment, the growing difference in earnings, the significant economic fall-back were all new phenomena. Zsuzsa Ferge’s public opinion polls showed shocking results: half of the respondents considered the new system worse than the old one and the majority claimed that the best era for their families was the “soft dictatorship” of the 80s. To this day, research shows that quite a few Hungarians think that changing the paternalistic state to a liberal one was not worth it. Since the governments of the last two decades were unable to reach a spectacular close-up to the West, it is no surprise that Viktor Orbán enjoys such widespread support when he explains that liberal democracy is no longer a means to development and that we have to choose illiberal methods instead.

To avoid and eliminate similar situations, Hungary as well as other countries that walk in the same shoes, such as Ukraine, need a series of actions that strengthen the democratic values of the society.

It would be highly important to explain what democracy really means. Reports and research with questions addressing the “man in the street” make us realize from time to time that everyday people are not aware of how important a democratic election is, how it is conducted or how the parliament works. The negligently rushed class of civics in our educational system barely teaches students on how to be more self-conscious citizens. Meanwhile, there are plenty of western examples where teaching democratic values takes up a significant part of school activities. Furthermore, numerous NGOs created programs specifically for high school students with the purpose of teaching them about democracy.

It is necessary to raise the awareness in our citizens that during elections they should use their civic rights and cast their votes. In the speeches of political parties the importance of the elections is always emphasized in the following way: go vote and vote for us! Thus often, the voter does not feel that the importance of voting is not only the interest of the individual parties but also his/her own.

It would also be crucial to let citizens know how they can affect the ongoing issues of their country apart from the elections. Civil initiatives should be encouraged and strengthened by the continuous communication of their importance and by helping their work with various scholarships, grants and financial support.

It is extremely important to strengthen democratic institutional guarantees such as the freedom of the press or the independence of jurisdiction. These are the sacred and inviolable foundation-stones of democracy, the ultimate respect of which must be taught to every citizen.

The respect and love for democracy comes easier, of course, if the country’s economy is boosting. It seems to be true that those who go home with an empty stomach will scarcely feel the urge to stand by liberal values. Hence, it is necessary to make economic reforms that will lead to perceptible development and a higher standard of living. To achieve this, comprehensive social and professional consultation is necessary as well as well-detailed effect assessment. In addition, the governing party and its opposition should find a direction to be followed even by new governments.

Another key task would be to alleviate the “side-effects” of the shift towards market economy: decreasing unemployment and helping marginalized groups as well as integrating them with targeted projects. These problems need solving almost as soon as they rear their head, because by time, groups sinking deeper and deeper on the social scale will accept any system that promises a solution to their problems.

Lessons for the Visegrád countries

The fights in Ukraine remind us that what seems to be obvious – as if it has always been the case – such as democracy, human rights, living without fear, is in fact the result of a huge amount of work and struggle.

Being the closest western neighbours of Ukraine who know and have actually experienced what Ukraine is going through, the V4 countries have to be sympathetic and they need to do something in order to help their partner. Not only because their initial objective when starting the cooperation was to help their eastern neighbours find the road towards democratization, but also because it is in their own interest – the V4 countries themselves are half under the influence of the Union and half under the impact of Russia, thus they are especially sensitive to the Russian-Ukrainian conflict. The V4 can only maintain a good relationship with Ukraine if the country is a democratic, independent and reliable partner.

The fact is, however, that the West has made a mistake when it expected Ukraine to easily yield to its interests forgetting the strong ties between Ukraine and Russia. The cold war ended, now Eastern and Central Europe is democratic. However, Russian interests and business ties still exist and Russia still makes its influence felt in the region. Although we tend to see the situation of the countries in East-Central Europe as one in which they are forced to choose between the East and the West, in reality, these countries do not have much of a choice. They will never have the possibility to exclusively choose one over the other. With its Ukrainian conflict, Russia has proven that it will not let post-Soviet countries slip out of its control. The most Ukraine can do and where the assistance of the V4 can come useful is to maintain a good relationship with both sides and to be cautious in getting closer to the Union.

This dichotomy for Ukraine is also an identity crisis – does it define itself as an ex-Soviet country or does it consider Europe as a norm? Will its society be torn if Eastern-Ukraine pulls towards the East and Western-Ukraine towards the West? Can it achieve progress if it has not yet decided which direction to take? And will it be able to stand by its European goals if now those are light years away and it is fairly easy to become exhausted by the changes and struggles, as the example of Hungary so well demonstrates? Can it ever be real for Ukraine to et closer to the West or will it remain only a dream?

It is the responsibility of the European Union and the Visegrád countries to make the dream come true and to help Ukraine go down this road with as little a loss as possible. The V4 countries are the bridge between the eastern partners and the Union, but for them to successfully fill their role they first need to have a common stance. Currently, the four countries represent three different opinions about the crisis. It would be of key importance to harmonize their statements and decisions as well as define the most crucial steps and act on them.

It is important because it is the Visegrád countries who stand closest to Ukraine – barely more than two decades ago they were under Soviet rule and they struggled through their own liberation. If they do not know what to do against Russia, how can the rest of Europe?

The article was originally published in the first issue of “4liberty.eu Review” entitled “The Eastern Partnership: the Past, the Present and the Future”. The magazine was published by Fundacja Industrial in cooperation with Friedrich Naumann Stiftung and with the support by Visegrad Fund.