Prior to the crisis triggered by the COVID-19 outbreak, the Lithuanian economy had been enjoying a rapid growth. Yet, while the number of available jobs had been increasing, the number of unemployed had remained steadily high.

The reasons for this may have been twofold: (1) government-funded measures aimed at retraining and professional reorientation of workers and jobless people were targeted and implemented properly; and (2) people lacked motivation to join the labor market. This study analyzes the latter reason in greater detail.

DOWNLOAD FULL REPORT [IN PDF]

The motivation and willingness of unemployed people to work, rather than survive on social benefits, is reflected in the “unemployment trap” indicator, or the level of income received by a jobless person in benefits, as a share of the individual’s potential income from employment.

The wider the unemployment trap, the less attractive and beneficial it appears for people to earn a living by joining the labor force.

When the unemployment trap is high, the opportunity costs of employment are too high: a person finds it more beneficial to simply continue living on social welfare and remain unemployed. While short-term unemployment is mainly an economic problem, long-term unemployment becomes a social concern. People who remain unemployed for a long period of time lose their social skills and are especially vulnerable to different addictions and mental health problems.

A job is the main way to ensure a decent living and well-being. Unemployed individuals lose opportunity of social mobility. Their expectations of being fairly assessed and accounted diminish, and motivations shrink even further. This creates a vicious circle of income inequality, because inequality cannot be reduced without a motivation to work.

A more general issue evolves as the unemployed may join the shadow economy to supplement their benefits. Although the unemployment trap among the lowest-wage earners had shrunk slightly prior to the COVID-19 crisis, this reduction was so small that the incentives for people to take up employment remained low.

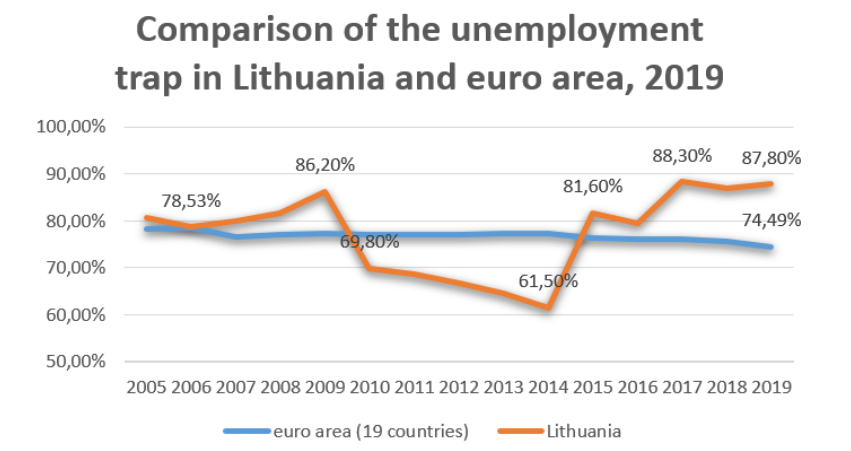

For comparison, in 2019 the unemployment trap in Lithuania stood at 87.8 percent, compared to the euro area average of 74.5 percent.i The general trend is unfavorable: over the last year the unemployment trap has grown by 1 percentage point.

1. The number of job vacancies is not going down. Neither is the number of long-term unemployed

After losing their jobs, many individuals face psychological difficulties, lack social relationships, and are unable to implement their capabilities. Studies suggest that the unemployed are the group most likely to experience psychological problems. Unemployment also slows down a country’s economic growth, reduces people’s income, and increases public spending.

It is, therefore, especially important that unemployment be properly managed. According to Eurostat, the European Statistical Office, in 2019 the employment rate in Lithuania exceeded the EU average by 5.1 percentage points, with 78.2 percent of the total population aged 20–64 being employed.

Although the employment rate in Lithuania was higher than the EU average, it still lagged behind such countries as Estonia, Czechia, Germany, and Denmark.

Rapid economic growth has created an increasing number of new jobs in Lithuania. At one point, the unemployment rate went down, while the number of job vacancies increased. Quite often, however, companies have suffered from a lack of suitable applicants.

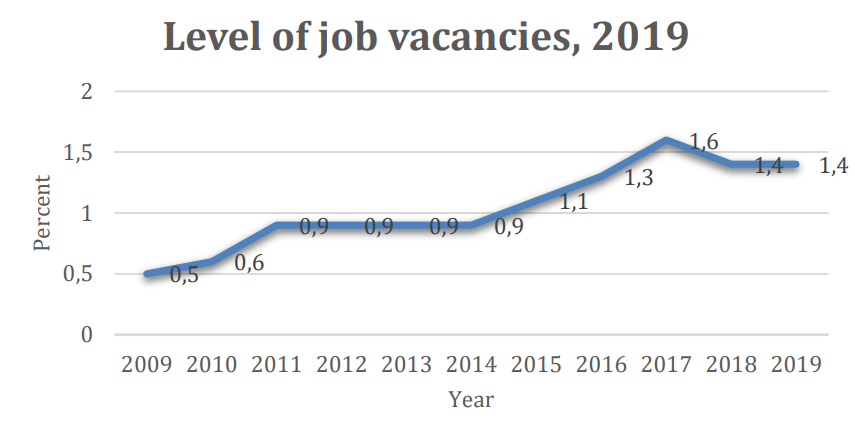

In particular, it has been hard for employers to find the necessary specialists in the country’s regions. The figure 1. represents changes over time in the level of job vacancies across Lithuania.ii The indicator represents a ratio between job vacancies and overall workplaces.

Figure 1.

Although difficulties in filling vacancies usually signal the failure of the labor market to match the needs of the growing economy, as well as an inadequate level of retraining and a lack of motivation to work, they are also the result of a general decline in the size of the country’s population.

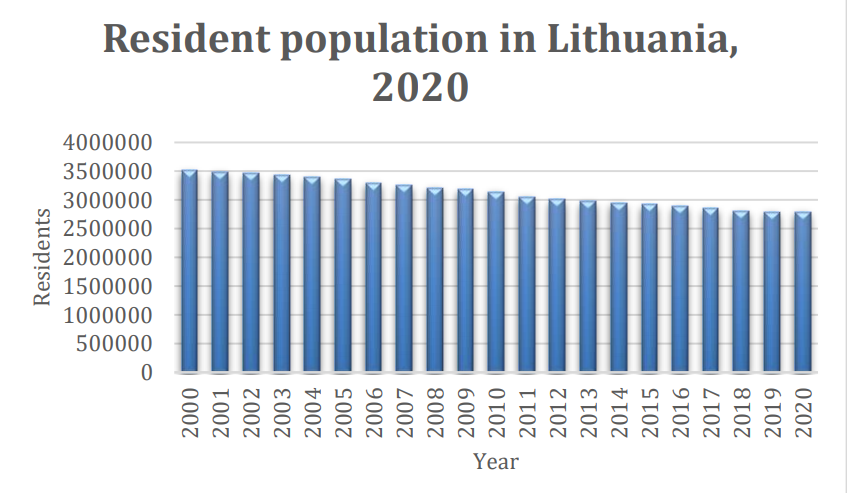

The figure 2. illustrates changes over time in the Lithuanian population. Over a twenty-year period, the population of Lithuania has decreased by nearly 720,000.iii This has resulted in a range of social problems, as well as slowing down economic growth, and has led to an even greater tax burden being imposed on those in employment.

In the context of such trends, it is even more important for people to possess the motivation, competencies, and empowerment to work.

Figure 2.

The problematic situation of the labor market in Lithuania is also evidenced by the number of long-term unemployed (those unemployed for a year or longer): in Q4 2019, the long-term unemployment rate remained almost unchanged compared to 2018 and stood at 1.9 percent.

During that year, the number of long-term unemployed increased by two thousand to 30,300—nearly one-third of all those unemployed.iv With child benefits having been further increased this year, judging from the Polish experience (which is further discussed below), it can be predicted that the number of long-term unemployed will continue to grow in the long run.

This gives rise to multiple threats: supporting an increasing number of long-term unemployed is not only a burden on the employed, but also represents a great misfortune for the unemployed themselves: their competencies, skills, and social relationships are lost, and it becomes harder to reintegrate into the labor market after a prolonged period of time.

Measures must be sought that can offset the situation, along the reintegration of the long-term unemployed into the labor market—or at least, a reduction in the number of the newly unemployed.

In a bid to compete with other employers, companies increasingly offer a signing bonusv to attract new workers. This covers, for instance, income losses incurred by new employees after they leave their previous employer, without raising the general level of wages within the company.

Wider use of signing bonuses at the national level might help, at least partially, to deal with the issue of the long-term unemployed. Those receiving benefits might be motivated not to wait for monthly benefits paid by the state, and choose instead to receive a one-time bonus immediately after finding a job.

After receiving this bonus, workers will be obliged to work for that employer for a specified period of time. Bearing in mind that as many as 30 percent of all those unemployed are long-term, such a measure would provide a strong incentive for them to reintegrate into the labor market.

Signing bonuses could be paid from the budget of the State Social Insurance Board and could be financed by reducing the length of time for which unemployment benefit payment is paid. This would result in a win–win situation for all: job vacancies would be filled, the unemployed would return to the labor market more quickly, and the state would more frequently avoid paying unemployment benefits for the entire period of nine months.

This incentive scheme could also include partners helping to enable employment, such as employment agencies and others. These partners would have a financial interest in the long-term unemployed finding a new suitable job.

The involvement of such partners would help the unemployed overcome the inertia that confines them. It would also provide them with the professional knowledge, job skills, and social experience required to reintegrate into the labor market.

The signing bonus is likely to encourage the unemployed to look for a job, and to take up employment as soon as possible instead of waiting for nine months while unemployment benefits are paid. As such, signing bonuses could become an efficient measure to support and increase people’s motivation to work.

2. The unemployment trap in Lithuania exceeds the euro area average

The unemployment trap is a relative indicator that represents the level of social benefits received as a share of the potential income an unemployed person could earn if they took up employment.vi

Three values are used to calculate the level of the unemployment trap: the person’s potential net wages and gross earnings, as well as the level of unemployment benefit.vii

For example, if a single person is likely to be employed for minimum monthly wage, to calculate the unemployment trap in which the person is caught during the first months of unemployment, three figures must be entered into the formula: gross earnings (607 EUR), net wage (around 437 EUR), and the unemployment benefit they would receive during the first three months (around 357 EUR).

In this case, the individual faces an unemployment trap amounting to 86.8 percent. The higher the percentage, the less worthwhile it is for the person to get a job, because unemployment and other social benefits constitute a larger share of the income that the worker might earn through working.

According to Eurostat, in 2019, the unemployment trap in Lithuania amounted to 87.8 percent compared to an average across the euro area of just 74.5 percent.viii The high level of such an indicator reveals that unemployment benefits constitute nearly 88 percent of an unemployed person’s potential earnings through employment.

Meanwhile, unemployment benefits within the euro area amount to approximately 75 percent of the potential wage—around 13 percentage points lower than in Lithuania. The unemployment trap across the euro area is much more stable than it is in Lithuania, and has already been decreasing for some time.

In Lithuania, by contrast, the trend remains upward. Consequently, the motivation to work of a jobless person in Lithuania is on average more than a tenth lower than that of their average European counterparts.

Figure 3.

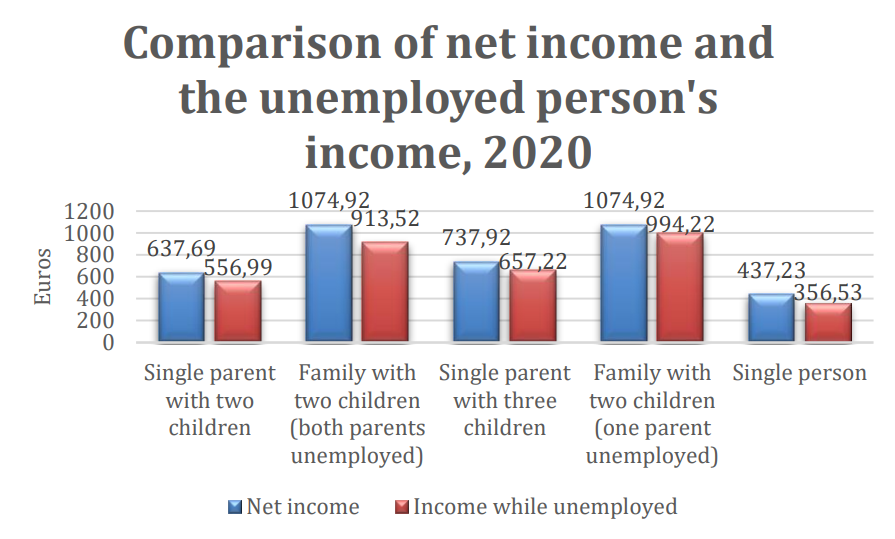

Single parents and large families with parents earning minimum monthly wage are at greatest risk of being caught in the unemployment trap.

For example, we will consider the case of a family with two children in which both parents earn a minimum monthly wage, i.e., a net wage of 437 EUR. One of the parents loses their job or decides to quit in order to dedicate more time to home and family. During the first three months while one parent is unemployed, the family will only lose around EUR 80 each month compared to its former income.

In this case, the unemployment trap will be as high as 94.3 percent. In other words, if the parent who lost their job starts working, the family’s income will only increase by 5.7 percent.

To enable comparison, several other examples of families’ total monthly income from employment vs. total income while unemployed are provided in the figure 4. In all examples, parents earn a minimum monthly wage.

Figure 4.

Source: Lithuanian Free Market Institute

Source: Lithuanian Free Market Institute

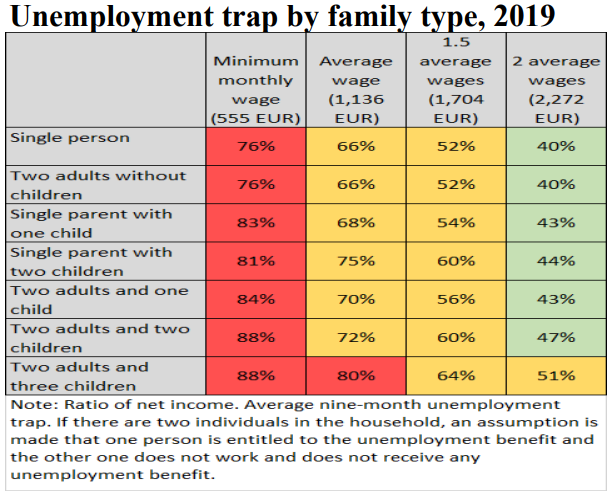

The unemployment trap is also analyzed in the Survey of Indicators of Monetary Incentives to Work 2019 conducted by Lithuania’s Ministry of Social Security and Labor.ix According to the survey, the unemployment trap is best assessed on a household basis because money earned by family members is usually spent together, as presented in Figure 5.

Due to the fact that the amount of unemployment benefit changes depending on the duration of its payment, researchers have calculated the unemployment trap over an average period of nine months. It is obvious from this table that all family types encounter a high level of unemployment trap.

According to the study, the unemployment trap is highest in those households where wage earners received minimum monthly wages prior to losing their jobs.

Among those households in which a single wage earner earned the equivalent of two average wages, the motivation to remain unemployed is low: the unemployment trap amounts to just over 40 percent.

Nevertheless, bearing in mind the free time available to unemployed people, and the potential alternatives for using it, the motivation not to work still exists even among individuals with this level of income.

Figure 5. Unemployment trap by family type, 2019

Source: Survey of Indicators of Monetary Incentives to Work 2019, Lithuanian Ministry of Social Security and Labor

Source: Survey of Indicators of Monetary Incentives to Work 2019, Lithuanian Ministry of Social Security and Labor

The Survey of Indicators of Monetary Incentives to Work 2019 emphasizes that when both parents are employed, the income of families with two or more children increases on average by just 12 percent, compared to a situation in which neither adult works and one of them receives unemployment benefits and other benefits payable to the family.

Even if one of the adults in the family could potentially earn the equivalent of 1.5 average wages, all types of family would still encounter an unemployment trap higher than 50 percent.

This means that the unemployment benefit they used to receive constituted more than half of their potential income from work. The researchers summarize that high level of unemployment trap indicators is determined by the size of the unemployment benefit and other means-tested benefits received along with it, such as child benefits.x

The level of the unemployment trap is also increased by the amount of taxes deducted from the working wage. Upon employment, the person pays social insurance contributions and personal income tax.

It turns out that when working for a minimum monthly wage, the amount of income received is higher than the threshold for the receipt of means-tested benefits: the family loses the increased child benefit, free school meals, and various other benefits that increase the family’s standard of living.

According to the survey of indicators, the unemployment trap is higher among those people whose potential income is lower. This reflects the progressive design of unemployment benefits, i.e., the existence of a fixed basic share of the benefit and the cap applied to the maximum amount of the benefit.

As a result, unemployment benefit compensates a much greater share of a person’s wage in cases where the person’s previous income was lower. The study concludes that in order to increase incentives to work among those individuals who are likely to be employed for a lower wage, the fixed share of unemployment benefit should be abolished or reduced.

While the authors of the study provide suggestions as to how the unemployment trap might be reduced, it is still not fully clear at what level the unemployment trap should be set, and by how much it should be reduced. According to the authors, it would be possible to achieve this by revising the regulations governing the payment of the unemployment benefit.

At the same time, they emphasize that the unemployment benefit has decreased over time and that, as a result, people are automatically encouraged to take up employment as they approach the end of their period of unemployment benefit.

The authors of the study carried out for the Ministry of Social Security and Labor do not believe that the benefit period is too long.

At the same time, they emphasize that the level of poverty in Lithuania is among the highest in the EU, and in 2017 was as high as 62 percent among the unemployed.

3. Factors underlying changes in the unemployment trap

The unemployment trap is raised or lowered when a change is made to one of the variables in the formula used to calculate it. Unemployed who are likely to get a job for a minimum monthly wage are the group most often caught in the unemployment trap.

Both the level of unemployment benefit and the levels of net and gross pay for those receiving the minimum monthly wage are the result of political decisions. Unemployment and other benefits, as well as exemptions for the unemployed, are set by politicians.

It should also be noted that the unemployment trap is heavily affected by taxes too. The high level of unemployment trap faced by the lowest-earning portion of the population is a sign of disproportionally high taxation on the lowest-earning workers.

Thus, it is clear that decisions taken by the government underpin any increase or decrease in the unemployment trap.

At first sight, the unemployment trap might appear to shrink when the minimum monthly wage is raised. In 2020, the net minimum monthly wage increased from EUR 396 to EUR 437, while unemployment benefits went up to nearly EUR 357 (an increase of more than EUR 12) during the first three months of unemployment, provided the claimant earned the minimum monthly wage before becoming unemployed.

At the beginning of 2020 (prior to COVID-19 crisis), the unemployment trap amounted to 86.7 percent during the first three months of unemployment. This represents an improvement compared to the end of 2019, when the unemployment trap for those likely to be employed for a minimum monthly wage stood at 90.7 percent during the same three-month period.

Due to the increased minimum monthly wage, the motivation to work among the lowest-earning portion of the population increased by 4 percentage points. This year, the four-member family with two children mentioned earlier (in which both parents earn the minimum monthly wage) would on average lose nearly EUR 81 per month, if one of the parents lost or decided to quit their job.

In 2019, they would have lost only around EUR 50 per month during the first three months of unemployment.

Nevertheless, it is worth noting that unemployment benefits are calculated on the basis of the average monthly insured income earned during the thirty months until the final month in work before the individual registered with the employment service.

As time goes by, the higher minimum monthly wage will gradually feed into the average monthly wage used to calculate unemployment benefits, and these benefits will go up too—negating the improvement achieved in the unemployment trap. Eventually, the unemployment trap, which was lower immediately after the increase in the minimum monthly wage, will return to more or less its original same level.

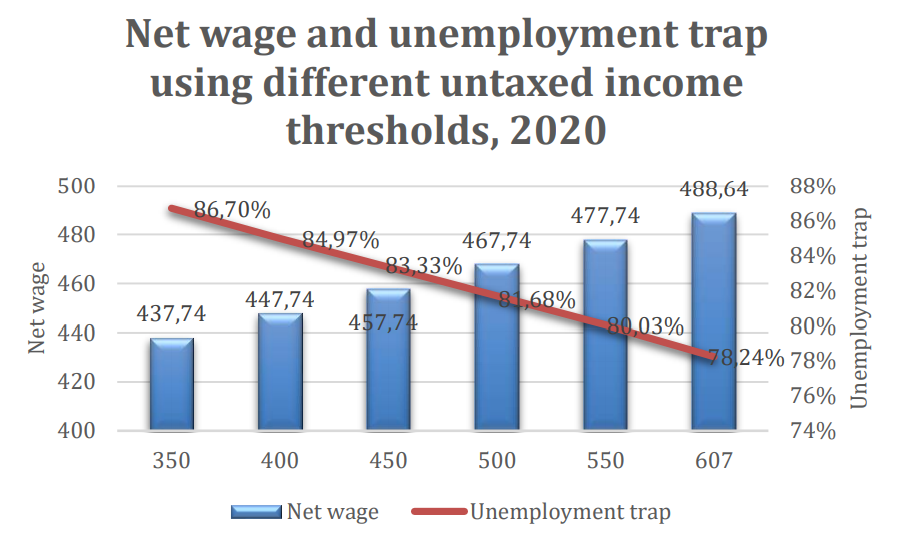

The unemployment trap could also be reduced by raising the threshold above which income becomes taxable—and unlike an increase in the minimum monthly wage, raising the threshold for untaxed income would produce a long-term reduction in the unemployment trap. The untaxed income threshold is the amount below which wages are not subject to personal income tax.

Currently, the untaxed income threshold is EUR 350. This means that an individual working for a minimum monthly wage receives EUR 437.74 after taxes. If the untaxed income threshold were raised to EUR 400, the individual’s net wage would increase up to EUR 447.74.

In this way, the tax burden on the worker can be reduced, enabling those who work to benefit from higher real net income, without triggering a corresponding rise in the level of unemployment benefit.

Indeed, if the untaxed income threshold were increased by EUR 50, the unemployment trap for the lowest-earning population would go down by nearly 2 percent.

If the untaxed income threshold were increased to the same level as the minimum monthly wage (currently EUR 607), the net wage would increase up to EUR 488.63, while the unemployment trap for workers earning the minimum monthly wage would go down to 78.24 percent.

Such a reform could bring the unemployment trap in Lithuania down to the euro area average, and at the same time boost the motivation to work by means of an actual increase in income, rather than by cutting benefits.

Figure 6.

Source: Lithuanian Free Market Institute

Source: Lithuanian Free Market Institute

After the financial crisis of 2007–08, a significant reduction in the unemployment trap was observed in Lithuania. To manage the crisis, austerity policies were implemented that cut public expenditure. Unemployment social insurance benefits were targeted first.

As of January 1, 2010, the maximum benefit was reduced by 38 percent, from LTL 1,042 (EUR 302) to LTL 650 (EUR 188), while unemployment benefits went down to an average of LTL 550 (EUR 159) per month.

Conditions for the payment of unemployment benefits were tightened too: the share of unemployed people receiving unemployment benefit decreased from 34 percent at the beginning of 2009 to 15 percent at the beginning of 2011.

The above measures led to a reduction in the unemployment trap and higher motivation among workers to reintegrate into the labor market after losing a job, rather than choosing to receive unemployment benefits.

When cutting unemployment benefits, however, it should be borne in mind that this money is collected into the state budget in the form of the unemployment social insurance tax, and the level of benefits should be sufficient to meet the minimum needs of those who have lost their jobs.

Drawing on the experience of foreign countries, motivation to work is greatly affected by the level of unemployment and child benefits. To mitigate the consequences of the financial crisis of 2007–08 and to assist people who had lost their jobs, most states in the United States extended the period for which unemployment benefits were paid.

Between 2011 and 2013, this extension was abolished in the majority of states. As a result, by 2014, the employment rate had increased by 25 percent. The employment-to-population ratio went up too. Thus, reducing the period for which unemployment benefits are paid is an effective measure in reducing the unemployment trap and encouraging people to work.

To manage the financial crisis of 2007–08 in the United States, the allocation of child benefits was in all cases linked to parents’ income. In the next chapter of this paper, we provide more information about why the introduction of non-means-tested benefits such as child benefits does not create incentives to work.

In 2020, Lithuania faced a crisis triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic. The extent of its adverse consequences will depend on how quickly the pandemic is managed, and how justified and effective the measures employed to curb the spread of the virus and restrict people’s activities will be.

The most positive scenarios for Lithuania’s economic development predict that the Lithuanian economy could shrink between 1.3 and 7.3 percent during 2020, while GDP may even grow between 2.2 and 6.6 percent during 2021.

It is projected that the unemployment rate in the country will rise temporarily from 8.1 to 10.5 percent in 2020, while the number of those employed will shrink between 2 and 4.5 percent.xi

As a result of a lower GDP and an increase in unemployment, average wages are also expected to fall. Public institutions aim to implement measures that will help those who have lost their jobs to survive until they find further employment.

The unemployed will be entitled to a temporary job-search allowance even if they are not currently entitled to unemployment benefit. For those who do not receive unemployment benefits, the temporary job-search allowance will amount to EUR 200; in cases where the unemployment benefit is already being received, an additional EUR 42 per month will be paid for a period of six months. Job-search allowance is expected to be paid to around 195,000 people.

Although it will ensure they receive a higher income, it will also increase the unemployment trap. The reduction in average wages and increase in social benefits received while unemployed will lead to stronger disincentives to seek work.

Consequently, although the job-search allowance is temporary, and is intended for maintaining a person’s standard of living as well as promoting consumption, it will further reduce the motivation of jobless persons to reintegrate into the labor market.

It is worth noting that the calculation of the unemployment trap does not take into account all exemptions available to deprived people who have lost their jobs. The children of such individuals are entitled to free school meals; their families can benefit from lower heating rates; in addition, they do not require child-care services, if there are small children in the family.

In general, the unemployed have more free time which may be used for household chores, child care, or other activities that can even constitute a source of additional income.

In reality, therefore, the unemployment trap is much higher than shown by calculations, because the family draws additional benefit from various exemptions and due to the additional time they have at their disposal.

4. The implications of child benefits on the unemployment trap

A high unemployment trap is not simply the result of relatively generous unemployment benefits. Child benefits, so-called “child money,” also serve as a disincentive to work. The original aim of child benefits was to meet the most urgent needs of those whose income is insufficient, as well as stimulate, in part, the birth rate. In reality, however, they have contributed to the disincentive to work.

The major problem with child money is that it is impossible to ensure that the benefit is actually spent on children—therefore, it simply supplements the family’s total income, and parents do not have to make any effort to earn it.

The amount of child money paid to more deprived families is larger by EUR 50, provided the family’s income does not exceed EUR 250 per person. As a result, the motivation of more deprived parents to join the labor market is reduced still further (and, as we know, the unemployment trap is highest among the most deprived).

In response to the intended increase in child money in 2020, at the end of 2019, Biržai district municipality expressed its position that the current national policy for family support is flawed and does not stimulate employment. The council, therefore, suggested changing the procedure for the payment of child benefits.

In the Post-Quarantine Support Plan approved by the government, among other measures, changes were planned to the payment of child benefits. By April 1, 2020, an additional EUR 100 was paid to disabled children as well as to children from large or deprived families.

According to the methodology used by the Ministry of Social Security and Labor, a deprived family is defined as one in which the average monthly income per family member (not including child money and a portion of wages) does not exceed EUR 250 over a period of twelve months.

As of April 1, a new procedure came into effect, under which income earned during the previous three months, rather than twelve, is taken into consideration.

As a result of many people losing their jobs during quarantine, or having their income reduced, larger amounts of child money will be paid to around 33,000 children. Such changes will remain effective for six months after the end of quarantine.

Although this measure will increase income for families that have faced difficulties during the crisis, it will also increase the unemployment trap, and people will be less motivated to reintegrate into the labor market.

So-called “child money model” is also distributed in Poland. In 2016, a program of benefits named Rodzina 500+xii was launched to provide for each family’s second (and every subsequent) child. The main objective of the measure was to improve families’ financial situation and increase the country’s birth rate.

The program ensured monthly support of PLN 500 for each second and subsequent child until they reach the age of eighteen. This child benefit is also allocated for the first child, provided the family’s income per person does not exceed PLN 800 (or PLN 1,200 if the child is disabled). Unlike Lithuania’s child measures, the benefit for the first child is completely withdrawn if the per-person threshold for the family’s income is exceeded.

It is also worth noting that at the time when child benefits were introduced in Poland, they constituted nearly one-third of the net minimum wage; in Germany, by comparison, they represent only 12 percent. At the present time, the minimum wage in Poland is higher, and the child benefit constitutes around one-quarter of the minimum wage.

These direct payments to families, disproportionally high in comparison with wages, were intended to promote an increase in the birth rate and a reduction in poverty. In reality, the results were very different from what was expected.

By the middle of 2017, the participation in the labor market of mothers who were raising children had fallen by 2.4 percentage points. The effect was even greater among less-educated women residing in small towns.

Later, in 2018, Poland’s birth rate even went down. The introduction of child money in Poland not only failed to increase the birth rate, but actually encouraged around one hundred thousand women to withdraw from the labor market.

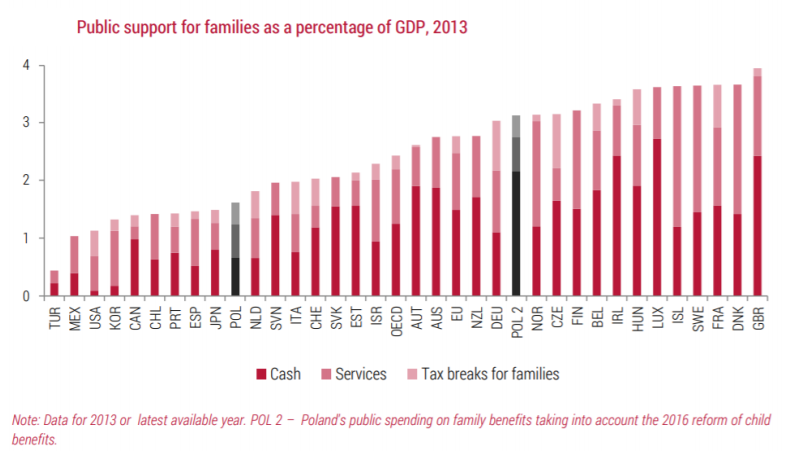

Prior to the launch of the Rodzina 500+ program, Poland’s system of support for families was fairly modest. The new child benefits nearly doubled the direct support received by families, and support for families in Poland is now much higher than the OECD average.

Direct payments are among the highest in Europe, only lagging behind such countries as Luxembourg, the United Kingdom, or Ireland. Unsurprisingly, this places a huge burden on state finances, with public support for families accounting for more than 3 percent of the national budget.

Figure 7.

Source: OECD Family Database, 2017

Source: OECD Family Database, 2017

The Polish example demonstrates that child money distorts family motivations and constitutes a disincentive to work. With similar trends appearing in Lithuania, it may be expected that the same effects will be experienced here.

Direct payments, which in Poland are among the highest in Europe, have not only pushed thousands of people away from the labor market, they have also failed to achieve the key aim of increasing the country’s birth rate. Benefits become an excessive burden for the state when resources could be allocated in a more targeted manner—for instance, on quality education or health care.

5. Unemployment and the shadow economy

In many cases, people choose not to work and have more time to dedicate to their home or children. Bearing in mind the scope of the shadow economy in Lithuania—particularly in relation to small-scale operations—the motivation for unemployed individuals to live on benefits and supplement their income through the shadow economy is greater than is shown by the unemployment trap.

It is claimed that the shadow economy in Lithuania represents between 13 percent and 26 percent of GDP, depending on the methodology used to calculate it. Along with Bulgaria and Romania, this is the highest share in the EU.

According to Prof. Friedrich Schneider from Linz University (Austria), the shadow economy in Lithuania amounted to nearly 21.9 percent of GDP in 2019. Minister of Finance Vilius Šapoka conversely claims that the shadow economy shrank to 14.9 percent, while the Free Market Institute of Lithuania (LLRI)xiii estimates that shadow economic activities constitute 22 percent of the economy as a whole.

According to an LLRI study, as many as 62 percent of the Lithuanian population tolerates the shadow economy, with 46 percent justifying the purchase of illegal alcohol.

Such trends are strongly reinforced by long-term unemployment or the absence of motivation to work. In the event that the financial situation worsens, as many as 53 percent of the population would consider engaging in the shadow economy. Upon losing or quitting their jobs, people look for easy ways to supplement the social benefits they receive.

In such circumstances, engagement in the shadow economy is probably the easiest way to increase one’s income: a person avoids legal employment and legal income from labor in order to avoid losing the unemployment benefit they are “entitled to.”

Long-term benefits strengthen an individual’s inclination to earn in the shadow economy—and when the period of benefit payments comes to an end, the person may remain engaged in the shadow economy out of inertia, due to changes in the style and pace of life that have occurred while benefits were paid, as well as an unwillingness to pay taxes, and so on.

In order to reduce the scope and attractiveness of the shadow economy, it is essential to ensure that people’s motivation to integrate into the labor market and work legally is not stifled by the social policies in place. Ensuring people’s motivation to take up employment is important for the individuals themselves, in terms of their self-esteem and prospects for self-improvement, as well as providing a role model for their children.

It is also important for the state, its economic development, and for the reduction of the scope and tolerance of the shadow economy.

Conclusions

-

The unemployment trap is a relative indicator that represents the level of social benefits received as a share of potential income likely to be received by a jobless individual upon taking up employment. Changes in this indicator depend on the will of public authorities, which can determine both net wages and gross earnings, as well as the amount of unemployment benefits. Individuals with large families who earn minimum wage, are most likely to be caught in the unemployment trap.

-

In contrast to the rest of the euro area, the general trend of the unemployment trap in Lithuania is worsening. During the last year, the unemployment trap increased by one percentage point. In 2019, the unemployment trap in Lithuania stood at 87.8 percent, while the euro area average was 74.5 percent. This means that in Lithuania the financial motivation of an unemployed person to start to work is, on average, 13 percent lower than that of their counterparts across the euro area.

-

In comparison to 2019, a positive trend has been observed during 2020 among those earning minimum monthly wage, the group most sensitive to the unemployment trap. The unemployment trap among this group has dropped by 4 percentage points due to an increase in the minimum wage, while unemployment benefits have not been raised at the same pace.

Unemployment benefits in Lithuania are calculated on the basis of the average monthly insured income received during the thirty months preceding the last month of employment, before the individual registered with the employment service. The unemployment trap will therefore return to its former level after thirty months, provided the minimum monthly wage is not increased.

However, a reduction in the unemployment trap of 4 percentage points is insufficient to positively influence the lowest earners: at 87 percent, it is very high compared to the euro area average.

-

In the period prior to the crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the unemployment rate in Lithuania decreased, while the number of job vacancies increased simultaneously. Companies therefore experienced a lack of workers, particularly in regions where it is hard to find the necessary specialists. This signals not only the failure of the labor market to match the needs of the growing economy and the inadequacy of retraining efforts, but also the lack of workers’ motivation to work.

-

Although some measures aimed at mitigating the COVID-19 will achieve some impact on the economy and help to provide people in the most vulnerable social groups with the income they need in the short term, they also constitute a disincentive to work. The amount of unemployment benefits, and the length of time for which they are paid, have an impact on the unemployment trap. Various exemptions, although not included in the calculation of the unemployment trap, indirectly reduce motivation to reintegrate into the labor market.

-

While child benefits increase a family’s income, they also distort the family’s motivations and the labor market, as well as encourage those on the lowest incomes to stop working. Poland’s example shows that high levels of child benefits do not only incentivize thousands of workers to withdraw from the labor market, but they also fail to achieve their intended objective of increasing the birth rate.

-

When the unemployment trap is high and motivation to find a job is low, engagement in the shadow economy becomes probably the easiest means to increase income and supplement social allowances. Even after benefit payments expire, a person may remain engaged in the shadow economy out of inertia, unwillingness to pay taxes, and for other reasons.

Policies that would help reduce the unemployment trap:

-

Equalize the threshold for untaxed income and the minimum monthly wage, thus enhancing the motivation of the lowest-wage earners to work. This would provide unemployed people with opportunities to fully participate in economic life and the labor market, and to earn higher income in the long run. Budget losses incurred due to lower revenues from the personal income tax would be offset by savings from reduced unemployment benefits.

-

Create conditions for a “signing bonus” by paying the remaining part of the benefit immediately after obtaining employment. The introduction of a signing bonus would help to deal with the issue of the long-term unemployed. Individuals would be motivated to take up employment as quickly as possible, rather than waiting for monthly welfare benefits.

-

Reduce the period of payment of unemployment benefits. This would encourage individuals to seek work more urgently, rather than waiting for the whole period of nine months during which unemployment benefit is paid.

-

Create more flexible forms and conditions of labor that would allow people to supplement their income legally. This would increase worker mobility, making it easier for individuals to find jobs that best match their skills and interests.

-

Abolish the social insurance contributions “floor”, making it easier for workers to take on part-time employment.

ii Data from Lithuania’s Official Statistics Portal: https://osp.stat.gov.lt/informaciniai-pranesimai?articleId=7242270

iii Data from Lithuania’s Official Statistics Portal: https://osp.stat.gov.lt/statistiniu-rodikliu-analize?hash=103cad31-9227-4990-90b0-8991b58af8e7#/

iv Lithuania’s Official Statistics Portal: https://osp.stat.gov.lt/informaciniai-pranesimai?articleId=7188518

v A signing bonus refers to a financial award offered by a business to a prospective employee as an incentive to join the company. The signing bonus may consist of one-time or lump-sum cash payments and/or stock options.

vi Dictionary of Statistical Terms: https://osp.stat.gov.lt/statistikos-terminu-zodynas?popup=true&termId=926

vii Methodology for Calculation of Statistical Indicators by Statistics Lithuania. Note: A simplified formula is used; Statistics Lithuania uses additional data to make its results comparable. https://osp.stat.gov.lt/documents/10180/538622/neto_metodika.pdf

viii Eurostat data: https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=earn_nt_unemtrp&lang=en

ix Survey of Indicators of Monetary Incentives to Work 2019: https://socmin.lrv.lt/uploads/socmin/documents/files/veikla/Trumprastis_METR_20190829_v1_4_clean.pdf

x Child benefits are allocated and paid to parents with respect to every child from birth until the age of eighteen or until the minor is recognized as emancipated or gets married. They are also paid to an emancipated or married minor or persons older than eighteen, provided they are studying in accordance with the general education program, until the age of twenty-one. (This includes persons studying in accordance with the general education program at vocational training institutions or under the vocational training program, until they complete the general education program.) As of January 1, 2020, universal child benefit has been increased from EUR 50.16 to EUR 60.06 EUR per month. Disadvantaged and large families are paid an increased benefit.

xi National Reform Agenda 2020: https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAP/16418d0b8ae511eaa51db668f0092944?positionInSearchResults=0&searchModelUUID=ac428383-c9ad-4359-a6e4-a6054c7a9c9a

xii Civil Development Forum (2019): https://for.org.pl/en/publications/for-reports/report-family-500-program-evaluation-and-proposed-changes

xiii Lithuanian Free Market Institute study: https://www.llri.lt/naujienos/ekonomine-politika/tarptautinis-tyrimas-i-seseline-ekonomika-zmones-stumia-ju-prasta-finansine-situacija/lrinka