The use of participatory budgeting (PB) has appeared in more and more democratically governed municipalities in recent years. According to the 2021 book “World Atlas of Participatory Budgeting,” this method is widespread primarily in Europe and secondarily in South America, in which the residents of the city can propose the use of a certain amount from the municipality’s budget.” The tool, which is mainly used at the municipal level, not only promotes the highest possible level of involvement of residents in public affairs that affect them, but also ensures the transparency and openness of decision-making.

Participatory budgeting is not only important in urban development, but is essential in the development and growth of (local) democracy. The active role of voters in everyday political life is the most effective way for political representatives to actually deal with problems that frustrate the population the most. Decision-making at the national or international level often takes years and is not necessarily effective in solving smaller, local problems, even if the actors in political life have the common good in mind. Participatory budgeting solves such and similar problems, both in Budapest and in other large cities in Europe and elsewhere in the world.

International Background

Brazil, one of the world’s largest and most populous countries, faces unique challenges in everyday politics. One of these is how to represent hundreds of millions of people equally and democratically. In 1989, the Brazilian Workers’ Party attempted to find an answer to this question by introducing participatory budgeting in the city of Porto Alegre, in the south of the country. At that time, about a third of the city lived in extreme poverty, without access to basic needs such as clean drinking water, public sanitation, or medical facilities. Since the introduction of the new decision-making method, 99% of the territory has received access to drinking water; the availability of sanitation and public health services has increased to 86%; and more than 50 new educational institutions have been built.

It is no wonder that the vast majority of European cities have taken up similar initiatives. Understandably, from a geographical and cultural perspective, Lisbon and Madrid quickly adopted the good practices of Brazilian leadership; Paris and Amsterdam were quick to follow with the introduction of participatory budgeting. In Central Eastern Europe (CEE), Poland, among others, was the pioneer, representing the countries attempting to democratize in the late 1990s and early 2000s after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Poland, Hungary, and several other countries in the region have found themselves facing a unique democratic crisis in these times. Countries that wished to introduce democratic practices, but had no previous stable democratic foundations to build on, faced unexpected problems in these times, such as distrust and a crisis of confidence in each other and in the country’s leadership, or the newly emerging demand for increased transparency in political processes. Hungary, and Budapest and its leadership in particular, are facing these and similar problems and demands today.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that the year 2020 and the period after it – as the 2021 book discusses in detail – presented the world’s political leaders with special challenges due to the COVID pandemic, which also had a major impact on the operation and use of participatory budgeting. The pandemic greatly influenced the political situation of most countries, starting with postponed elections, through the adverse effects of isolation, to the extraordinary and radical change in demographic distribution.

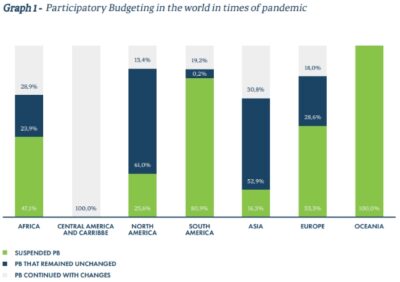

Last but not least, the actions of leaders with populist and autocratic tendencies during the pandemic and immediately after must be taken into account, since in extraordinary cases (pandemic, world war, etc.), the current government can decide in favor of emergency governance, thereby authorizing politicians and other decision-makers to govern a city or country without checks and balances. As the graph shows, during COVID-19, 53% of participatory budgeting projects and elections in Europe were suspended, and only 28% were able to continue with minor or major changes (for example, by moving elections online).

Chart 1: Participatory Budgeting in the World during the Pandemic

Ideas and Processes in Budapest

Like many other large cities around the world, the city government of Budapest began to take the use of participatory budgeting more seriously in 2020/2021. And for good reason: in the years after the first votes were cast, more than 90% of the 2020-2021 projects have already been implemented, with the remaining projects being under implementation. The capital has already completed 78% of the 2021/2022 projects, while more than half (56%) of the winning projects for the 2022/2023 period are already available to city residents. From the winning projects of the past two years, all are currently under implementation.

The popularity of the project is also proven by the fact that the capital’s leadership receives an increasing number of project ideas every year. Partly for this reason, and partly with equal opportunities in mind, the capital recently introduced quotas in order to ensure that one type of project does not enjoy an overwhelming advantage over other categories. The three most requested idea types can start the vote with a maximum of 75 proposals each – these topics are Environmental Awareness, Greening, Climate Protection, Social Care, and Culture, Community, Sport. The second most popular quota is made up of elements of Cycling Transport Infrastructure, with a maximum of 40 ideas, followed by Elements of Pedestrian Transport Infrastructure and Public Toilets, with a maximum of 25 and 10 ideas, respectively.

Within the institutional framework, the professional departments of the Budapest Municipality deal with the budget review, together with, in the case of applications submitted for specific areas, the representatives of district municipalities. During the proposal process, both the proposer and the project staff must constantly keep in mind the values represented by the capital, which are “equality, community approach, quality change, functional adequacy, safety, sustainability, and likability”. Emphasizing this, the received project proposals are checked by the Social Cooperation Department before the city administration publishes them on the website.

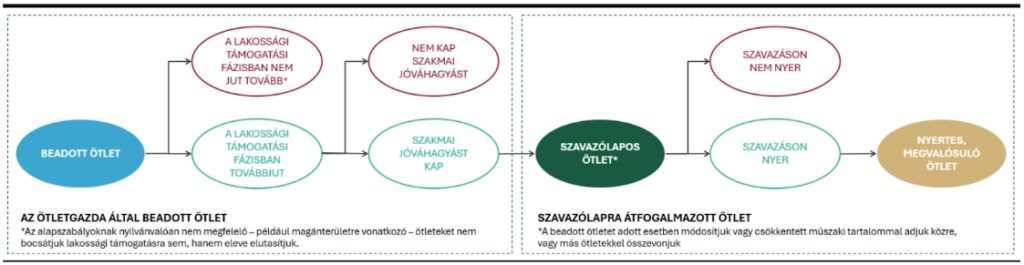

The application process is simple. Anyone who lives, works, or studies in Budapest and is over 14 years old can submit one or even more applications after registering on the website (it is enough to declare the aforementioned data; no verification is required). After the official check (compliance with the requirements and guidelines), the public support phase introduced last year follows, which is essentially a pre-selection, where an unlimited number of projects can be supported, and from which the 300 most popular ideas advance to the professional review phase. This is due to the increased number of proposals submitted over the years, which entails a lot of extra work for the capital’s staff.

During the professional evaluation, aspects such as feasibility within the capital’s financial framework, compliance with the applicable regulations (architectural rules, legislation), or compatibility with the plans of the given municipality are taken into account. The flowchart below explains this.

Figure 1: Participatory Budgeting Ideas Flowchart

Voting, similar to the application, is available to all Budapest residents, employees or students over the age of 14, online on the website or at designated voting points, such as libraries. The voting is divided into 5 categories; a maximum of 3 projects can be selected in each category. The categories are Local Large Ideas; Local Small Ideas; Open Budapest; Green Budapest; and Opportunity-Creating Budapest. The community budget can be managed from one billion forints, and this is divided between the 5 categories: 120 million forints each go to Open, Green and Opportunity-Creating Budapest categories; 400 million to the Small Ideas category; and 240 million to the Large Ideas category.

Results, Impacts and Good Practices

The success of the project is reflected in the increasing participation of the population year to year, and the increase not only in the number of voters, but also in the number of initiators and applications uploaded. The effects of the initiative are clearly positive: in contrast to the often extremely slow implementation and difficult adjustment to complicated bureaucratic processes common at the national and international levels, participatory budgeting projects decided and implemented at the municipal level are fast, efficient, and actually address the problems that preoccupy the majority of the population.

Some good practices that are missing from the community budgets of other European cities compared to Budapest are thematic voting by category, which facilitates the efficient assessment of similar ideas; the quota system ensuring equality, which contributes to the fair representation of all residents of the city; and public support; which, by fulfilling a pre-voting function, reduces the burden on overworked employees of the capital. To facilitate all this, the submission of ideas, public support and voting are also available online and only take a few minutes. Last but not least, in order to avoid difficulties, the personal data provided does not need to be verified in any form, only the declaration is required.

Conclusions

All signs point to the fact that the participatory budgeting method is becoming more widespread in Europe and beyond. Exercising the autonomy of large cities is just as important for democracy as going to the polls every four years. In order to increase community building, transparency and a sense of trust, it is important that the interests of city residents are properly represented.

In addition, the growing tendency of people to expect instant solutions can be mitigated by the speed and efficiency of municipal decision-making and project implementation. If the larger part of the population becomes an active participant in the definition of the community budget (for instance, the more people vote for their favorite initiatives or the more people submit ideas for city development), the more satisfying their political representatives can do their job – with them and for them.

Bibliography

https://medium.com/updating-democracy-rebooting-the-state/case-study-participatory-budgeting-in-brazil-9b7c48290c29

https://oostbegroot.amsterdam.nl/oudoost/english

https://oostbegroot.amsterdam.nl/oudoost/stemmen#

https://otlet.budapest.hu/oldal/bovebben-a-kozossegi-koltsegvetesrol

https://otlet.budapest.hu/projektek?campaign=1&status=ready

https://resources.illc.uva.nl/illc-blog/when-residents-design-their-city/

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/391274488_World_Atlas_of_Participatory_Budgets_202021

https://www.resilience.org/stories/2025-03-18/participatory-budgeting-includes-community-members-in-the-public-funding-process/

https://www.sdg16.plus/policies/participatory-budgeting-brazil/

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/07352166.2025.2480806#d1e160

Continue exploring:

Is Simplification Enough? In Conversation with Martin Vlachynsky [INTERVIEW]