Moldova’s national background and the unwanted inheritance

When talking about present day Moldova we have to bear in mind a series of important events which have conducted to the nowadays situation. The issue of terminology is also extremely important. These things matter when analyzing Moldovan leaders’ behavior in several situations they had to face recently.

The Republic of Moldova, which is the constitutional denomination of the state, is a recent name given to the territory between Prut and Dniester rivers. It dates back to 1991, when the Great National Assembly has proclaimed the Independence of the new political entity. The new-born state is smaller than Bessarabia (a name given to it after the Ottoman Empire traded the territory to the Russian tsar Aleksandr the 1st in 1812) and even than the Soviet Socialist Republic of Moldova (SSRM, a name given after its occupation by the Soviet Union on the 28th of June 1940).

This state of facts has lead to a series of consequences, which have much to do with Moldovans’ self-consciousness. This includes a weak devotion to the state, a low level of trust in the state institutions, a weak civic involvement, weak ties between citizens, uncertainty towards future and so on. But the most important feature of the Moldovan society remains the great deal of Soviet inheritance that still shapes the development of the society. Given the fact that the most notable rival of democratization is this Soviet legacy, the inevitable battle between these two in the following years will take place.

Even though terms like communism or democracy were in large use, few people knew what was the real meaning and how did these function. That is the reason why immediately after becoming officially independent, Moldovan citizens, who were educated in the homo-sovieticus way, have elected a new Parliament formed mainly from intellectuals and persons from the once repressed social categories.

These events were part of a large context and the SSRM was one of the last Soviet republics to have shaken the Soviet yoke, which was a major event. Back then very few were concerned about political ideologies or systems, as people weren’t even aware how to live in a pluralistic society, where the ruling party didn’t owe the truth. Only then has regrouping started. Until then people were divided into two main categories: the pro-East and the pro-West. A fact worth-mentioning is that the intellectuals were pro-West, aspiring to implement the Western (European and American) values in their country. Of course, this feature of the national Parliaments from the ex-Soviet republics was found almost in each case.

The first Government of Moldova is known as the first democratic Government and its prime-minister Mircea Druc is still considered to be the first democratic head of Government. The term democratic meant non-Soviet/non-communist, hence freely elected by all the citizens having the right to vote. The term was not denominating a social and political order or ideology in the widely-accepted way. It was an unimportant issue to discuss whether a party is liberal, socialist or conservative. The criteria on the basis of which people voted were slightly different. One of the reasons for that was the lack of political culture amongst citizens. And it isn’t hard to explain why, as before 1989, the Party was deciding everything.

The battle for national power

The quest of the nowadays leaders of Moldova has started back in 2009, when taking advantage of the huge anti-communist protests, they have gained political power and legitimacy. Since then the alliance’s name and format have changed. Between 2009 and 2010 we were talking about the Alliance for European Integration, formed out of 4 parties (The Liberal Democrat Party, The Liberal Party, The Democrat Party and the “Our Moldova” Alliance). After the last one did not make it in the Parliament of 2010, it has merged into the Liberal Democrat Party and a new alliance was formed out of the remaining 3 parties. The name of the alliance was kept. At the beginning of 2013, after a horrendous scandal involving leading public figures and chiefs of institutions, the alliance broke. The Liberal Party became a “half-opposition” party. Since then, the party is not participating in the governing act, but is voting in favor of the main pro-European initiatives.

In May 2013 the present days Pro-European Coalition has been established, formed out of LDP, DP and the new-born Liberal Reformist Party (which has split from the Liberal Party). The event marked a new beginning for the 3 parties, as their presidents have made the step back, leaving in the spotlight their younger backers. This is when the liberal-democrat Iurie Leancă was named the new prime-minister and the democrat Igor Corman has become the head of Parliament. Until now, even when the electoral campaign is ready to start, all the leaders of the Coalition refrain from launching public attacks towards their allies. Besides, LP has lately become very vocal against not so public acts of corruption against the leading parties. This issue is an essential one and there is a consensus in the society, but also among pro-European experts, that having a governing coalition which is refraining from dragging its members down by itself, is better than letting the anti-European forces win the elections. However, this doesn’t mean that the “silent” acts of corruption would be welcomed by anyone.

Although the name and the structure of the ruling coalition changed during the last five years, the European integration has remained its main purpose. This is why some important leaders of the Diaspora, for example, are urging the four pro-European parties to re-unite in an electoral bloc and to have a common electoral list. This gesture is regarded as a guarantee that the unity of the pro-European bloc remains safe, so that even those who became disappointed could be mobilized for the sake of the European integration. This idea has its merits, even though there is an other side of that. Namely, some analysts consider that each of the 4 parties have specific categories of voters. Consequently, it would be smarter to gather all the heterogeneous votes and to ally only afterwards. For example, the Liberal Democrat Party has recently (on September 7th, 2014) organized a huge public meeting named “LDP in favor of Europe”. The event was using only the official color of the party, while the speakers were mainly cheering for LDP’s merits. Ironically, this happened right after the liberal-democrat prime-minister said in an interview that the faith of an eventual pro-European coalition after the elections depends greatly on the way each party chooses to campaign.

A similar line is followed by the liberal leader. He said that there is no way that LP’s voters would trust the other parties, so that every party should go on their own. Regarding the eventual post-electoral alliances, the liberal president said that if the pro-European parties gather all together more than 51%, he will consider it a sign that the citizens are in favor of an alliance. And the citizens’ will is everything for his party. For now, the one thing differentiating the Liberal Party from the other three parties in power is the firm pro-NATO approach, which seems to be one of the key-ideas in their campaign. It is an issue comprised in the party’s program and it has popped out just recently after the events in Ukraine.

However, the main stake consists in not losing the votes of those who were disappointed after voting in 2010 for a Pro-European Coalition. And the number is not small at all, according to recent polls it is situated around 30%. The public political discourse now oscillates between two main ideas, at least among the non-communist voters. The talks are whether the ruling parties deserve another chance, or they have to be punished for a reckless way of governing and for simulating a great deal of important reforms. The first option is far from being a satisfactory one, as the necessity of sending the governing alliance a signal of discontent is huge. Yet, the second one is even worse, as most of the independent actors tend to agree, because the memory of the governing years of Party of Communists (2001-2009) is still fresh, by its abuses and economical degradation.

EU, the new national endeavor

The republic has recently celebrated 23 years of Independence in an atmosphere which is bringing, from year to year since 2009, more and more enthusiasm and “Europeanity”. We could say that this enthusiasm is directly proportional to the achievements of the Government and inversely proportional to people’s disappointment. Starting from that judgment, we might assume that the Government’s achievements are having a bigger impact compared to the usual disappointment of the citizens. The squares and parks were full and the internet was bursting with cheerful wishes and smiles. This is happening because the European idea is a quite engaging one for many Moldovans, and it’s being put on the public agenda as the new national endeavor. This could be a good sign for the three pro-European parties in power, who since not too long have started to filter each and every of their actions through the general purpose of winning in the elections.

From the early beginning of their coming to power in 2009, the Alliance for European Integration has tried to do its best in order to assimilate the European project, so that a true transfer of image could happen. Ideally, the transfer should have occurred from the EU to the Alliance. However, it happened the other way round. This is how many analysts have explained the decreasing of EU’s popularity, the Union starting to be associated with the poor performance of the pro-European parties. Inevitably, in a state striving to bypass the transition and the Soviet inheritance, the parties in power are rarely managing to keep people’s approval for more than two mandates. The temptations while being in power are too strong, while in some cases the experience of the new-comers is too limited. People see this and understand it very well. The good news is that the political leaders have understood it also and have recently changed their ways of acting publicly, promoting solidarity rather that conflicts, “for the sake of the integration”.

Recent evolutions in the European path

Moldova was included in the European Neighborhood Policy in 2007, alongside other former soviet states and some northern African ones. The policy was addressed to the governments, as well as to the civil society, which is considered to be an important player in the process of deepening democracy and making it sustainable in these neighboring countries. Among several financial and institutional instruments that had the role of strengthening the European orientation of the partners, the most important component is the Association Agenda, the “carrot” of the ENP.

The present age of Moldova-EU relations has started in the summer of 2009, when the already mentioned pro-European parties came to power. The key-document of the Government was launched on the 16th of December 2010, right after it came to power. The Action Plan on Visa Liberalization has become since its beginning a source of hope and despair of all the Moldovans. It has generated a continuous debate between all the social layers, the pro-Europeans and the pro-Eurasians, the Power and the Opposition and not only. It has even generated the unaccepted “resignation” of the prime-minister, who was promising periodically that the visa regime will soon be annulled, but the deadlines were broken every time. Some have blamed miscalculations, while others blamed the ”machiavellic” calculations of the ruling coalition, who was simply using any instrument in order to meet people’s great expectations.

The liberalization has finally come on the 29th of May this year, after European Parliament’ announcement, made on the 27th of February. Actually, this proper announcement was the button that was needed to be pushed so that the general enthusiasm started to spread. The enthusiasm was so strong, that it has exceeded the Moldovan borders. Media analysts have reported that a wave of Transnistrian and even Ukrainian citizens started to apply for Moldovan citizenship. A huge information and media campaign was immediately launched, being initially promoted by the Liberal Democrat Party. Later, the other two governing parties joined. Until then they did not manage to fully master the European idea and the merits connected to it. It was a moment when one could notice, more easily than ever, that the parties inside the coalition had at some extent their own agendas and their own messages for their own electorate.

Right after the visa liberalization wave of enthusiasm had passed, the Democratic Party announced that it was time for them to concentrate more on the social dimension, which was for too long neglected due to their partnership with the center-right parties. In the same period of time, the Communist Party has announced that European integration is actually not so bad, and that Moldova should make the most out of this. Soon some leavings followed and the communists’ opposition became even more faded than before. This chain of events prompted many experts to talk about a possible center-left alliance between the democrats and communists right after the November parliamentary elections. Yet, both parties have denied such an evolution and have recently resumed the mutual attacks and the battle for the leftists’ votes.

But beyond the internal battle for the voters and the moving sands on which any partnership between the parties may function, there is the certainty that the real battle is carried by the EU/USA and the Eurasian Union/Russia. As things are looking now, one should not be worried about the geopolitical orientation of the ruling parties. Each of these is sharing, through the voices of their first- and second-level leaders, public assurances that the EU is the only reasonable path for Moldova’s future. Moreover, the leaders of all three plus one parties are doing their best to “steel” the European credits one from another. And, cynically speaking, what could that be if not a sign that their eyes and ears have turned all together towards the European partners?

Still, the big worry from this point of view is the traditional mid-positioning of the Democratic Party, who is commonly saying one thing in Brussels and another one in Moscow. Its electorate is quite heterogeneous and the party strategists are aware of the fact that the voters will follow them just due to their ”centrist” approach. That means that sliding to the left, into the arms of the communists, won’t be much worse than remaining alongside the present 99% pro-European partners. They know that their members and voters will understand and accept almost anything, in contrast to the voters of the other three center-right parties, who will certainly disapprove their parties’ eventual remoteness from the EU.

This is one of the reasons why these three parties are taking into consideration creating an electoral bloc, in order to cut the potential of eventual “renegades”. The good thing is that, as some experts argue, the only variable which is still unclear regards the speed of further European integration. The reason is that, mostly out of fear of a “Moldovan Maidan”, every government will be pro-European after the elections, even a leftist one. At least this is the view of experts such as Nicu Popescu or Oazu Nantoi.

The Association Agreement, a breath of fresh air

One of the reasons why the Democrat Party, for example, would not give up the European path too easily, lies in the integration of the European successes in their public, but also internal discourse. The signing of the Association Agreement with the EU on the 27th of June was a huge success, and any actor involved in this process would be a fool not to take advantage of this, especially in nowadays context of mass disappointment and loss of patience.

“Europeanization” got even more consistent in 2010, when the Rethink Moldova report was belabored. The document was prepared for the Consultative Group Meeting in Brussels on the 24th of March 2010 and was referring to the priorities for medium term development. It contained a brief analysis of the then recent economic developments, a reform agenda according to the European model (civil service, anti-corruption, decentralization, e-governance, among others), economic recovery, industrial parks, improving business conditions, efficient agriculture, infrastructure investments and human capital.

The progress in all these areas has served as argument when the discussions regarding the association with the EU have started. Chisinau has rapidly become the host of many European officials and some voices have begun to talk about an “European discourse inflation” inside the society. But beyond metaphors, it was an important success, upon which the ruling parties have cling on from the beginning. It was a breath of fresh air for them and for the pro-European citizens also, although too few citizens are still aware of the aims of the Agreement and its stakes.

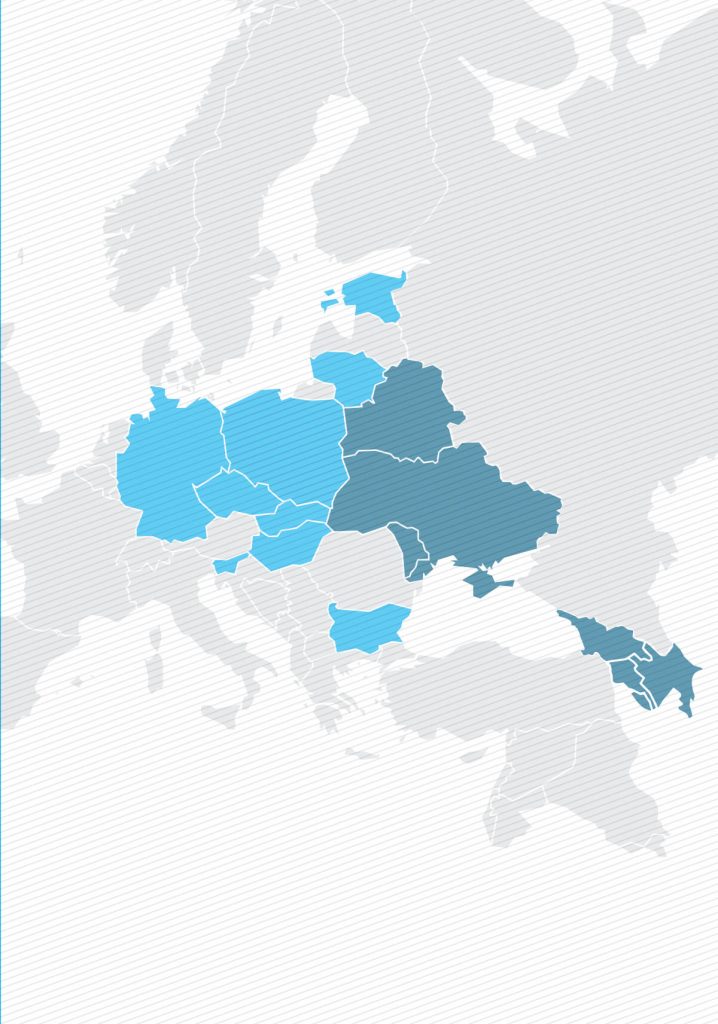

Briefly, the aims of the Agreement are as following: political association and economic integration, enhancing political relations between national and European political parties, strengthening democracy and institutional, regional and international stability, eliminating sources of security tensions, supporting the rule of law, the human rights and mobility, integrating the markets by setting up a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area. In other words, this means huge support and large amounts of resources for the Moldovans. And these are not just mere words. European countries such as Romania, Germany, Poland, Sweden, Austria, Great Britain or the Czech Republic, are among the biggest donors in Moldova.

This being the framework, the next steps should reasonably consist in implementing each and every provision described over the almost 1000 pages. But for this, political will and stability are, of course needed. It has been stated that signing the Association Agreement is the biggest achievement since Moldova’s Independence. Many analysts have argued that apart from politicians, people should be those who are setting the direction. This is why NGOs, think tanks and groups of initiative were launching campaigns, projects and all kinds of actions in order to reach the society in its depths. On the other hand, mass-media remains the main tool which intermediates this communication between these actors and the population. And the reaction of the public indicates that it mostly works.

For example, one of these think tanks, Expert-Group, has published several analyzes. These analyzes were dismantling the European integration myths, focusing on arguing why the Association Agreement is so important. The study shows that the consumers, the producers and the state will be the ones who will win, while the inefficient firms, the vested interests and the monopolist/oligopolist companies will be the losers. These materials were highly promoted in the pro-European mass-media.

The challenge of being loved by force

Unfortunately, the highly popular idiom “Moldova is not alone” has proved once again to have both positive and negative meanings. After talking about the positive ones, presenting the negative ones would be fair. We should, of course, talk about the reluctance of the Russian Federation to simply let Moldova be. And because Russia is not just a country, but the proud and “legitimate” successor of the Soviet Union, it seems also legitimate for its rulers to make use of any weapons in order to have their way in the post-Soviet space.

First of all, the economic sanctions were translated in a step by step embargo on wine (autumn 2013), meat (spring 2014) and fruits (summer 2014). Stopping tones and tones of Moldovan products at the border and leaving thousands of agricultural entrepreneurs and employees without any profit or wages, has generated enormous discontent among these categories. Knowing that Moldova is mostly an agrarian state being aware that the generalized rage would be directed towards the pro-European parties and the signing of the Agreement, Kremlin applied its economic instrument without a single blink. From that moment on, the Government realized that the real stake is not being right or wrong, but making the people see who’s right or wrong. And this will remain one of the key-stakes in the upcoming campaign.

The second instrument that was only partly used by Russia, regards the labor migrants coming from Moldova. Since regaining its Independence, Moldova was highly dependent on its migrants. Some of these went to Europe, while others to Russia. A large amount of those working in Russia are illegal migrants (as are most of the immigrants living and working in Russian Federation) who were tolerated by the authorities due to the need of cheap work force. The state institutions in Russia are well-known for acting arbitrarily, without respecting the basic rights of migrants. Plus, the lack of options for the Moldovan workers with low qualifications, or none qualifications whatsoever, has contributed to an unbalanced relation, where the workers coming from the ex-Soviet states are being completely left in the hands of the Russian authorities. The results are not at all optimistic, as more and more Moldovans are being refused while trying to enter Russia. They are being returned for all kind of reasons or for no reason at all. The aim is, on one hand, to raise unemployment and on the other, to evoke public rage while getting closer to the autumn elections. Of course, all these people blame the pro-Europeans and their attitude will hardly change, as they remain subject to Russian media propaganda.

The natural gas issue is another thorny problem for Moldova. The republic is fully dependent on the Russian gas. This means that if before the upcoming winter, Moldova does not renew its agreement with Moscow, households, public institutions, economic agents and the energy sector will not be able to function. And this would be, without exaggerating, a catastrophe. The prospects for this to happen are not very optimistic, meaning that chances for such an unhappy evolution really exist. Regardless of the present declarations or threats enunciated by Russian officials such as deputy prime-minister Dmitri Rogozin, for example, it is too soon to make inferences whether the gas will or will not be interrupted. We still need to see the reactions of the Russian Federation after the first cubic meter of gas enters Moldova through the Iasi-Ungheni pipeline coming from Romania. But we also need to see who is going to win the elections.

The last weapon against Moldova’s European path is Russia’s capabilities and intentions to re-activate territorial separatism. Both Transnistria and Gagauzia regions, alongside the “newly emancipated” county of Balti, have a recent history of conflicts or at least tensions. The Transnistrian regime is openly supported by Moscow, being artificially sustained through money and military force. It was demonstrated that without Kremlin’s support, Transnistria is nothing but a militarized buffer zone between the East and the West. It’s a no man’s land with some Russian citizens controlling the lives and resources of around 300.000 people of Romanian, Ukrainian and Russian ethnicity.

The “Transnistrian” citizenship is not recognized even by Russia. Their money called “Ruble”, similar to the Russian currency, are also useless. The thing with that territory, however, is that it is controlled by active Russian army troops and equipment, which is in contrast with the situation in the other two territorial entities mentioned above. Taking into consideration the recent worsening of the Russia-Ukraine relations, Moldovan authorities are beginning to rely more and more on their Ukrainian partners, who are equal members in the 5+2 negotiation format with Russia and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe. Until the Euro-Maidan started, Ukraine had a rather hesitating position, while everybody was hoping that it will take somebody’s side. In contrast, Transnistria is now “squeezed” between two independent and pro-European states. Consequently, it is only a matter of time for the separatist region to give up its independence claims and to choose a side.

The Gagauzia region, which is autonomous, is inhabited by around 160.000 Moldovan citizens, including 120.000 ethnic Gagauz (a Turkish orthodox population brought by the Soviets). The administrative and cultural center is the municipality of Comrat. There are, however, some centrifugal tendencies among other cities from the autonomy, which feel somehow neglected by Comrat. The capital Chisinau is also quite far institutionally speaking, although geographically there are around 100 km to Gagauzia. Luckily, getting closer to the region is becoming a strategic purpose for the Government.

Until 2009, the Party of Communists was almost totally controlling the situation, thus there was no need of intervening from outside. The anti-European discourse and the “Russification” policies were fully on the agenda. But since the pro-Europeans won the elections, things have started to precipitate. Each party from the governing coalition has tried, and still is, to gain control over the local leaders. Even the “bashkan” (governor, in Gagauz language) has a changing attitude towards Moldova’s future direction. However, it’s true that most of his public positions were anti-European until now, even though his actions are being carried on the grassroots level. Although the bashkan was not accused of anything, right before signing the Association Agreement, the Moldovan security forces have arrested two persons who were being thought to have organized anti-constitutional and military actions. The event became viral in the media, attracting all eyes on Gagauzia.

The county of Balti is the most calm among all three, but the Russian speaking minority (including many Ukrainians, ironically), is virulently against European integration. Moreover, the communist local authorities have announced several times that it is giving serious thought to organizing a self-determining referendum. Luckily, the Government has reacted in the spirit of democratic and European principles, by trying to tighten the links between the center and the north.

For example, on the occasion of City Day of Balti, the Government has provided a number of 23 trolleybuses to the citizens of Balti, using European resources from the European Bank of Reconstruction and Development. The event was conducted in the presence of the local communist authorities. We could call it a coincidence, but since then, no public threats were heard from their side. However, the electoral campaign is a perfect opportunity to revitalize their anti-European rhetoric. Regardless of their conduct, however, it is to be expected that because of their background and the influence of the Russian media, the citizens of Balti and Gagauzia will most probably vote for the pro-Russian parties, may it be the Communists, the Socialists, or the anti-European extremist Renato Usatii.

Moldova, where to? (Conclusion)

Another issue, deriving from Moldova’s Soviet past, regards its present statehood. For example, the Moldovan Parliament still relies on its legislatures from back to 1941, having its roots in an illegal act of Soviet occupation (28 of June 1940), according to the international law. This does not question its functionality, of course, but it is for sure a matter of symbolism and positioning. Actually, after condemning at the highest level the communist regime and the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact (between the Soviets and the Nazis) in the early 90’s, the back then elites did not manage to truly start all over. This is only one of the reasons why there still exists a series of voices in the public space, arguing that the statehood of Moldova is doubtful. Most of these voices are in favor of unifying with the Russian Federation (sic!), calling upon the Soviet legacy, while the others are in favor of re-unification with Romania. The armed conflict from the East of Ukraine has only reinforced both approaches, as both sides are having now enough arguments to say that Moldova is doomed as an independent state, under the threat of Russia.

The option of unifying with Russia is aberrant for now, at least as long as Russia does not go further for the South of Ukraine in the Odessa region. Under the influence of Russian media, many Moldovans think Americans and Europeans are the source of the conflict. The Eastern message was unequivocally stating, since the beginning of the Euro-Maidan, that the West organized all the menace, manipulating all the Ukrainians to go against their “Slavic brothers”. It would be hard, considering this, to expect that after months and even years of cultivating the admiration for Vladimir Putin’s aura and power, the category of Moldovans I am speaking about here, will change their minds at a glance. The force of habit is something the Moldovan society still has to fight with. And in such times, when its neighbor is being occupied by foreign military troops and a great deal of Moldovan citizens are dreaming of being conquered by the same foreign troops, fighting bad habits can become vital.

On the other hand, re-unification with Romania is geographically possible, but merely impossible because of other reasons. It should not be a matter of worry for the western partners and for the Russian occupants. The reasons are quite simple and could be listed as following.

First of all, there is a need of social consensus, so that the majorities from both Moldova and Romania vote in favor of the re-unification at an eventual referendum. The polls show that even if the citizens of Romania would vote in favor, the Moldovan ones are far from the thought, around 1/4 of the respondents agreeing with this direction for their state. Secondly, none of the present parliamentary parties have the re-unification process in their political program. The closest thing is Liberal Party’s and Liberal Reformist’s Party center-right discourses regarding national identity, but limiting themselves at identity issues, without touching the subject of border modification. And thirdly, both Moldova and Romania do realize that the more Moldova approaches the EU, the more the re-unification is beginning to look like an unnecessary complication.

However, most of the Moldovan citizens are in favor of a true independence for their state. Unfortunately, many Moldovans put the EU in the same pot as NATO, without having a proper understanding of what each of these organizations really means. These kinds of misinterpretations are being stimulated periodically by populist public actions having no reasonable basis, organized by pro-Russian interest groups. For example, recently, during the NATO summit in Wales, the Party of Socialists organized an anti-NATO protest in Gagauzia, having 20 persons protesting against Moldova participating in NATO missions. Meanwhile, Moldova was being accepted in the Defense and Related Capacity Building Initiative. The event was reported as a major success by the Moldovan Defense minister, Valeriu Troenco. Soon after this, a comprehensive analytical study and specific support in the necessary areas are expected to follow.

Too few Moldovans are pro-NATO at this moment. The proportion is reaching about 25%, according to several not so recent polls. In the same time, about 55% of the population is pro-EU. However, the events in Ukraine have changed considerably the attitude of those rather neutral Moldovans, who were oscillating or who did not have any outlined attitude towards the Alliance. Having no recent and reliable sources to refer to, some influent pro-European media sources have recently conducted online polls, showing a huge majority of respondents being pro-NATO. But from a sociological point of view, this is also unreliable data.

It is worth mentioning that supporting the Ukrainian people in their striving for freedom and democracy became a massive phenomenon, being embraced by all the pro-Europeans from Moldova, but first of all by the Government and the pro-European parties. It has equally comprised those inside the country, as well as those included in the European Diaspora. The solidarity was being manifested through social networks, mass-media and throughout the internet. Unfortunately, the Diaspora working in Russia remains silent, just like before.

The article was originally published in the first issue of “4liberty.eu Review” entitled “The Eastern Partnership: the Past, the Present and the Future”. The magazine was published by Fundacja Industrial in cooperation with Friedrich Naumann Stiftung and with the support by Visegrad Fund.